Childbirth Preparation and Nonpharmacologic Analgesia

Marie E. Minnich MD, MMM, MBA, CPE

Chapter Outline

Pregnant women and their support person(s) obtain information about childbirth and analgesia from many sources. The more traditional sources of information include obstetricians, childbirth preparation classes, lay periodicals, books and pamphlets, and experiences of family and friends. Currently, the Internet has become the primary source of information for many patients. Many health care organizations provide patient access to community health libraries on site that include Internet access and librarian support to facilitate information searches. Anesthesia providers should be familiar with the information that patients in the local area are using for decision-making, because this information influences their birth experiences. Knowledge of the information and biases held by patients helps anesthesia providers in their interactions with pregnant women.

Prepared childbirth training provides undeniable benefits to the pregnant woman and her support person. However, prepared childbirth training should not be equated with nonpharmacologic analgesia.1 Some childbirth preparation instructors discourage the use of medications during labor and delivery, whereas others make a nonbiased presentation of the advantages and disadvantages of various analgesic techniques. The information contained in this chapter provides a basis for informed discussion of pain relief options among patients, nurses, obstetricians, and anesthesia providers.

Pain Perception

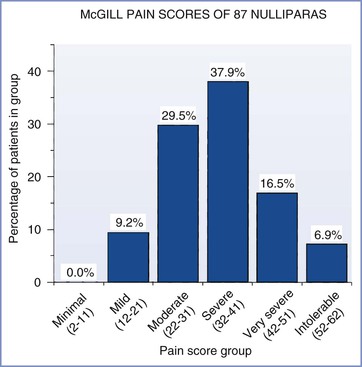

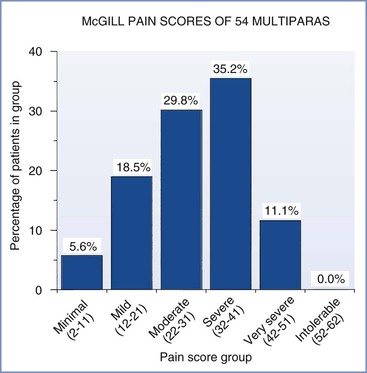

Anesthesia providers are indebted to John Bonica and Ronald Melzack for their studies of the pain of childbirth. Investigators have used sophisticated questionnaires2,3 and visual analog scales4 to evaluate the maternal perception of pain during parturition. Melzack et al.5,6 developed the McGill Pain Questionnaire to measure the intensity of labor pain for various conditions. They noted that labor pain is one of the most intense types of pain among those studied (see Figure 20-2). Parous women had lower pain scores than nulliparous women, but responses varied widely (Figures 21-1 and 21-2). Prepared childbirth training resulted in a modest decrease in the average pain score among nulliparous women, but it clearly did not eliminate pain in these women.5,6

Childbirth Preparation

History

The history of modern childbirth preparation began in the first half of the 20th century; however, it is important to review earlier changes in obstetric practice to understand the perceived need for a new approach. Before the mid-19th century, childbirth occurred at home in the company of family and friends. The specialty of obstetrics developed in an effort to decrease maternal mortality. Interventions initially developed for the management of complications became accepted and practiced as routine obstetric care. Physicians first administered anesthesia for childbirth during this period. The 1848 meeting of the American Medical Association included reports of the use of ether and chloroform in approximately 2000 obstetric cases.7 The combination of morphine and scopolamine (i.e., twilight sleep) was introduced in the early 20th century. These techniques were widely used, and influential women demanded that they be made available to all parturients.8 Together, these developments moved childbirth from the home and family unit to the hospital environment.9 Despite their desire for analgesia/anesthesia for labor and delivery, women began to resent the fact that they were not active participants in childbirth.

Beck et al.10 wrote a detailed history of childbirth preparation. Dick-Read11,12 reported the earliest method in his books, Natural Childbirth and Childbirth Without Fear. In his original publication, he asserted his belief that childbirth was not inherently painful. He opined that the pain of childbirth results from a “fear-tension-pain syndrome.” He believed—and taught—that antepartum instruction about muscle relaxation and elimination of fear would prevent labor pain. He later established antenatal classes that included groups of mothers and fathers. Some readers incorrectly concluded that he advocated a return to primitive obstetrics, but this was not the case. Review of his practice reveals that he used the available obstetric techniques—including analgesia, anesthesia, episiotomy, forceps, and abdominal delivery—as appropriate for the individual patient. However, he cautioned against the routine use of these procedures, and he encouraged active participation of mothers in the delivery of their infants. Unfortunately, he did not use the scientific method to validate his beliefs.

Although Dick-Read was the earliest proponent of natural childbirth, it was Fernand Lamaze13 who introduced the Western world to psychoprophylaxis. His publications were based on techniques that he observed while traveling in Russia. Although his theories ostensibly were translations of teachings later published in the West by Velvovsky et al.,14 they contained substantial differences and modifications. The “Lamaze method” became popular in the United States after Marjorie Karmel15 wrote about her childbirth experience under the care of Dr. Lamaze. Within a year of the publication of her book Thank You, Dr. Lamaze: A Mother’s Experiences in Painless Childbirth, the American Society for Psychoprophylaxis in Obstetrics was born. Lamaze and Karmel published their experience at a time when organizations such as the International Childbirth Education Association and the La Leche League were formed.16 These organizations actively and aggressively encouraged a renewed emphasis on family-centered maternity care, and society was ripe for the ideas and theories promoted by these organizations. Women were ready to actively participate in childbirth and to have input in decisions about obstetric and anesthetic interventions. Childbirth preparation methods were taught and used extensively, despite a lack of scientific validation of their efficacy.

In 1975, Leboyer17 described a modification of natural childbirth in his book Birth Without Violence. He advocated childbirth in a dark, quiet room; gentle massage of the newborn without routine suctioning; and a warm bath soon after birth. He opined that these maneuvers result in a less shocking first-separation experience and a healthier, happier infancy and childhood. Although there are few controlled studies of this method, published observations do not support his claim of superiority.18,19

Physicians were the initial advocates of the various natural childbirth methods. Obstetricians had become increasingly aware that analgesic and anesthetic techniques were not harmless, and they supported the use of natural childbirth methods.10 Subsequently, natural childbirth, like the methods of obstetric analgesia introduced earlier in the century, was actively promoted by lay groups rather than physicians.20 Lay publications, national advocacy groups, and formal instruction of patients accounted for the greater interest in psychoprophylaxis and other techniques associated with natural childbirth.

Goals and Advantages

The major goals of childbirth education that were initially promoted by Dick-Read are taught with little modification in formal childbirth preparation classes today. Most current classes credit Lamaze with the major components of childbirth preparation, even though Dick-Read was the first to promote patient education, relaxation training, breathing exercises, and paternal participation.10 Box 21-1 describes the goals of current childbirth preparation classes. In addition, some instructors and training manuals claim other benefits of childbirth preparation (Box 21-2). Reviews by Beck and Hall21 and Lindell22 concluded that much of the research on the efficacy of childbirth education does not meet the fundamental requirements of the scientific method. Despite these shortcomings, childbirth preparation classes are widely available and attended.

Socioeconomic disparities exist in childbirth education class attendance.23 In addition, the effect of childbirth education on attitude and childbirth experience depends in part on the social class to which the mother belongs. Most investigators have found that childbirth classes have a positive effect on the attitudes of both parents in all social classes, but this effect is more pronounced among “working class”24 and indigent women25; this latter finding probably reflects the greater availability and use of other educational materials by middle- and upper-class women. Childbirth classes often are the only—or at least the primary—source of information for working class and indigent women.

Limitations

Limitations of the widespread application of psychoprophylaxis and other childbirth preparation methods remain. Proponents assume that these techniques are easily used during labor and delivery; however, Copstick et al.26 concluded that this assumption is not valid. They found that patients were able to use the coping techniques in the early first stage of labor but that the successful use of the coping skills became less and less common as labor progressed. By the onset of the second stage, less than one third of mothers were able to use any of the breathing or postural techniques taught during their childbirth classes.26 The method of preparation influences the ability of the pregnant woman to use the breathing and relaxation techniques. Bernardini et al.27 observed that self-taught pregnant women are less likely to practice the techniques during the prenatal period or to use the techniques during labor.

Childbirth preparation classes may create false expectations. If a woman does not enjoy the “normal” delivery discussed during classes, she may experience a sense of failure or inferiority. Both Stewart28 and Guzman Sanchez et al.29 have discussed the psychological reactions of women who were unable to use psychoprophylaxis successfully during labor and delivery. In addition, several women have written about their disappointment with the dogmatic approach of their childbirth instructors; these women described instructors who rigidly defined the “correct” way to have a “proper” birth experience.30,31

Effects on Labor Pain and Use of Analgesics

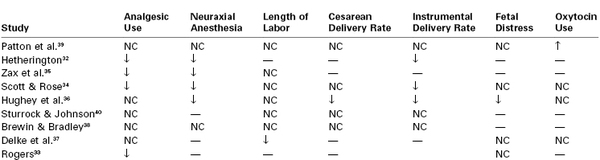

Little scientific evidence supports the efficacy of childbirth preparation in mitigating labor pain. Psychology, nursing, obstetric, anesthesia, and lay journals provide extensive discussions of childbirth preparation, but most articles describe uncontrolled clinical experiences. Outcome studies often do not include a group of women who were randomly assigned to an untreated or a placebo-control group, and statistical analysis is often incomplete. Despite these shortcomings, supporters of childbirth preparation assume that it offers benefits for mother and child. Table 21-1 summarizes a few of the studies of Lamaze and other childbirth preparation techniques and their association with labor outcomes. The findings are not consistent. Some researchers have reported a decreased use of analgesics32–35 or regional anesthesia,32–36 shorter labor,37 reduced performance of instrumental32,34,36 and cesarean delivery,36 and a lower incidence of nonreassuring fetal status,36 whereas others have reported no change in the use of analgesics36–40 or neuraxial analgesia,38,39 length of labor,34–36,38–41 performance of instrumental38–40 and cesarean delivery,34,38–40 or incidence of nonreassuring fetal status.33,34,37,39 These diverse findings may reflect different patient populations, poor study design, or researcher bias.

TABLE 21-1

Effects of Childbirth Preparation

NC, No change; ↑, increased; ↓, decreased; —, not studied/reported.

To elucidate the effect of the coping techniques taught in childbirth classes, several investigators have attempted to quantify changes in pain threshold, pain perception, anxiety levels, and physiologic responses to standardized stimuli. Several studies have evaluated nonpregnant and nulliparous women in laboratory settings,42–45 and another study evaluated pregnant women in the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum periods.46 Conclusions varied according to the stimuli applied, the coping techniques studied, and the parameters analyzed. Together, these studies suggest that practicing these techniques facilitates their efficacy and that newer cognitive techniques (e.g., systematic desensitization, sensory transformation) may be more effective than traditional Lamaze techniques of varied breathing patterns and relaxation. Further studies may help refine childbirth preparation to maximize the positive psychophysiologic effects.

Nonpharmacologic Analgesic Techniques

Nonpharmacologic analgesic techniques range from those that require minimal specialized equipment and training and are available to all patients to those that are offered only by institutions with the necessary equipment and personnel trained in their use (Box 21-3). Many studies have assessed nonpharmacologic methods of labor analgesia; however, most published studies have not fulfilled the requirements of the scientific method.47–49 Several comprehensive reviews of alternative therapies for pain management during labor have been published,47–49 providing a foundation for discussion with patients and obstetric providers. However, clinical evidence is insufficient to form the basis for an in-depth discussion of some of the more recent therapeutic suggestions, such as music therapy, aromatherapy, and chiropractic. These analgesic techniques may provide intangible benefits that are not easily documented by a rigorous scientific method. Parturients may consider these benefits an integral and important part of their labor experience.

Continuous Labor Support

Some techniques that require minimum equipment and specialized training are taught as integral components of childbirth preparation classes. Continuous support during labor is essential to the process of a satisfying childbirth experience; typically, the parturient’s husband or friend provides this support.50,51 This support appears most helpful for the parturient who lives in a stable family unit. At least one study noted that husband participation was associated with decreased maternal anxiety and medication requirements.51 Others have found that emotional support provided by unfamiliar trained individuals (e.g., doulas) also has a positive effect.52–55 Several studies have evaluated the benefits of emotional support provided by doulas or other unrelated individuals on the length of labor,52,53,55 oxytocin use,53 requirements for analgesia and/or anesthesia,52,53 incidence of operative delivery,53 and maternal morbidity.53,54 These studies all suggested that a patient’s sense of isolation adversely affects her perception of labor. Further, the companionship of another woman who is not part of the medical establishment may reduce a parturient’s anxiety more effectively than the companionship provided by her husband. In one study, women randomly assigned to receive intrapartum support from a friend or female relative (who was chosen by the parturient and trained as a doula) were more likely to have positive feelings about their delivery and had a higher rate of breast-feeding 6 to 8 weeks after delivery than women who were randomly assigned to receive usual care.41

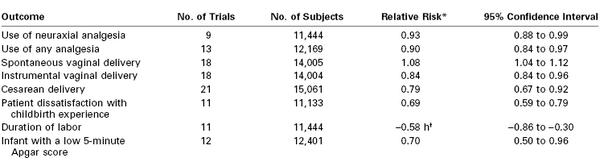

A meta-analysis evaluated results from 21 studies that included more than 15,000 women who were randomly assigned to receive either continuous childbirth support or usual care (Table 21-2).56 The pooled data suggested that women who received one-on-one support during labor were less likely to use neuraxial analgesia or receive any type of analgesia, were more likely to have a spontaneous vaginal delivery, and reported less dissatisfaction with the childbirth experience.56 In addition, the mean duration of labor was slightly shorter (approximately 35 minutes) in the women who received continuous support during labor. There were no differences in neonatal outcome.

TABLE 21-2

Systematic Review: Continuous Labor Support versus Usual Care

* For women who received continuous support.

† Weighted mean difference.

Data are summarized from Hodnett ED, Gates S, Hofmeyr GJ, et al. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; (2):CD003766.

These results are fascinating and have important implications for obstetric care. The patient populations studied represent special situations, and the results may not be reproduced in all populations. For example, a large randomized, controlled trial in a North American hospital (in which intrapartum medical intervention is routine) found no differences in the rate of cesarean delivery or other labor outcomes between women randomly assigned to receive continuous labor support from a specially trained nurse and women who received usual care.57 In general, results from trials in North America do not appear as striking as those from Europe or Africa.47 The aforementioned systematic review of continuous labor support suggested that benefits were greater when the support person was not a member of the hospital staff.56 Further studies should compare different models of continuous childbirth support and should include outcomes such as cost analysis.56 Meanwhile, the preponderance of evidence suggests that all parturients should have access to emotional support, whether it is provided by the husband, a family member, a labor companion (e.g., doula), or professional hospital staff.

Touch and Massage

Various touch and massage techniques are discussed with women and their support persons during childbirth preparation classes. These techniques include effleurage, counterpressure to alleviate back discomfort, light stroking, and merely a reassuring pat.47 There has been minimal scientific study of the effects of touch and massage on labor progress and outcome58–60; nonetheless, touch and massage provide a comfort that is appreciated by women during labor. These measures may be used by the parturient, her support person, or the professional staff members providing intrapartum care. The techniques are easily discontinued if the parturient desires. In some cases, touch and massage may reduce discomfort. More often, touch and massage transmit a sense of caring, which fosters a sense of security and well-being.

Therapeutic Use of Heat and Cold

Another simple technique for alleviating labor pain is the therapeutic use of temperature (hot or cold) applied to various regions of the body. Warm compresses may be placed on localized areas, or a warm blanket may cover the entire body. Alternatively, ice packs may be placed on the low back or perineum to decrease pain perception. The therapeutic use of heat and cold during labor has not been studied in a rigorously scientific manner. The use of superficial heat and cold for comfort is widespread (if not completely understood), and it has no discernible risk to the mother or the fetus.47 Cold and heat should not be applied to anesthetized skin.

Hydrotherapy

Hydrotherapy may involve a simple shower or tub bath or may include the use of a whirlpool or large tub specially equipped for pregnant women. Purported benefits of hydrotherapy include decreased anxiety and pain and greater uterine contraction efficiency.47 Results of randomized, controlled trials comparing water baths with usual care are inconsistent. For example, some studies have found no difference between groups in the use of pharmacologic analgesia,61,62 whereas others have demonstrated a lower use in the water bath group.63,64 A meta-analysis of eight published trials involving almost 3000 women concluded that there was a reduction in the use of neuraxial analgesia in women randomly assigned to water immersion compared with control subjects (odds ratio [OR], 0.84; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.71 to 0.99).65 There were no differences in the rate of operative delivery or neonatal outcome, including infection. In summary, bathing, showering, and other hydrotherapy maneuvers are comfort measures with little risk to the mother and the infant, provided that appropriate monitoring continues during the immersion in water that is kept at body temperature.

Vertical Position

Several investigators have studied the effects of various positions on pain perception and labor outcome. These positions are broadly categorized as vertical (e.g., sitting, standing, walking, squatting) or horizontal (e.g., supine, lateral). A systematic review summarized the results from 13 controlled trials of maternal posture during the first stage of labor.66 In 7 trials in which women served as their own controls, women reported less pain in the standing and sitting positions than in the supine position. Six other trials randomly assigned women to either an experimental group who were encouraged to remain upright or a control group who remained supine or on their side. Women in the upright groups experienced less pain or no difference in pain when compared with the recumbent groups. A recent Cochrane review of 21 studies also found that walking and the upright position are associated with shorter labor without the need for interventions.67

Ambulation in the presence of neuraxial analgesia does not appear to influence the outcome of labor.68–70 In a prospective, randomized study, Bloom et al.68 noted that walking did not shorten the duration of the first stage of labor or reduce the requirement for oxytocin augmentation, the use of analgesia, or the requirement for operative delivery. They concluded that “walking neither enhanced nor impaired active labor and was not harmful to the mothers or their infants.”68

A number of studies have assessed maternal position during the second stage of labor. There is renewed interest in the squatting or modified squatting position and its greater comfort for some women during childbirth. Most authorities have noted that Western women have insufficient muscular strength and stamina to maintain an unsupported squatting position for any length of time.71–73 Squatting does not appear to alter pelvic dimensions.74 Gardosi et al.71 designed and studied a birth cushion that allows a modified, supported squat, which resulted in a higher incidence of spontaneous vaginal delivery and a lower incidence of perineal tears. Others have yet to substantiate the results of this trial.

Some studies have evaluated the use of a birth chair to facilitate delivery in the sitting position.75–77 These studies noted no difference in length of the second stage of labor, mode of delivery, occurrence of perineal trauma, or Apgar scores in parturients who used a birth chair compared with those who did not. Of concern, two studies reported greater intrapartum blood loss and a higher incidence of postpartum hemorrhage in the birth-chair group.76,77

A systematic review of studies of maternal position in the second stage of labor in women without epidural analgesia concluded that currently published trials are generally of poor quality.78 Tentative results suggest that less severe pain and a lower rate of perineal trauma may be associated with giving birth in the upright position; however, blood loss may be greater. Although the investigators concluded that further study is required, many obstetricians and nurses believe that ambulation and the upright posture result in a shorter labor that requires less analgesia. An alternative explanation for the observation that ambulatory parturients appear to have a less painful and shorter labor is that shorter, less painful labor allows continued ambulation.

Other than the possibility of greater blood loss associated with the upright position during delivery, upright positions during most of labor are not associated with any harm to the mother or newborn and may aid maternal comfort. It is unclear whether birthing cushions or stools confer any benefit to the mother or the newborn.

Biofeedback

Biofeedback is a relaxation method that is used as an adjunct to the relaxation training taught in Lamaze classes and other childbirth education programs. Two biofeedback procedures may be applicable to the laboring woman: skin-conductance (autonomic) and electromyographic (voluntary muscle) relaxation. St. James-Roberts et al.79 demonstrated that electromyographic but not skin-conductance biofeedback techniques could be taught effectively in Lamaze classes. They noted no difference in length of the first stage of labor, use of epidural analgesia, incidence of instrumental delivery, or Apgar scores among electromyographic, skin-conductance, and control groups. In a small study, Duchene80 reported reduced pain perception during labor and delivery and a lower rate of epidural analgesia use (40% versus 70% for a control group) with electromyographic biofeedback; there was no difference between groups in Apgar scores. A recent Cochrane review assessing the effectiveness of biofeedback found that most studies had a high risk for bias, and although some studies demonstrated reduced use of analgesics with biofeedback there was insufficient evidence to conclude that biofeedback is efficacious.81 Biofeedback training does not appear to confer substantial benefit beyond that of traditional relaxation training taught in childbirth education classes.

Intradermal Water Injections

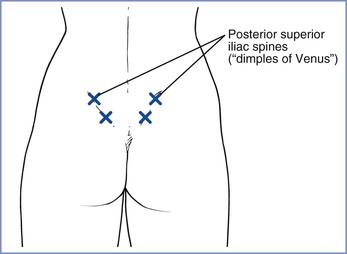

Intradermal or intracutaneous water injections are used to treat lower back pain, which is a common complaint during labor. The afferent nerve fibers that innervate the uterus and cervix, as well as the nerve fibers that innervate the lower back, all enter the spinal cord at the T10 through L1 spinal segments; therefore, a component of the pain may be referred pain. The technique consists of injecting 0.05 to 0.1 mL of sterile water, with an insulin or tuberculin syringe, at four sites on the lower back (i.e., over each posterior superior iliac spine, and at 1 cm medial and 3 cm caudad to the posterior superior iliac spine on both sides of the back, for a total of four injections) (Figure 21-3). The injections themselves are acutely painful for 20 to 30 seconds, but as the injection pain fades, so does lower back pain.

FIGURE 21-3 Placement of intradermal water blocks (x). Approximately 0.05 to 0.1 mL of sterile water is injected intradermally to form a small bleb over each posterior superior iliac spine and at 3 cm below and 1 cm medial to each spine on both sides of the back (i.e., for a total of four injections). The exact locations of the injections do not appear to be critical to the block success. (From Simkin P. Update on nonpharmacologic approaches to relieve labor pain and prevent suffering. J Midwifery Womens Health 2004; 49:489-504.)

Systematic reviews have summarized the four randomized controlled trials that compared intradermal water injections with placebo or standard care.48,66 The results of these trials suggested that the intradermal injections are a simple method of reducing severe low back pain during labor without adverse effects on the mother and fetus. The analgesic effect appears to last for 45 to 120 minutes47 but did reduce the rate of use of other analgesic techniques.48,66 However, a recent Cochrane review assessing the effectiveness of water injections during labor did not find evidence that it reduced back pain or labor pain.82

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) involves the transmission of low-voltage electrical current to the skin via surface electrodes. Advantages of TENS are that it is easy to use and discontinue, is noninvasive, and has no demonstrable harmful effects on the fetus. The only stated disadvantage is the occasional interference with electronic fetal heart rate monitoring. It is most widely used for childbirth in Scandinavia and the United Kingdom.47 Chao et al.83 evaluated the use of TENS at specific acupuncture points and observed a reduction in pain perception more commonly in the study group than in the control group. However, a systematic review of nine trials in more than 1000 women concluded that TENS did not reduce labor pain and did not reduce the use of additional analgesic agents.84 There also was no effect on the duration of labor or the incidence of instrumental delivery. Patients tend to rate the device as helpful despite the fact that it does not reduce the use of additional analgesics. Widespread use of TENS does not seem warranted.

Acupuncture/Acupressure

Traditional Chinese medicine includes extensive use of acupuncture. Given that acupuncture can provide analgesia, there is interest in its use for intrapartum analgesia, although this is not a traditional use of the method. Early observational reports described conflicting results as to the efficacy of intrapartum acupuncture. Given the historic lack of use of acupuncture in obstetric patients, there is a lack of standardization of the acupuncture points to be stimulated.

Several randomized, controlled trials have compared “real” acupuncture to “false” or “minimal” acupuncture using shallow insertion of needles in non-acupuncture points,85,86 whereas other investigators have used a control group that did not receive acupuncture.87,88 Four randomized trials found that pain scores were lower in women randomly assigned to receive acupuncture treatment, as was the rate of use of other modes of analgesia (e.g., epidural and systemic meperidine).85–88 These results suggest that acupuncture may hold promise for the treatment of labor pain.85–88 Hantoushzadeh et al.86 also observed a shorter duration of the active phase of labor and a reduction in use of oxytocin in the acupuncture group. No adverse maternal or fetal effects were identified. Other randomized studies did not find reduced pain scores with acupuncture.89,90

A randomized, controlled trial of acupressure (treatment) compared with touch (control) at the SP6 acupoint found lower pain scores and a shorter duration of labor in the acupressure group.91 A meta-analysis of 13 acupuncture trials including 1986 women concluded that acupuncture may hold promise for labor analgesia; however, larger studies are required for definitive conclusions.92 All of the randomized, controlled acupuncture studies were performed outside the United States, in countries (primarily Scandinavian) in which the use of neuraxial labor analgesia is less widespread than in the United States. Also, the use of acupuncture requires trained personnel. (Scandinavian midwives have been trained to administer acupuncture.) For these reasons it is unlikely that either acupuncture or acupressure will gain widespread acceptance in the United States for intrapartum analgesia.

Hypnosis

The use of hypnosis for obstetric analgesia is not new.93 Early proponents touted safety for the mother and the fetus, lower analgesic requirements, and shorter labor as the major advantages of intrapartum hypnosis. Whether hypnosis differs substantially from other childbirth preparation techniques is an unresolved controversy. Fee and Reilley94 concluded that the breathing and relaxation exercises used in childbirth preparation do not represent a hypnotic trance; support for their conclusion is provided by the successful teaching of childbirth preparation exercises to women who are not susceptible to hypnosis. However, women susceptible to hypnosis may achieve a state much like a hypnotic trance when using the same exercises.

Instruction in the techniques of self-hypnosis occurs before the onset of labor and may entail visits to the hypnotist or involvement in a childbirth education program such as HypnoBirthing. Proponents previously suggested that successful hypnosis training should begin early in the third trimester. Rock et al.95 found that hypnosis could be introduced to untrained, nonvolunteer patients during labor. On average, this maneuver added approximately 45 minutes of care; however, all but 3 of 22 patients in the experimental group required additional analgesia. Some studies found that hypnosis did not decrease analgesic requirements,96 but a recent review of 13 separate studies noted that hypnosis resulted in lower analgesic requirements and a shorter duration of the first stage of labor. The authors do not believe their findings are conclusive since most studies were not randomized.97

Childbirth preparation and hypnosis seem to have similar effects on obstetric outcome. Harmon et al.98 combined hypnosis and skill mastery with childbirth education. Experimental patients with a high susceptibility to hypnosis demonstrated less use of opioid, tranquilizer, and oxytocic medications; shorter first and second stages of labor; and a higher incidence of spontaneous vaginal delivery. Patients with a low susceptibility to hypnosis did not gain substantial advantage from the addition of hypnosis to the routine childbirth education provided for the control group.

In summary, hypnosis has at least the following three limitations: (1) antepartum training sessions are required, (2) trained hypnotherapists must be available during labor, and (3) it offers no clear benefit. Therefore, hypnosis is unlikely to attain widespread use during childbirth.

Implications for Anesthesia Providers

Childbirth preparation classes and nonpharmacologic analgesic techniques are not comparable to neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia for the relief of labor pain. Thus, some might wonder whether it is important or useful for anesthesia providers to have knowledge of these techniques. If our only obligation to the obstetric patient is a technical one (i.e., to eliminate pain safely with the use of neuraxial analgesia), knowledge of these techniques is perhaps superfluous. However, the practice of obstetric anesthesia should not be limited to the performance of pain-relieving procedures; our contributions to the care of the obstetric patient and her family should extend beyond the administration of neuraxial analgesia.

Much has been written in professional and lay journals concerning the “proper” childbirth experience. Each patient’s expectations of labor influence her childbirth experience. Yarrow99 described the results of a nonscientific poll of 72,000 readers of Parents Magazine, which revealed that there is an undeniable movement toward more family-centered maternity care. Women currently view childbirth from the perspective of educated consumers; they expect to have choices and a level of control during childbirth. We may not always be comfortable with this situation, but it is a reality for modern obstetric practice. Our challenge is to provide safe, effective analgesia in a nonthreatening, “homelike” environment. We are not solely responsible for a patient’s childbirth experience, but our interactions with the patient, her family, and her obstetrician will influence her perception of childbirth.

Anesthesia providers must become effective educators as well as health care providers. Patients should have realistic expectations about the pain of labor and the variability of individual labor patterns. They should be encouraged to define “success” as a positive childbirth experience regardless of the mode of delivery, use of analgesia and anesthesia, or other arbitrary definitions. An obstetrician advised prospective mothers100:

If you do end up choosing some form of pain relief during labor, do not feel inadequate if a friend had her baby without assistance. Some labors are more intense than others. Ultimately, holding your baby in your arms is more important than the method you used to bring her into the world.

Anesthesia providers may effectively provide similar advice. Unfortunately, anesthesia providers usually have little involvement in prenatal education classes. Our active participation in childbirth education classes may help patients receive more accurate information about the risks and benefits of analgesia/anesthesia for labor, vaginal delivery, and cesarean delivery. Anesthesia providers can encourage childbirth instructors to prepare patients for the unexpected and to acknowledge that the commonly described “typical” labor may, in fact, be atypical. Well-informed patients are more likely to accept the interventions that may become necessary during labor. Women with medical or obstetric diseases that may increase anesthetic risk should be encouraged to discuss these problems with an anesthesia provider before the onset of labor; thus, we must develop procedures to facilitate antepartum consultation. Beilin et al.101 found in a survey study that most women would prefer a pre-labor visit with their anesthesiologist. In summary, the active participation of the anesthesia provider in childbirth education will lead women to perceive the anesthesia provider as an integral part of the obstetric care team.

Some nonpharmacologic analgesic techniques may have benefits other than decreased pain perception. For example, some obstetricians and nurses believe that ambulation and subsequent squatting (or use of a birth cushion) shortens labor and increases the rate of spontaneous vaginal delivery. Even if this belief proves not to be true, many women prefer to be mobile during labor and, at a minimum, to retain the ability to walk to the bathroom. We should attempt to develop and use analgesic techniques that take advantage of these relatively simple maneuvers. For example, the use of intrathecal opioids during early labor allows for continued ambulation and the use of showers and/or tubs. Some techniques of epidural analgesia allow sitting with support. Finally, epidural analgesia/anesthesia does not eliminate the beneficial effects of other comfort measures, such as massage, and continued emotional support from family and friends.

Whenever possible, anesthesia providers should provide safe anesthetic care that is compatible with reasonable patient expectations. Future studies on the efficacy of childbirth education, nonpharmacologic analgesic techniques, and neuraxial analgesic techniques should evaluate the patient’s overall experience and satisfaction rather than limit assessment to the usual measures of obstetric outcome.102 In an editorial that accompanied the study by Bloom et al.,68 Cefalo and Bowes103 commented, “In the end, the nurses, midwives, and physicians who attend a woman with compassion, understanding, and professionalism are the most important factors in the management of any labor.”

References

1. Ziemer MM. Does prepared childbirth mean pain relief? Top Clin Nurs. 1980;2:19–26.

2. Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:277–299.

3. Reading AE. A comparison of the McGill Pain Questionnaire in chronic and acute pain. Pain. 1982;13:185–192.

4. Scott J, Huskisson EC. Graphic representation of pain. Pain. 1976;2:175–184.

5. Melzack R. The myth of painless childbirth (the John J. Bonica lecture). Pain. 1984;19:321–337.

6. Melzack R, Taenzer P, Feldman P, Kinch RA. Labour is still painful after prepared childbirth training. Can Med Assoc J. 1981;125:357–363.

7. Speert H. Obstetrics and Gynecology in America: A History. Waverly Press: Baltimore; 1980.

8. Wertz R, Wertz D. Lying-in: A History of Childbirth in America. The Free Press: New York; 1977.

9. Devitt N. The transition from home to hospital birth in the United States, 1930-1960. Birth Fam J. 1977;4:47–58.

10. Beck NC, Geden EA, Brouder GT. Preparation for labor: a historical perspective. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:243–258.

11. Dick-Read G. Childbirth Without Fear: The Principles and Practice of Natural Childbirth. Harper & Brothers: New York; 1944.

12. Dick-Reed G. Natural Childbirth. Heinemann: London; 1933.

13. Lamaze F. Painless Childbirth: Psychoprophylactic Method. Burke: London; 1958.

14. Velvovsky I, Platonov K, Ploticher V, Shugom E. Painless Childbirth Through Psychoprophylaxis: Lectures for Obstetricians. Foreign Languages Publishing House: London; 1960.

15. Karmel M. Thank You, Dr. Lamaze: A Mother’s Experiences in Painless Childbirth. Lippincott: New York; 1959.

16. Karmel M. Thank You, Dr. Lamaze: A Mother’s Experiences in Painless Childbirth. 2nd edition. Harper & Row: New York; 1981.

17. Leboyer F. Birth Without Violence. Knopf: New York; 1975.

18. Nelson NM, Enkin MW, Saigal S, et al. A randomized clinical trial of the Leboyer approach to childbirth. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:655–660.

19. Saigal S, Nelson NM, Bennett KJ, Enkin MW. Observations on the behavioral state of newborn infants during the first hour of life: a comparison of infants delivered by the Leboyer and conventional methods. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;139:715–719.

20. Pitcock CD, Clark RB. From Fanny to Fernand: the development of consumerism in pain control during the birth process. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:581–587.

21. Beck NC, Hall D. Natural childbirth: a review and analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1978;52:371–379.

22. Lindell SG. Education for childbirth: a time for change. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1988;17:108–112.

23. Lu MC, Prentice J, Yu SM, et al. Childbirth education classes: sociodemographic disparities in attendance and the association of attendance with breastfeeding initiation. Matern Child Health J. 2003;7:87–93.

24. Nelson MK. The effect of childbirth preparation on women of different social classes. J Health Soc Behav. 1982;23:339–352.

25. Zacharias JF. Childbirth education classes: effects on attitudes toward childbirth in high-risk indigent women. JOGN Nurs. 1981;10:265–267.

26. Copstick S, Hayes RW, Taylor KE, Morris NF. A test of a common assumption regarding the use of antenatal training during labour. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29:215–218.

27. Bernardini JY, Maloni JA, Stegman CE. Neuromuscular control of childbirth-prepared women during the first stage of labor. JOGN Nurs. 1983;12:105–111.

28. Stewart DE. Psychiatric symptoms following attempted natural childbirth. Can Med Assoc J. 1982;127:713–716.

29. Guzman Sanchez A, Segura Ortega L, Panduro Baron JG. Psychological reaction due to failure using the Lamaze method. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1985;23:343–346.

30. Behan M. Childbirth machismo. Parenting April. 1988;53–57.

31. Crittendon D. Knock me out with a truck. Wall Street Journal. 1992;A14 [November 6] .

32. Hetherington SE. A controlled study of the effect of prepared childbirth classes on obstetric outcomes. Birth. 1990;17:86–90.

33. Rogers CH. Type of medications used in labor by Lamaze and non-Lamaze prepared subjects and the effect on newborn Apgar scores using analysis of variance: a thesis. University of Alabama (Huntsville): Huntsville; 1981.

34. Scott JR, Rose NB. Effect of psychoprophylaxis (Lamaze preparation) on labor and delivery in primiparas. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:1205–1207.

35. Zax M, Sameroff AJ, Farnum JE. Childbirth education, maternal attitudes, and delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975;123:185–190.

36. Hughey MJ, McElin TW, Young T. Maternal and fetal outcome of Lamaze-prepared patients. Obstet Gynecol. 1978;51:643–647.

37. Delke I, Minkoff H, Grunebaum A. Effect of Lamaze childbirth preparation on maternal plasma beta-endorphin immunoreactivity in active labor. Am J Perinatol. 1985;2:317–319.

38. Brewin C, Bradley C. Perceived control and the experience of childbirth. Br J Clin Psychol. 1982;21:263–269.

39. Patton LL, English EC, Hambleton JD. Childbirth preparation and outcomes of labor and delivery in primiparous women. J Fam Pract. 1985;20:375–378.

41. Campbell D, Scott KD, Klaus MH, Falk M. Female relatives or friends trained as labor doulas: outcomes at 6 to 8 weeks postpartum. Birth. 2007;34:220–227.

42. Geden E, Beck NC, Brouder G, et al. Self-report and psychophysiological effects of Lamaze preparation: an analogue of labor pain. Res Nurs Health. 1985;8:155–165.

43. Geden EA, Beck NC, Anderson JS, et al. Effects of cognitive and pharmacologic strategies on analogued labor pain. Nurs Res. 1986;35:301–306.

44. Manderino MA, Bzdek VM. Effects of modeling and information on reactions to pain: a childbirth-preparation analogue. Nurs Res. 1984;33:9–14.

45. Worthington EL Jr, Martin GA. A laboratory analysis of response to pain after training three Lamaze techniques. J Psychosom Res. 1980;24:109–116.

46. Whipple B, Josimovich JB, Komisaruk BR. Sensory thresholds during the antepartum, intrapartum and postpartum periods. Int J Nurs Stud. 1990;27:213–221.

47. Simkin P, Bolding A. Update on nonpharmacologic approaches to relieve labor pain and prevent suffering. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2004;49:489–504.

48. Huntley AL, Coon JT, Ernst E. Complementary and alternative medicine for labor pain: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:36–44.

49. Gentz BA. Alternative therapies for the management of pain in labor and delivery. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2001;44:704–732.

50. Bertsch TD, Nagishima-Whalen L, Dykeman S, et al. Labor support by first-time fathers: direct observations. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 1990;11:251–260.

51. Henneborn WJ, Cogan R. The effect of husband participation on reported pain and probability of medication during labor and birth. J Psychosom Res. 1975;19:215–222.

52. Hofmeyr GJ, Nikodem VC, Wolman WL, et al. Companionship to modify the clinical birth environment: effects on progress and perceptions of labour, and breastfeeding. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;98:756–764.

53. Kennell J, Klaus M, McGrath S, et al. Continuous emotional support during labor in a US hospital: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1991;265:2197–2201.

54. Klaus MH, Kennell JH, Robertson SS, Sosa R. Effects of social support during parturition on maternal and infant morbidity. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293:585–587.

55. Campbell DA, Lake MF, Falk M, Backstrand JR. A randomized control trial of continuous support in labor by a lay doula. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35:456–464.

56. Hodnett ED, Gates S, Hofmeyr GJ, et al. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011.

57. Hodnett ED, Lowe NK, Hannah ME, et al. Effectiveness of nurses as providers of birth labor support in North American hospitals: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:1373–1381.

58. Birch ER. The experience of touch received during labor: postpartum perceptions of therapeutic value. J Nurse Midwifery. 1986;31:270–276.

59. Kimber L, McNabb M, McCourt C, et al. Massage or music for pain relief in labour: a pilot randomised placebo controlled trial. Eur J Pain. 2008;12:961–969.

60. Penny KS. Postpartum perceptions of touch received during labor. Res Nurs Health. 1979;2:9–16.

61. Cammu H, Clasen K, Van Wettere L, Derde MP. “To bathe or not to bathe” during the first stage of labor. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1994;73:468–472.

62. Eckert K, Turnbull D, MacLennan A. Immersion in water in the first stage of labor: a randomized controlled trial. Birth. 2001;28:84–93.

63. Rush J, Burlock S, Lambert K, et al. The effects of whirlpools baths in labor: a randomized, controlled trial. Birth. 1996;23:136–143.

64. Cluett ER, Pickering RM, Getliffe K St, George Saunders NJ. Randomised controlled trial of labouring in water compared with standard of augmentation for management of dystocia in first stage of labour. BMJ. 2004;328:314.

65. Cluett ER, Nikodem VC, McCandlish RE, Burns EE. Immersion in water in pregnancy, labour and birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(2).

66. Simkin PP, O’Hara M. Nonpharmacologic relief of pain during labor: systematic reviews of five methods. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:S131–S159.

67. Lawrence A, Lewis L, Hofmeyr GJ, et al. Maternal positions and mobility during first stage labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2).

68. Bloom SL, McIntire DD, Kelly MA, et al. Lack of effect of walking on labor and delivery. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:76–79.

69. Nageotte MP, Larson D, Rumney PJ, et al. Epidural analgesia compared with combined spinal-epidural analgesia during labor in nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1715–1719.

70. Collis RE, Harding SA, Morgan BM. Effect of maternal ambulation on labour with low-dose combined spinal-epidural analgesia. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:535–539.

71. Gardosi J, Hutson N, B-Lynch C. Randomised, controlled trial of squatting in the second stage of labour. Lancet. 1989;2:74–77.

72. Gupta JK, Leal CB, Johnson N, Lilford RJ. Squatting in second stage of labour. Lancet. 1989;2:561–562.

73. Johnson N, Johnson VA, Gupta JK. Maternal positions during labor. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1991;46:428–434.

74. Gupta JK, Glanville JN, Johnson N, et al. The effect of squatting on pelvic dimensions. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1991;42:19–22.

75. Shannahan MK, Cottrell BH. The effects of birth chair delivery on maternal perceptions. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1989;18:323–326.

76. Stewart P, Spiby H. A randomized study of the sitting position for delivery using a newly designed obstetric chair. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96:327–333.

77. Waldenstrom U, Gottvall K. A randomized trial of birthing stool or conventional semirecumbent position for second-stage labor. Birth. 1991;18:5–10.

78. Gupta JK, Hofmeyr GJ, Shehmar M. Position in the second stage of labour for women without epidural anaesthesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(5).

79. St James-Roberts I, Chamberlain G, Haran FJ, Hutchinson CM. Use of electromyographic and skin-conductance biofeedback relaxation training of facilitate childbirth in primiparae. J Psychosom Res. 1982;26:455–462.

80. Duchene P. Effects of biofeedback on childbirth pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1989;4:117–123.

81. Barragan Loayza IM, Sola I, Juando Prats C. Biofeedback for pain management during labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6).

82. Derry S, Straube S, Moore RA, et al. Intracutaneous or subcutaneous sterile water injection compared with blinded controls for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(1).

83. Chao AS, Chao A, Wang TH, et al. Pain relief by applying transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) on acupuncture points during the first stage of labor: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Pain. 2007;127:214–220.

84. Mello LF, Nobrega LF, Lemos A. Transcutaneous electrical stimulation for pain relief during labor: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Bras Fisioter. 2011;15:175–184.

85. Skilnand E, Fossen D, Heiberg E. Acupuncture in the management of pain in labor. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:943–948.

86. Hantoushzadeh S, Alhusseini N, Lebaschi AH. The effects of acupuncture during labour on nulliparous women: a randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47:26–30.

87. Ramnero A, Hanson U, Kihlgren M. Acupuncture treatment during labour—a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2002;109:637–644.

88. Nesheim BI, Kinge R, Berg B, et al. Acupuncture during labor can reduce the use of meperidine: a controlled clinical study. Clin J Pain. 2003;19:187–191.

89. Mackenzie IZ, Xu J, Cusick C, et al. Acupuncture for pain relief during induced labour in nulliparae: a randomised controlled study. BJOG. 2011;118:440–447.

91. Lee MK, Chang SB, Kang DH. Effects of SP6 acupressure on labor pain and length of delivery time in women during labor. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10:959–965.

92. Smith CA, Collins CT, Crowther CA, Levett KM. Acupuncture or acupressure for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7).

93. August RV. Hypnosis in Childbirth. McGraw Hill: New York; 1961.

94. Fee AF, Reilley RR. Hypnosis in obstetrics: a review of techniques. J Am Soc Psychosom Dent Med. 1982;29:17–29.

95. Rock NL, Shipley TE, Campbell C. Hypnosis with untrained, nonvolunteer patients in labor. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 1969;17:25–36.

96. Freeman RM, Macaulay AJ, Eve L, et al. Randomised trial of self hypnosis for analgesia in labour. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;292:657–658.

97. Landolt AS, Milling LS. The efficacy of hypnosis as an intervention for labor and delivery pain: a comprehensive methodological review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:1022–1031.

98. Harmon TM, Hynan MT, Tyre TE. Improved obstetric outcomes using hypnotic analgesia and skill mastery combined with childbirth education. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58:525–530.

99. Yarrow L. Giving birth: 72,000 moms tell all. Parents. 1992;67:525–530.

100. Stevenson-Smith F, Salmon D. Pain relief during labor. Parents. 1993;68:127.

101. Beilin Y, Rosenblatt MA, Bodian CA, et al. Information and concerns about obstetric anesthesia: a survey of 320 obstetric patients. Int J Obstet Anesth. 1996;5:145–151.

102. MacArthur C, Lewis M, Knox EG. Evaluation of obstetric analgesia and anaesthesia: long-term maternal recollections. Int J Obstet Anesth. 1993;2:3–11.

103. Cefalo RC, Bowes WA Jr. Managing labor—never walk alone. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:117–118.