Figure 1-1 Relationship of carcinogenic to mutagenic potencies of chemical compounds The ability to quantify both the mutagenic potencies of a variety of chemical compounds, measured in the Ames mutagenesis test, and to relate this to their carcinogenic potencies, as measured in laboratory rodents, allowed this graph and correlation to be made between the two mechanisms of action. (Adapted from Meselson M et al. In: Hiatt HH et al., eds., Origins of Human Cancer, Book C: Human Risk Assessment. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1977.)

The epigenetic model of cancer lost its attractiveness largely because an extensive array of mutant growth-controlling genes was discovered in the genomes of human tumor cells. So the focus shifted increasingly to genes, more specifically the genomes of cancer cells. Cancer genetics in the 1970s and early 1980s became a branch of somatic cell genetics—the genetics of cells and their somatically mutated genes. Indeed, advances in the technology of DNA sequencing have now enabled the enumeration of mutations present in specific cancer genomes and will eventually lead to a compendium of recurrent genetic alterations in human cancers.

The Discovery of Cellular Oncogenes

The notion that cancer cells were mutants should have motivated a systematic search for genes that suffered mutation during the development of tumors. Moreover, these mutant genes should possess another property: they needed to specify some of the aberrant phenotypes ascribed to tumor cells, including alterations in cell shape, decreased dependence on external mitogenic stimuli, and an ability to grow without tethering to a solid substrate (anchorage independence). The fact that viruses were not important causative agents of most types of human tumors generated another conclusion about these cancer-causing genes: they were likely to be endogenous to the cell rather than being imported into the cell from some external source. Stated differently, it seemed likely that these cancer genes were mutant versions of preexisting normal cellular genes.

In the 1970s, when this line of thinking matured, the experimental opportunities to test its validity were limited. The human genome, which harbored these hypothetical cancer genes, represented daunting complexity. Its vastness precluded any simple, systematic survey strategy designed to locate mutant growth-controlling genes within cancer cells. Indeed, it is only now, three decades later, that the means, deep sequencing of cancer genomes, for conducting effective systematic surveys for cancer genes has been developed. Thus the discovery of cancer-causing genes—oncogenes as they came to be called—depended on a circuitous, indirect experimental strategy.

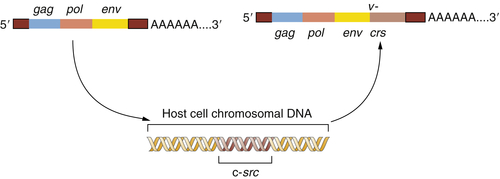

Ironically, it was tumor viruses, in the midst of being discredited as important etiologic agents of human cancer, that led the way to finding the elusive cancer genes. Varmus and Bishop’s study of the Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) broke open the puzzle. Their initial agenda was to understand the replication strategy of this chicken virus. However, in the years after 1974, they focused their attentions to unraveling the mechanism used by RSV to transform an infected normal cell into a tumor cell.

Earlier work of others had indicated that a single gene, named src, carried the vital cancer-causing information present in the viral genome. Accordingly, the Varmus and Bishop laboratory launched a research program to trace the origins of this virus-associated src oncogene. In fact, the origins of most viral genes were obscure, shrouded in the deep evolutionary past. It seemed that most viruses and thus their genes originated hundreds of millions of years ago, perhaps as derivatives of the cells that they learned to parasitize.

However, as this team reported in 1976, the

src gene behaved differently: it was a recent acquisition by the Rous virus. Many closely related retroviruses shared with RSV an ability to replicate in chicken cells and a very similar set of genes needed for viral replication. However, these other viruses lacked the

src gene and the ability to transform infected cells into cancer cells, suggesting that the

src oncogene carried by RSV was a relatively recent genetic acquisition. The Varmus-Bishop group soon traced the origins of the

src gene to an unexpected source—a closely related gene that resided in the genome of normal chickens and, by extension, in the genomes of all vertebrates. They named this gene c-

src (cellular

src) to distinguish it from the v-

src (viral

src) oncogene carried by the virus.

4 The Varmus-Bishop evidence converged on a simple conceptual model. It explained all their observations and ultimately much more. The progenitor of RSV lacked the

v-

src gene but grew well in chicken cells. During one of its periodic forays into a chicken cell, this ancestor virus picked up a copy of the c-

src gene and incorporated it into its own viral genome. Once

src was present within the viral genome, this slightly remodeled gene—now v-

src—was exploited by RSV to transform cells it encountered in subsequent rounds of infection.

Figure 1-2 The origin of the Rous sarcoma virus src oncogene The acquisition of the v-src oncogene by a precursor of Rous sarcoma virus apparently occurred when an avian leukosis virus (ALV) lacking this oncogene infected a chicken cell and appropriated the cellular c-src proto-oncogene, thereafter carrying this acquired gene and exploiting it to transform subsequently infected cells.

This provided a testimonial to the cleverness and plasticity of retroviruses, which seemed able to capture and then exploit normal cellular genes to do their bidding. But another implication was even more important: the Varmus-Bishop work pointed to the existence of a normal cellular gene, the c-

src gene, that seemed to possess a latent ability to induce cancer. This cancer-causing ability was unmasked when the c-

src gene was abducted by the chicken retrovirus that became the progenitor of RSV (

Figure 1-2 ).

The c

-src gene was named a

proto-oncogene to indicate its inherent potential to become activated into a cancer-causing oncogene. Within several years, it became clear that as many as a dozen other tumorigenic retroviruses also carried oncogenes, each of which had been abstracted from the genome of an infected vertebrate cell.

5,6 Hence, there were many proto-oncogenes in the normal cell genome, not just c-

src. Each seemed to be present in the DNA of a normal mammalian or avian host species, and by extension, present as well in the genomes of all vertebrates.

These discoveries were momentous because they demonstrated that normal cellular genes had the ability to induce cancer if removed from their normal chromosomal context and placed under the control of one or another retrovirus. Still, a key piece was missing from this puzzle. Retroviruses seemed to be absent from most, indeed from almost all, human tumors. Could proto-oncogenes ever become activated without direct intervention by a marauding retrovirus?

An obvious response was that proto-oncogenes might be altered by mutational events that did not remove these genes from their normal chromosomal roosts. Instead, these mutations would alter proto-oncogenes in situ in the chromosome by affecting either the control sequences or the protein-encoding sequences of these genes. This notion led to another question: If some proto-oncogenes could become activated by somatic mutations, such as those inflicted by chemical or physical carcinogens, would these be the same proto-oncogenes that were the targets of mobilization and activation by retroviruses?

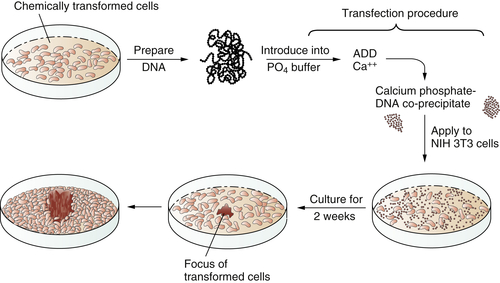

In 1979 and 1980, answers came, once again from unexpected quarters. These newer experiments depended on the use of gene transfer, also known as transfection. The transfection procedure could be used to convey DNA, and thus genes, from tumor cells into normal recipient cells. The goal here was to see whether the transferred tumor cell DNA could induce some type of malignant transformation in the recipient cells. Success in such an experiment would indicate that the transferred gene(s) previously operated in the donor tumor cell to induce its transformation.

These transfection experiments succeeded (

Figure 1-3 ). DNA extracted from chemically transformed mouse fibroblasts was able to induce normal mouse fibroblasts to undergo transformation.

7 Retroviruses were clearly absent from both the donor tumor cells and the recipients that underwent transformation and so could not be invoked to explain the cancer-causing powers of the transferred DNA. Soon the identity of these transferred genes, which functioned as oncogenes, became apparent. They were members of the

ras family of oncogenes, which had initially been discovered through their association with rodent sarcoma viruses.

5,8 These rodent retroviruses had acquired

ras proto-oncogenes from normal rodent cells, much like RSV, which had stolen a copy of the

src proto-oncogene from a chicken cell.

Unanswered by this was the genetic mechanism that imparted oncogenic powers to the tumor-associated

ras oncogene, more specifically an H-

ras oncogene. It soon became clear that the tumor-associated H-

ras oncogene was closely related to, indeed virtually indistinguishable from, a normal H-

ras proto-oncogene that was present in the genomes of all vertebrates. Still, the tumor-associated

ras oncogene carried different information than did the precursor proto-oncogene: the oncogene caused the malignant transformation of cells into which it was introduced, whereas the counterpart proto-oncogene had no obvious effects on cell phenotype. This particular puzzle was solved in 1982 with the finding that an H-

ras oncogene cloned from a human bladder

carcinoma carried a point mutation—a single nucleotide substitution—that distinguished it from its counterpart proto-oncogene.

9–11 This genetic alteration, clearly a somatic mutation, sufficed to convert a normally benign proto-oncogene into a virulent oncogene.

Figure 1-3 Transfection of a cellular oncogene The fact that the carcinogenicity of various chemical compounds was correlated with their mutagenicity suggested that cancer cells often carry mutant, cancer-inducing genes, i.e., oncogenes, in their genomes. This could be proven by an experiment in which DNA was extracted from chemically transformed mouse fibroblasts and introduced, via the procedure of transfection, into untransformed mouse fibroblasts. The appearance of foci of transformed cells in the latter indicated the transmission of a transforming gene from the donor to the recipient cells, indicating that chemical carcinogens could indeed generate a mutant, cancer-causing gene.

Within months, yet other activated oncogenes were found in human tumors by using DNA probes prepared from a variety of retrovirus-associated oncogenes. The

myc oncogene, initially associated with avian myelocytomatosis virus, was found to be present in increased gene copy number (i.e., amplified) in some human hematopoietic tumors

12 ; in yet others,

myc was activated through a chromosomal translocation that juxtaposed its coding sequences with those of immunoglobulin genes, thereby placing the expression of the

myc gene under the control of these antibody genes rather than its own normal transcriptional control elements.

13 These discoveries extended and solidified a simple point: a common repertoire of proto-oncogenes could be activated either by retroviruses (usually in animal tumors) or by somatic mutations (in human tumors). The activating mutations involved either base substitution, amplification in gene copy number, or chromosomal translocation.

Multistep Tumorigenesis

The discoveries of mutant, tumor-associated oncogenes in human tumors led to a simple model of cancer formation. Mutagenic carcinogens entered into cells of a target tissue and mutated a proto-oncogene. The resulting oncogene then induced the now-mutant cell to initiate a program of malignant growth. Eventually, years later, the progeny of this mutant founder cell formed a large enough mass to become a macroscopically apparent tumor.

While satisfying conceptually, this simple model of cancer formation clearly conflicted with a century’s worth of histopathologic analyses, which had indicated that tumor formation is really a multistep process, in which initially normal cell populations pass through a succession of intermediate stages on their way to becoming frankly malignant. Each of these intermediate stages contains cells that were more aberrant than those seen in the preceding steps. This body of observations persuaded many that the formation of a malignancy depended on a succession of phenotypic changes in the cells forming these various growths. Quite possibly, each of these shifts in cell phenotype reflected a change in the underlying genetic makeup of the evolving pre-malignant cell population. Such a multistep genetic model of tumor progression stood in direct conflict with the single-hit model of transformation that was suggested by the discovery of the point-mutated ras oncogene.

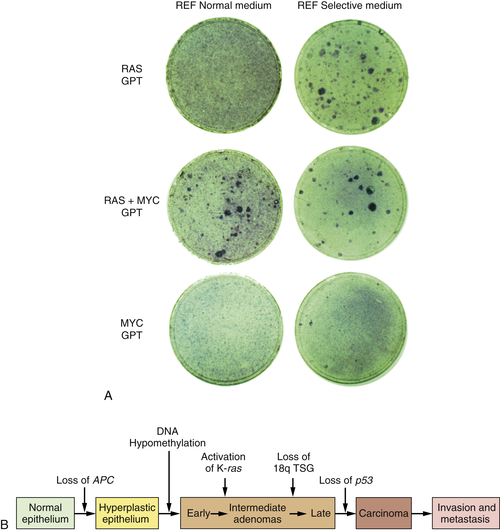

By 1983, one solution to this dilemma became apparent. In that year, experiments showed that a single introduced oncogene could not transform fully normal rat cells into ones that were tumorigenic. Two and maybe even more oncogenes seemed to be required to effect this conversion.

14,15 For example, whereas an introduced

ras oncogene could not transform normal embryo cells into tumor cells, the co-introduction of a

ras plus a

myc oncogene, or a

ras plus an adenovirus E1A oncogene, succeeded in doing so. It appeared that such pairs of oncogenes collaborated with one another to induce the full malignant transformation of normal cells (

Figure 1-4 ,

A). Moreover, this experiment suggested that human tumors carried two or more mutant oncogenes that collaborated with one another to orchestrate the many aberrant phenotypes associated with highly malignant cells.

Observations such as these pointed to a new way of conceptualizing the multistep tumorigenesis long studied by the pathologists. It seemed plausible that each of the

histopathological transitions arising during tumor development occurred as a consequence of a new mutation sustained in the genome of an evolving, premalignant cell population (

Figure 1-4,

B). According to this thinking, tumor development was a form of Darwinian evolution, in which each successive mutation in a growth-controlling gene conferred increased proliferative potential and thus selective advantage on the cells bearing the mutant gene.

16,17 Ultimately, a multiply mutated cell bearing half a dozen or more mutant genes might exhibit all of the phenotypes associated with highly malignant cancer cells.

Figure 1-4 Multistep tumorigenesis in vitro and in vivo (A) The ability of oncogenes to collaborate to transform cells in vitro was illustrated in this 1983 experiment in which neither a ras nor a myc oncogene was found able to induce foci when introduced into early passage rat embryo fibroblasts (REFs). However, when the two were introduced concomitantly, transformation ensued, as indicated by the appearance of foci. This suggested that tumor progression in vivo might involve a succession of mutations that created multiple collaborating cellular oncogenes. (B) By 1989, analyses of the genomes of colonic epithelial cells at various stages of tumor progression revealed that the more progressed the cells were, the more mutations they had acquired. In fact, some of the indicated mutations involved inactivation of tumor suppressor genes, to be discussed later. (A, from Land H, Parada LF, Weinberg RA. Nature. 1983;304:596-602; B, courtesy B. Vogelstein.)

This mechanistic model was validated through the creation of transgenic mice. Cloned copies of mutant oncogenes, such as ras and myc, were introduced into the germlines of mice. These transgenes were structured so that the oncogene was placed under the control of a transcriptional promoter that ensured expression of the resulting “transgene” in a specific tissue or developmental stage. Now the presence of a mutant oncogene in a particular tissue could be guaranteed through the actions of an appropriately engineered transgene rather than being dependent on the random actions of mutagenic carcinogens.

In one highly instructive group of experiments, a

myc or a

ras oncogene was placed under the control of the mouse mammary tumor virus transcriptional promoter, which guaranteed its expression in the mammary epithelium of

the pregnant female mouse.

18 As anticipated, these mice contracted breast cancer at extremely high rates. This demonstrated that mutant oncogenes were far more than markers of cancer progression; indeed, they could actually play a causal role in driving tumor pathogenesis.

Significantly, the transgenic mice did not contract cancer rapidly in their mammary tissue even though a mutant oncogene was implanted and expressed in virtually all of the epithelial cells of their mammary glands. Instead, their mammary carcinomas arose with several months’ delay, indicating that a second (and perhaps third) alteration was required in addition to the activated transgene before mammary epithelial cells launched a program of malignant growth. The nature of this additional alteration(s) was not always clear, but it almost certainly involved stochastic somatic mutations striking the mammary epithelial cells, creating mutant growth-controlling genes that collaborated with the transgene to trigger the outgrowth of malignant cell clones. In the years that followed, this work was extended to many types of human tumors, the cells of which were found to possess multiple mutant genes that contributed to tumor formation.

The Discovery of Tumor Suppressor Genes

The model of multistep tumorigenesis implied that a tumor cell carries two or more mutant oncogenes, each activated by somatic mutation during one of the stages of tumor development. However, experimental validation of this model initially proved to be difficult. Most attempts at detecting mutant oncogenes in human tumor genomes yielded a ras or perhaps a myc oncogene, but rarely were two mutant oncogenes found to coexist in the genomes of human tumor cells. This left two logical alternatives. Either the genome of a typical human tumor cell did not contain multiple mutated genes, as the multistep model of cancer suggested, or there were indeed multiple mutated cancer-causing genes in tumors, but many of these were not oncogenes of the type that had been studied intensively in the 1970s and early 1980s.

In fact, there were candidate genes waiting in the wings. These others operated in a fashion diametrically opposite to that of the oncogenes: they seemed to prevent cancer rather than favoring it and came to be called “tumor suppressor genes.” Several independent lines of evidence led to the discovery and characterization of these genes.

Experiments using cell hybridization initiated by Henry Harris in Oxford provided the first indication of the existence of these suppressor genes.

19 These cell hybridizations involved the physical fusion of two distinct types of cells that were propagated in mixed cultures. The conjoined cells would form a common hybrid cytoplasm and ultimately pool their chromosomes, yielding a hybrid genome.

Often these cell hybridizations involved the fusion of cells with two distinct genotypes. In some of these experiments, tumor cells were fused with normal cells. The motive here was to see which genome would dominate in determining the behavior of the resulting hybrids. Counter to the expectations of many, the resulting hybrid cells turned out, more often than not, to be nontumorigenic.

19 This indicated that the genes present in the normal genome dominated over those carried in the cancer cell. In the language of genetics, the normal alleles were dominant, whereas the cancer cell–associated alleles were recessive. (More properly, the alleles present in the cancer cell created a phenotype that was recessive to the normal cell phenotype.)

This unanticipated behavior could most easily be rationalized by assuming that normal cells carried certain growth-normalizing genes, the presence of which was needed to maintain normal proliferation. Cancer cells seemed to have lost these genes, ostensibly through mutations that resulted in inactivated versions of the genes present in normal cells. When reintroduced into the cancer cells via cell fusion, the normal alleles reimposed control on the cancer cells, restoring their behavior to that of a normal cell. In effect, these growth-normalizing genes suppressed the tumorigenic phenotype of the cancer cells and were, for this reason, termed tumor suppressor genes (TSGs).

In their normal incarnations, the TSGs seemed to constrain growth, unlike the proto-oncogenes, which seemed to be involved in promoting normal proliferation. Inactivated, null alleles of TSGs were found in tumor cell genomes in contrast to the hyperactivated alleles of proto-oncogenes (i.e., oncogenes) found in these genomes.

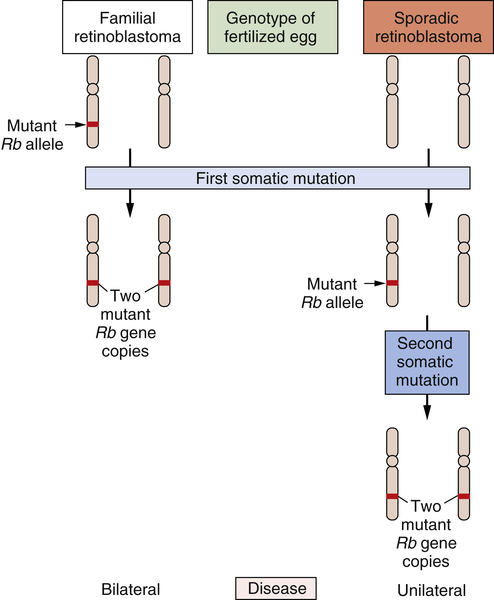

The study of retinoblastoma, the childhood eye tumor, converged on these cell hybridization studies in a dramatic way. This work had been pioneered by Alfred Knudson, who, beginning in the early 1970s, studied the genetics of this rare tumor. Knudson learned much by comparing the two forms of this cancer: sporadic retinoblastoma, which seemed to be due exclusively to accidental somatic mutations, and familial retinoblastoma, which appeared, like many familial cancers, to be due to the transmission of a mutated gene in the germline.

Knudson’s analysis of the kinetics of retinoblastoma onset persuaded him that a common set of gene(s) operated to generate both kinds of tumors.

20,21 Although the nature of these genes eluded him, their number was clear. Sporadic retinoblastomas seemed to arise following two successive somatic mutations affecting a lineage of cells in the retina. The triggering of familial retinoblastomas seemed to require only a single somatic mutation. Knudson speculated that in these familial tumors, a second mutated gene was required

to trigger tumorigenesis and that this gene was already present in mutant form in all the cells of the retina, having been inherited in mutated form from a parent of the affected child.

For the cancer geneticist, Knudson’s most important concept was the notion that a retinal cell needed to lose two mutant genes before it was transformed into a tumor cell. Sometimes one of the two mutant null alleles was contributed by the germline; more often, both genes arose through somatic mutation. However, the nature of these genes and the mutations that recruited them into the tumorigenic process remained elusive. Finally, in 1979, karyotypic analysis of a retinoblastoma revealed an interstitial deletion in the q14 band of chromosome 13.

22 Later work revealed that this resulted in the loss of a gene, termed

RB. Hence, one of the two mutational events needed to make a retinoblastoma involved the inactivation of an

RB gene copy, in this particular case through the wholesale deletion of the chromosomal region carrying the

RB gene.

By 1983, the nature of the second mutational event became clear: it involved the loss of the second, hitherto intact copy of the

RB gene.

23 Hence, the two mutational events hypothesized by Knudson involved the successive inactivation of the two copies of this gene. Suddenly, the need for two mutations became clear: The first mutation left the cell with a single, still-intact copy of the

RB gene, which was able, on its own, to continue programming normal proliferation. Only when this surviving gene copy was eliminated from the cell genome did runaway proliferation begin (

Figure 1-5 ). Thus, mutations that inactivate an

RB gene copy create alleles that function recessively at the cellular level. Only when both wild-type alleles are lost through various mutational mechanisms does a retinal cell begin to behave abnormally.

The

RB gene became the paradigm for a large cohort of similarly acting TSGs that suffer inactivation during tumor progression. These TSGs are scattered throughout the cell genome and act through a variety of cell-physiologic mechanisms to control cell proliferation.

24 They are united only by the fact that they control proliferation in a negative way, so that their loss permits uncontrolled cell multiplication to proceed.

The discovery of the

RB gene gave substance and specificity to the genes that Harris had postulated from his cell fusion experiments. Equally important, they opened the door to understanding a variety of familial cancer syndromes. In the case of

RB, inheritance of a mutant, defective allele predisposes to retinoblastoma early in life with more than 90% probability. Inheritance of a defective allele of the

APC TSG predisposes with high frequency to adenomatous polyposis coli syndrome and thus to colon cancer. The presence of a mutant

TP53 gene in the germline leads to increased rates of tumors in a number of organ sites, including sarcomas and carcinomas, yielding the Li-Fraumeni syndrome. More than two dozen heritable cancer syndromes have been associated with germline inheritance of defective TSGs.

25,26

Figure 1-5 Genetics of retinoblastoma development The development of retinoblastomas requires the successive inactivation of two copies of the chromosomal RB gene. In the case of familial retinoblastomas, one of the two copies of this gene is already mutated in one or another gamete and is transmitted to the offspring, who is therefore heterozygous at this locus in all cells of the body; subsequent loss, through somatic alterations, of the surviving wild-type gene copy leaves a retinal cell with no functional copies of this gene, enabling tumor formation to begin. In sporadic retinoblastomas, the conceptus is genetically wild type; however, two successive somatic mutations occurring in a lineage of retinal precursor cells leaves some of these cells, once again, without functional RB gene copies, and as before permits retinoblastoma tumorigenesis to begin.

In each case, the inheritance of a mutant, functionally defective TSG allele obviates one of two usually required somatic mutations. Because an inactivating somatic mutation represents a low-probability event per cell generation, the presence of an already-mutant inherited TSG allele enormously accelerates the overall kinetics of tumor formation. As a consequence, the likelihood of a tumor arising during the course of a normal lifespan is enormously increased.

The search for TSGs has been difficult, as their existence only becomes apparent when they are absent from a cellular genome. However, one peculiarity of TSG genetics has greatly aided the discovery of these genes. This involves the genetic mechanisms by which the second copy of a TSG is lost. In principle, two independent somatic mutations could successively inactivate the two copies of a TSG,

thereby liberating a cell from the growth-constraining influences of this gene. However, each of these mutations normally occurs with a low probability—perhaps 10

−6 per cell generation. The likelihood of both mutations occurring is therefore roughly 10

−12 per cell generation, an extremely low probability. (Actually, because cancer cell genomes become progressively destabilized as tumors develop, this probability is usually higher.)

In fact, evolving premalignant cell populations carrying a single, already-inactivated TSG copy often resort to another genetic mechanism to eliminate the second, still-intact copy of this TSG. They discard the chromosomal arm (or chromosomal region) carrying the still-intact TSG copy and replace it with a duplicated copy of the chromosomal region carrying the mutant, already-inactivated TSG copy. All this is achieved via the exchange of genetic material between paired homologous chromosomes.

The end result of these genetic gymnastics is the duplication of the mutant TSG copy. Thus, the TSG goes from a heterozygous state (involving one mutant and one wild-type gene allele) to a homozygous state (involving two mutant gene copies). Almost always, the chromosomal region flanking the TSG suffers the same fate. Consequently, known genes as well as other genetic markers within this flanking region that were initially present in a heterozygous configuration now become reduced to a homozygous configuration. This genetic behavior has motivated cancer geneticists to analyze the genomes of human tumor cells, looking for chromosomal regions that repeatedly suffer loss of heterozygosity (LOH) during tumor progression. Such LOHs represent presumptive evidence for the presence of TSGs in these regions whose second wild-type copies have been eliminated by LOH during the course of tumor development. Once such a region is localized to a chromosomal region, several currently available gene molecular strategies can be exploited to further narrow the chromosomal domain carrying the TSG and ultimately to isolate the TSG through molecular cloning.

The existence of many dozen still-unknown TSGs is suspected because of the documented LOH affecting specific chromosomal regions of various types of human tumor cells. The effort to identify and clone these genes is being greatly facilitated by efforts such as those included in the International Cancer Genome Consortium and the Cancer Genome Anatomy Project (TCGA). Nonetheless, the successful identification and cloning of a significant cohort of TSGs has already provided one solution to a major puzzle posed earlier. As mentioned, although human tumor cells were hypothesized to carry a number of distinct, mutated growth-controlling genes, most tumors appeared to carry only a single activated oncogene. We now realize that many of the other targets of mutation during tumor progression are TSGs. Their inactivation collaborates with the activated oncogenes to create malignant cells and thus tumors. In the widely cited study of human multistep tumor progression—that described in colonic tumors by Vogelstein and his co-workers—the mutation of a K-

ras oncogene is accompanied by mutations of the

APC and

TP53 TSGs and a third TSG that maps to chromosome 18.

27 This evidence, together with a wealth of genetic studies reported subsequently, indicates that TSGs are inactivated even more frequently than oncogenes are activated during the course of forming many types of human tumors. Importantly, the inactivation of TSGs often phenocopies the cell-biological effects of oncogenes. This means that the inactivation of TSGs is as important to the biology of tumor progression as oncogene activation.

Unexpectedly, the discovery of TSGs also made it possible to understand how a variety of DNA tumor viruses succeed in transforming the cells that they infect. Unlike retroviruses, these DNA viruses carry oncogenes that have resided in their genomes for millions, and likely hundreds of millions, of years. Any connections with antecedent cellular genes, to the extent they once existed, were obscured long ago by the extensive remodeling that these oncogenes underwent while being carried in the genomes of the various DNA tumor viruses. Independent of their ultimate origins, it was clear in the 1980s that the oncogenes (and encoded oncoproteins) were deployed by DNA viruses to perturb key components of the normal cellular growth-controlling circuitry. However, the precise control points targeted by these viral oncoproteins remained obscure.

In the late 1980s, it was learned that a number of DNA tumor virus oncoproteins bind to the products of two centrally important TSGs, pRB and p53.

28,29 For example, the large T oncoprotein of SV40 binds and sequesters both the p53 and pRB proteins of infected host cells; the E6 and E7 oncoproteins of human papillomaviruses target p53 and pRB, respectively. As a consequence, a virus-infected cell is deprived of the services of these two key negative regulators of its proliferation. Indeed, these virus-mediated inactivations closely mimic the state seen in many nonviral tumors that have been deprived of pRB and p53 function by somatic mutations striking the TSGs specifying these two proteins. So the transforming mechanisms used by these viruses could be rationalized by referring to the same genes and proteins that were known to be inactivated by mutational mechanisms in many types of spontaneous, nonviral human tumors. Importantly, these findings reinforced the notion that a single, central growth-regulating machinery operating in all types of cells suffers disruption by a variety of ostensibly unrelated genetic mechanisms, leading eventually to the formation of cancers.

The activation of oncogenes and the loss of TSGs together explain many of the phenotypes that one associates with cancer cells. These cells are able to grow without attachment to solid substrate, the aforementioned phenotype of anchorage

independence, and they are able to grow on top of one another, which is manifested in culture as the loss of contact inhibition. Moreover, when compared to normal cells, cancer cells exhibit a greatly reduced dependence on mitogens and an ability to resist the antiproliferative effects of growth-inhibitory signals, such as those conveyed by transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). Alterations of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes can be invoked to explain these neoplastic cell traits.

Arguably the most interesting trait of cancer cells is their ability to resist a variety of stimuli and stresses that would cause normal cells to activate the cell-suicide program termed apoptosis. The fact that virtually all tumor cells have developed various types of resistance to apoptosis indicates that severe pro-apoptotic stresses are experienced repeatedly as normal cells evolve progressively toward a malignant phenotype and that an ability to resist these stresses is strongly selected during this evolution. Thus, changes in the complex array of genes that control entrance in the apoptotic program are frequently demonstrable within tumor cells. Although these genes are specialized in regulating a discrete cancer cell phenotype (apoptosis), they behave operationally like oncogenes and TSGs, i.e., the activation of some of these confers a resistance to apoptosis as does the inactivation of yet others.

Guardians of the Genome

As mentioned previously, the somatic mutations that activate oncogenes or inactivate TSGs are relatively rare events in the life of a cell, occurring perhaps at a rate of 10

−6 per cell generation. This low mutation frequency represents an important barrier to the development of neoplasia.

30 If cells require multiple mutations in order to progress to a fully malignant growth state, the probability of the entire constellation of mutations occurring within a cell lineage during a normal human lifespan is extremely low. This provides a partial explanation for the fact that we humans develop relatively few cancers during lifespans in which the cells in our bodies undergo more than 10

16 divisions, each of which represents an opportunity for a genetic disaster.

As described earlier, the inheritance of a mutant growth-controlling gene obviates one of the normally required, rare somatic mutational steps. In doing so, it allows a population of premalignant cells to leapfrog over one of the barriers that usually block its progression toward malignancy. The consequence is the greatly increased risk of certain tumors that characterizes familial cancer syndromes.

However, there is at least one other route by which this multistep tumor pathogenesis can be accelerated: if the rate of gene mutation per cell generation is greatly increased, the time required for a population of cells to surmount all of the mutational hurdles and progress to full-blown malignancy will be correspondingly reduced. As a consequence, the probability of cancer striking during a normal lifespan will be greatly increased.

Xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) is the most thoroughly studied of the inborn cancer susceptibility syndromes that are attributable to greatly increased mutational frequency. Those suffering from XP show abnormally high sensitivity to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, which evokes squamous cell skin carcinomas and melanomas at exposed sites at a high rate. Like the rest of us, XP patients sustain large numbers of mutational events in their skin cells created by ultraviolet photons. In the skin cells of most humans, the pyrimidine dimers created by UV radiation are quickly excised from the damaged DNA and the initial, wild-type nucleotide sequence is restored, thereby erasing all traces of the mutation; this removal of DNA lesions is achieved by a cohort of DNA repair proteins that are specialized to effect this particular alteration of DNA structure. (In the event that skin cells exhibit widespread genomic damage that overwhelms the ability of its DNA repair apparatus to restore normal genome sequence, the cell may opt for another response, apoptosis, as discussed later.) In the XP patient, one or another essential component of this specialized DNA repair apparatus is absent or defective.

31 As a consequence, altered DNA sequences are transmitted to the progeny of the initially irradiated cell, resulting in large numbers of mutations in their genomes. Hence, the effective mutation rate (the number of initially induced mutations minus those that are repaired) increases enormously.

XP represented only the first of the familial cancer syndromes that has been attributable to defective DNA repair. In this particular syndrome, mutational damage is inflicted by an exogenous mutagen—UV radiation. We now know that a variety of other familial cancer syndromes are also attributable to defects in one or another component of the complex apparatus that maintains the integrity of our genome. In many of the more recently characterized cancer syndromes, the initial mutational damage is of endogenous origin, being inflicted by malfunctioning of normal cellular processes, including the mutations that result from mistakes in DNA replication and from the actions of endogenously generated mutagens, such as reactive oxygen species.

The ataxia telangiectasia syndrome, which includes, among its presentations, the development of certain tumors, is also due to defective DNA repair.

31,32 In hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC), the apparatus that recognizes recently made mistakes in DNA replication, often termed the

mismatch repair apparatus, is defective.

33,34 At least four different inherited subtypes of HNPCC have been described; each of these is due to defects in one or another component of the complex multicomponent system that recognizes and erases DNA copying mistakes as well as other

lesions that are occasionally inflicted on the cell genome. In the cells of HNPCC patients, one sees widespread genomic instability, the direct results of this defective DNA repair. The resulting genetic damage seems to affect all genes with equal frequency and thus the target proto-oncogenes and TSGs that participate in the formation of non-HNPCC colon cancers. As a consequence, the entire multistep process of colon cancer progression is greatly accelerated. Unexplained at present is why this genetic defect specifically afflicts the colon rather than causing elevated rates of cancer incidence in many sites throughout the body.

Many familial breast cancers have more recently been associated with inheritance of mutant versions of the

BRCA1 and

BRCA2 genes.

35 These were initially thought to be TSGs, but the peculiar behavior of the mutant alleles of these genes suggested otherwise. Mutant alleles of the

BRCA1 and

BRCA2 genes were found to be inherited in the germlines of affected individuals; however, sporadic mammary tumors rarely showed mutant alleles. Recent biochemical and cell biological experiments suggest that both these genes specify proteins that participate in the repair of double-strand DNA breaks. It remains unclear why the inheritance of defective alleles of either of these genes predisposes individuals specifically to breast and ovarian tumors.

There is increasing evidence that a breakdown of DNA repair capability accompanies the formation of the great majority of human tumors. These losses may occur through somatic mutation of DNA repair genes or, perhaps more frequently, through epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation (see later discussion), that succeed in repressing the expression of these repair genes, thereby depriving cells of the vital functions encoded by these genes.

Epigenetic Mechanisms Leading to Loss of Gene Function

As described earlier, the functions of two major classes of cellular genes are lost during the course of tumor progression—TSGs and DNA repair genes. It is highly likely that the development of the great majority of human tumors depends on these losses. Moreover, the portrayal of cancer as a genetic disorder, as developed previously, would suggest that these genes and their vital functions are lost through various mechanisms of somatic mutation. After all, mutations are by definition heritable, and thus the progeny of a cell that has initially acquired growth advantage through some somatic mutation will be similarly benefited, leading to the progressive expansion of clones of such mutant cells.

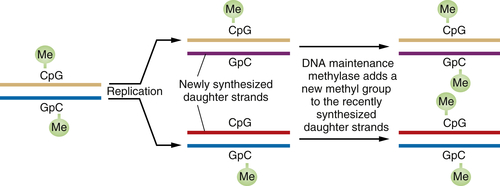

Following this logic, the phenotypic changes that occur during the course of tumor progression need to be heritable. In fact, there is a mechanism of heritability that does not depend on genetic alterations, i.e., on alterations of nucleotide sequence in a cell’s genome. This mechanism depends on the methylation of the cytidine residues present in CpG dinucleotide sequences that are found in proximity to the promoters of various genes or by modification of histones in chromatin. Methylation or modification of histones often results in major shifts in the configuration of nearby chromatin and in the shutdown of the expression of nearby genes—the process of transcriptional repression.

When a DNA segment containing a methylated CpG is replicated, the complementary CpG in the newly synthesized daughter DNA strand is initially unmethylated. However, soon after this daughter strand is formed, “maintenance” DNA methylases recognize the hemimethylated DNA and attach a methyl group to the recently formed CpG residue, thereby ensuring that both CpGs are now methylated (

Figure 1-6 ). This scheme ensures that DNA methylation events, and thus associated repression of certain genes, can be transmitted from parent to daughter cells with high fidelity. Hence, genes may be inactivated in a heritable fashion without any change in their nucleotide sequence.

In fact, the mechanisms that control DNA methylation result in the inactivation of genes at higher rates per cell generation than those involving somatic mutations. This leads to the obvious conclusion that the functions of TSGs and DNA repair genes are likely to be lost more frequently through DNA methylation than mutation, a notion that

is borne out by extensive studies of the genomes of human tumor cells.

36 Indeed, it now seems likely that individual tumor cell genomes bear many dozens if not hundreds of methylated genes. Most of these genes are likely be methylated as a consequence of the relaxed controls on DNA methylation that seem to operate within cancer cells; most such genes are bystanders, i.e., their loss is not functionally important for the cancer cell phenotype and their loss has not conferred selective advantage on the cells that carry them. However, a number of key TSGs and DNA repair genes have indeed been found to be methylated frequently in various types of human cancer cell genomes, and it is clear that the loss of gene function through promoter methylation is as effective in driving tumor progression as the somatic mutations that have been described extensively here.

Figure 1-6 Perpetuation of CpG methylation following DNA replication When DNA methylated at CpG residues is replicated, the newly formed daughter strands initially lack methyl groups on the CpG sites complementary to those methylated sequences in the parental DNA strands. However, shortly after replication, maintenance methylases add methyl groups to the newly synthesized CpG sites, ensuring the transmission of the methylated state from one cell generation to the next. Such methylation is often associated with the repression of gene transcription.

Moreover, the modification of histones also alters chromatin and gene expression. Recent genome sequencing efforts have uncovered mutations in genes whose products play key roles in maintaining or modifying histone marks. For example, mutations in adenine-thymine (AT)-rich interactive domain-containing protein 1A (ARID1A),

36,37 a protein involved in chromatin remodeling, is mutated in more than 50% of ovarian clear cell cancers, and multiple chromatin-modifying enzymes including PBRM1 are mutated in a large fraction of renal clear cell cancers. These findings provide a link between the genetic and epigenetic origins of cancer. Hence, cancer pathogenesis is a disorder of genes and gene function, but it does not always depend on genetic alterations, because the epigenetic regulation of genes contributes as frequently, if not more frequently, to tumor formation.

Immortalized Proliferation

Yet another phenotype of cancer cells—their ability to grow and divide indefinitely—does indeed depend on changes in DNA structure and is, in this sense, a genetically determined trait. This unlimited proliferative ability, often termed

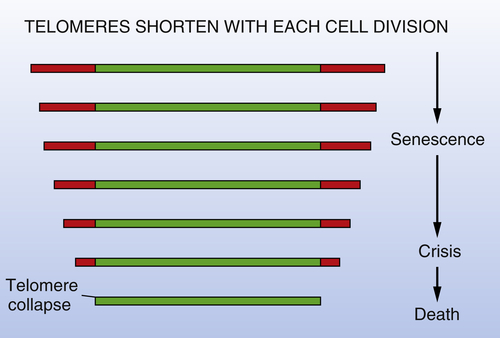

cell immortality, stands in stark contrast to the limited proliferative ability of normal cell populations. Thus, when placed into culture, many types of cancer cells are able to proliferate indefinitely, in contrast to the behavior of normal cells, which cease proliferation after a limited, ostensibly predetermined number of doublings. This phenomenon of finite replicative potential suggests the workings of some type of generational clock that tallies the number of cell divisions through which cell lineages have passed since they resided in the early embryo and then informs cells in these lineages when their allotment of doublings has been exhausted. In response to this alarm, cell populations become “senescent,” and if they overcome or circumvent senescence, will multiply further until they enter into a state of “crisis,” in which almost all of them die.

38,39 This limitation on replicative potential would seem to represent an important antineoplastic barrier erected by the organism. By limiting the number of successive replicative doublings its component cells may undertake, the organism erects a high barrier to the unlimited expansion of preneoplastic cell clones. Cancer cells must surmount this barrier in order to succeed in their agenda of unlimited growth and the formation of macroscopic tumors.

In fact, very different mechanisms govern the timing of the entrance of cell populations into senescence and into crisis. The senescence observed with cultured cells appears to be determined, in large part, by the conditions of their propagation in vitro. By necessity, the protocols developed for culturing cells create conditions that differ dramatically from those operating within living tissues. These discrepancies derive from the contents of the culture medium as well as the oxygen tensions experienced by cells within tissue culture incubators. As a consequence, cells suffer substantial physiologic stress when placed into culture, and cumulative cell-physiologic stress seems to be a major, if not the major, determinant of the triggering of senescence.

The mechanisms governing entrance into crisis are very different and do indeed involve, quite directly, the cell genome, more specifically the telomeres at the ends of all chromosomes. Evidence accumulated in recent years points to the telomeres as the molecular devices that tally cell generations and govern entrance into crisis. The ends of the telomeric DNA are not copied completely during each cycle of DNA replication because of an intrinsic limitation in the DNA polymerases responsible for the bulk of DNA replication. In addition, the ends of telomeric DNA are susceptible to the actions of exonucleases, which contribute to further erosion of telomeric DNA length. As a consequence, the telomeres shorten progressively as cell lineages pass through repeated cycles of growth and division (

Figure 1-7 ). In normal cell lineages, this shortening eventually results in critically truncated telomeres. Without the protective effects of the telomeres, chromosomes undergo end-to-end fusion with resulting karyotypic instability and cell death. Hence, the progressive shortening of telomeres represents an effective molecular device for counting cumulative generational doublings.

38,39 Cancer cell populations must overcome this limitation on their proliferation in order to proliferate extensively and generate macroscopic tumors. They do so by activating expression of the telomerase enzyme, which is able to restore and maintain telomeric DNA length, thereby reversing the effects of telomere erosion. Telomerase activity is detectable in almost all human tumors (approximately 90%) but is present at low or undetectable levels in the corresponding

normal tissues. Accordingly, the genes that allow telomerase activation during tumor progression represent yet additional important genetic elements that are affected during the development of almost all human tumors. Importantly, however, the human telomerase gene, termed

hTERT, is not itself the target of mutation. Instead, its expression is induced by a complex array of

trans-acting transcriptional regulators, the MYC oncoprotein being one of these.

Figure 1-7 Telomere erosion and entrance into crisis In the absence of active intervention by the telomerase enzyme, the telomeres of human chromosomes shorten progressively during each round of cell growth-and-division, eventually losing so much length that they can no longer subserve their normal function of protecting the ends of chromosomal DNA from end-to-end fusions with other chromosomes. This leads to massive cell death, termed crisis, and occasionally, the emergence of a rare variant that has indeed acquired telomerase expression and is accordingly now able to repair and maintain telomeric DNA and thus telomeres. (Although the onset of senescence is indicated here as also being triggered by telomere shortening, it appears that it is largely due to cumulative cell-physiologic stresses sustained by cells both in vitro and in vivo.)

The critical contribution of telomerase to tumorigenesis is illustrated most dramatically by the protocols that enable the experimental transformation of normal human cells into tumor cells. By adding the

hTERT gene to a cocktail of other introduced oncogenes, a variety of normal human cells can be converted to a tumorigenic state, as judged by their behavior following implantation into appropriate host mice.

40 The

hTERT gene clearly affords such cells the ability to proliferate indefinitely; without its actions, cells fail to proliferate extensively in vitro and to form tumors in vivo.

Non-genetic Mechanisms Accelerating Multistep Tumor Progression

The descriptions of tumorigenesis, as developed here, lead to the notions that the functioning of normal cell genomes is progressively degraded by mutagenic mechanisms, promoter methylation, and telomerase erosion and that these mechanisms conspire to drive forward multistep tumor progression. An obvious corollary is that exposure to high levels of mutagenic agents is likely to serve as a major agent that stimulates human tumor formation. Indeed, since the initial experiments of Bruce Ames, such logic has inspired the search for the mutagens that are responsible for instigating human cancers.

In truth, with some notable exceptions, the search for the mutagenic carcinogens that drive human cancer pathogenesis has failed.

41 Tobacco smoke, with its high levels of mutagens, is clearly responsible for almost one-third of human cancers. In addition, the heterocyclic amine mutagens created by the cooking of red meat at high temperatures are attractive candidates for the agents causing many colon and possibly prostate cancers.

In general, however, the carcinogens responsible for most human cancer incidence have eluded identification, apparently because they do not function as mutagens. Instead, it has become increasingly apparent over the past two decades that the major determinants of human cancer incidence are various agents and conditions that operate as “tumor promoters.” Thus, as illustrated by the classic experiments involving mouse skin cancers, tumor “initiators” are responsible for triggering the first step of multistep tumorigenesis by mutating certain target genes (e.g., H-ras), whereas promoters are responsible for driving the clonal expansion of already-initiated tumor cells, doing so through mechanisms that do not involve genetic damage. It seems increasingly likely that most of the determinants of human cancer incidence operate as promoters.

Possibly the most important promoting mechanisms involve chronic inflammation of tissues and the associated release of growth-stimulating factors by the irritated tissue. Moreover, many of the dietary determinants of tumor incidence would seem to function as promoters rather than as mutagenic initiators. If these notions are sustained by future research, this will mean that a complete understanding of cancer pathogenesis at the molecular level will require detailed elucidation of these non-genetic, tumor-promoting mechanisms.

Invasive and Metastatic Behaviors

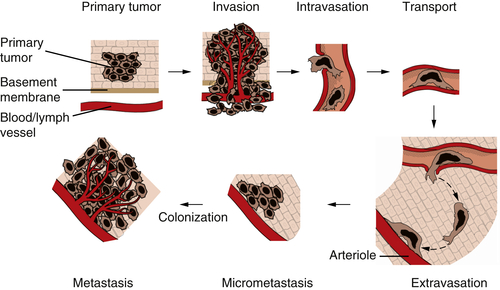

In many individuals, the endpoint of multistep tumor progression involves, unfortunately, the acquisition by cancer cells of the ability to invade and to metastasize from the primary tumor to distant sites in the body—the manifestations of high-grade malignancy. Indeed, the metastases that are spawned by malignant tumors are responsible for 90% of cancer-associated mortality.

Figure 1-8 The invasion-metastasis cascade The invasion-metastasis cascade is a complex, multistep process through which cancer cells must pass in order to launch macroscopic tumor colonies at distant sites. These steps are executed relatively inefficiently, resulting in vast numbers of cells being disseminated from primary tumors with only a small number of cells being able to eventually form macroscopic metastases.

The formation of metastases is the result of a complex, multistep process that is often termed the

invasion-metastasis cascade (

Figure 1-8 ). Thus, cancer cells in the primary tumor acquire the ability to invade adjacent tissue, to enter into the vessels of the blood and lymphatic systems (intravasation), to travel in these channels to distant sites in the body, to escape from these vessels (extravasation) into nearby tissues, and to found small tumor colonies (micrometastases) in these tissues. On occasion, the cells forming a micrometastasis will acquire the ability to proliferate vigorously, resulting in the formation of a macroscopic metastasis—the process termed

colonization. The complexity of the invasion-metastasis cascade rivals that of the multistep process that leads initially to the formation of a primary tumor. This suggests, in turn, that cancer cells within a primary tumor must suffer a significant number of genetic alterations in order to acquire the ability to complete this cascade. Another alternative has presented itself, however, as the result of recent research on the malignant behavior of carcinoma cells. This alternative mechanism involves the actions of genes that are normally involved in programming certain key steps of early embryonic morphogenesis. In such steps of embryogenesis, epithelial cells, which are normally immobilized in various layers, undergo a profound change in their differentiation program and acquire many of the phenotypes of mesenchymal cells, including motility and invasiveness. This transdifferentiation program is termed the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).

As many as half a dozen transcription factors acting during various stages of early embryogenesis are capable of programming EMTs. These transcription factors have names such as Snail, Slug, Twist, Goosecoid, and SIP-1. Each of these is able to act pleiotropically to program an EMT and thereby is able to cause the repression of epithelial genes and the induction, in their stead, of mesenchymal genes. Increasing experimental evidence indicates that carcinoma cells exploit these early embryonic genes in order to execute most of the steps of the invasion-metastasis cascade.

42,43 Expression of these embryonic genes seems to be induced by contextual signals that these carcinoma cells experience in the tumor microenvironment and that originate in the tumor-associated stroma. For example, TGF-β impinging on certain cancer cells is able to elicit the expression of several of the transcription factors that are capable, in turn, of programming an EMT. This suggests that the EMT program, and the enabling of the invasion-metastasis cascade, occurs because of a collaboration between the genotype of cancer cells and the contextual signals that these cells receive from the nearby microenvironment, more specifically from the activated stroma that is present in many primary tumors. Moreover, it suggests that certain carcinoma cell genotypes render these cells responsive to such stromal, EMT-inducing signals, whereas other genotypes leave the cancer cells unresponsive, indeed refractory, to these signals; our understanding of these genotypes is still fragmentary.

The discovery of these embryonic transcription programs and their resurrection by carcinoma cells greatly simplifies our conceptualization of the late stages of malignant progression. Rather than needing to acquire a number of distinct mutations in order to execute the various steps of the invasion-metastasis cascade, the genotypes of certain primary cancer cells allow them, in response to stromal signals, to activate long-dormant cell biological programs—EMTs. Once activated, this program seems to enable a carcinoma cell to complete most of the steps of the invasion-metastasis cascade. However, the last step—colonization—appears to involve an adaptation to the novel tissue microenvironment in which disseminated carcinoma cells have landed; such adaptation would not seem to be found among the multiple powers of the EMT program and would seem to acquire yet other changes that remain poorly understood.

Interestingly, the carcinoma cells forming a metastasis often recapitulate the histopathological appearance of the primary tumor, including its distinctive epithelial cell sheets and ducts. This would seem to be at variance with the notion that in order to metastasize, carcinoma cells must shed their epithelial characteristics and acquire, instead, mesenchymal ones. It seems plausible, however, that once carcinoma cells have disseminated and landed in distant tissue sites, they no longer encounter the mix of signals that were released by the activated stroma of the primary tumor and that led initially to their passing through an EMT. This new tissue microenvironment may therefore allow these cells to revert, via a mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) to the epithelial phenotype of their progenitors in the primary tumor, thereby generating once again epithelial histomorphology. Importantly, although passage through a partial or complete EMT may explain the malignant behavior of many carcinoma cells, it is less clear how tumors of other tissue origins, namely those arising in neuroectodermal, mesenchymal, and hematopoietic tissues, acquire these aggressive traits. The mechanisms enabling invasive and metastatic behaviors in these other neoplastic cell types remain elusive.

Other Phenotypes of Neoplasia

Many of the phenotypes of cancer cells are not readily explained by alterations in their proto-oncogenes and TSGs. Cancer cells acquire other aberrations that favor their growth in the complex environments of living tissues. Included among these is their ability to recruit blood vessels into tumor masses—the process of angiogenesis

44 —and, quite possibly, their ability to evade and overwhelm immune defenses.

45 The process of tumor angiogenesis, like the EMT, involves a complex array of heterotypic interactions between cancer cells and their mesenchymal microenvironment (

Figure 1-9 ). Indeed, this neoangiogenesis has become a subject of intensive investigation over the past decade, in part because the demonstrated dependence of tumors on vascularization represents an attractive target for therapeutic intervention through the creation and implementation of various antiangiogenic therapies. Thus, without adequate vascularization, cancer cells are limited to forming tumors of less than 1-mm diameter.

The processes of neovascularization depend on the heterotypic interactions of cancer cells with circulating endothelial precursor cells and with existing endothelial cells in the nearby stroma. Moreover, other regulators of this process include macrophages, myofibroblasts, and neutrophils, which may collaborate with the cancer cells to release angiogenic signals and thereby recruit endothelial cells and induce them to construct microvasculature. In addition, pericytes, which form the outer wall of most microvessels, must be recruited in order to ensure the assembly of well-constructed microvessels.

Figure 1-9 Tumor angiogenesis As tumors grow, they develop large networks of blood vessels through the process of angiogenesis. Seen here is a tumor (black mass, right) that has attracted blood vessels growing into it from adjacent normal tissue (left). As is the case with most tumor-associated neovasculature, the new vessels developed here are tortuous and often end in dead ends (right), in contrast to the normal vasculature seen here. (Reproduced from Weinberg RA. The Biology of Cancer. New York, NY: Garland Science; 2007:562.)

The role of the immune system in defending against the formation of various human tumor types remains a matter of great contention. Actually, in the case of virus-induced cancers, the protective role of the immune system is no longer debated, because of the abundant evidence that immunocompromised individuals suffer dramatically increased rates of virus-induced malignancies, including Kaposi’s sarcoma, human papillomavirus–induced squamous cell carcinomas, and certain types of Epstein-Barr virus–induced hematopoietic disorders. In all of these cases, these functions can be readily rationalized by invoking the known antiviral effects of the immune system.

More challenging, however, are the actions of the immune system in reducing the incidence of tumors of nonviral etiology, which constitute more than 80% of the total tumor burden in the population. In these cases, it has been unclear how the immune system can recognize tumor cells as being of foreign origin and proceed to attack and eliminate them. That such attack often occurs is clear, however, as evidenced by the severalfold increased incidence of a variety of common tumors in patients who are immunocompromised

for various reasons, largely involving the preservation of organ transplants. This phenomenon provides hope that the immune system is indeed capable of recognizing and attacking nonviral tumors and that its powers can be exploited to serve as antitumor therapeutic modalities.

The molecular genetic paradigm described here has allowed us to understand the workings of the cancer cell in enormous detail. Thirty years ago, no one could have anticipated this explosion of knowledge. Genes have led to encoded proteins, and the study of these proteins has allowed us to elucidate complex regulatory circuits transmitting signals that flux through the cancer cell and control its proliferation, differentiation, and death.

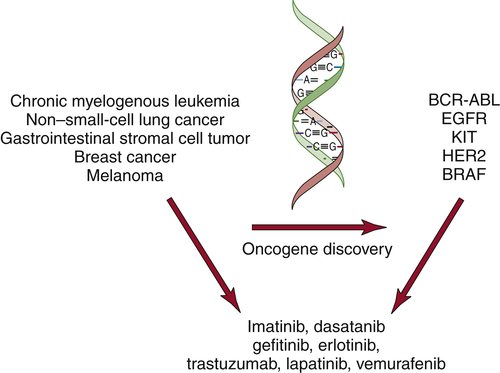

The discovery of oncogenes has begun to have an impact in the clinic. Small-molecule inhibitors or antibodies directed against activated oncogenes, such as BRAF, BCR-ABL, and HER2, are now approved for the treatment of melanoma, chronic myelogenous leukemia, and breast cancer (

Figure 1-10 ). In addition, large-scale efforts to characterize cancer genomes have confirmed the key role for many of the known oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes and uncovered new classes of potential cancer targets.

46–52 These efforts have also stimulated the development of strategies to perform genome characterization of patient samples. The extension of such efforts is likely to fundamentally alter the diagnosis and classification of cancers. Although it is clear that these initial molecularly targeted therapies will not lead to durable cures in most cases, with the greatly increased understanding of the genetic mechanisms of cancer pathogenesis, many novel ways of detecting and curing tumors are now, finally, within reach.

Figure 1-10 Molecularly targeted therapies The discovery of oncogenes in specific types of human cancers has led to the development of molecularly targeted inhibitors. These inhibitors show specificity for cancers that harbor the specific mutations.

References

1. Knipe D.M. , Howley P.M. , eds. Fields Virology . Philadelphia, PA : Lippincott Williams & Wilkins ; 2007 .

2. McCann J. , Choi E. , Yamasaki E. , Ames B.N. Detection of carcinogens as mutagens in the Salmonella/microsome test: assay of 300 chemicals . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 1975 ; 72 ( 12 ) : 5135 – 5139 .

3. zur Hausen H. Viruses in human cancers . Science . 1991 ; 254 ( 5035 ) : 1167 – 1173 .

4. Stehelin D. , Varmus H.E. , Bishop J.M. Vogt PK. DNA related to the transforming gene(s) of avian sarcoma viruses is present in normal avian DNA . Nature . 1976 ; 260 ( 5547 ) : 170 – 173 .

5. Bishop J.M. Cellular oncogenes and retroviruses . Annu Rev Biochem . 1983 ; 52 : 301 – 354 .

6. Weiss R. , Teich N. , Varmus H. Molecular Biology of Tumor Viruses: RNA Tumor Viruses . Cold Spring Harbor, NY : Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press ; 1985 .

7. Shih C. , Shilo B.Z. , Goldfarb M.P. , Dannenberg A. , Weinberg R.A. Passage of phenotypes of chemically transformed cells via transfection of DNA and chromatin . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 1979 ; 76 ( 11 ) : 5714 – 5718 .

8. Der C.J. , Krontiris T.G. , Cooper G.M. Transforming genes of human bladder and lung carcinoma cell lines are homologous to the ras genes of Harvey and Kirsten sarcoma viruses . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 1982 ; 79 ( 11 ) : 3637 – 3640 .

9. Reddy E.P. , Reynolds R.K. , Santos E. , Barbacid M. A point mutation is responsible for the acquisition of transforming properties by the T24 human bladder carcinoma oncogene . Nature . 1982 ; 300 ( 5888 ) : 149 – 152 .

10. Tabin C.J. , Bradley S.M. , Bargmann C.I. et al. Mechanism of activation of a human oncogene . Nature . 1982 ; 300 ( 5888 ) : 143 – 149 .

11. Taparowsky E. , Shimizu K. , Goldfarb M. , Wigler M. Structure and activation of the human N-ras gene . Cell . 1983 ; 34 ( 2 ) : 581 – 586 .

12. Alitalo K. , Schwab M. Oncogene amplification in tumor cells . Adv Cancer Res . 1986 ; 47 : 235 – 281 .

13. Leder P. , Battey J. , Lenoir G. et al. Translocations among antibody genes in human cancer . Science . 1983 ; 222 ( 4625 ) : 765 – 771 .

14. Land H. , Parada L.F. , Weinberg R.A. Tumorigenic conversion of primary embryo fibroblasts requires at least two cooperating oncogenes . Nature . 1983 ; 304 ( 5927 ) : 596 – 602 .

15. Ruley H.E. Adenovirus early region 1A enables viral and cellular transforming genes to transform primary cells in culture . Nature . 1983 ; 304 ( 5927 ) : 602 – 606 .

16. Hunter T. Cooperation between oncogenes . Cell . 1991 ; 64 ( 2 ) : 249 – 270 .

17. Nowell P.C. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations . Science . 1976 ; 194 ( 4260 ) : 23 – 28 .

18. Sinn E. , Muller W. , Pattengale P. Tepler I, Wallace R, Leder P. Coexpression of MMTV/v-Ha-ras and MMTV/c-myc genes in transgenic mice: synergistic action of oncogenes in vivo . Cell . 1987 ; 49 ( 4 ) : 465 – 475 .

19. Harris H. Cell fusion and the analysis of malignancy . Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci . 1971 ; 179 ( 54 ) : 1 – 20 .

20. Knudson Jr. A.G. Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 1971 ; 68 ( 4 ) : 820 – 823 .

21. Knudson A.G. Two genetic hits (more or less) to cancer . Nat Rev Cancer . 2001 ; 1 ( 2 ) : 157 – 162 .

22. Yunis J.J. , Ramsay N. Retinoblastoma and subband deletion of chromosome 13 . Am J Dis Child . 1978 ; 132 ( 2 ) : 161 – 163 .

23. Cavenee W.K. , Dryja T.P. , Phillips R.A. et al. Expression of recessive alleles by chromosomal mechanisms in retinoblastoma . Nature . 1983 ; 305 ( 5937 ) : 779 – 784 .

24. Weinberg R.A. Tumor suppressor genes . Science . 1991 ; 254 ( 5035 ) : 1138 – 1146 .

25. Fearon E.R. Human cancer syndromes: clues to the origin and nature of cancer . Science . 1997 ; 278 ( 5340 ) : 1043 – 1050 .

26. Vogelstein B. , Kinzler K.W. The Genetic Basis of Human Cancer . New York, NY : McGraw-Hill ; 1998 .

27. Fearon E.R. , Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis . Cell . 1990 ; 61 ( 5 ) : 759 – 767 .

28. Levine A.J. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division . Cell . 1997 ; 88 ( 3 ) : 323 – 331 .

29. Nevins J.R. E2F: a link between the Rb tumor suppressor protein and viral oncoproteins . Science . 1992 ; 258 ( 5081 ) : 424 – 429 .

30. Loeb L.A. Mutator phenotype may be required for multistage carcinogenesis . Cancer Res . 1991 ; 51 ( 12 ) : 3075 – 3079 .

31. Friedberg E.C. , Walker G.C. , Siede W. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis . Washington, DC : ASM Press ; 1995 .

32. Shiloh Y. ATM and related protein kinases: safeguarding genome integrity . Nat Rev Cancer . 2003 ; 3 ( 3 ) : 155 – 168 .

33. Heinen C.D. , Schmutte C. , Fishel R. DNA repair and tumorigenesis: lessons from hereditary cancer syndromes . Cancer Biol Ther . 2002 ; 1 ( 5 ) : 477 – 485 .

34. Modrich P. , Lahue R. Mismatch repair in replication fidelity, genetic recombination, and cancer biology . Annu Rev Biochem . 1996 ; 65 : 101 – 133 .

35. Venkitaraman A.R. Cancer susceptibility and the functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2 . Cell . 2002 ; 108 ( 2 ) : 171 – 182 .

36. Jones S. , Wang T.L. , Shih I.M. et al. Frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling gene ARID1A in ovarian clear cell carcinoma . Science . 2010 ; 330 ( 6001 ) : 228 – 231 .

37. Wiegand K.C. , Shah S.P. , Al-Agha O.M. et al. ARID1A mutations in endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas . N Engl J Med . 2010 ; 363 ( 16 ) : 1532 – 1543 .

38. Shay J.W. , Wright W.E. Hayflick, his limit, and cellular ageing . Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol . 2000 ; 1 ( 1 ) : 72 – 76 .

39. Shay J.W. , Zou Y. , Hiyama E. Wright WE. Telomerase and cancer . Hum Mol Genet . 2001 ; 10 ( 7 ) : 677 – 685 .

40. Hahn W.C. , Weinberg R.A. Rules for making human tumor cells . N Engl J Med . 2002 ; 347 ( 20 ) : 1593 – 1603 .

41. Gold L.S. , Ames B.N. , Slone T.H. Misconceptions about the causes of cancer . In: Paustenbach D.J. , ed. Human and Environmental Risk Assessment: Theory and Practice . New York, NY : John Wiley & Sons ; 2002 .

42. Savagner P. Leaving the neighborhood: molecular mechanisms involved during epithelial-mesenchymal transition . Bioessays . 2001 ; 23 ( 10 ) : 912 – 923 .

43. Thiery J.P. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression . Nat Rev Cancer . 2002 ; 2 ( 6 ) : 442 – 454 .

44. Ferrara N. VEGF and the quest for tumour angiogenesis factors . Nat Rev Cancer . 2002 ; 2 ( 10 ) : 795 – 803 .

45. Dunn G.P. , Bruce A.T. , Ikeda H. Old LJ, Schreiber RD. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape . Nat Immunol . 2002 ; 3 ( 11 ) : 991 – 998 .

46. Parsons D.W. , Jones S. , Zhang X. et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme . Science . 2008 ; 321 ( 5897 ) : 1807 – 1812 .

47. Wood L.D. , Parsons D.W. , Jones S. et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers . Science . 2007 ; 318 ( 5853 ) : 1108 – 1113 .

48. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma . Nature . 2011 ; 474 ( 7353 ) : 609 – 615 .

49. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network . Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways . Nature . 2008 ; 455 ( 7216 ) : 1061 – 1068 .

50. Bamford S. , Dawson E. , Forbes S. et al. The COSMIC (Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer) database and website . Br J Cancer . 2004 ; 91 ( 2 ) : 355 – 358 .

51. Campbell P.J. , Stephens P.J. , Pleasance E.D. et al. Identification of somatically acquired rearrangements in cancer using genome-wide massively parallel paired-end sequencing . Nat Genet . 2008 ; 40 ( 6 ) : 722 – 729 .

52. Greenman C. , Stephens P. , Smith R. et al. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes . Nature . 2007 ; 446 ( 7132 ) : 153 – 158 .

The Molecular Basis of Cancer Expert Consult - Online