Celiac plexus block

Indications

The celiac plexus provides sensory innervation and sympathetic outflow to most of the upper abdominal viscera (see Chapter 40). Neurolytic blockade of the celiac plexus is most commonly used to control pain caused by pancreatic cancer, although it can be useful for managing pain related to malignancies of the gastrointestinal tract from the lower esophageal sphincter to the splenic flexure, as well as the liver, spleen, and kidneys. Although potentially long-lasting, neurolytic celiac plexus block is not “permanent” because the nerves in the plexus regenerate in 3 to 6 months. The block can be repeated in such circumstances, but many patients with pancreatic cancer do not outlive the effective duration of neurolytic celiac plexus block. The median survival after diagnosis with pancreatic cancer is 3 to 6 months. Most patients with pancreatic cancer still require some oral analgesics even after neurolytic celiac plexus block.

Anatomy

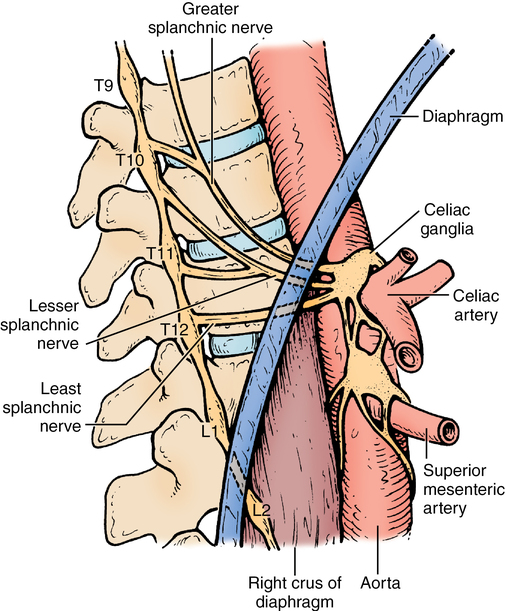

The celiac plexus is primarily a sympathetic nervous system structure that lies anterior to the aorta near the celiac arterial trunk (Figure 220-1). Preganglionic sympathetic fibers originate from the nerve roots of T5-T12 and combine to form the splanchnic nerves. The splanchnic nerves cross the crura of the diaphragm before joining the vagus nerve to form the celiac plexus anterior to the aorta. The location of the plexus varies from T12 to L2 vertebral levels; approaches to the block are directed at the T12-L1 level.

Procedure

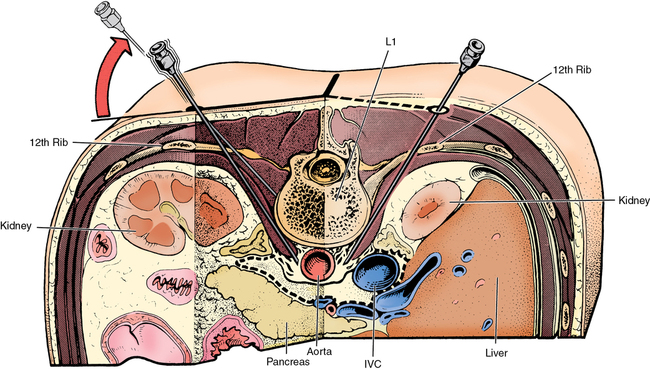

Several approaches to the celiac plexus have been described, including endoscopic, ventral, and dorsal. The endoscopic route is convenient when combined with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The ventral approach can be advantageous if tumor blocks the dorsal route, but it has a higher risk of bowel injury and infection. The most common route used by anesthesia providers is via the dorsal approach and is performed with the patient in the prone position with a pillow under the hips. Landmarks are identified and marked on the skin surface, indicating the twelfth rib and the thoracolumbar spinous processes. Needles are inserted bilaterally at a site approximately 7.5 cm lateral to midline at a point 2 cm inferior to the twelfth rib. The initial pass is directed to contact the L1 vertebral body at an angle approximately 45 degrees from the sagittal plane (Figure 220-2). The path of the needle is approximately parallel to the inferior border of the twelfth rib, directed toward the middle of the L1 vertebral body. After noting the depth at which bone is contacted, the needle is withdrawn to skin level and redirected more steeply, so that it passes just lateral to the L1 body, and is then advanced an additional 1 to 2 cm. Ideal positioning is anterolateral to the body of the L1 vertebral body.