26 Bypass Surgery for Complex Basilar Trunk Aneurysms

Clinical presentation

Mid- and lower-basilar aneurysms are uncommon lesions, accounting for fewer than 1% of all aneurysms in most neurosurgical series.1,2 Yamaura et al. reported a frequency of 5% (10/202) for posterior circulation aneurysms.3 In contrast, Drake and Peerless and Peerless et al. reported that mid- and lower-basilar aneurysms accounted for 15.2% (193/1266) of all posterior circulation aneurysms.4,5 Undoubtedly, however, this higher incidence reflected the referral bias of their institution.

The clinical features of ruptured aneurysms in the mid- and lower-basilar artery location tend to be indistinguishable from subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) from other cerebral aneurysms. As with any SAH, sudden headache, nuchal pain, altered mental status, nausea, and vomiting are the typical manifestations. Intraparenchymal bleeding, which can be associated with anterior circulation aneurysms, is rarely a feature of these aneurysms. As with other posterior circulation aneurysms, the natural history of these aneurysms appears to be that of high rupture rates.5 Unruptured giant aneurysms can produce neurological symptoms specific to their anatomic location, ranging from isolated cranial neuropathies to brainstem compression syndromes.

Fusiform and dissecting aneurysms are more common in the posterior circulation than in the anterior circulation and are associated with a poor prognosis.6 Large dolichoectatic aneurysms involving the basilar trunk and vertebral arteries may be the result of dissection with subsequent fusiform degeneration of the artery, progressive enlargement, and luminal thrombosis or may be a consequence of intracranial atherosclerosis. These lesions are particularly challenging and often require indirect approaches for their obliteration compared to the standard direct clipping techniques most often used for saccular aneurysms.

Management principles

Standard intraoperative management is utilized. Intraoperative hypotension is avoided. In fact, intraoperative blood pressure is allowed to run mildly hypertensive, especially during temporary vessel clipping. For brain protection, all patients receive intravenous doses of barbiturates (pentobarbital) to achieve electroencephalographic burst suppression. As required, brain relaxation is achieved with hyperventilation, mannitol, barbiturates, or spinal drainage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Comprehensive electrophysiological monitoring is used routinely:7 somatosensory-evoked potentials, brainstem auditory responses (in both ears or the contralateral ear alone if ipsilateral hearing is to be sacrificed), and monitoring of the facial nerve and other appropriate CNs.

Surgical overview

The general principles for surgical treatment of aneurysms located in this part of the basilar artery are the same as those for any aneurysm.6,8–17 The main surgical difference relates to the anatomical considerations specific to the constrained aneurysm locations and the surrounding vital neuroanatomy. Regardless, the primary endpoint for the surgeon should be complete obliteration of the aneurysm from the circulation, with preservation of the parent vessels, particularly the perforators supplying the brainstem.

To achieve optimal aneurysm obliteration, maximal exposure of the basilar artery and the aneurysm itself is required. This exposure must be achieved without exposing the brain or critical structures to undue retraction while simultaneously obtaining adequate control of the parent vessel and aneurysm. Given the challenges of exposure in this region, specialized operative approaches are often necessary. In some cases, such approaches must be combined with the technique of hypothermic cardiac standstill.18–22 Alternatively, additional methods may be used for revascularization to allow proximal artery occlusion or trapping of the aneurysm.

Surgical decision making

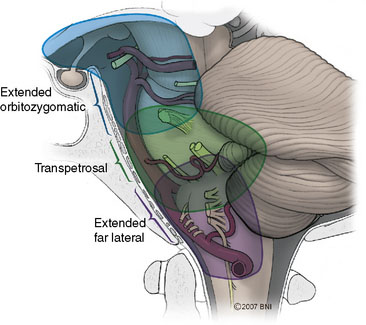

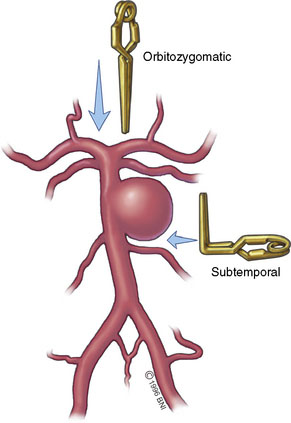

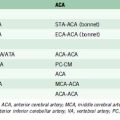

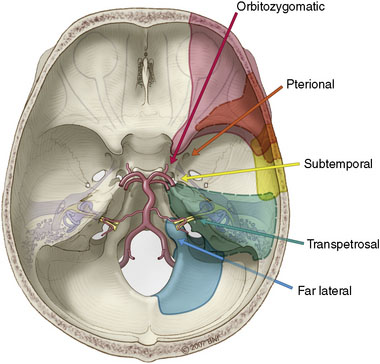

The various approaches that provide overlapping amounts of exposure can be seen in Figure 26–1. Typically, the subtemporal and orbitozygomatic approaches are used for basilar tip lesions, but the extended orbitozygomatic approach can provide access to the upper two-fifths of the basilar artery. Some aneurysms of the basilar trunk below the SCAs can be approached in this manner. The transpetrosal provides exposure further inferiorly, allowing the middle three-fifths of the basilar trunk to be accessed. With the combined supra- and infratentorial approach, access can be extended down to the vertebrobasilar junction. The far-lateral approach gives access primarily to the lower two-fifths of the basilar artery and is suitable for vertebrobasilar junction aneurysms. Both the far-lateral and extended orbitozygomatic approaches provide a view along the aneurysm neck, allowing a clip to be applied along this line of sight. In contrast, however, the transpetrosal approach exposes the aneurysm sac between the surgeon and the neck. A right-angled clip is required, increasing the technical difficulty of clip application (Figure 26–2).

Operative approaches

Next, the anatomical concerns specific to this region must be accommodated. In the past, these aneurysms were treated through a subtemporal-transtentorial approach or through the suboccipital approach. A transoral or transmaxillary-transclival approach has also been used,23 but exposure is limited and the risks of postoperative CSF leakage and meningitis are significant. Although these approaches can provide access to aneurysms of the mid- and lower-basilar artery, they seldom provide maximal exposure with minimal retraction. Consequently, the subtemporal and lateral suboccipital/retrosigmoid approaches are often superseded by more extensive skull base approaches that maximize lateral bone removal to provide a shorter and flatter route of access to the anterior brainstem and basilar artery (Figure 26–3). The basic tenets of these approaches and their application to mid- and lower-basilar artery aneurysms are reviewed.

Figure 26–3 Microsurgical corridors to the skull base and basilar artery.

(With permission from the Barrow Neurological Institute.)

Extended Orbitozygomatic Approach

The standard orbitozygomatic craniotomy, which has been well described for the management of tumors and aneurysms of the upper basilar artery,14,24–27 can be modified to allow access to the upper aspect of the midbasilar trunk.

Transpetrosal

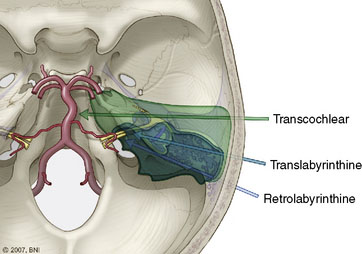

The transpetrosal approach encompasses a range of approaches with various extents of bony dissection that provide differential degrees of exposure to the anterior brainstem and clival region (Figure 26–4).28–30 Overall, this approach provides a lateral trajectory to the basilar trunk through a presigmoid corridor by drilling through the petrous aspect of the temporal bone. This approach can afford good proximal and distal control and is usually undertaken ipsilateral to the side of the aneurysm. The lateral angle of approach can place the aneurysm dome between the surgeon and the site of clip application at the neck of the aneurysm. However, a contralateral approach often mandates more complex clip strategies, including the use of fenestrated clips and a subsequent increase in the potential for perforator injury. The trajectory places the CNs in the foreground of the operative field, although this is true of all exposures to this region other than the direct anterior transoral or transclival.

Figure 26–4 Transpetrosal approaches to the basilar trunk.

(With permission from the Barrow Neurological Institute.)

The transpetrosal approach can be divided into three variations (see Figure 26–4): the retrolabyrinthine approach (which involves petrous bone resection between the semicircular canals anteriorly and the posterior fossa dura on the posterior aspect of the temporal bone). Hearing is preserved. The translabyrinthine approach removes more of the petrous bone (including the semicircular canals, thereby increasing exposure anteriorly to the internal auditory canal), and sacrifices hearing. The transcochlear approach involves maximal petrous bony resection by transposing the facial nerve posteriorly and allowing access for removal of the cochlea. Hearing is sacrificed and injury to the facial nerve is a risk. In each variation the amount of petrous bone resection increases with a resultant increase in exposure of the anterior brainstem and basilar trunk.

Revascularization

Although the primary surgical goal in the management of aneurysms is direct clip obliteration with preservation of the parent vessel, not all aneurysms are amenable to this approach.31–33 Large aneurysms especially can incorporate the parent vessel to such an extent that clip reconstruction is infeasible. The extreme example of this situation is fusiform vertebrobasilar dolichoectatic aneurysms or dissecting aneurysms, but even large saccular aneurysms can behave in this fashion. Under these circumstances, the remaining options are trapping of the aneurysmal segment or proximal occlusion to alter the flow dynamics in the region of the aneurysm to induce regression and spontaneous thrombosis.34,35

For mid- and lower-basilar lesions, direct trapping may be less desirable because of the potential risk to adjacent perforators.36 However, proximal or even distal basilar occlusion can serve to abolish the aneurysm effectively.37 For large fusiform dolichoectatic aneurysms, proximal occlusion of one or both vertebral arteries can reverse blood flow in a similar fashion by removing the hemodynamic wall stress thought to play a role in the growth of these degenerative lesions. If the caliber of the posterior communicating arteries is insufficient to provide adequate blood flow, this strategy must be combined with a bypass to the upper basilar territory. In such cases, the donor and recipient vessels depend on blood flow requirements and the availability of suitable vessels. For basilar trunk lesions, the distal basilar territory typically needs to be revascularized.38,39 Doing so can be accomplished with a STA donor or interposition graft from the external carotid artery anastomosed to the posterior cerebral artery or SCA. Posterior circulation bypasses tend to be technically demanding due to the depth at which the anastomosis must be performed. These procedures are associated with the general risks of any vascular surgery within the posterior circulation in addition to the more specific risks of graft failure and ischemia. In certain cases, however, revascularization and proximal occlusion strategy are the best feasible options.

Flow redirection

Flow-redirection techniques can be used for aneurysms involving the basilar artery.40 When an aneurysm cannot be removed from the circulation, the goal is to alter the hemodynamics at the lesion by changing the direction of blood flow. One approach involves a two-stage treatment paradigm. The first procedure consists of revascularization through an STA-SCA bypass, followed by a two-stage endovascular treatment. Another approach is unilateral occlusion of the vertebral artery proximal to the PICA, followed by contralateral vertebral artery occlusion distal to the PICA. The goal in delaying occlusion of the second vertebral artery is to provide the graft with time to mature. Ultimately, one PICA depends on back-flow from the basilar artery, and this demand is thought to help prevent basilar thrombosis, thus maintaining flow from the bypass to the basilar artery and the brainstem-perforating vessels.

1 Anson J.A., Lawton M.T., Spetzler R.F. Characteristics and surgical treatment of dolichoectatic and fusiform aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:185-193.

2 Higa T., Ujiie H., Kato K., et al. Basilar artery trunk saccular aneurysms: morphological characteristics and management. Neurosurg Rev. 2009;32:181-191.

3 Yamaura A., Ise H., Makino H. Treatment of aneurysms arising from the terminal portion of the basilar artery—with special reference to the radiometric study and accessibility of trans-sylvian approach. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1982;22:521-532.

4 Drake C.G., Peerless S.J. Giant fusiform intracranial aneurysms: review of 120 patients treated surgically from 1965 to 1992. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:141-162.

5 Peerless S.J., Nemoto S., Drake C.G. Acute surgery for ruptured posterior circulation aneurysms. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 1987;15:115-129.

6 Sanai N., Tarapore P., Lee A.C., et al. The current role of microsurgery for posterior circulation aneurysms: a selective approach in the endovascular era. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:1236-1249.

7 Quinones-Hinojosa A., Alam M., Lyon R., et al. Transcranial motor evoked potentials during basilar artery aneurysm surgery: technique application for 30 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:916-924.

8 Cantore G., Santoro A., Guidetti G., et al. Surgical treatment of giant intracranial aneurysms: current viewpoint. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(Suppl 2):279-289.

9 Fiorella D., Kelly M.E., Albuquerque F.C., et al. Curative reconstruction of a giant midbasilar trunk aneurysm with the pipeline embolization device. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:212-217.

10 Hassan T., Ezura M., Takahashi A. Treatment of giant fusiform aneurysms of the basilar trunk with intra-aneurysmal and basilar artery coil embolization. Surg Neurol. 2004;62:455-462.

11 Inamasu J., Suga S., Sato S., et al. Long-term outcome of 17 cases of large-giant posterior fossa aneurysm. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2000;102:65-71.

12 Kang H.S., Oh C.W., Han M.H., et al. Treatment of a sequential giant fusiform aneurysm of the basilar trunk. Korean J Radiol. 2005;6:125-129.

13 Kimura T., Onda K., Arai H. Multiple basilar artery trunk aneurysms associated with fibromuscular dysplasia. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2004;146:79-81.

14 Lawton M.T., Daspit C.P., Spetzler R.F. Technical aspects and recent trends in the management of large and giant midbasilar artery aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:513-520.

15 Ponce F.A., Albuquerque F.C., McDougall C.G., et al. Combined endovascular and microsurgical management of giant and complex unruptured aneurysms. Neurosurg Focus. 2004;17:E11.

16 Uda K., Murayama Y., Gobin Y.P., et al. Endovascular treatment of basilar artery trunk aneurysms with Guglielmi detachable coils: clinical experience with 41 aneurysms in 39 patients. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:624-632.

17 Van Rooij W.J., Sluzewski M., Menovsky T., et al. Coiling of saccular basilar trunk aneurysms. Neuroradiology. 2003;45:19-21.

18 Greene K.A., Marciano F.F., Hamilton M.G., et al. Cardiopulmonary bypass, hypothermic circulatory arrest and barbiturate cerebral protection for the treatment of giant vertebrobasilar aneurysms in children. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1994;21:124-133.

19 Kato Y., Sano H., Zhou J., et al. Deep hypothermia cardiopulmonary bypass and direct surgery of two large aneurysms at the vertebrobasilar junction. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1996;138:1057-1066.

20 Mack W.J., Ducruet A.F., Angevine P.D., et al. Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest for complex cerebral aneurysms: lessons learned. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:815-827.

21 Spetzler R.F., Hadley M.N., Rigamonti D., et al. Aneurysms of the basilar artery treated with circulatory arrest, hypothermia, and barbiturate cerebral protection. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:868-879.

22 Yu C.L., Tan P.P., Wu C.T., et al. Anesthesia with deep hypothermic circulatory arrest for giant basilar aneurysm surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Sin. 2000;38:47-51.

23 Saito I., Takahashi H., Joshita H., et al. Clipping of vertebro-basilar aneurysms by the transoral transclival approach. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1980;20:753-758.

24 Bambakidis N.C., Kakarla U.K., Kim L.J., et al. Evolution of surgical approaches in the treatment of petroclival meningiomas: a retrospective review. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(Suppl 3):1182-1191.

25 Hsu F.P., Clatterbuck R.E., Spetzler R.F. Orbitozygomatic approach to basilar apex aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(Suppl):172-177.

26 Lemole G.M.Jr, Henn J.S., Zabramski J.M., et al. Modifications to the orbitozygomatic approach. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:924-930.

27 Zabramski J.M., Kiris T., Sankhla S.K., et al. Orbitozygomatic craniotomy. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:336-341.

28 Inoue Y., Mikami J., Omiya N., et al. Subtemporal transpetrosal approach to ruptured midbasilar trunk aneurysm. Skull Base Surg. 1992;2:98-102.

29 Rosenberg S.I., Flamm E.S., Hoffer M.E., et al. The retrolabyrinthine transsigmoid approach to midbasilar artery aneurysms. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:100-104.

30 Terasaka S., Itamoto K., Houkin K. Basilar trunk aneurysm surgically treated with anterior petrosectomy and external carotid artery-to-posterior cerebral artery bypass: technical note. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:1083-1087.

31 Jafar J.J., Russell S.M., Woo H.H. Treatment of giant intracranial aneurysms with saphenous vein extracranial-to-intracranial bypass grafting: indications, operative technique, and results in 29 patients. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:138-144.

32 Lawton M.T., Hamilton M.G., Morcos J.J., et al. Revascularization and aneurysm surgery: current techniques, indications, and outcome. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:83-92.

33 Nabika S., Oki S., Migita K., et al. Dissecting basilar artery aneurysm growing during long-term follow up—case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2002;42:560-564.

34 Ewald C., Kuhne D., Hassler W. Giant basilar artery aneurysms incorporating the posterior cerebral artery: bypass surgery and coil occlusion—two case reports. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1998;38(Suppl):83-85.

35 Wenderoth J.D., Khangure M.S., Phatouros C.C., et al. Basilar trunk occlusion during endovascular treatment of giant and fusiform aneurysms of the basilar artery. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:1226-1229.

36 Ricolfi F., Decq P., Brugieres P., et al. Ruptured fusiform aneurysm of the superior third of the basilar artery associated with the absence of the midbasilar artery. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:961-965.

37 Ali M.J., Bendok B.R., Tella M.N., et al. Arterial reconstruction by direct surgical clipping of a basilar artery dissecting aneurysm after failed vertebral artery occlusion: technical case report and literature review. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:1475-1480.

38 Horie N., Kitagawa N., Morikawa M., et al. Giant thrombosed fusiform aneurysm at the basilar trunk successfully treated with endovascular coil occlusion following bypass surgery: a case report and review of the literature. Neurol Res. 2007;29:842-846.

39 Russell S.M., Post N., Jafar J.J. Revascularizing the upper basilar circulation with saphenous vein grafts: operative technique and lessons learned. Surg Neurol. 2006;66:285-297.

40 Amin-Hanjani S., Ogilvy C.S., Buonanno F.S., et al. Treatment of dissecting basilar artery aneurysm by flow reversal. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1997;139:44-51.