21 Body Work and Movement Therapies

Yoga

Yoga is an Indian art created by the sage Patanjali, approximately 2000 years ago to “see things as they really are and achieve freedom from suffering.”1 The details of the meditative program of yoga were chronicled in the Yoga sutra, written by Patanjali. A partly philosophical work, the sutra explores the nature and reason for human suffering and offers yoga as a potential remedy. Patanjali explains yoga as a vehicle for connecting with the external world, as well as for understanding the internal world. Despite the spiritual nature of yoga, the art is nonsectarian; traditionally, yoga was passed on directly from teacher to student.2

Asana, or posture, is the third limb. This limb consists of specifically designed physical postures that effectively stimulate the body (Fig. 21-1). Such postures are often named after the nature, mythological being, or body part they resemble, such as “the Lotus,” “Hanumanasana,” and “headstand,” respectively.3 The postures allow for the fourth limb, Pranayama, or breath control. The limb consists of a refined control of drawing air into the body and expelling it to expand what is known as Prana (life-force). Pratyahara, sensory inhibition, is the fifth limb. It involves managing the senses to allow the body to use them to look inward.

Figure 21-1 Modified child yoga position enhancing release of pelvic girdle and axial spine tension.

The next limb is Darana, or concentration. This limb involves steady concentration on a specific item without interruption. The seventh limb of yoga is Dhyana, meditation. Meditation is the ability to maintain one’s attention without being distracted. The final limb is Samadhi or ecstasy. This limb involves transcending oneself in all aspects and coming to understand ultimate truth.4

Yoga’s call for the specific control of body has allowed its’ practitioners to perform seemingly supernormal acts: “The voluntarily stopping and restarting of the heart, the holding of breath for extended periods, the ability to remain motionless for months or even years, and the prolongation of life itself are well-known examples.”5

Each Asana has its own respective benefits (Fig. 21-2). Four connected examples of Asanas include Sarvangasana, Halasana, Bhujangasana, and Matsyendrasana. Sarvangasana is the shoulder stand posture; it involves resting the body on the shoulders and neck. Generally, blood circulation is improved in this posture, allowing a large supply of blood to the upper extremities. In addition, the posture eliminates the stiffness caused by long periods of standing.

Halasana proceeds after Sarvangasana; the feet are positioned behind the head.6 This position completely stretches the spine and helps reduce constipation by increasing the movement of the intestines through compression. Bhujangasana is also known as the “cobra” posture and counteracts the forward bending of the previous two postures. Essentially, in this posture, the stomach lies to the ground with legs straight, while the neck is stretched backwards. As a result, the muscles of the neck are strengthened and the chest is stretched. Matsyendrasana continues the posture by allowing for the rotary flexion of the spine. In this Asana, the participant sits on the floor and brings the right heel against the perineum. The right hand then grasps the right knee, thereby allowing the body to twist. The lumbar muscles are stretched as a result of this position.7

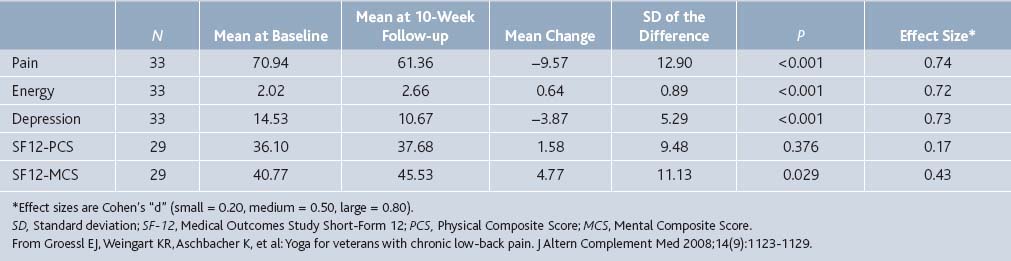

A recent article in the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine8 demonstrated the benefits of yoga on pain. Thirty-three veterans at the Veterans Administration Hospital in San Diego with chronic low back pain received weekly Anusara Yoga classes. After 10 weeks, the participants reported significant improvements in pain severity, with a mean rating of 70.94 out of 100 at baseline and 61.36 at follow-up (P < .001). There was also improvement on other parameters such as energy and depression (Table 21-1). Of note, these results reflect the thirty-three veterans who fully participated in the program, as 15 participants dropped out or were unavailable for follow-up after initial questionnaire.

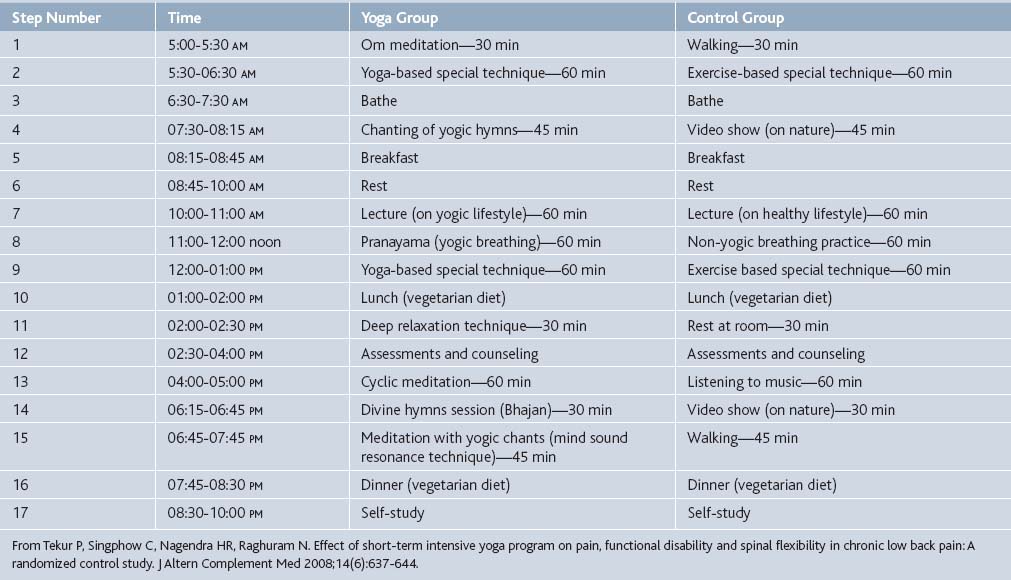

At the Swami Vivekananda Yoga Research Foundation in India a randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing the effect of a short-term intensive residential yoga program with physical exercise (control) on pain and spinal flexibility was conducted in subjects with chronic low-back pain.9 The intervention consisted of a 1-week intensive residential yoga program composed of Asanas designed for back pain, Pranayamas, meditation, and didactic and interactive sessions on philosophical concepts of yoga. The control group practiced physical exercises under a trained physiatrist and also had didactic and interactive sessions on lifestyle change. Hour-to-hour matching for the types of practices for the two groups was ensured (see Table 21-2). After 7 days, there was a significant reduction in pain scores (as measured by the Oswestry Disability Index) in the yoga group compared to the control group (P = .01; effect size 1.264).

In a pilot study of adults (mean age 59 years) with osteoarthritis of the knee where all participants received the intervention of yoga, Kolasinski and colleagues found statistically significant reductions in pain (a decrease of 47% over 8 weeks).10 The clinic-based intervention consisted of 90-minute sessions delivered weekly over an 8-week period. Of the 11 subjects enrolled, 7 (64%) completed at least five of the eight classes and underwent both pre- and postintervention assessments.

In an RCT conducted at West Virginia University School of Medicine, the investigators randomized 60 adults with chronic low back pain (mean age 48.3 years, low back pain for 11.2 ± 1.54 years) to weekly yoga classes (1.5 hours/week) or an education control group over 16 weeks.11 Pain was assessed using the Short Form-McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ).12 The SF-MPQ measures present pain intensity with a standard horizontal 10 cm visual analog scale (VAS)13 and the Present Pain Index (PPI). The VAS is a bipolar line scale with the descriptive anchors of no pain on the left side of the line and worst possible pain on the right side of the line. The PPI is a rating scale that requires each patient to endorse their pain with one check from 0 representing no pain to 5 representing excruciating pain. Forty-two (70%) subjects completed the study. At 3-month follow-up, the control group VAS rating was 2.0, whereas for the yoga group it was 0.6 (P = .039). The PPI rating was also significantly less in the yoga group than the control (0.5 versus 1.1, respectively, P = .013). Additionally, significantly more people in the yoga group stopped or decreased use of pain medication than the control group.

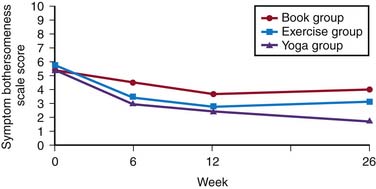

A study at the Group Health Cooperative,14 a nonprofit, integrated healthcare system in Washington and Idaho, enrolled 101 primary care patients (mean age, 44 years) with chronic back pain and randomized them to receive either 12 weeks of yoga, 12 weeks of a structured exercise class, or an education only group (participants were given a book on self-care for back pain). The participants were followed-up at 6, 12, and 26 weeks with a telephone interview and were asked, among other things, to rate from 0 to 10 how bothersome their pain had been during the previous week. All groups had decreased bothersome symptom scores at 26 weeks (see Fig. 21-3). No significant differences in bothersome symptoms were found between any two groups at 12 weeks; at 26 weeks, the yoga group was superior to the book group with respect to this measure (mean difference,− 2.2 [CI, −3.2 to −1.2]; P < .001), however there were no significant differences between the yoga and exercise groups.

Figure 21-3 Mean symptom bothersome symptom scale scores at baseline, 6, 12, and 26 weeks by treatment group.

(Adapted from: Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Erro J, et al: Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:849-856.)

At the University of Sao Paolo in Brazil 40 women with fibromyalgia were randomized to receive either relaxing yoga (RY) or relaxing yoga plus touch (RYT)—touch being the manipulative techniques of Tui Na.15 Both groups received weekly sessions for 8 weeks and showed improved pain scores. Touch addition yielded greater improvement during the treatment. Over time, however, RY patients reported less pain than RYT. These results suggest that a passive therapy may possibly decrease control over fibromyalgia symptoms.

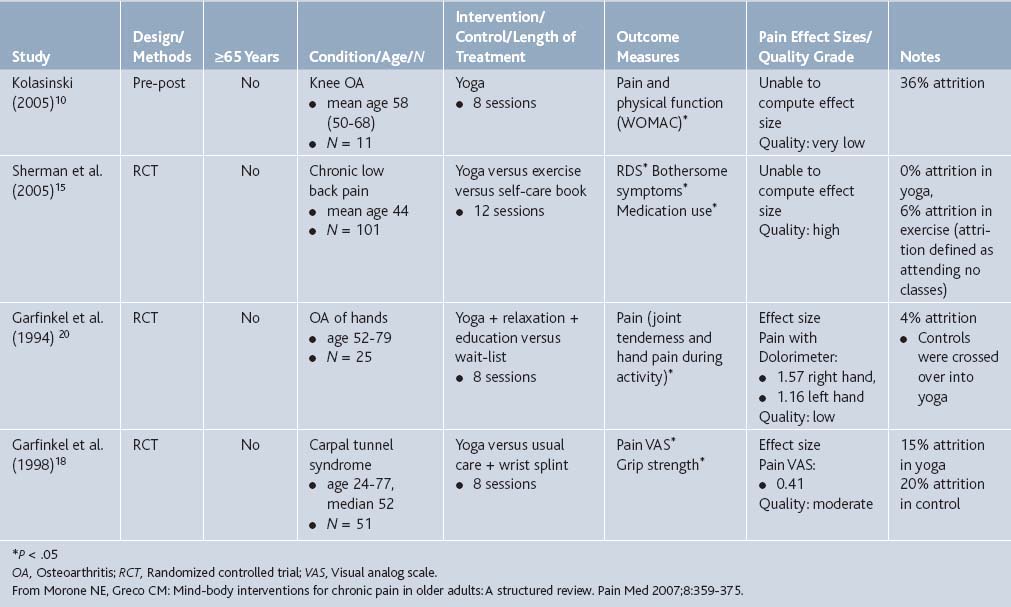

Morone and colleagues16 conducted a structured review of eight mind-body interventions for older adults with chronic nonmalignant pain. Of the articles that met criteria of studying older adults (>50 years) with chronic pain, they found that yoga was significantly associated with pain reduction for low back pain, osteoarthritis, and carpal tunnel syndrome. See Table 21-3 for summaries of the included studies.

Researchers at the University of Rajasthan17 examined yoga’s impact on migraine in an RCT. Seventy-two patients (mean age, 34, females > males) who had been diagnosed with migraine without aura were assigned to attend yoga or self-care groups for 12 weeks. After this time, the yoga group was statistically significantly less on all parameters measured (P < .001): headache frequency (4.56 versus 10.18 days in the last month), average pain score (4.64 versus 7.81 out of 10) and duration of attacks (4.78 versus 6.42 hours). Additionally, on the SF-MPQ pain questionnaire, the yoga group was significantly less in overall intensity of pain (1.69 versus 3.97).

Garfinkel and colleagues18 conducted a randomized controlled multicenter trial of Hatha Yoga for patients with carpal tunnel syndrome, emphasizing upper body postures and relaxation. The control group was assigned to wear wrist splints for 8 weeks. Participation in the yoga program was for 60 to 90 minutes, two times per week for 8 weeks. Average pain intensity in the subjects in the yoga group, as measured by the VAS, decreased from 5.0 to 2.9 after 8 weeks (P = .02), whereas pain did not significantly decrease in the control group. The authors of a follow-up article theorized that yoga may decrease wrist and hand pain by improving posture and reducing compression on the median nerve.19

Garfinkel also examined the effect of yoga on osteoarthritis pain.20 He conducted an RCT on patients with osteoarthritis who received either eight weeks of yoga (one 60-minute session per week focusing on stretching and strengthening of the upper body) or no therapy. The yoga-treated group improved significantly more than the control group in pain intensity during activity and tenderness.

In addition to musculoskeletal pain, yoga has been found to exhibit some relief in people with cancer pain. Researchers at Duke University21 conducted a pilot study of 21 women with metastatic breast cancer and who received the Yoga Awareness Program for 8 weeks. The Yoga Awareness Program was specifically designed for metastatic breast cancer patients and included gentle yoga postures, breathing exercises, meditation, didactic presentations, and group interchange. Lagged analyses of length of home yoga practice showed that on the day after a day during which women practiced more, they experienced significantly lower levels of pain.

Yoga is an effective treatment for pain as supported by a large body of literature; its benefits have been recognized by major medical societies. According to a report issued by the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society,22 yoga is a valid consideration for chronic or subacute low back pain in patients who have not improved with self-care options. This recommendation is largely based on the Group Health Cooperative study mentioned previously. The report grades the level of evidence as “Fair” with a moderate net benefit for Viniyoga, but “Poor” with unknown benefit for Hatha Yoga. It is unclear the mechanism by which yoga improves pain, but is likely due to a combination of stretching and physical movement with relaxation and mental focus. It is important to take note that several of these studies are confounded by noncompliance and drop-out. Yoga may relieve pain but only if those people with pain are able to and comply with practicing it.

Pilates

Pilates is a system of psychophysical exercise that was created by Joseph Pilates. It emphasizes good posture, proper breathing, body awareness, and graceful movement to better condition the body to prevent it from being prone to injury.23 Pilates was once associated with being the training method of the elite and famous. Since the 1980s, however, the training method has entered into the mainstream.

The history of Pilates began in the early 1900s while Joseph Pilates was interned in England with other German nationals. Originally working as a self-defense instructor for Scotland Yard, Pilates expanded and developed his ideas during his internment. In one particular case, he attached springs to hospital beds for immobile patients, allowing them to exercise. After the war, Pilates’ techniques become popular in the German dancing community. However, Pilates eventually decided to immigrate to the United States in 1926. By 1960, Pilates had married and worked as an instructor for ballerinas from the New York City Ballet. The popularity of his training expanded across the country. After Pilates’ death in 1967, his students, including Romana Kryzanowska, Ron Fletcher, Kathy Grant, and Lolita San Miguel, opened their own Pilates’ styled exercise studios around the country and in Puerto Rico. Notably, Ron Fletcher’s studio catered to Hollywood celebrities, greatly increasing the popularity of Pilates.24

The execution of Pilates varies depending on the equipment available as well as the aim of the user. Generally, mats and reformers, a system of springs and ropes for resistance, are most common. Variations of the exercise range from athletes who want a specific form of improvement, including running faster or throwing farther, to lay people looking to develop strength and coordination.25

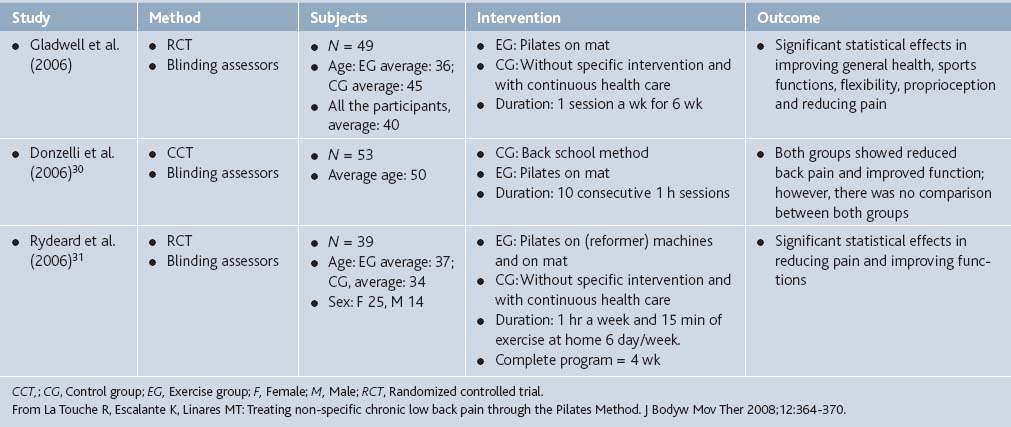

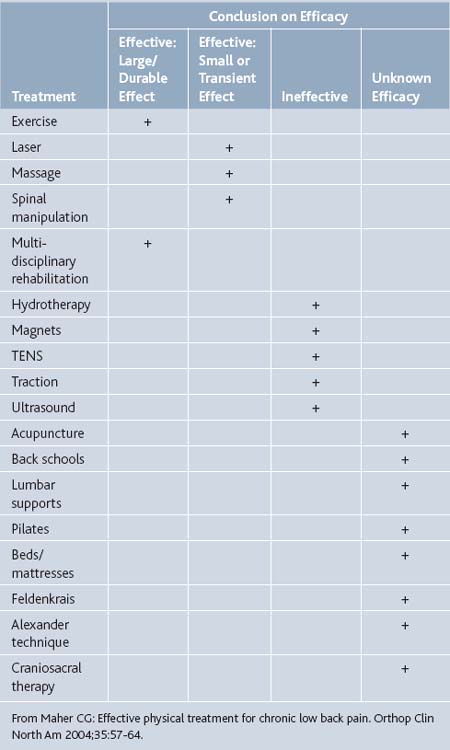

In Maher’s 2004 review,26 he concluded that there is insufficient scientific evidence to justify the effectiveness of Pilates (see Table 21-1). However, randomized clinical studies of the effect of Pilates on pain have become more common over the past few years, three of which were analyzed by La Touche and colleagues27 and deemed to be of satisfactory methodology (Table 21-4). The evaluation of the methodological quality of the studies was carried out using two instruments, the PEDro28 and Jadad Scales.29 The PEDro Scale includes 11 items to evaluate four fundamental methodological aspects of a study such as the random process, the blinding technique, group comparison, and the data-analysis process. All three controlled trials included in La Touche’s analysis indicated positive effects of Pilates for alleviating chronic lower back pain.

The Donzelli study30 (see Table 21-4), an RCT, showed significant reduction in back pain after daily therapy of Pilates or back school for 10 days. Pain was assessed using the Visual Analog Scale and decreased from an average score of 6 at pretreatment to 4 at 6-month follow-up. Although Pilates was not compared directly to back school treatment, the Pilates group showed better compliance and subjective response to treatment.

The Rydeard study (see Table 21-4),31 albeit small, had convincing results. After 4 weeks of Pilates practice, the posttest adjusted mean in lower back pain intensity in the specific-exercise-training group was 18.3 out of 101 (95% CI, 11.8 to 24.8), compared to 33.9 out of 101 (95% CI, 26.9 to 41.0) in the control group who received the usual care, defined as consultation with a physician and other specialists and healthcare professionals, as necessary (P = .002). After 12 months, however, there was no longer a significant difference in lower back pain between the two groups.

Beyond the aforementioned articles, there have been few other articles examining the effectiveness of Pilates in pain relief. A pilot study by Keays and colleagues32 evaluated four women with breast cancer status post-axillary dissection and radiation therapy. Each participant received 1-hour Pilates exercise sessions three times per week for 8 weeks. Pain was assessed using the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI),33 a 15-item, self-administered tool developed for use in patients with cancer. Results were inconclusive. Except for participant 1, high levels of pain at the study outset were not reported. Average pain level decreased by 2 to 11 points from baseline to intervention for participants 1, 3, and 4 but increased by 1 point for participant 2.

Massage

Massage is the stimulation of and applied pressure on soft tissue for therapeutic purposes, and is one of the oldest forms of medical treatment in the world, with origins in various societies. Chinese writings dating back to 2700 BC and 2598 BC mention massage in religious documents and a medical work, respectively. The depictions of massages were found on the wall of an Egyptian physician’s tomb in Saqqara circa 2330 BC. Massage was also mentioned and approved in both the Indian medical work, Ayurveda, written around 1800 BC and by Hippocrates in 400 BC in the book On Articulations.

Modern massage came into effect when the practice became more systematic. In 1863, the French publication of Estradere’s Du Massage, “systematically classified each massage technique according to the bodily system affected.” This influenced the rise of scientific massage techniques.34 Such techniques include the Swedish massage techniques developed by Per Henrik Ling in the early nineteenth century.

In the United States, modern scientific massage therapy was introduced in the mid 1800s. In the United States, massage techniques were used by physicians until the early 20th century. When the pharmaceutical revolution occurred in the 1940s, massage therapy became less acceptable and was categorized as an alternative form of health care. In the 1960s, physical therapy began to use massage for the treatment of musculoskeletal impairments and other physical impairments. During the same era, the growth in the movements toward emphasizing human psychology and spirituality greatly increased massage therapy’s popularity. Following the 1960s, massage therapy eventually became incorporated into the “normal,” healthy lifestyle. Nursing and physical therapy have come to reincorporate massage techniques including simple backrubs, reflexology, therapeutic touch, and aromatherapy massage. Presently, surveys in the United States have indicated the growing popularity of massage; it is one of the most commonly used therapies for both the general population as well as individuals with disabilities, and it is one of the top physician referrals for alternative therapies.35

Several common stroke techniques can be found among the myriad of massage techniques. These include, effleurage, friction, pressure, petrissage, vibration, and percussion. Effleurage involves rhythmic and gentle skin contact. Generally, the palm is used for larger body surfaces, whereas the fingers are used for smaller body surfaces. In the friction stroke technique, pressure is applied to one area with the thumbs or fingers in moderately. The pressure stroke is, similar to the friction stroke, except that pressure strokes are made with the hands. Petrissage, also known as kneading, involves lifting and holding skin and the underlying muscle. The tissues are pushed against the bone. Tissues are supported by one hand while kneading is done with the other hand. Kneading is generally limited to areas of the body with large muscles mass. Vibration strokes involve the use of continuous motion. For percussion strokes, the wrist is used for tapping areas of the body.36

Massage therapy to treat pain is extremely common in the United States, however, exact numbers are unclear. Sherman and others surveyed randomly selected acupuncturists, chiropractors, and massage therapists in two states.37 Back pain was the most common reason for visits to each of these providers, with chronic back pain representing about 12% of visits to massage therapists.

Wells and coworkers38 studied use of complementary and alternative therapies in 189 women with non–small-cell lung cancer. Massage was used by 6.9% of participants, most commonly for pain (54.8%). Women who were younger, experienced more symptoms, and lived on the West Coast or in the South (versus the Northeast) were more likely to use complementary and alternative therapies.

In a nationally representative survey that sampled 2055 adults, Wolsko and colleagues39 discovered that 54% of those reporting back or neck pain in the last 12 months used complementary and alternative therapies, including 14% who used MT. According to Brett and colleagues, 15% of midlife U.S. women have used massage and chiropractic medicine, most commonly for pain.40 Palinkas and Kabongo41 surveyed 542 patients attending sixteen family practice clinics belonging to a community-based research network in San Diego, California, and found that 17.2% used MT. The results of a survey and interviews of older adults showed that the most prevalent motivation for using complementary and alternative therapies was pain relief (54.8%), and that MT was used by 35.7%.42 Prevalence of MT use in a large military family practice clinic was found to be 36%, most commonly used for back or other musculoskeletal pain.43

In a telephone interview survey of Chicago adults 45 years of age or more, Feinglass and others44 discovered that more than half of the respondents used complementary and alternative therapies, most commonly MT and relaxation techniques. Similarly, more than half of traumatically injured spinal cord patients with shoulder pain received MT or physical therapy.45

In terms of the benefits of massage, Ernst evaluated systematic reviews of massage therapy (MT) and chiropractic effects on reduction of any type of pain.46 Two reviews were found, and there was not unequivocal evidence for effectiveness of MT in controlling musculoskeletal or other pain. A meta-analysis of 37 studies that used random assignment concluded that single applications of MT did not reduce immediate assessment of pain, whereas multiple applications reduced delayed assessment of pain.47

Back and colleagues described a pilot program to evaluate the efficacy of employer-funded on-site massage therapy on job satisfaction, workplace stress, pain, and discomfort.48 Twenty-minute massage therapy sessions were provided weekly for 4 weeks. Evaluation demonstrated possible improvements in job satisfaction, with initial benefits in pain severity (as measured by the Brief Pain Inventory49), and the greatest benefit for individuals with preexisting symptoms. Pain severity decreased by about 2% when initially measured after the 4-week massage period. However, at follow-up of 6 weeks and 12 weeks, pain severity actually incrementally increased. This was thought to be due to the MT making participants more aware of their bodies and pain, thereby causing them to report higher pain scores.

Use of MT in neck, back, and other musculoskeletal pain has been studied extensively. A review by Trinh and others50 concluded that there is limited evidence that MT is less effective than acupuncture in chronic mechanical neck pain. Ezzo and colleagues51 analyzed 19 trials of MT in neck pain, with 12 of 19 receiving low-quality scores. Descriptions of the massage intervention, massage professional’s credentials, or experience were frequently missing. Six trials examined massage as a stand-alone treatment. The results were inconclusive. Results were also inconclusive in 14 trials that used massage as part of a multimodal intervention because none were designed such that the relative contribution of massage could be determined.

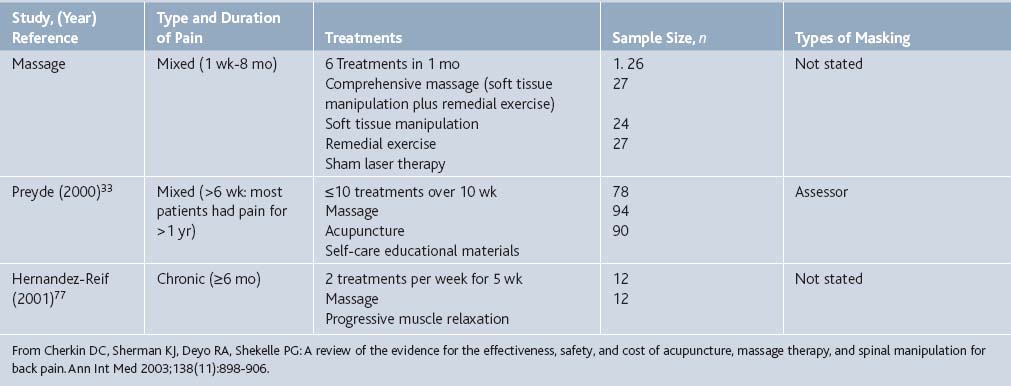

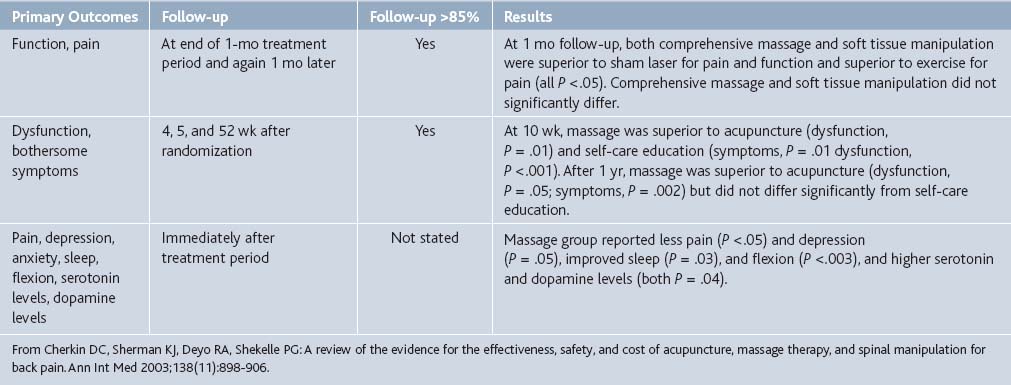

Cherkin and co-authors52 reviewed Medline, Embase, and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, and included three RCTs that evaluated massage and reported that this therapy is effective for subacute and chronic back pain and superior to certain other therapies (Tables 21-5 and 21-6). For example, Hernandez-Reif compared massage therapy to muscle relaxation. Twelve patients with chronic low back pain were randomly assigned to each of these treatments. After ten 30-minute sessions over 5 weeks, massage was found to be superior to progressive muscle relaxation for pain, depression, flexion, and sleep.

Similarly, Furlan and colleagues53 conducted a systematic review of Medline, Embase, Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, HealthSTAR, CINAHL, and dissertation abstracts describing use of MT for lower back pain. Nine publications reporting on eight randomized trials were included. Three had low and five had high methodological quality scores. Massage was compared with an inert treatment (sham laser) in one study that demonstrated massage was superior, especially if given in combination with exercises and education. In the other seven studies, massage was compared with different active treatments. They showed that massage was inferior to manipulation and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; massage was equal to corsets and exercises; and massage was superior to relaxation therapy, acupuncture, and self-care education. The beneficial effects of massage in patients with chronic LBP lasted at least 1 year after the end of the treatment. One study comparing two different techniques of massage concluded in favor of acupuncture massage over classic (Swedish) massage.

A review of several modalities including MT in the management of painful musculoskeletal disorders54 concluded that, although evidence from basic science research suggests many of the therapies could have potentially therapeutic effects, there is limited high-quality evidence from randomized clinical trials to support the therapeutic effectiveness of these therapies.

Best and colleagues reviewed evidence for using massage for muscle and soft tissue pain and weakness after intense exercise.55 Analysis of 27 studies that met inclusion criteria led authors to conclude that, although case series provide little support for the use of massage to aid muscle recovery or performance after intense exercise, randomized controlled trials provide moderate data supporting its use to facilitate recovery from repetitive muscular contractions. It also appears that the experience of the massage therapist may be directly related to effectiveness of the MT in relieving muscle soreness after a 10 km race.56

Dryden and associates57 reviewed evidence for using massage in orthopedic problems and concluded that massage therapy may be effective for orthopedic patients with low back problems and potentially beneficial for patients with other orthopedic problems. Massage therapy appears to be safe, to have high patient satisfaction, and to reduce pain and dysfunction. In a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial of 140 subjects with knee osteoarthritis, physiotherapy including MT appeared no more effective in reducing pain at 12 and 24 weeks than regular contact with a therapist.58

Several investigators have studied use of massage in cancer pain. Ferrell-Torry and Glick59 administered thirty minutes of therapeutic massage on two consecutive evenings to nine hospitalized males diagnosed with cancer and experiencing cancer pain. Massage therapy significantly reduced the subjects‘ level of pain perception and anxiety. In addition to these subjective measures, all physiologic measures (heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure) tended to decrease from baseline, providing further indication of relaxation. Building on the work of these authors, Grealish and colleagues60 administered 10-minute foot massage (5 minutes per foot) to 87 subjects hospitalized with cancer and found a significant immediate effect on the perceptions of pain, nausea, and relaxation when measured with a visual analog scale.

In a larger study, the impact of a Swedish massage intervention on 251 oncology in-patients‘ (mean age, 54.96) perceived level of distress.61 The analysis found a statistically significant reduction in patient-reported distress for both pain and physical discomfort by 43% and 47%, respectively, regardless of gender, age, ethnicity, or cancer type (P = .000).

Jane and colleagues62 reviewed 15 studies published in English between 1986 and 2006 for study design, methods, and massage efficacy in adult patients with cancer. Methodological issues identified included less rigorous inclusion criteria, failure to consider potential confounding variables, less than rigorous research designs, inconsistent massage doses and protocols, measurement errors related to sensitivity of instruments and timing of measurements, and inadequate statistical power. Use of massage by caregivers during cancer treatment in children has also been reported.63

There is a distinct body of literature describing the use of MT in puerperal and neonatal periods. Several investigators agree that massage is effective in reducing low back and labor pain, particularly during early stages of labor.64–66 Additionally, it appears that perineal massage during labor may prevent third-degree but not first- and second-degree perineal tears.67

Sensorial saturation including massage was studied by Bellieni and co-authors, and found to be an effective analgesic technique during minor painful procedures on newborns.68 Experience of the provider did not seem to make a difference.69

Use of massage for post-operative pain control has been addressed by several authors. Forchuk and colleagues70 evaluated the usefulness of arm massage from a significant other following lymph node dissection surgery in a randomized clinical trial that included 59 women. Participants reported a reduction in pain in the immediate postoperative period and better shoulder function. Anderson and Cutshall71 reviewed benefits of massage in the reduction of pain, anxiety, and tension in cardiac surgical patients and described a clinical case example of a patient who has experienced cardiac surgery and received massage therapy[M5]. He complained of persistent pain in the sternum, shoulder, and back following surgery despite increased doses of pain medication. After a 20-minute massage session, the patient reported his pain decreased from 7 to 2 on the VAS. The authors argue that MT can serve as a postsurgical pain blocker by modulating pain transmission in nerves. It may activate impulses in larger diameter nonpain fibers that block transmission in smaller diameter pain-fibers that travel to the spinal cord. This is based on Melzack and Wall’s gate-control theory of pain.72

In a study attempting to test the effectiveness of physiotherapy-based rehabilitation starting 1 week after lumbar disc surgery, Erdogmus and co-authors73 compared “comprehensive” physiotherapy, “sham” neck massage, and no therapy. Low back pain at 12 weeks was equally improved in the comprehensive and the sham massage groups, compared to controls.

In a randomized trial of MT in 605 veterans with acute postoperative pain after major surgery, Mitchinson and others74 found that compared with the control group, patients in the massage group experienced short-term decreases in pain intensity (P = .001), pain unpleasantness (P < .001), and anxiety (P = .007). In addition, patients in the massage group experienced a faster rate of decrease in pain intensity (P = .02) and unpleasantness (P = .01) during the first 4 postoperative days compared with the control group.

Another area that deserves discussion is use of massage in patients with pain related to burn injuries. Field and colleagues75 randomly assigned 28 adult patients with burns before débridement to either a massage therapy group or a standard treatment control group. Massage therapy group demonstrated decreased pain on the McGill Pain Questionnaire, Present Pain Intensity scale, and Visual Analog Scale.

In their review, Gallagher and colleagues76 described massage as one of the nonpharmacologic modalities routinely used in treating patients with burns. Hernandez-Reif and others77 studied 24 young children (mean age, 2.5 years) hospitalized for severe burns who received standard dressing care or massage therapy in addition to standard dressing care prior to dressing changes. The massage therapy was conducted on body parts that were not burned. During the dressing change, the children who received massage therapy showed minimal distress behaviors and no increase in movement other than torso movement. In contrast, the children who did not receive massage therapy responded to the dressing change procedure with increased facial grimacing, torso movement, crying, leg movement, and reaching out. Nurses also reported greater ease in completing the dressing change procedure for the children in the massage therapy group.

Schneider and colleagues78 described massage as a common alleviating factor in their review of neuropathic-like pain after burn injury.

Overall, it seems that massage therapy has a beneficial effect in a variety of types and contexts of pain. It should be considered by physicians as an alternative or complementary therapy to conventional pain management techniques. Of course, the skills and training of massage therapists vary widely and it is imperative that patients and their doctors take great care when choosing a practitioner.

Tai Chi

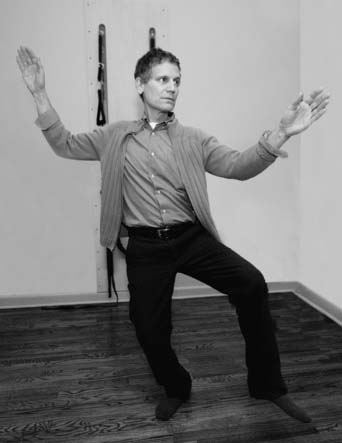

Tai Chi Chuan is a martial art rooted in the philosophy of Daoism that emphasizes fluid, continuous movement (Fig. 21-4). Literally translated as the “supreme ultimate fist,”79 Tai Chi Chuan strives for balance and harmony in the practitioners’ movements vis-à-vis Chi or Qi, the metaphysical life force that Daoism believes to run through all living beings. Through the correct positioning of the body, the gracefully proper transitions between positions, as well as mental concentration, Tai Chi Chuan aims for harmony within the practitioner and between the practitioner and way of nature (Fig. 21-5). Because the emphasis of Tai Chi Chuan is precise and fluid motion, it can be practiced by a wide range of age groups.80

The way of nature is a fundamental aspect of both Daoism and Tai Chi Chuan. The quintessential book of Daoism, the Dao De Jing, states that the Dao has no set form but can be understood through the cyclical movement of nature as well as through the opposite, yet complementary forces in nature.81 The Dao has been described as being, “like empty space, but emptiness has been undervalued, since the hollow in the center of a bowl, the space in a wheel between rim and hub, or the empty space of a window or door in a room are the very things which give these objects their point and usefulness.” In essence, the passiveness of the Dao helps the flow of Chi in the body.82

The recorded history of Tai Chi Chuan begins in the 17th century, a transition period between the Ming and Qing dynasties. The art of Tai Chi Chuan was a secret and closely protected heirloom of the Chen family. This pattern was broken around the 19th century when Yang Luchan, the first notably nonmember of the Chen family, learned the art from Chen Changxing. Eventually Yang made his own contributions to the art, leading to the creation of the Yang style. Proliferation of Tai Chi Chuan continued and as a result, multiple variations of Tai Chi Chuan exist today, with the Chen, Yang, Sun, Wu, and alternative Wu, as the more popular of the variations.83

From these principles, the actual practice of Tai Chi Chuan begins with warm-up exercises such as foot massages and gentle patting of the face, neck and arms; this is done to stimulate the movement of chi. The final part of the warm-up involves the “waving arms” exercise; the exercise involves shifting the body weight among the legs and other parts of the body as well as free swinging of the arms in a backwards motion. After the warm-up, the exercises begin. Common to all the variations of Tai Chi Chuan is the review. At the beginning of each session, previous motions are reviewed to ensure they have been practiced adequately and that the motions are correct. Typically, a session lasts between 60 to 90 minutes in length.85

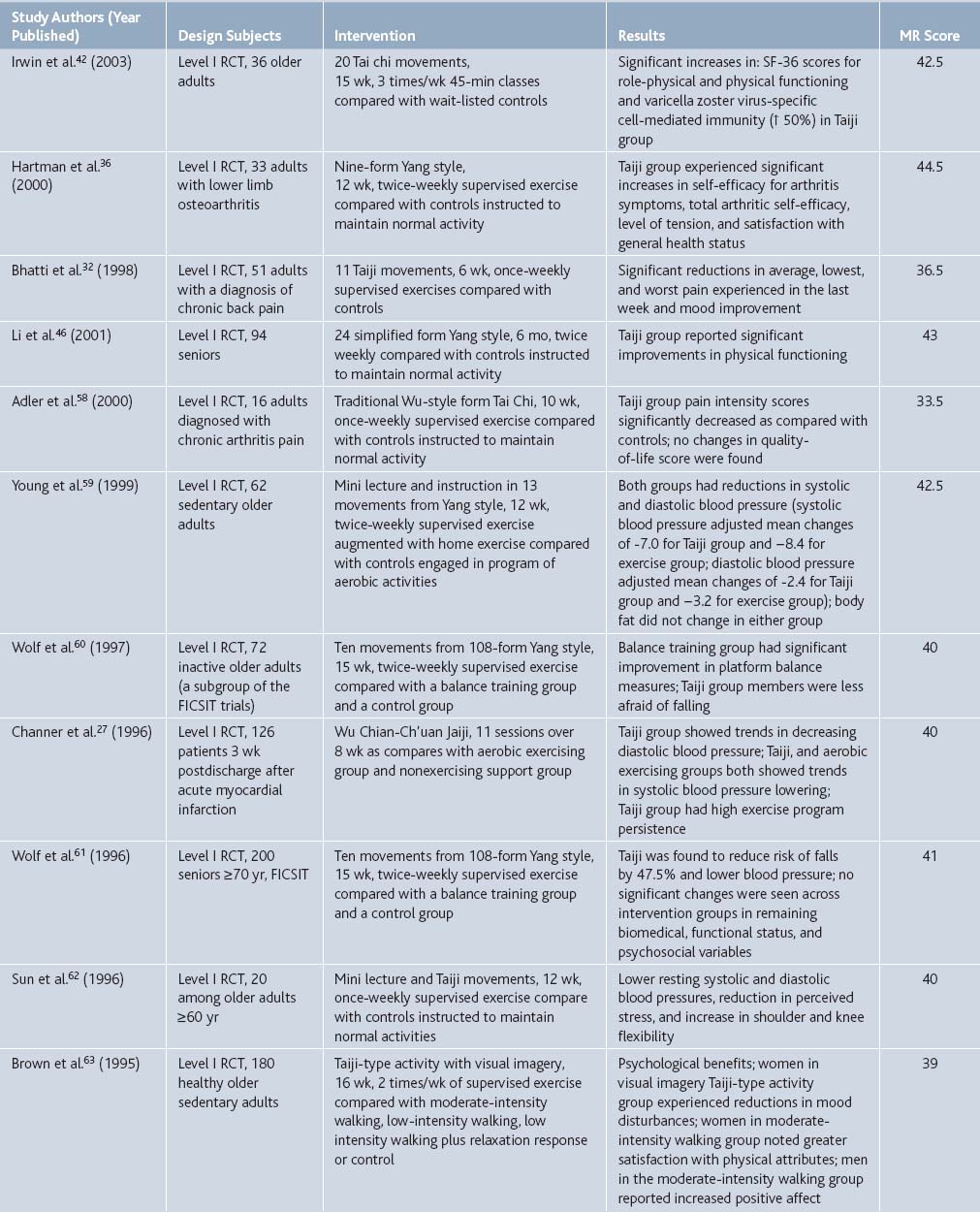

Comprehensive benefits of Tai Chi were reviewed by Klein and Adams.86 Of more than 200 published reports examined, 17 controlled clinical trials were judged to meet a high standard of methodological rigor. Controlled research evidence was found to confirm therapeutic benefits of Tai Chi practice with regard to pain management (Table 21-7).

Table 21-7 Synopsis of Level I and Level II Evidence Investigating Therapeutic Benefits of Taiji By Research Design, Subject, Intervention, Salient Findings, and Score for Methodologic Rigor (MR)

Use of Tai Chi among other mind-body interventions in neurology patients was reviewed by Wahbeh and others.87 Authors discussed applications of mind-body therapy to general pain, back and neck pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, headaches, and fibromyalgia, and concluded that the evidence for the efficacy of mind-body therapies is quite strong in some conditions, such as migraine headache.

Research-based use of Tai Chi for reducing pain and stress as a potential nursing intervention was summarized by Chen and Snyder.88 Authors critically evaluated existing literature and suggested that additional studies about the effects of Tai Chi from a nursing perspective are needed to make clear when it is beneficial as a nursing intervention.

Conversely, Siu and and coworkers89 used Tai Chi as a control intervention in a study evaluating a 6-week Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) in 148 subjects with chronic illness. CDSMP subjects used more cognitive methods to manage pain and had a tendency to adopt the cognitive methods of diverting attention, reinterpreting pain, ignoring sensations, and making positive self-statements, when compared with subjects assigned to the Tai Chi (control) group.

A number of investigators studied the effectiveness of Tai Chi in patients with osteoarthritis pain. Lee and colleagues90 conducted a systematic review of use of Tai Chi for osteoarthritis. Authors conducted systematic searches on Medline, AMED, British Nursing Index, CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, The Cochrane Library 2007, Issue 2, the UK National Research Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, Korean medical databases, the Qigong and Energy database and Chinese medical databases (until June 2007). Hand searches included conference proceedings and the authors‘ own files. Five RCTs assessed the effectiveness of Tai Chi on pain of osteoarthritis. Two RCTs suggested significant pain reduction on VAS or Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) compared to routine treatment and an attention control program in knee osteoarthritis. Three RCTs did not report significant pain reduction on multiple pain sites.

In a prospective, pretest-posttest clinical trial, Shen and colleagues91 examined the effects of Tai Chi exercise on gait kinematics, physical function, pain, and pain self-efficacy in elderly with knee osteoarthritis. After 6 weeks of Tai Chi exercise, knee pain was significantly decreased (P = .002), whereas no change was observed in pain self-efficacy.

Lee and Lee92 studied effects of Tai Chi exercise on pain and stiffness of knee joint in forty-six community-dwelling elderly subjects with osteoarthritis. The experimental group had significantly less pain (P = .008) and stiffness (P = .003) than the control group.

Wang and colleagues93 discuss the challenges of designing an RCT with long-term follow up. Their RCT examines the effects of a 12-week Tai Chi program compared with an attention control (wellness education and stretching) on pain, functional capacity, psychosocial variables, joint proprioception, and health status in elderly people with knee osteoarthritis and is expected to be completed by July 2009. The challenges encountered by the authors included strategies for recruitment, avoidance of selection bias, the actual practice of Tai Chi, and the maximization of adherence and follow-up while conducting the clinical trial for the evaluation of the effectiveness of Tai Chi on knee osteoarthritis.

Two studies examined comparative efficacy of hydrotherapy and Tai Chi in patients with osteoarthritis. Lee94 compared the effects of Tai Chi, aquatic exercise, and a self-help program in 50 patients. There were significant differences in joint pain (P = .000) and stiffness (P = .001) for both the Tai Chi and the aquatic exercise groups compared to the self-help group.

In a larger RCT, Fransen and colleagues95 randomly allocated 152 older persons with chronic symptomatic hip or knee OA for 12 weeks to hydrotherapy classes, Tai Chi classes, or a waiting list control group. Outcomes were assessed 12 and 24 weeks after randomization and included pain and physical function (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index). At 12 weeks, compared with controls, participants allocated to hydrotherapy classes and Tai Chi classes demonstrated significant improvements for pain scores. All significant improvements were sustained at 24 weeks. Interestingly, class attendance was higher for hydrotherapy, with 81% attending at least half of the available 24 classes, compared with 61% for Tai Chi. Similarly, while demonstrating significant pain reduction in the Tai Chi group, the drop-out rate in the study by Song and others96 was 41%.

In contrast to the findings of Fransen and colleagues, Brismee and associates97 found that although 6 weeks of group Tai Chi followed by another 6 weeks of home Tai Chi training resulted in significant improvements in mean overall knee pain (P = .0078) and maximum knee pain (P = .0035) compared to controls, all improvements disappeared after “detraining” at 18 weeks.

Several studies investigated using Tai Chi in pain associated with rheumatoid arthritis.

Han and colleagues98 attempted to assess the effectiveness and safety of Tai Chi as a treatment for people with rheumatoid arthritis. These authors searched the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, Medline, PEDro and CINAHL databases, the Chinese Biomedical Database and the Beijing Chinese Academy of Traditional Medicine. RCTs and controlled clinical trials examining the benefits and harms of exercise programs with Tai Chi instruction or incorporating principles of Tai Chi philosophy were selected for review and included four trials including 206 participants. Although the included studies did not assess the effects on patient-reported pain, the results suggest Tai Chi does not exacerbate symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis.

Yocum and colleagues99 reviewed the role of exercise, education, and behavioral modification as alternative therapy for pain and stress in rheumatoid arthritis. Their analysis indicated that programs using alternative therapies such as Tai Chi in combination with traditional medications appear to be beneficial for patients with arthritis, and that these individuals appear to live better lives and may have better long-term outcomes[M8]. They argue that methods such as Tai Chi relieve stress and alter endocrine and immune system functions in ways that relieve rheumatoid arthritis pain.

A systematic review of Medline, PubMed, AMED, British Nursing Index, CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, The Cochrane Library, the UK National Research Register and ClinicalTrials.gov, Korean medical databases, Qigong and Energy Medicine Database, and Chinese databases identified two RCTs that assessed pain outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who performed Tai Chi. The trials did not demonstrate effectiveness on pain reduction compared with education plus stretching exercise and usual activity control.100

Yet, in a controlled trial of 61 subjects with rheumatoid arthritis, Lee and Jeong101 found that pain and fatigue significantly decreased in the experimental group[M9].

Koh describes his personal experience with using Tai Chi for symptoms of ankylosing spondylitis that are unresponsive to conventional therapies.102 After 2½ years of daily practice the author felt less pain in addition to other positive results. However, pain returned if practice was neglected for as little as 1 week.

There were also several studies examining effects of Tai Chi on pain in college students and the elderly. Wang and coworkers103,104 administered a 3-month intervention of Tai Chi exercise to college students, and multidimensional physical and mental health scores including bodily pain were assessed using the SF-36 health survey questionnaire before and after the intervention. Bodily pain improved significantly after Tai Chi exercise intervention.

Reid and colleagues105 reviewed the evidence regarding self-management interventions for pain due to musculoskeletal disorders among older adults. After searching the Medline and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature databases, authors identified 27 articles that evaluated programs including yoga, massage therapy, Tai Chi, and music therapy. Positive outcomes were found in 96% of the studies. Proportionate change in pain scores ranged from an increase of 18% to a reduction of 85% (median, 23% reduction). Generalizability issues identified included limited enrollment of ethnic minority elders, as well as nonethnic elders aged 80 and older.

Another review, conducted by Morone and Greco,106 found limited support for meditation and Tai Chi for improving function or coping in older adults with low back pain or osteoarthritis. Several studies included older adults, but did not analyze benefits by age. Tai Chi, yoga, hypnosis, and progressive muscle relaxation were significantly associated with pain reduction in these studies. Ross and others107 evaluated effects of Tai Chi exercise on 11 elderly women. Findings included significant improvement (P = .05) in pain perception as measured by the Visual Analog Scale. Ho and colleagues compared health-related quality of life in 140 elderly practicing Tai Chi and 560 age- and sex-matched control subjects taken from the general population.108 Authors found no significant difference in the bodily pain scales between Tai Chi and control groups.

Despite these findings, in a larger study using similar design, Kin and associates109 found that when the 804 elderly participants were further subdivided in age cohorts, the 70- to 80-year old subjects practicing Tai Chi had significantly better bodily pain scores (P < .05) than the age- and sex-matched national average.

Finally, in a fascinating study involving 112 healthy older adults aged 59 to 86, Irwin and colleagues110 set out to evaluate the effects of Tai Chi on resting and vaccine-stimulated levels of cell-mediated immunity (CMI) to varicella zoster virus (VZV) and on health functioning in older adults. In a prospective, RCT, the subjects were vaccinated with the live attenuated VZV vaccine licensed to prevent varicella. The Tai Chi group showed significant improvements in SF-36 scores for bodily pain, vitality, and mental health (P < .05).

Alexander Technique

Alexander technique is a methodology for the treatment of chronic illness or conditions due to stress. Although it does not cure any of the conditions, Alexander technique does manage to make the condition less taxing on the afflicted individual. In general, the technique works through psychosensory education; the afflicted individuals are taught by teachers of Alexander technique to identify habits that may be the cause of unnecessary and extra discomfort. Interestingly, Alexander technique does not involve any exercises or forms of meditation; it is essentially a system of self-analysis and eventually, one of self-care.111

The origin of Alexander technique is rooted in the personal experiences of Frederick Matthias Alexander. Born in 1869, he eventually became a Shakespearian recitalist at age 19. However, he experienced recurring laryngitis. The medical help he sought was unable to identify the cause of his condition.112 One day, however, Alexander began to question how he used his voice. Eventually, realized that whenever he would go on stage, his body would produce an unconscious response; his body would tighten up. At first, he attempted to correct his problem by “standing straight,” but this only managed to worsen his condition. Alexander managed to overcome his problem by being consciously aware of himself while he spoke. He discovered that by doing so, he could release the tension in his body and be more relaxed while he spoke. The key to his method rests in the focus of the moment, or having active sensory awareness, rather than focusing on the product, the outcome of the moment.113

The notion of posture was also addressed by the Alexander technique. According to Alexander, the spine naturally lengthens as an individuals becomes aware of their own movements, thereby maximizing the comfort of the body. When an individual forces himself or herself to follow an idea of posture, the body cannot naturally assume it because of the mind’s influence. Therefore, Alexander believed that “poise”, a term associated with plasticity, would more be a more appropriate word than “posture”, a static word.114

In practice, the Alexander technique involves a one-to-one lesson between the student and the teacher, in which the teacher aids the student in identifying his or her own unwanted tensions and reactions, allowing the student to eventually develop self-care. The teachers of Alexander technique emphasize everyday activities, which include reading, sitting, lying down, and so on. By doing so, the student goes through each of the Alexander technique stages: “the means-whereby (conscious awareness in action) and nonendgaining (process over product), inhibition (nondoing, noninterference), and direction (carrying out clear intention to move).”115

The Alexander technique generally applies to individuals with neurologic and musculoskeletal problems. Typical afflictions and conditions that Alexander technique can help include pain management, chronic fatigue syndrome, disc herniation, sciatica, osteoporosis, stenosis, occupational injuries, and strains of musicians, dancers, computer workers, and singers.116

In Maher’s 2004 article117 analyzing scientific evidence for various physical treatments of low back pain, he groups the Alexander technique with other therapies of “unknown efficacy” (see Table 21-8) given the paucity of high-quality clinical trials evaluating it.

Alexander technique has been shown to be effective when it is part of a multidisciplinary approach to chronic lower back pain.118 Elkayam and colleagues in Israel found significant reductions in pain after a 4-week program of back school, psychological intervention, chiropractic manipulation, Alexander technique, and acupuncture. Using the VAS, pain ratings dropped from a mean of 7.02 to 4.67 (P < .01) and was maintained for 6 months following treatment. Yet the researchers did not identify the contributions of the different modalities and, thus, no conclusions can be made about any of them individually.

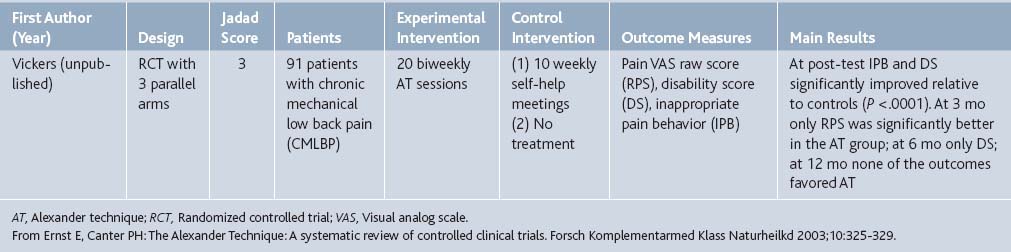

Researchers in the United Kingdom119 performed a systematic review of controlled, clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of the Alexander technique. In their search of Medline, Embase, Amed, CSICOM, and Cochrane Library, as well as material from experts in the field, two trials were methodologically sound and clinically relevant. One of those addresses pain, an unpublished trial by Vickers of patients with chronic mechanical low back pain (Table 21-9). When compared to controls who received weekly self-help meetings, there seemed to be pain improvement in the experimental group at 3-month follow-up.

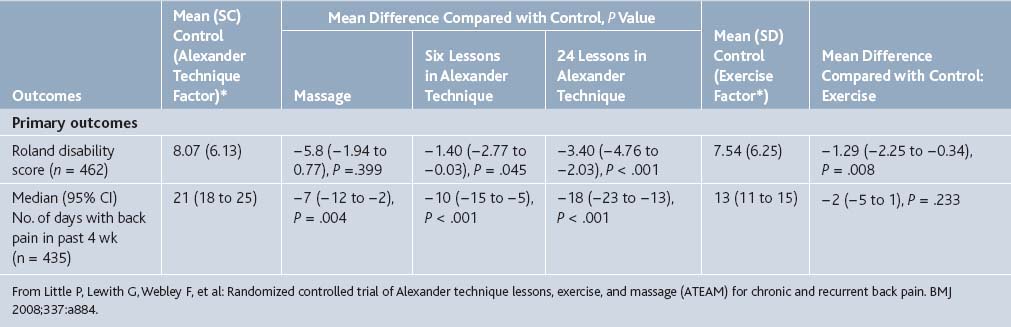

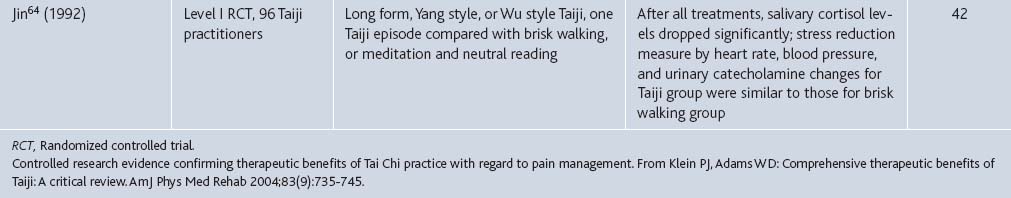

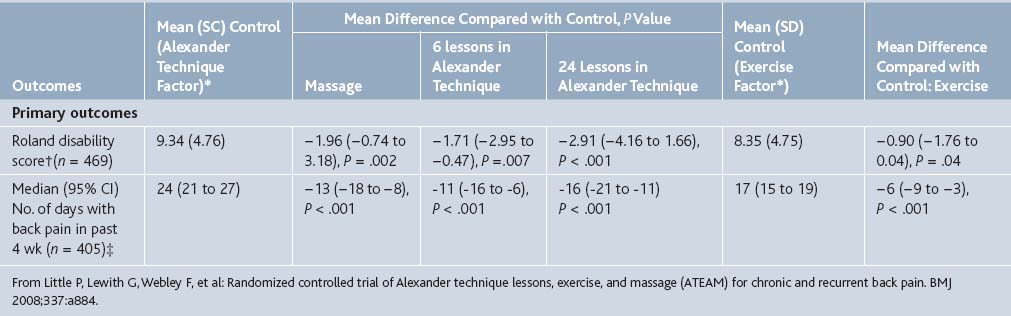

However, more recently Little and colleagues120 reported the results of an RCT to determine the effectiveness of Alexander technique lessons, exercise, and massage for chronic and recurrent back pain. The 579 participants in the trial (average age 45 years) reported an average of 279 days of pain in the past year (SD 131). The participants were assigned to receive either normal care (control), 6 sessions of massage, or 6 or 24 lessons on the Alexander technique. Half of the patients in each of these groups also received a prescription for exercise from a doctor as well as behavioral counseling from a nurse (Table 21-10).

Table 21-10 Trial Groups for Patients with Chronic or Recurrent Back Pain

| Intervention | No Exercise | Exercise∗ |

|---|---|---|

| Normal care | Group 1 (control) | Group 5 |

| Therapeutic massage (six sessions)† | Group 2 | Group 6 |

| Alexander technique lessons (n = 6)‡ | Group 3 | Group 7 |

| Alexander technique lessons (n = 24)§ | Group 4 | Group 8 |

∗ Doctor prescription and up to three sessions of behavioral counseling with practice nurse. Doctor exercise prescription was scheduled 6 wk into trial to allow groups 7 and 8 to have Alexander technique lessons before starting exercise but not to delay any further the start for group 5.

‡ Two lessons/wk for 2 wk, then one lesson/wk for 2 wk.

§ Twenty-two lessons over 5 mo, initially two lessons/wk for 6 wk, one lesson/wk for 6 wk, one lesson every 2 wk for 8 wk, and one revision lesson at 7 mo, and one at 9 mo.

From Little P, Lewith G, Webley F, et al: Randomized controlled trial of Alexander technique lessons, exercise, and massage (ATEAM) for chronic and recurrent back pain. BMJ 2008;337:a884.

At follow-up after 3 months, the patients in the massage and Alexander technique groups reported statistically significant fewer days with back pain in the previous month when compared with the control group (Table 21-11). The patients who received 24 sessions of Alexander technique had the greatest mean decrease in days with back pain with an average of 16 fewer days. The exercise prescription group also showed a modest effect, decreasing the number of days with pain in a month by 6.

Table 21-11 Outcomes at 3 Months after Randomization. Values are Mean Differences Compared with Control Group (95% Confidence Intervals) and P Values, Unless Stated Otherwise

In addition, at 1-year follow-up, the group who received 24 lessons in Alexander technique continued to have significantly fewer days with pain (a mean of 18 fewer days) (Table 21-12). The participants who had received 6 lessons on Alexander technique or massage also had significantly fewer days with pain (10 fewer and 7 fewer, respectively). At 1 year, however, the exercise group failed to show significantly fewer days with pain.

Body Awareness Therapy

Basic body awareness therapy (BAT) is a method of increasing the quality of movement through an increase in body awareness. The Basic Body Awareness Therapy uses everyday activities such as walking and standing but it can also incorporate a wide range of psychophysical practices including Yoga and Tai Chi Chuan. BAT is based on Jacques Dropsy’s movement system.121 The Feldenkrais method is a specific form of BAT that focuses on allowing people to move in more efficient ways.

The Feldenkrais method was developed by Moshe Feldenkrais in response to a personal knee injury. Using his knowledge of athletics, Feldenkrais explored different forms of movement with his knee, learning to use the least painful method.122 Eventually, he learned to walk again without pain. Publishing his understanding of the process in Body and Mature Behavior and then again in a more refined manner in Awareness Through Motion, Feldenkrais eventually began to teach his method in classes in 1969. By the time of his death in 1984, Feldenkrais trained about 300 practitioners his method.

The emphasis of the Feldenkrais method is to help afflicted individuals reduce their pain through an understanding of more efficient movement. The method applies not only to chronic physical conditions but also to mental conditions. In Body and Mature Behavior, Feldenkrais finds “successful action” as action that requires the least amount of exertion.123 An example of an exercise of the method includes shifting weight between the left and right side of the body, then becoming more complex with vertical and horizontal movement. Simplicity and working at one’s own comfort level are fundamental throughout the process. One practitioner stated: “Because there were contrasting sensations in each side, my physical awareness increased…So automatic is goal-oriented work that one doesn’t recognize effort, as such, until led to a heightened state of awareness where subtle energy differences can be perceived.”

Several studies in Scandinavia have demonstrated the advantage of BAT over traditional physiotherapeutic treatment, especially when it is part of a multidisciplinary approach. One prospective, controlled, follow-up study by Grahn and colleagues at Lund University in Sweden124 investigated patients with prolonged musculoskeletal disorders (i.e., more than 6 months). The 122 patients in the rehabilitation group received BAT and cognitive and relaxation therapy for 4 weeks. Matched controls (114 patients) received traditional treatment within primary care, medical examination, advice, prescription of medicine, assessment of the need for sick leave, and a referral for physiotherapy. The rehabilitation group’s pain rating on the VAS improved from a mean of 67.5 to 59.4 after 6-month follow-up (P = .0005). Conversely, the control group did not show a significant improvement in pain rating at follow-up.

A 2002 study by Gustafsson and colleagues,125 also in Sweden, studied 43 women with fibromyalgia or chronic, widespread pain who were nonrandomly assigned to receive either a multidisciplinary rehabilitation program including BAT or no therapy program. The experimental group did not demonstrate improvement of pain with BAT that was superior to the control group, although there were other benefits such as movement quality.

BAT and Feldenkrais alone (not as part of a multimodal approach) have been compared to other physical therapies. In another Swedish study,126 78 patients with nonspecific musculoskeletal disorders were recruited consecutively over a period of 9 months. Physical complaints included headache, neck and shoulder pain, and back pain. Patients received 20 sessions of either Basic BAT, Feldenkrais or conventional physiotherapy (based on which health care district they presented to) over 4 to 5 months. Pain was assessed before treatment, at 6 months, and at 1 year by the 36-item Short Form Health Survey.127 All three groups had a significant decrease in bodily pain over time, but effect-size analysis indicated that Basic BAT and Feldenkrais may be more effective than conventional treatment. Basic BAT and Feldenkrais both had a large effect size (greater than 1.0), whereas conventional therapy had a small effect size (less than 0.5).

Two different types of BAT, Basic BAT and Mensendieck, have been directly compared. This pilot study examined 20 female patients with fibromyalgia who were randomized to receive one of the two therapies for 20 weeks. At 18 months follow-up, the patients who received Mensendieck therapy improved more in terms of symptom reduction and pain relief than those who received Basic BAT. For example, on the Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale, one of the questionnaires administered to all participants, those who received Mensendieck rated their pain control 62/100 six months after therapy. Those who received basic BAT rated their pain control only 32/100 at this same point in time.128

Several cases of patients with chronic lower back pain who responded to the Feldenkrais method after failing a variety of traditional and nontraditional methods were reported by an Australian family physician.129 He photographically documented their changes in posture following treatment. However, he demonstrates only improved posture in his report, not an objective or subjective decrease in pain. One cannot assume that improved posture and body positioning necessarily relieves lower back pain.

A 1977 Canadian study recruited participants from two retirement housing complexes in British Columbia. They received detailed health evaluations including measurement of height, weight, blood pressure, heart rate, flexibility, and number of body parts difficult to move or giving rise to pain. They were then assigned to receive a conventional exercise program, Feldenkrais exercises, or no exercise program over 6 weeks. Subsequent measurements failed to demonstrate any significant differences between groups. This study was confounded by the fact that nearly 50% of the subjects dropped out or were unable to complete at least half the sessions.130

Given the equivocal data and dearth of research, a 2004 article by Maher131 evaluating various treatments for chronic lower back pain labeled Feldenkrais as being of “unknown efficacy.” According to the author, there is insufficient evidence for it to be considered by doctors or therapists for treating pain. A summary table from this article on the efficacy of physical treatments for chronic lower back pain is in Table 21-8. Overall, it seems that BAT, including Feldenkrais, can potentially improve pain and no studies so far indicate that it has negative effects. However, BAT needs to be further studied with larger, controlled trials before it is seriously considered an option by doctors for pain management.

[M2]How was pain measured? By how much (%) did it improve?

[M4]Data? By what % did pain decrease?

1. Snyder M., Lindquist R. Complementary/Alternative Therapies in Nursing, 5th ed. New York: Springer. 2006. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/nyulibrary/Doc?id=10171392&ppg=118. 108

2. Wainapel S.F., Fast A., editors. Alternative medicine and rehabilitation: A guide for practitioners. New York: Demos Medical. 2002:139. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/nyulibrary/Doc?id=10118505&ppg=151.

3. Fishman http://site.ebrary.com/lib/nyulibrary/Doc?id=10118505&ppg=152.

4. Cameron http://site.ebrary.com/lib/nyulibrary/Doc?id=10171392&ppg=119.

5. Fishman http://site.ebrary.com/lib/nyulibrary/Doc?id=10118505&ppg=153.

6. Wilson R.L. An introduction to yoga. AJN. 1976;76(2):261-263.

7. Wilson R.L. An introduction to yoga. AJN. 1976;76(2):263.

8. Groessl E.J., Weingart K.R., Aschbacher K., et al. Yoga for veterans with chronic low-back pain. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(9):1123-1129.

9. Tekur P., Singphow C., Nagendra H.R., Raghuram N. Effect of short-term intensive yoga program on pain, functional disability and spinal flexibility in chronic low back pain: A Randomized control study. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(6):637-644.

10. Kolasinski S.L., Garfinkel M., Tsai A.G., et al. Iyengar yoga for treating symptoms of osteoarthritis of the knees: A pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:689-693.

11. Williams K.A., Petronis J., Smith D., et al. Effect of Iyengar yoga therapy for chronic low back pain. Pain. 2005;115:107-117.

12. Melzack R. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain. 1987;30:191-197.

13. Huskisson E.C. Visual analogue scales. In: Melzack R., editor. Pain Measurement and Assessment. New York: Raven Press; 1983:33-37.

14. Sherman K.J., Cherkin D.C., Erro J., et al. Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:849-856.

15. Da Silva G.D., Lorenzi-Filho G., Lage L.V. Effects of yoga and the addition of Tui Na in patients with fibromyalgia. J Altern Complement Med. 13(10), 2007. 1107–1013

16. Morone N.E., Greco C.M. Mind-body interventions for chronic pain in older adults: A structured review. Pain Med. 2007;8:359-375.

17. John P.J., Sharma N., Sharma C.M., et al. Effectiveness of yoga therapy in the treatment of migraine without aura: A randomized controlled trial. Headache. 2007;47:654-661.

18. Garfinkel M.S., Singhal A., Katz W.A., et al. Yoga-based intervention for carpal tunnel syndrome: A randomized trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1601-1603.

19. Michlovitz S.L. Conservative interventions for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34:589-600.

20. Garfinkel M.S., Schumacher H.R.Jr., Husain A., et al. Evaluation of a yoga based regimen for treatment of osteoarthritis of the hands. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2341-2343.

21. Carson J.W., Carson K.M., Porter L.S., et al. Yoga for women with metastatic breast cancer: Results from a pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:331-341.

22. Chou R., Qaseem A., Snow V., et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: A joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:478-491.

23. “What Is Pilates?” http://www.pilates.com/BBAPP/V/pilates/index.html

24. “Pilates Origins.” http://www.pilates.com/BBAPP/V/pilates/origins-of-pilates.html

25. “Getting Started.”http://www.pilates.com/BBAPP/V/pilates/getting-started.html

26. Maher C.G. Effective physical treatment for chronic low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am. 2004;35(1):57-64.

27. La Touche R., Escalante K., Linares M.T. Treating non-specific chronic low back pain through the Pilates method. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2008;12:364-370.

28. Verhagen A.P., de Vet H.C., de Bie R.A., et al. The Delphi list: A criteria list for quality assessment of randomized clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by Delphi consensus. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(12):1235-1241.

29. Jadad A.R., Moore R.A., Carroll D., et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1-12.

30. Donzelli S., Di Domenica E., Cova A.M., et al. Two different techniques in the rehabilitation treatment of low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Eura Medicophys. 2006;42:205-210.

31. Rydeard R., Leger A., Smith D. Pilates-based therapeutic exercise: Effect on subjects with nonspecific chronic low back pain and functional disability: A randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:472-484.

32. Keays K.S., Harris S.R., Lucyshyn J.M., et al. Effects of Pilates exercises on shoulder range of motion, pain, mood, and upper-extremity function in women living with breast cancer: A pilot study. Phys Ther. 2008;88:494-510.

33. Cleeland C.S., Ryan K.M. Pain assessment: Global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23:129-138.

34. Tan J.C., Wainapel S.F. Alternative Medicine and Rehabilitation. A Guide for Practitioners. New York: Demos Medical. 2002:77. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/nyulibrary/Doc?id=10118505&ppg=89.

35. Tan JC. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/nyulibrary/Doc?id=10118505&ppg=90.

36. Snyder M. Complementary/alternative therapies in nursing, 5th ed. New York: Springer. 2006. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/nyulibrary/Doc?id=10171392&ppg=291. 288

37. Sherman K.J., Cherkin D.C., Deyo R.A., et al. The diagnosis and treatment of chronic back pain by acupuncturists, chiropractors, and massage therapists. Clin J Pain. 2006;22(3):227-234.

38. Wells M., Sarna L., Cooley M.E., et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine therapies to control symptoms in women living with lung cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30(1):45-55.

39. Wolsko P.M., Eisenberg D.M., Davis R.B., et al. Patterns and perceptions of care for treatment of back and neck pain: Results of a national survey. Spine. 2003;28(3):292-297.

40. Brett K.M., Keenan N.L. Complementary and alternative medicine use among midlife women for reasons including menopause in the United States: 2002. Menopause. 2007;14(2):300-307.

41. Palinkas L.A., Kabongo M.L., San Diego Unified Practice Research in Family Medicine Network. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by primary care patients. A SURF∗NET study. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(12):1121-1130.

42. Williamson A.T., Fletcher P.C., Dawson K.A. Complementary and alternative medicine. Use in an older population. J Gerontol Nurs. 2003;29(5):20-28.

43. Drivdahl C.E., Miser W.F. The use of alternative health care by a family practice population. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11(3):193-199.

44. Feinglass J., Lee C., Rogers M., et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use for arthritis pain in 2 Chicago community areas. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(9):744-749.

45. McCasland L.D., Budiman-Mak E., Weaver F.M., et al. Shoulder pain in the traumatically injured spinal cord patient: Evaluation of risk factors and function. JCR: J Clin Rheumatol. 2006;12(4):179-186.

46. Ernst E. Manual therapies for pain control: Chiropractic and massage. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(1):8-12.

47. Moyer C.A., Rounds J., Hannum J.W. A meta-analysis of massage therapy research. Psychol Bul. 2004;130(1):3-18.

48. Back C., Tam H., Lee E., Haraldsson B. The effects of employer-provided massage therapy on job satisfaction, workplace stress, and pain and discomfort. Holist Nurs Pract. 2009;23(1):19-31.

49. Cleeland C.S., Ryan K.M. Pain assessment: Global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(2):129-138.

50. Trinh K., Graham N., Gross A., et al. Acupuncture for neck disorders. Spine. 2007;32(2):236-243.

51. Ezzo J., Haraldsson B.G., Gross A.R., et al. Massage for mechanical neck disorders: A systematic review. Spine. 2007;32(3):353-362.

52. Cherkin D.C., Sherman K.J., Deyo R.A., et al. A review of the evidence for the effectiveness, safety, and cost of acupuncture, massage therapy, and spinal manipulation for back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(11):898-906.

53. Furlan A.D., Brosseau L., Imamura M., et al. Massage for low-back pain: A systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine. 2002;27(17):1896-1910.

54. Wright A., Sluka K.A. Nonpharmacological treatments for musculoskeletal pain. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(1):33-46.

55. Best T.M., Hunter R., Wilcox A., Haq F. Effectiveness of sports massage for recovery of skeletal muscle from strenuous exercise. Clin J Sport Med. 2008;18(5):446-460.

56. Moraska A. Therapist education impacts the massage effect on postrace muscle recovery. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(1):34-37.

57. Dryden T., Baskwill A., Preyde M. Massage therapy for the orthopaedic patient: A review. Orthop Nurs. 2004;23(5):327-332.

58. Bennell K.L., Hinman R.S., Metcalf B.R., et al. Efficacy of physiotherapy management of knee joint osteoarthritis: A randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(6):906-912.

59. Ferrell-Torry A.T., Glick O.J. The use of therapeutic massage as a nursing intervention to modify anxiety and the perception of cancer pain. Cancer Nurs. 1993;16(2):93-101.

60. Grealish L., Lomasney A., Whiteman B. Foot massage. A nursing intervention to modify the distressing symptoms of pain and nausea in patients hospitalized with cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2000;23(3):237-243.

61. Currin J., Meister E.A. A hospital-based intervention using massage to reduce distress among oncology patients. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(3):214-221.

62. Jane S.W., Wilkie D.J., Gallucci B.D., Beaton R.D. Systematic review of massage intervention for adult patients with cancer: A methodological perspective. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(6):E24-E35.

63. Williams P.D., Schmideskamp J., Ridder E.L., Williams A.R. Symptom monitoring and dependent care during cancer treatment in children: Pilot study. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(3):188-197.

64. Simkin P.P., O’hara M. Nonpharmacologic relief of pain during labor: Systematic reviews of five methods. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5 Suppl Nature):S131-S159.

65. Chang M.Y., Chen C.H., Huang K.F. A comparison of massage effects on labor pain using the McGill Pain Questionnaire. J Nurs Res. 2006;14(3):190-197.

66. Tzeng Y.L., Su T.J. Low back pain during labor and related factors. J Nurs Res. 2008;16(3):231-241.

67. Stamp G., Kruzins G., Crowther C. Perineal massage in labour and prevention of perineal trauma: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322(7297):1277-1280.

68. Bellieni C.V., Bagnoli F., Perrone S., et al. Effect of multisensory stimulation on analgesia in term neonates: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Res. 2002;51(4):460-463.

69. Bellieni C.V., Cordelli D.M., Marchi S., et al. Sensorial saturation for neonatal analgesia. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(3):219-221.

70. Forchuk C., Baruth P., Prendergast M., et al. Postoperative arm massage: A support for women with lymph node dissection. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27(1):25-33.

71. Anderson P.G., Cutshall S.M. Massage therapy: A comfort intervention for cardiac surgery patients. Clin Nurse Spec. 2007;21(3):161-165.

72. Carrieri-Kohlman V., Lindsey A., West C. Pathophysiological Phenomena in Nursing, Human Responses to Illness. St. Louis: Saunders; 2003.

73. Erdogmus C.B., Resch K.L., Sabitzer R., et al. Physiotherapy-based rehabilitation following disc herniation operation: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Spine. 2007;32(19):2041-2049.

74. Mitchinson A.R., Kim H.M., Rosenberg J.M., et al. Acute postoperative pain management using massage as an adjuvant therapy: A randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2007;142(12):1158-1167.

75. Field T., Peck M., Krugman S., et al. Burn injuries benefit from massage therapy. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1998;19(3):241-244.

76. Gallagher G., Rae C.P., Kinsella J. Treatment of pain in severe burns. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1(6):329-335.

77. Hernandez-Reif M., Field T., Largie S., et al. Childrens‘ distress during burn treatment is reduced by massage therapy. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2001;22(2):191-195.

78. Schneider J.C., Harris N.L., El Shami A., et al. A descriptive review of neuropathic-like pain after burn injury. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27(4):524-528.

79. KM, Snyder M. Complementary/Alternative Therapies in Nursing, 5th ed. New York: Springer. 2006. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/nyulibrary/Doc?id=10171392&ppg=316. 313

80. Wolf S.L., O’Grady M.J., Xu T., et al, editors. Alternative Medicine and Rehabilitation: A Guide for Practitioners. New York: Demos Medical. 2002. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/nyulibrary/Doc?id=10118505&ppg=111.

81. Morton W.S., Lewis C.M. China: Its History and Culture. Blacklick, OH: McGraw-Hill. 2004. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/nyulibrary/Doc?id=10083588&ppg=66. 38

82. Morton p 39. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/nyulibrary/Doc?id=10083588&ppg=67.

83. Wolf 100. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/nyulibrary/Doc?id=10118505&ppg=112.

84. Wolf 102. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/nyulibrary/Doc?id=10118505&ppg=114.

85. Wolf 103. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/nyulibrary/Doc?id=10118505&ppg=115.

86. Klein P.J., Adams W.D. Comprehensive therapeutic benefits of Taiji: A critical review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;83(9):735-745.

87. Wahbeh H., Elsas S.M., Oken B.S. Mind-body interventions: Applications in neurology. Neurology. 2008;70(24):2321-2328.

88. Chen K.M., Snyder M. A research-based use of Tai Chi/movement therapy as a nursing intervention. J Holist Nurs. 1999;17(3):267-279.

89. Siu A.M., Chan C.C., Poon P.K., et al. Evaluation of the chronic disease self-management program in a Chinese population. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65(1):42-50.

90. Lee M.S., Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Tai chi for osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27(2):211-218.

91. Shen C.L., James C.R., Chyu M.C., et al. Effects of Tai Chi on gait kinematics, physical function, and pain in elderly with knee osteoarthritis—a pilot study. Am J Chin Med. 2008;36(2):219-232.

92. Lee H.Y., Lee K.J. Effects of Tai Chi exercise in elderly with knee osteoarthritis [Article in Korean]. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2008;38(1):11-18.

93. Wang C., Schmid C.H., Hibberd P.L., et al. Tai Chi for treating knee osteoarthritis: Designing a long-term follow up randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskel Dis. 2008;9:108.

94. Lee H.Y. Comparison of effects among Tai-Chi exercise, aquatic exercise, and a self-help program for patients with knee osteoarthritis [Article in Korean]. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2006;36(3):571-580.

95. Fransen M., Nairn L., Winstanley J., et al. Physical activity for osteoarthritis management: A randomized controlled clinical trial evaluating hydrotherapy or Tai Chi classes. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(3):407-414.

96. Song R., Lee E.O., Lam P., et al. Effects of a Sun-style Tai Chi exercise on arthritic symptoms, motivation and the performance of health behaviors in women with osteoarthritis. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2007;37(2):249-256.

97. Brismee J.M., Paige R.L., Chyu M.C., et al. Group and home-based tai chi in elderly subjects with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(2):99-111.

98. Han A., Robinson V., Judd M., et al. Tai chi for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2004. CD004849

99. Yocum D.E., Castro W.L., Cornett M. Exercise, education, and behavioral modification as alternative therapy for pain and stress in rheumatic disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2000;26(1):145-159. x–xi

100. Lee M.S., Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Tai chi for rheumatoid arthritis: Systematic review. Rheumatology. 2007;46(11):1648-1651.

101. Lee K.Y., Jeong O.Y. The effect of Tai Chi movement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [Article in Korean]. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2006;36(2):278-285.

102. Koh T.C. Tai Chi and ankylosing spondylitis—a personal experience. Am J Chin Med. 1982;10(1-4):59-61.

103. Wang Y.T., Taylor L., Pearl M., Chang L.S. Effects of Tai Chi exercise on physical and mental health of college students. Am J Chin Med. 2004;32(3):453-459.

104. Wang Y. Tai Chi exercise and the improvement of mental and physical health among college students. Med Sport Sci. 2008;52:135-145.

105. Reid M.C., Papaleontiou M., Ong A., et al. Self-management strategies to reduce pain and improve function among older adults in community settings: A review of the evidence. Pain Med. 2008;9(4):409-424.

106. Morone N.E., Greco C.M. Mind-body interventions for chronic pain in older adults: A structured review. Pain Med. 2007;8(4):359-375.

107. Ross M.C., Bohannon A.S., Davis D.C., Gurchiek L. The effects of a short-term exercise program on movement, pain, and mood in the elderly. Results of a pilot study. J Holist Nurs. 1999;17(2):139-147.

108. Ho T.J., Liang W.M., Lien C.H., et al. Health-related quality of life in the elderly practicing T’ai Chi Chuan. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(10):1077-1083.

109. Kin S., Toba K., Orimo H. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in older people practicing Tai Chi—comparison of the HRQOL with the national standards for age-matched controls [Article in Japanese]. Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 2007 May;44(3):339-344.