Choroid plexus neoplasms

CHOROID PLEXUS NEOPLASMS

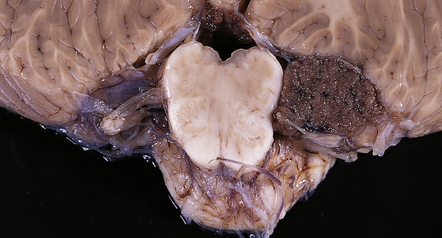

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

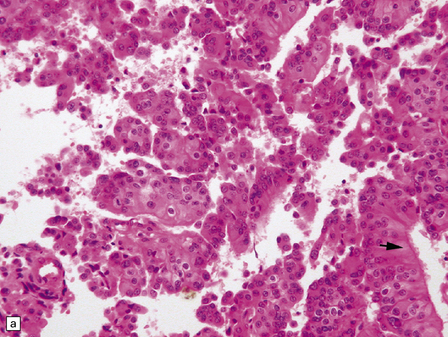

CPPs are well-circumscribed neoplasms with a stippled surface that reflects their papillary structure (Fig. 40.1). In contrast, CPCs tend to invade local structures. Both types of neoplasm can be highly vascular, and CPCs frequently contain foci of hemorrhage (Fig. 40.2).

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

CPPs resemble normal CP, being characterized by a columnar epithelium that rests on a delicate fibrovascular network and forms multiple papillary projections (Figs 40.3, 40.4). However, CPPs can be distinguished from CP because they demonstrate minor atypical cytologic features, such as:

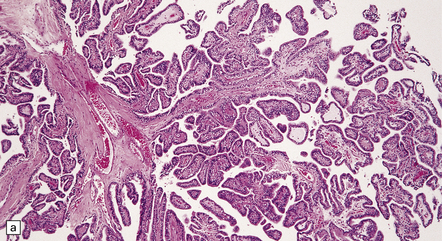

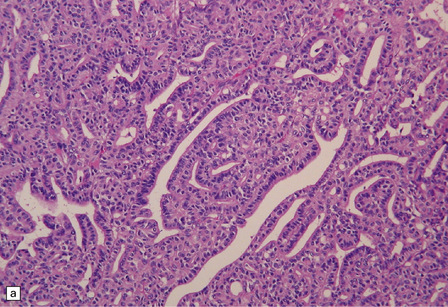

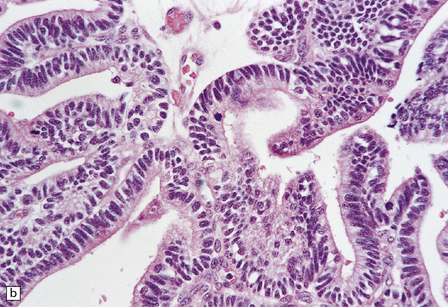

40.3 CPP.

(a) In many areas, an obvious papillary architecture is found. A more complex pattern may be present in atypical CPPs (b) but this and superficial invasion of the stroma (arrow) do not warrant a diagnosis of CPC.

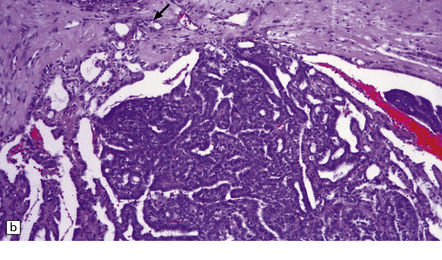

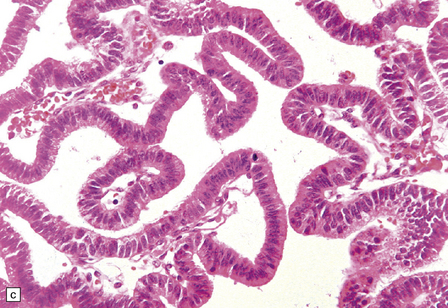

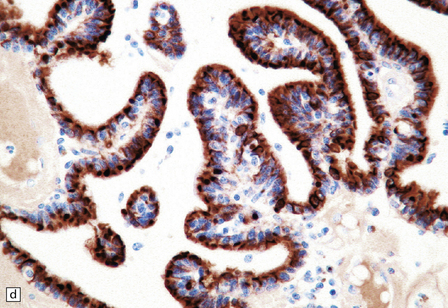

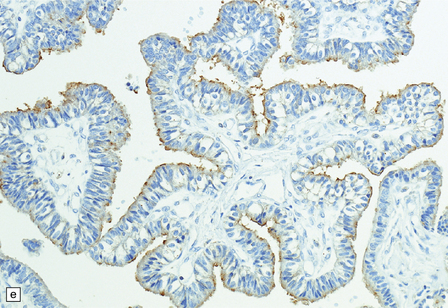

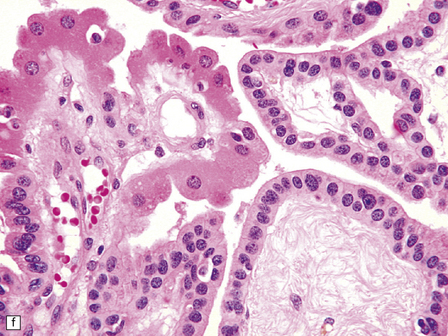

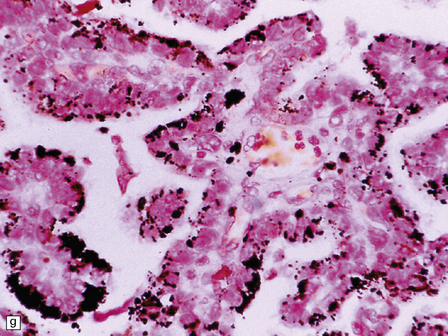

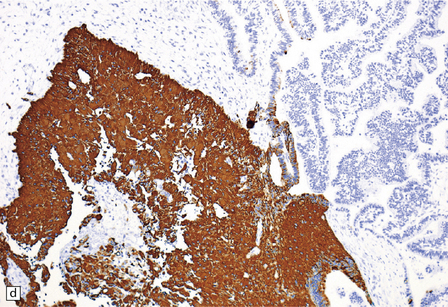

40.4 CPP.

(a) A layer of cuboidal or columnar cells rests on a fibrovascular stroma. (b,c) In addition to architectural abnormalities, mild cytological atypia and occasional mitoses distinguish the CPP from CP. (d) Immunoreactivity for cytokeratins is a feature of CP tumors. (e) Kir7.1 antibodies label the membrane of epithelial cells in CP neoplasms. (f) Rare CPPs contain oncocytic cells, or (g) melanin.

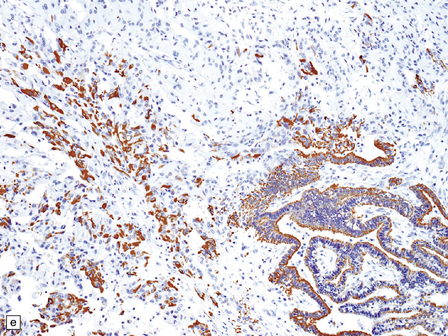

Common histologic features found in both CPPs and CP include dystrophic calcification and xanthomatous change. Glial differentiation can very occasionally be found in CPPs, and focal immunoreactivity for GFAP is common. Sometimes, cilia are observed on the surface of epithelial cells in CP neoplasms. Uncommon histologic features in CPPs are glandular metaplasia, oncocytic change (Fig. 40.4f), melanin pigment (Fig. 40.4g), chondroid metaplasia, and osseous metaplasia. Histological atypia may be more advanced in some CPPs (Fig. 40.5), and can progressively worsen in recurrent neoplasms. The atypical CPP is defined as a CPP with: increased frequency of mitotic figures (≥ 2/10 high-powered fields). The following features are not required for diagnosis, but may be present:

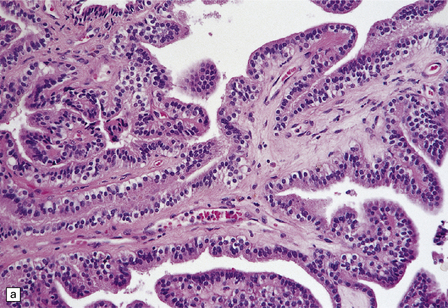

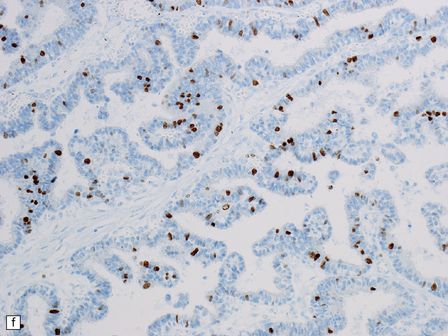

40.5 Atypical CPP.

An atypical CPP may have a more complex architectural pattern than a classic CPP, demonstrating focal loss of papillary structure (a), but the diagnosis is made by detecting increased mitotic activity (b). Glial differentiation is a feature of some CPPs (c), this atypical CPP containing a focus of astrocytic cells that demonstrated immunoreactivities for both GFAP (d) and cytokeratins (e). Ki-67 immunolabeling is increased in atypical CPPs (f), in parallel with the mitotic count.

complex architectural features, such as a cribriform pattern of anastamosizing papillae, or areas where cells form patternless sheets

complex architectural features, such as a cribriform pattern of anastamosizing papillae, or areas where cells form patternless sheets

foci of increased cellular pleomorphism and nuclear hyperchromasia

foci of increased cellular pleomorphism and nuclear hyperchromasia

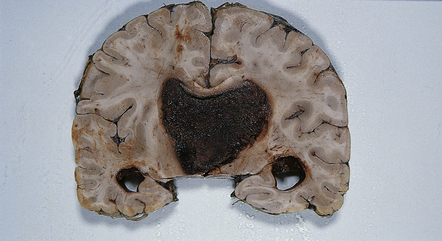

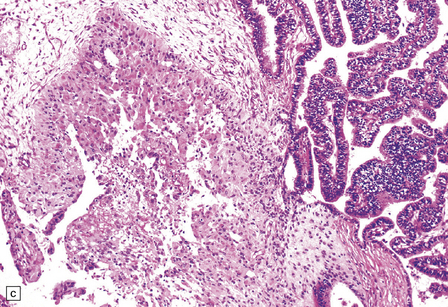

CPCs are characterized by marked architectural and cytologic atypia. They may invade adjacent brain, have a high mitotic index, and contain areas of necrosis (Fig. 40.6). Poorly differentiated CPCs may retain only small foci with a papillary architecture.

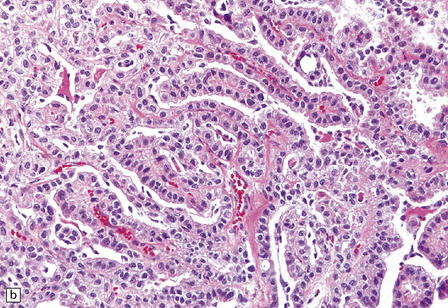

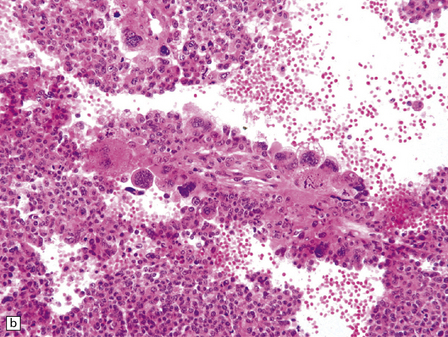

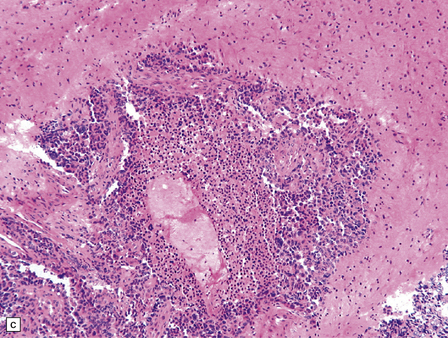

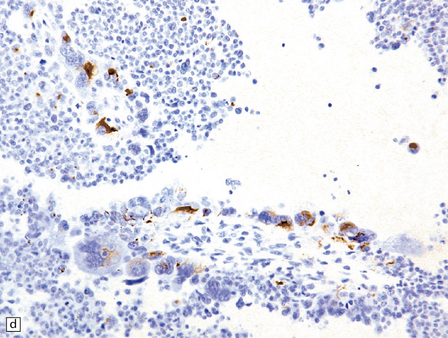

40.6 CPC.

This CPC shows marked architectural and cytological abnormalities, including invasion of adjacent brain, loss of papillary architecture, foci of necrosis, nuclear pleomorphism and a high mitotic count (a), (b), and (c). Note the focal formation of cilia (arrowhead) in (a). Immunoreactivity for cytokeratins is often restricted in CPC (d).

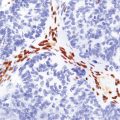

Immunohistochemistry reveals that most cells in CPPs label with antibodies to cytokeratins (Fig. 40.4d), S-100 and vimentin. CPPs also show focal GFAP immunoreactivity. Antibodies to transthyretin (prealbumin) label CP neoplasms, but this reactivity is not specific. However, antibodies to Kir7.1 (Fig. 40.4e), an inwardly rectifying potassium channel, appear almost entirely specific for CP neoplasms.

REFERENCES

Dang, L., Fan, X., Chaudhry, A., et al. Notch3 signaling initiates choroid plexus tumor formation. Oncogene.. 2006;25:487–491.

Furness, P.N., Lowe, J., Tarrant, G.S. Subepithelial basement membrane deposition and intermediate filament expression in choroid plexus neoplasms and ependymomas. Histopathology.. 1990;16:251–255.

Gozali, A.E., Britt, B., Shane, L., et al. Choroid plexus tumors; management, outcome, and association with the Li-Fraumeni syndrome: The Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA) experience, 1991–2010. Pediatr Blood Cancer.. 2011. [Epub:21990040].

Hasselblatt, M., Böhm, C., Tatenhorst, L., et al. Identification of novel diagnostic markers for choroid plexus tumors: a microarray-based approach. Am J Surg Pathol.. 2006;30:66–74.

Ho, D.M., Wong, T.T., Liu, H.C. Choroid plexus tumors in childhood. Histopathologic study and clinico-pathological correlation. Childs Nerv Syst.. 1991;7:437–441.

Jeibmann, A., Hasselblatt, M., Gerss, J., et al. Prognostic implications of atypical histologic features in choroid plexus papilloma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol.. 2006;65:1069–1073.

Judkins, A.R., Burger, P.C., Hamilton, R.L., et al. INI1 protein expression distinguishes atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor from choroid plexus carcinoma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol.. 2005;64:391–397.

Kepes, J.J., Collins, J. Choroid plexus epithelium (normal and neoplastic) expresses synaptophysin. A potentially useful aid in differentiating carcinoma of the choroid plexus from metastatic papillary carcinomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:398–401.

Krutilkova, V., Trkova, M., Fleitz, J., et al. Identification of five new families strengthens the link between childhood choroid plexus carcinoma and germline TP53 mutations. Eur J Cancer.. 2005;41:1597–1603.

Levy, M.L., Goldfarb, A., Hyder, D.J., et al. Choroid plexus tumors in children: significance of stromal invasion. Neurosurgery.. 2001;48:303–309.

Newbould, M.J., Kelsey, A.M., Arango, J.C., et al. The choroid plexus carcinomas of childhood: histopathology, immunocytochemistry and clinicopathological correlations. Histopathology.. 1995;26:137–143.

Paulus, W., Jänisch, W. Clinicopathologic correlations in epithelial choroid plexus neoplasms: a study of 52 cases. Acta Neuropathol.. 1990;80:635–641.

Rickert, C.H., Paulus, W. Tumors of the choroid plexus. Microsc Res Tech.. 2001;52:104–111.

Sharma, R., Rout, D., Gupta, A.K., et al. Choroid plexus papillomas. Br J Neurosurg.. 1994;8:169–177.

Tabori, U., Shlien, A., Baskin, B., et al. TP53 alterations determine clinical subgroups and survival of patients with choroid plexus tumors. J Clin Oncol.. 2010;28:1995–2001.

Wolff, J.E., Sajedi, M., Brant, R., et al. Choroid plexus tumours. Br J Cancer.. 2002;87:1086–1091.