Chapter 333 Chronic Diarrhea

Pathophysiology

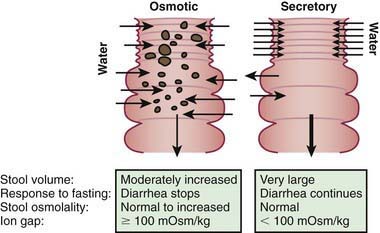

The mechanisms of diarrhea are generally divided into secretory and osmotic, but often diarrhea is the result of both mechanisms. Secretory diarrhea is usually associated with large volumes of watery stools and persists when oral food is withdrawn. Osmotic diarrhea is dependent on oral feeding, and stool volumes are usually not as massive as in secretory diarrhea (Fig. 333-1).

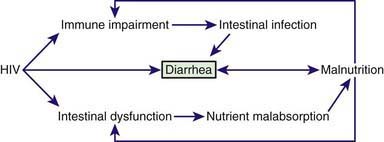

In many children, chronic diarrhea is induced by multiple mechanisms, intersecting each other and often producing a vicious cycle. A paradigm of chronic diarrhea generated by multiple mechanisms is provided by HIV infection, in which immune derangement, enteric infections, nutrient malabsorption, and intestinal damage, together with a direct enteropathogenic role of HIV, trigger and maintain chronic diarrhea (Fig. 333-2).

Etiology

A list of the main causes of chronic diarrhea is shown in Table 333-1.

Table 333-1 INFECTIOUS AND NONINFECTIOUS CAUSES OF CHRONIC DIARRHEA

INFECTIOUS ETIOLOGIES

DIARRHEA ASSOCIATED WITH EXOGENOUS SUBSTANCES

ABNORMAL DIGESTIVE PROCESSES:

NUTRIENT MALABSORPTION

IMMUNE AND INFLAMMATORY

STRUCTURAL DEFECTS

DEFECTS OF ELECTROLYTE AND METABOLITE TRANSPORT

MOTILITY DISORDERS

NEOPLASTIC DISEASES

CHRONIC NONSPECIFIC DIARRHEA

IPEX, immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked syndrome.

In small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, diarrhea may be the result of either a direct interaction between the microorganism and the enterocyte or the consequence of the deconjugation and dehydroxylation of bile salts and the hydroxylation of fatty acids due to an abnormal proliferation of bacteria in the proximal intestine (Chapter 330.4).

A reduction of intestinal absorptive surface is responsible for diarrhea in celiac disease, a permanent gluten intolerance that is sustained by a genetic basis affecting as many as 1/100 normal people, depending on geographic origin. Gliadin induces villous atrophy, leading to a reduction of functional absorptive surface area that is reversible upon implementation of a strict gluten-free diet (Chapter 330.2).

Chronic diarrhea may be the manifestation of maldigestion due to exocrine pancreatic disorders (Chapter 343). In most patients with cystic fibrosis, pancreatic insufficiency results in fat and protein malabsorption. In Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, exocrine pancreatic hypoplasia may be associated with neutropenia, bone changes, and intestinal protein loss. Specific isolated pancreatic enzyme defects result in fat and/or protein malabsorption. Familial pancreatitis, associated with a mutation in the trypsinogen gene, may be associated with pancreatic insufficiency and chronic diarrhea.

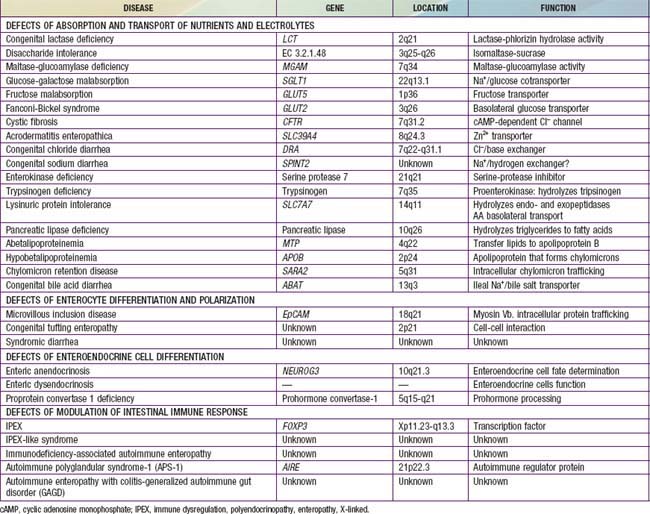

The most severe etiology includes a number of heterogeneous conditions leading to the intractable diarrhea syndrome, which is often the result of a permanent defect in the structure or function of intestine, leading to progressive, often irreversible intestinal failure, requiring parenteral nutrition for survival. The main etiologies of intractable diarrhea include structural enterocyte defects, disorders of intestinal motility, immune-based disorders, short gut, and multiple food intolerance. The genetic and molecular bases of many etiologies of intractable diarrhea have been recently identified (Table 333-2).

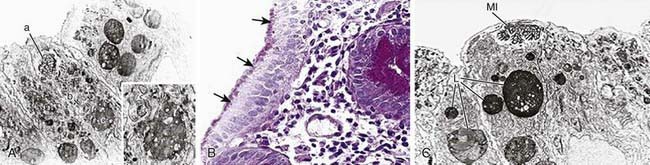

Structural enterocyte defects are due to specific molecular defects responsible for early-onset severe diarrhea. In microvillus inclusion disease, microvilli are sequestered in vacuoles as a consequence of autophagocytosis due to a mutation in myosin that impairs apical protein trafficking leading to aberrant brush border development (Fig. 333-3). Intestinal epithelial dysplasia (or tufting enteropathy) is characterized by disorganization of surface enterocytes with focal crowding and formation of tufts. Abnormal deposition of laminin and heparan sulfate proteoglycan on the basement membrane has been detected in intestinal epithelia. An abnormal intestinal distribution of α2β1 and α6β4 integrins has been implicated in tufting enteropathy. These ubiquitous proteins are involved in cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, and they play a crucial role in cell development and differentiation.

Phenotypic diarrhea, also defined as syndromic diarrhea or tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome, is a rare disease presenting with facial dysmorphism, woolly hair, severe diarrhea, and malabsorption (Fig. 333-4). Half of the patients have liver disease.

Short bowel syndrome (Chapter 330.7) is the single most common etiology of diarrhea and intestinal failure. Many intestinal abnormalities such as stenosis, segmental atresia, and malrotation can require surgical resection. In these conditions the residual intestine may be insufficient to carry on its digestive-absorptive functions. Alternatively, small bowel bacterial overgrowth can cause diarrhea, such as in the blind loop syndrome.

Evaluation of Patients

Because of the wide spectrum of the etiologies, the medical approach should be based on diagnostic algorithms that begin with the age of the child, evaluate the weight pattern, and then consider clinical and epidemiologic factors, always taking into account the results of microbiologic investigations. The etiology of chronic diarrhea shows an age-related pattern, and an early onset might suggest a congenital and severe condition. In later infancy and up to 2 yr of age, infections and allergies are more common, whereas inflammatory diseases are more common in older children and adolescents. Celiac disease on the one hand, and chronic nonspecific diarrhea on the other, should always be considered independent of age owing to their relatively high frequency (Table 333-3).

Table 333-3 MAIN CAUSES OF CHRONIC DIARRHEA ACCORDING TO THE AGE OF ONSET*

| 0-30 DAYS | 1-24 MONTHS | 2-18 YEARS |

|---|---|---|

| Microvillus inclusion disease | Apple juice and pear nectar | Apple juice or pear nectar |

| Autoimmune enteropathy | Antibiotic-associated Clostridium difficile colitis | |

| Intestinal infection | Intestinal infection | |

| Congenital short bowel syndrome | Short gut | |

| Food allergy | Food allergy | Lactose intolerance |

| Functional diarrhea† | Irritable bowel syndrome‡ | |

| Celiac disease | Celiac disease | |

| Hirschsprung’s disease | Cystic fibrosis | |

| Malrotation with partial blockage | Post-gastroenteritis diarrhea | Post-gastroenteritis diarrhea |

| Neonatal lymphangectasia | ||

| Tufting enteropathy | ||

| Primary bile-salt malabsorption | ||

| Intestinal pseudo-obstruction | Intestinal pseudo-obstruction |

* In addition to all the diseases listed in Table 333-2.

Specific clues in the family and personal history may provide useful indications, suggesting a congenital, allergic or inflammatory etiology. A previous episode of acute gastroenteritis suggests postenteritis syndrome, whereas the association of diarrhea with specific foods can indicate a food allergy. A history of polyhydramnios is consistent with congenital chloride or sodium diarrhea or, conversely, cystic fibrosis. The presence of eczema or asthma is associated with an allergic disorder, whereas specific extraintestinal manifestations (e.g., arthritis, diabetes, thrombocytopenia) might suggest an autoimmune disease. Specific skin lesions can suggest acrodermatitis enteropathica. Typical facial abnormalities and woolly hair are associated with phenotypic diarrhea (see Fig. 333-4).

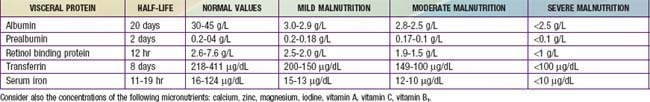

Biochemical markers assist in grading malnutrition (Table 333-4). The half -life of serum proteins can differentiate between short-term and long-term malnutrition. Assessment of body composition may be performed by measuring mid-arm circumference and triceps skinfold thickness or, more accurately, by bioelectrical impedance analysis or dual emission x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans.

Table 333-4 DEGREE OF MALNUTRITION AS ESTIMATED BY VISCERAL PROTEIN CONCENTRATIONS IN CHILDREN WITH CHRONIC DIARRHEA

Diagnosis of functional diarrhea is based on pure clinical grounds using established age-related criteria (see Table 333-3). Conversely, a child with persistent diarrhea and suspected malabsorption might be inappropriately “treated” with a diluted hypocaloric diet in an effort to reduce the diarrhea, and persistent diarrhea may be an indirect consequence of ongoing malnutrition. One such example of this vicious cycle is exocrine pancreatic insufficiency due to protein calorie malnutrition.

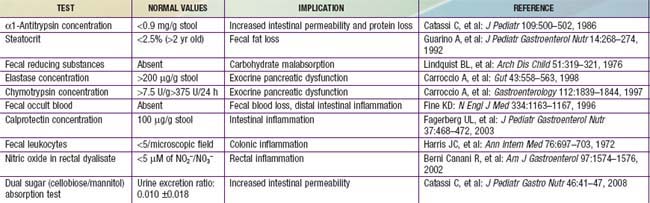

Noninvasive assessment of digestive-absorptive functions and of intestinal inflammation plays a key role in the diagnostic work-up (Table 333-5).

Table 333-5 NONINVASIVE TESTS FOR INTESTINAL AND PANCREATIC DIGESTIVE-ABSORPTIVE FUNCTIONS AND INTESTINAL INFLAMMATION

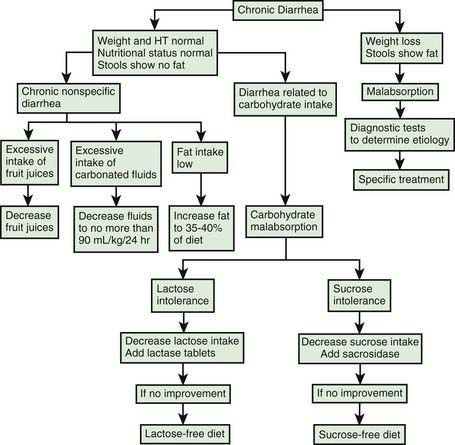

Once infectious agents have been excluded and nutritional assessment performed, a stepwise approach to the child with chronic diarrhea may be applied. The main etiologies of chronic diarrhea should be investigated based on the features of diarrhea and their predominant or selective intestinal dysfunction. A step-by-step diagnostic approach is important to minimize the unnecessary use of invasive procedures and overall costs, while optimizing the yield of the diagnostic work-up (Table 333-6, Fig. 333-5).

Table 333-6 STEPWISE DIAGNOSTIC WORK-UP FOR CHILDREN WITH CHRONIC DIARRHEA

STEP 1

STEP 2

STEP 3

PAS, periodic acid–Schiff; 75SeHCAT, 75Se–homocholic acid–taurine.

Treatment

Micronutrient and vitamin supplementation are part of nutritional rehabilitation and prevent further problems, especially in malnourished children from developing countries. Zinc supplementation is an important factor in both prevention and therapy of chronic diarrhea, because it promotes ion absorption, restores epithelial proliferation, and stimulates immune response. Nutritional rehabilitation has a general beneficial effect on the patient’s overall condition, intestinal function, and immune response and can break the vicious circle shown in Figure 333-2.

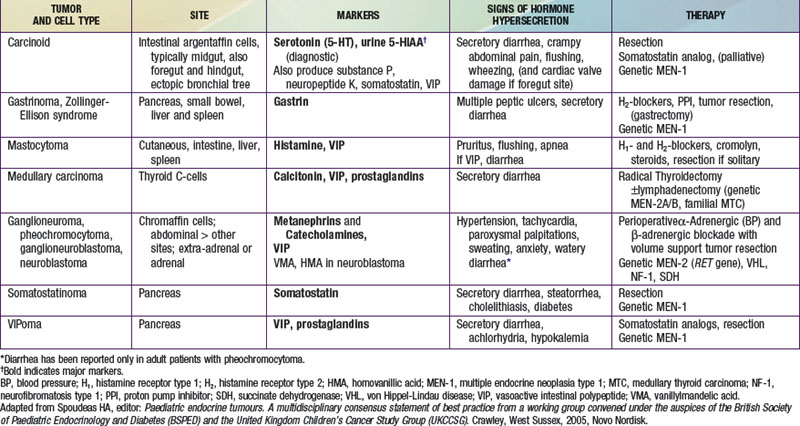

333.1 Diarrhea from Neuroendocrine Tumors

Helen Spoudeas and David Branski

Rare tumors of the neuroendocrine cells of the gastroenteropancreatic axis and adrenal and extra-adrenal sites derive from the APUD system. They are characterized by an excessive production of one or several peptides, which when released into the circulation exert their endocrine effects and can be measured by radioimmunologic methods (in the plasma or as their urinary metabolites) and hence act as tumor markers. In clinically functioning tumors, the hypersecretion causes a recognizable syndrome that can include watery diarrhea. Though rare, neuroendocrine tumor (NET) should be considered a potential cause in patients with a particularly severe or chronic course (resulting in electrolyte and fluid depletion), associated flushing or palpitations, or a positive family history of multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN-1 or MEN-2) syndromes ![]() (see Table 333-7 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com).

(see Table 333-7 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com).

Berginer VM, Gross B, Morad K, et al. Chronic diarrhea and juvenile cataracts: Think cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis and treat. Pediatrics. 2009;123:143-147.

Berni Canani R, Cirillo P, Mallardo G, et al. Effects of HIV-1 Tat protein on ion secretion and on cell proliferation in human intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:368-376.

Branski D, Lerner A, Lebenthal E. Chronic diarrhea and malabsorption. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1996;43:307-331.

Canani RB, Ruotolo S, Auricchio L, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the atopy patch test in children with food allergy-related gastrointestinal symptoms. Allergy. 2007;62:738-743.

Cohen MB. Clostridium difficile infections: emerging epidemiology and new treatments. J Pediatric Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:S63-S65.

Goulet O, Ruemmele F. Causes and management of intestinal failure in children. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:S16-S28.

Goulet O, Vinson C, Roquelaure B, et al. Syndromic (phenotypic) diarrhea in early infancy. Orphanet J Rare Disease. 2008;3:1-6.

Guarino A, De Marco G, for the Italian National Network for Pediatric Intestinal Failure. Natural history of intestinal failure, investigated through a network-based approach. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:136-141.

Guarino A, Bruzzese E, De Marco G, et al. Management of gastrointestinal disorders in children with HIV infection. Pediatr Drugs. 2004;6:347-362.

Khan S, Orenstein SR. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37:333-348.

Hyman PE, Milla PJ, Benninga MA, et al. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: neonate/toddler. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1519-1526.

Morroni M, Cangiotti AM, Guarino A, et al. Unusual ultrastructural features in microvillous inclusion disease: a report of two cases. Virchows Archiv. 2006;448:805-810.

Rasquin A, Di Lorenzo C, Forbes D, et al. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1527-1537.

Ruemmele FM. Chronic enteropathy: molecular basis. Nestle Nutr Workshop. 2007;59:73-85.

Salvia G, Guarino A, Terrin G, et al. Neonatal onset intestinal failure: an Italian multicenter study. J Pediatr. 2008;153:674-676.

Saps M, Pensabene L, Di Martino L, et al. Post-infectious functional gastrointestinal disorders in children. J Pediatr. 2008;152:812-816.

Sherman PM, Mitchell DJ, Cutz E. Neonatal enteropathies: defining the causes of protracted diarrhea of infancy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:16-26.

Thomson M, Fritscher-Ravens A, Mylonaki M, et al. Wireless capsule endoscopy in children: a study to assess diagnostic yield in small bowel disease in paediatric patients. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:192-197.