Chapter 1 Basic Principles and Pharmacodynamics

Drug Nomenclature

Trade, Brand, or Proprietary Name

Clinical Connection: Drugs can have many different names. For example, a prototypical calcium channel blocker of the dihydropyridine class has the chemical name 3,5-dimethyl 2,6-dimethyl-4-(2-nitrophenyl)-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate, the generic name nifedipine, and is available in the United States under several trade names including Adalat, Nifedical, and Procardia. Although marketing emphasizes trade names, the use of generic drug names is encouraged in practice to reduce prescribing errors and offers the opportunity for substitutions if appropriate.

Clinical Connection: Drugs can have many different names. For example, a prototypical calcium channel blocker of the dihydropyridine class has the chemical name 3,5-dimethyl 2,6-dimethyl-4-(2-nitrophenyl)-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate, the generic name nifedipine, and is available in the United States under several trade names including Adalat, Nifedical, and Procardia. Although marketing emphasizes trade names, the use of generic drug names is encouraged in practice to reduce prescribing errors and offers the opportunity for substitutions if appropriate.Drug-Receptor Interactions

Although some notable exceptions exist, a fundamental principle of pharmacology is that drugs must interact with a molecular target to exert an effect. Drug interaction with molecular targets is the initiating event in a multistep process that ultimately alters tissue function. For the purposes of current discussion, the target will be referred to as a receptor. An in-depth discussion of molecular targets and a description of these processes will be presented later in this chapter (see the discussion of molecular mechanisms of drug action). Let us first consider the relationship between drug binding to its target receptors and the ultimate response of the tissue.

A minimum number of drug receptor complexes must be formed for a response to be initiated (threshold)

A minimum number of drug receptor complexes must be formed for a response to be initiated (threshold) As drug concentration increases, the number of drug-receptor complexes increases and drug effect increases

As drug concentration increases, the number of drug-receptor complexes increases and drug effect increases A point will be reached at which all receptors are bound to drug, and therefore no further drug-receptor complexes can be formed and the response does not increase any further (saturation)

A point will be reached at which all receptors are bound to drug, and therefore no further drug-receptor complexes can be formed and the response does not increase any further (saturation)Law of Mass Action Applied to Drugs

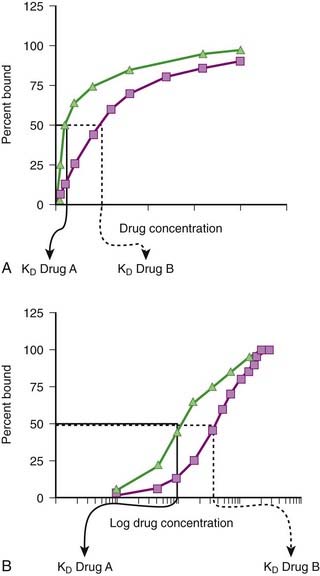

Although the amount of drug receptor-complex formed is proportional to the concentrations of drug and receptor, this relationship is not linear but is in fact parabolic (Figure 1-1, A). Accordingly, this relationship is most often diagrammed on a semilogarithmic graph to linearize the relationship and encompass the large range of concentrations typical of the drug-receptor relationship (Figure 1-1, B).

Factors Affecting Drug-Target Interactions

Drug Binding

It is important to recognize that, in most cases, binding of drug to target molecules involves weaker bonds. Accordingly, the drug-receptor complex is not static, but rather there is continuous association and dissociation of the drug with the receptor as long as drug is present. A measure of the relative ease with which the association and dissociation reactions occur is the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD). Each drug-receptor combination will have a characteristic KD value. Drugs with high affinity for a given receptor display a small value for KD, and vice versa. In Figure 1-1, A and B, Drug A has a higher affinity for the receptor than Drug B. KD also represents the concentration of drug needed to bind 50% of the total receptor population. These concepts are important in the study of basic pharmacologic data regarding different compounds with affinity for the same receptor. In general, drugs with lower KD values will require lower concentrations to achieve sufficient receptor occupancy to exert an effect.

Selectivity of Drug Responses

The cell will respond only to the spectrum of drugs that exhibit affinity for the receptors expressed by the cell.

The cell will respond only to the spectrum of drugs that exhibit affinity for the receptors expressed by the cell. The greater the extent to which a drug molecule exhibits high affinity for only one receptor, the more selective will be the drug’s actions, with lower potential for side effects.

The greater the extent to which a drug molecule exhibits high affinity for only one receptor, the more selective will be the drug’s actions, with lower potential for side effects. The higher the affinity and efficacy of a given drug, the smaller the amount of drug necessary to activate a critical mass of drug receptors to effect a tissue response, and the lower the potential for nonselective actions.

The higher the affinity and efficacy of a given drug, the smaller the amount of drug necessary to activate a critical mass of drug receptors to effect a tissue response, and the lower the potential for nonselective actions. Clinical Connection: β-Adrenergic receptor antagonists are effective drugs for a number of cardiovascular disorders. Some β-adrenergic receptor antagonists are selective for β1-adrenergic receptors to limit the potential for bronchoconstriction caused by blocking β2-adrenergic receptors. However, even β1-selective antagonists must be used cautiously in asthmatic patients, particularly at higher doses, to avoid further impairment of airway function in these patients.

Clinical Connection: β-Adrenergic receptor antagonists are effective drugs for a number of cardiovascular disorders. Some β-adrenergic receptor antagonists are selective for β1-adrenergic receptors to limit the potential for bronchoconstriction caused by blocking β2-adrenergic receptors. However, even β1-selective antagonists must be used cautiously in asthmatic patients, particularly at higher doses, to avoid further impairment of airway function in these patients.Tissue Distribution of Receptors

The more restricted the distribution of drug receptor, the more selective will be the effects of drugs that interact with that receptor.

The more restricted the distribution of drug receptor, the more selective will be the effects of drugs that interact with that receptor. Clinical Connection: Knowledge of receptor subtypes and their regional distribution can assist in drug selection. A useful example is the use of α-adrenergic receptor antagonists for the treatment of urinary retention secondary to prostatic hypertrophy. Nonselective α-adrenergic antagonists are not routinely used to treat urinary retention in men with prostatic hypertrophy, because although they block α receptors in the prostate and improve urine flow, they also block α receptors in blood vessels and cause hypotension. The prostate expresses primarily α1B-adrenergic receptors, whereas blood vessels express other subtypes. Consequently, drugs such as tamsulosin that are selective for the α1B subtype expressed primarily in the prostate are much more useful in the treatment of prostatic hypertrophy.

Clinical Connection: Knowledge of receptor subtypes and their regional distribution can assist in drug selection. A useful example is the use of α-adrenergic receptor antagonists for the treatment of urinary retention secondary to prostatic hypertrophy. Nonselective α-adrenergic antagonists are not routinely used to treat urinary retention in men with prostatic hypertrophy, because although they block α receptors in the prostate and improve urine flow, they also block α receptors in blood vessels and cause hypotension. The prostate expresses primarily α1B-adrenergic receptors, whereas blood vessels express other subtypes. Consequently, drugs such as tamsulosin that are selective for the α1B subtype expressed primarily in the prostate are much more useful in the treatment of prostatic hypertrophy.Activation of the Molecular Target

Agonists (sometimes called full agonists) produce maximum activation of the receptor and elicit a maximum response from the tissue. They are assigned an intrinsic activity of 1.

Agonists (sometimes called full agonists) produce maximum activation of the receptor and elicit a maximum response from the tissue. They are assigned an intrinsic activity of 1. Antagonists bind but produce no activation of the receptor and therefore block responses from the tissue. They are assigned an intrinsic activity of 0.

Antagonists bind but produce no activation of the receptor and therefore block responses from the tissue. They are assigned an intrinsic activity of 0. Partial agonists exhibit intrinsic activity between 0 and 1. Partial agonists produce weaker activation of the receptor than full agonists or the endogenous ligand. Partial agonists produce only partial activation of the receptor and its downstream signaling events. The clinical effect of a partial agonist will depend on its intrinsic activity and the concentration of the endogenous ligand. If concentrations of the endogenous ligand are really low, then a partial agonist will increase receptor activation, functioning as a weak agonist. In contrast, if concentrations of endogenous ligand are high, the partial agonist will compete for receptors and bind to a certain proportion of receptors previously bound by endogenous ligand. Because the partial agonist produces weaker activation of the receptor than endogenous ligand, the net effect will be less cumulative receptor activation. This will produce inhibition of the response mediated by the endogenous ligand, and the partial agonist will act as a weak antagonist.

Partial agonists exhibit intrinsic activity between 0 and 1. Partial agonists produce weaker activation of the receptor than full agonists or the endogenous ligand. Partial agonists produce only partial activation of the receptor and its downstream signaling events. The clinical effect of a partial agonist will depend on its intrinsic activity and the concentration of the endogenous ligand. If concentrations of the endogenous ligand are really low, then a partial agonist will increase receptor activation, functioning as a weak agonist. In contrast, if concentrations of endogenous ligand are high, the partial agonist will compete for receptors and bind to a certain proportion of receptors previously bound by endogenous ligand. Because the partial agonist produces weaker activation of the receptor than endogenous ligand, the net effect will be less cumulative receptor activation. This will produce inhibition of the response mediated by the endogenous ligand, and the partial agonist will act as a weak antagonist. Inverse agonists inhibit rather than activate the receptor. This phenomenon is evident with receptors that exhibit baseline (ongoing or constitutive) activity in the absence of agonist binding. In these cases, binding of the inverse agonist reduces the baseline activity of the receptor, which in turn elicits an effect opposite that of binding of the agonist. Inverse agonists and antagonists will elicit similar effects because both types of drugs will reverse the effects of endogenous ligands. Many clinically used antagonists may in fact be inverse agonists. Inverse agonists may assume particular clinical importance in disease states in which constitutive activity of receptors plays an important role. Increasing evidence suggests that a number of diseases are a result of gain of function mutations at the receptor that result in constitutive activity of the receptor in the absence of agonist.

Inverse agonists inhibit rather than activate the receptor. This phenomenon is evident with receptors that exhibit baseline (ongoing or constitutive) activity in the absence of agonist binding. In these cases, binding of the inverse agonist reduces the baseline activity of the receptor, which in turn elicits an effect opposite that of binding of the agonist. Inverse agonists and antagonists will elicit similar effects because both types of drugs will reverse the effects of endogenous ligands. Many clinically used antagonists may in fact be inverse agonists. Inverse agonists may assume particular clinical importance in disease states in which constitutive activity of receptors plays an important role. Increasing evidence suggests that a number of diseases are a result of gain of function mutations at the receptor that result in constitutive activity of the receptor in the absence of agonist. Clinical Connection: Drugs that act as inverse agonists may have important clinical applications for diseases in which receptors are activated in the absence of endogenous agonist. One example is in cancer chemotherapy. In a number of human cancers, mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor cause the receptor to be active in the absence of epidermal growth factor. In this setting, a traditional antagonist would be of no benefit. However, drugs that act as inverse agonists at the epidermal growth factor would suppress receptor activation and reduce the growth signaling via this pathway. Epidermal growth factor inverse agonists are being studied as cancer chemotherapy drugs.

Clinical Connection: Drugs that act as inverse agonists may have important clinical applications for diseases in which receptors are activated in the absence of endogenous agonist. One example is in cancer chemotherapy. In a number of human cancers, mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor cause the receptor to be active in the absence of epidermal growth factor. In this setting, a traditional antagonist would be of no benefit. However, drugs that act as inverse agonists at the epidermal growth factor would suppress receptor activation and reduce the growth signaling via this pathway. Epidermal growth factor inverse agonists are being studied as cancer chemotherapy drugs.Quantifying Drug-Target Interactions: Dose-Response Relationships

Graded Dose-Response Curves

Measure an effect that is continuous such that, in theory, any value is possible in a given range (0% through 100%).

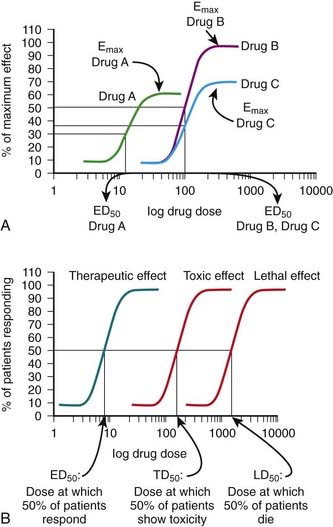

Measure an effect that is continuous such that, in theory, any value is possible in a given range (0% through 100%). Have a sigmoidal shape similar to the drug receptor occupancy curves shown in Figure 1-2, because the biologic response to a drug is determined by the interaction of a drug with a receptor or molecular target.

Have a sigmoidal shape similar to the drug receptor occupancy curves shown in Figure 1-2, because the biologic response to a drug is determined by the interaction of a drug with a receptor or molecular target. Exhibit a dose beyond which no further response is achieved (maximal effect; Emax). Emax is a measure of the pharmacologic efficacy of the drug.

Exhibit a dose beyond which no further response is achieved (maximal effect; Emax). Emax is a measure of the pharmacologic efficacy of the drug.The ED50 and Emax are useful parameters to assess drugs. In Figure 1-2, A, Drug A is more potent than Drug B or Drug C, whereas Drugs B and C have equal potency. Potency is sometimes used incorrectly as a measure of therapeutic effectiveness. In fact, in most cases potency is secondary to Emax in drug selection. However, in situations in which the absorption of drug is very poor, such that only small quantities of the drug reach the target, potency can be a critical consideration. Drugs with higher Emax values have higher pharmacologic efficacy.

In Figure 1-2, A, Drug B has the greatest efficacy, followed by Drug C, whereas Drug A, despite being the most potent, has the least efficacy. Drug C is equipotent with Drug B but has less efficacy. Thus, potency and efficacy can vary independently. It is important not to confuse the pharmacologic usage of efficacy with the more general usage. Pharmacologic efficacy is a measure of the strength of effect produced by the maximum dose of drug. By definition, antagonists do not activate their receptors after binding and therefore have an intrinsic activity and efficacy of 0. Nevertheless, an antagonist may be very clinically “efficacious” or beneficial because it blocks activation of the receptor by endogenous agonist.

Quantal Dose-Response Curves

Quantal dose-response curves do the following:

Describe the relationship between drug dosage and the frequency with which a biologic effect occurs. For example, in individuals administered an anticonvulsant medication, the percentage of individuals not experiencing a convulsive episode at any given dose is plotted in cumulative fashion (Figure 1-2, B).

Describe the relationship between drug dosage and the frequency with which a biologic effect occurs. For example, in individuals administered an anticonvulsant medication, the percentage of individuals not experiencing a convulsive episode at any given dose is plotted in cumulative fashion (Figure 1-2, B). Represent a cumulative frequency distribution for a given response.

Represent a cumulative frequency distribution for a given response.

Provide an ED50 value that reflects the dose of drug that produces a response in 50% of the population (also called the median effective dose).

Provide an ED50 value that reflects the dose of drug that produces a response in 50% of the population (also called the median effective dose). Provide an estimate of the variability in response of the patient population to the drug. A steep slope indicates that all the patients respond in a narrow range of doses, whereas a shallow slope indicates considerable variability in the ability of the drug to elicit a response in the patient population.

Provide an estimate of the variability in response of the patient population to the drug. A steep slope indicates that all the patients respond in a narrow range of doses, whereas a shallow slope indicates considerable variability in the ability of the drug to elicit a response in the patient population. Can be constructed for a graded or continuous response by choosing a target magnitude of response (e.g., blood pressure reduction of 20 mm Hg) and plotting the proportion of patients that achieves this magnitude of response at each increase in dosage. This type of information can be useful in determining a starting dosage to achieve a given level of effect

Can be constructed for a graded or continuous response by choosing a target magnitude of response (e.g., blood pressure reduction of 20 mm Hg) and plotting the proportion of patients that achieves this magnitude of response at each increase in dosage. This type of information can be useful in determining a starting dosage to achieve a given level of effect Can be plotted for therapeutic, toxic, and lethal effects to obtain:

Can be plotted for therapeutic, toxic, and lethal effects to obtain:

Antagonism as a Mechanism of Drug Action

Physiologic (Functional) Antagonists

Physiologic antagonists represent another type of antagonism in which the antagonist does not interact directly with the actions of the agonist at its molecular target.

Physiologic antagonists represent another type of antagonism in which the antagonist does not interact directly with the actions of the agonist at its molecular target. The agonist and antagonist each act on different molecular targets, but the responses elicited by these interactions are diametrically opposed and negate each other.

The agonist and antagonist each act on different molecular targets, but the responses elicited by these interactions are diametrically opposed and negate each other. Epinephrine and histamine are good examples of physiologic antagonists. Histamine is a vasodilator and bronchoconstrictor. Histamine release in anaphylactic reactions can cause hypotension and respiratory compromise. Epinephrine supports blood pressure and causes bronchodilation but does not act through the histamine receptor. Thus, epinephrine is given as acute treatment for anaphylactic reactions in part because it is a physiologic antagonist to histamine.

Epinephrine and histamine are good examples of physiologic antagonists. Histamine is a vasodilator and bronchoconstrictor. Histamine release in anaphylactic reactions can cause hypotension and respiratory compromise. Epinephrine supports blood pressure and causes bronchodilation but does not act through the histamine receptor. Thus, epinephrine is given as acute treatment for anaphylactic reactions in part because it is a physiologic antagonist to histamine.Pharmacokinetic Antagonists

Pharmacologic Antagonists

Competitive reversible antagonism (also called competitive surmountable antagonism)

Competitive reversible antagonism (also called competitive surmountable antagonism)

The antagonist competes directly for the target receptor with the agonist molecule. These interactions will follow the law of mass action and the same general principles described earlier, with the added facet that now two drugs are competing for receptor occupancy.

The antagonist competes directly for the target receptor with the agonist molecule. These interactions will follow the law of mass action and the same general principles described earlier, with the added facet that now two drugs are competing for receptor occupancy. Because there is a fixed number of receptors (at least in the short term), each antagonist-receptor complex formed removes receptor molecules from the mass action equation and reduces the likelihood of formation of an agonist-receptor complex.

Because there is a fixed number of receptors (at least in the short term), each antagonist-receptor complex formed removes receptor molecules from the mass action equation and reduces the likelihood of formation of an agonist-receptor complex. Owing to the constant competition for receptors, the concentrations and affinities for both the agonist and antagonist drugs will determine the overall balance of the mass action equation.

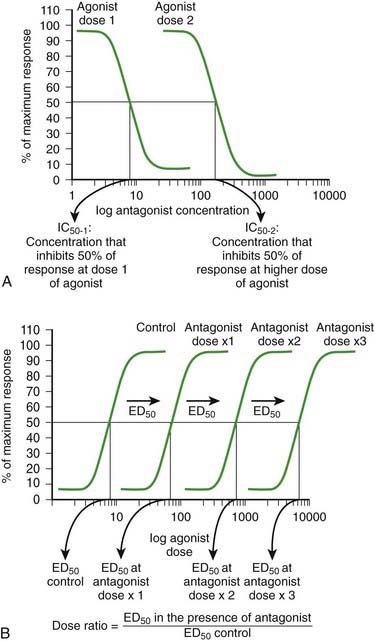

Owing to the constant competition for receptors, the concentrations and affinities for both the agonist and antagonist drugs will determine the overall balance of the mass action equation. As the concentration of antagonist increases, the number of antagonist-receptor complexes increases and the number of agonist-receptor complexes decreases. Therefore the agonist effect decreases. Figure 1-3, A shows a graded dose-response curve for increasing concentrations of antagonist in the presence of a fixed concentration of agonist. The concentration of antagonist that reduces the agonist response to 50% of maximum is the IC50, one index for quantifying antagonist effectiveness. Note that IC50 values vary with agonist starting concentration.

As the concentration of antagonist increases, the number of antagonist-receptor complexes increases and the number of agonist-receptor complexes decreases. Therefore the agonist effect decreases. Figure 1-3, A shows a graded dose-response curve for increasing concentrations of antagonist in the presence of a fixed concentration of agonist. The concentration of antagonist that reduces the agonist response to 50% of maximum is the IC50, one index for quantifying antagonist effectiveness. Note that IC50 values vary with agonist starting concentration. The greater the affinity of the antagonist, the greater the number of antagonist-receptor complexes formed at any given concentration of antagonist.

The greater the affinity of the antagonist, the greater the number of antagonist-receptor complexes formed at any given concentration of antagonist. The agonist-antagonist relationship can also be depicted on agonist dose-response curves. Figure 1-3, B illustrates graded agonist dose-response curves in the absence (control) and presence of increasing doses of antagonist.

The agonist-antagonist relationship can also be depicted on agonist dose-response curves. Figure 1-3, B illustrates graded agonist dose-response curves in the absence (control) and presence of increasing doses of antagonist. Addition of antagonist causes a reduction of agonist-driven response at any concentration of the agonist. It is important to note, however, that as the agonist concentration is increased, response increases because of greater competition for the receptors by the agonist. Ultimately, an agonist concentration will be reached, at which all of the receptors needed to elicit a maximal response are occupied by agonist and a maximal effect will be elicited.

Addition of antagonist causes a reduction of agonist-driven response at any concentration of the agonist. It is important to note, however, that as the agonist concentration is increased, response increases because of greater competition for the receptors by the agonist. Ultimately, an agonist concentration will be reached, at which all of the receptors needed to elicit a maximal response are occupied by agonist and a maximal effect will be elicited. There is a rightward displacement of the agonist dose-response curve in the presence of a competitive reversible antagonist, but Emax is not affected.

There is a rightward displacement of the agonist dose-response curve in the presence of a competitive reversible antagonist, but Emax is not affected. Increasing the concentration of antagonist produces a greater rightward displacement of the agonist dose-response curve, and the ED50 value for the agonist increases progressively. However, a maximal effect can always be reached by increasing the dose of agonist. The rightward parallel displacement of the agonist dose-response curves but with preserved Emax is characteristic of competitive reversible antagonism (see Figure 1-3).

Increasing the concentration of antagonist produces a greater rightward displacement of the agonist dose-response curve, and the ED50 value for the agonist increases progressively. However, a maximal effect can always be reached by increasing the dose of agonist. The rightward parallel displacement of the agonist dose-response curves but with preserved Emax is characteristic of competitive reversible antagonism (see Figure 1-3). The magnitude of the rightward displacement of the agonist dose-response curve with increasing antagonist doses is an index of the affinity of the antagonist for the receptor and can be quantified by calculating a dose ratio, calculated as the ED50 in the presence of antagonist divided by the ED50 in the absence of antagonist. The dose ratio is used to calculate a pA2 value, an index of the affinity of the antagonist.

The magnitude of the rightward displacement of the agonist dose-response curve with increasing antagonist doses is an index of the affinity of the antagonist for the receptor and can be quantified by calculating a dose ratio, calculated as the ED50 in the presence of antagonist divided by the ED50 in the absence of antagonist. The dose ratio is used to calculate a pA2 value, an index of the affinity of the antagonist. Competitive irreversible antagonism (also called competitive insurmountable antagonism) (in older literature these are also labeled as noncompetitive antagonists)

Competitive irreversible antagonism (also called competitive insurmountable antagonism) (in older literature these are also labeled as noncompetitive antagonists)

The antagonist competes directly with the agonist for receptor binding as described previously. However, the binding forces between the antagonist and receptor are so strong that the antagonist-receptor complex is virtually irreversible.

The antagonist competes directly with the agonist for receptor binding as described previously. However, the binding forces between the antagonist and receptor are so strong that the antagonist-receptor complex is virtually irreversible. The net effect is that the total number of receptors available to the agonist is permanently reduced (at least until new receptor is synthesized).

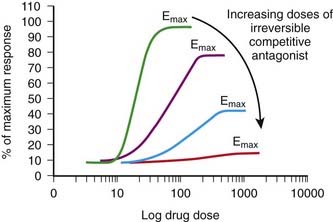

The net effect is that the total number of receptors available to the agonist is permanently reduced (at least until new receptor is synthesized). An important characteristic of this type of antagonism that distinguishes it from competitive reversible antagonism is that Emax is reduced (Figure 1-4).

An important characteristic of this type of antagonism that distinguishes it from competitive reversible antagonism is that Emax is reduced (Figure 1-4). A second distinguishing feature of this type of antagonist is that its effects will be constant irrespective of endogenous agonist levels. Thus fluctuations in the release of transmitter or hormone do not affect the response to this type of antagonist. This type of antagonist is useful clinically in situations in which endogenous agonist levels are unpredictable.

A second distinguishing feature of this type of antagonist is that its effects will be constant irrespective of endogenous agonist levels. Thus fluctuations in the release of transmitter or hormone do not affect the response to this type of antagonist. This type of antagonist is useful clinically in situations in which endogenous agonist levels are unpredictable. Noncompetitive antagonism (also called allotropic or allosteric antagonism)

Noncompetitive antagonism (also called allotropic or allosteric antagonism)

Noncompetitive antagonists do not directly compete with the agonist for binding at the same binding site but nevertheless impair the ability of an agonist to bind to or activate the receptor, and thus they prevent a response.

Noncompetitive antagonists do not directly compete with the agonist for binding at the same binding site but nevertheless impair the ability of an agonist to bind to or activate the receptor, and thus they prevent a response. An important characteristic of this type of antagonism is that both antagonist and agonist can be bound to the molecular target at the same time.

An important characteristic of this type of antagonism is that both antagonist and agonist can be bound to the molecular target at the same time. Because agonists and antagonists bind at distinct sites, increasing concentrations of agonist do not out-compete or reverse the inhibitory action of the antagonist.

Because agonists and antagonists bind at distinct sites, increasing concentrations of agonist do not out-compete or reverse the inhibitory action of the antagonist. Noncompetitive antagonists will exert functional effects similar to those of competitive irreversible antagonists in that both types of antagonist will decrease the Emax or efficacy of the agonist.

Noncompetitive antagonists will exert functional effects similar to those of competitive irreversible antagonists in that both types of antagonist will decrease the Emax or efficacy of the agonist. Because the agonist and antagonist act at different sites on the molecular target, increasing concentrations of agonist cannot overcome the inhibitory action of the antagonist. Thus, the effect of a noncompetitive antagonist will be independent of fluctuations in levels of the endogenous agonist, much like that of a competitive irreversible antagonist.

Because the agonist and antagonist act at different sites on the molecular target, increasing concentrations of agonist cannot overcome the inhibitory action of the antagonist. Thus, the effect of a noncompetitive antagonist will be independent of fluctuations in levels of the endogenous agonist, much like that of a competitive irreversible antagonist. A clinically relevant difference may be in the duration of action. Most allosteric antagonists combine reversibly with their binding site. Accordingly, discontinuation of the drug will result in a decrease in antagonist binding and effect. In contrast, as mentioned earlier, one of the features of competitive irreversible antagonists is their prolonged duration of action.

A clinically relevant difference may be in the duration of action. Most allosteric antagonists combine reversibly with their binding site. Accordingly, discontinuation of the drug will result in a decrease in antagonist binding and effect. In contrast, as mentioned earlier, one of the features of competitive irreversible antagonists is their prolonged duration of action. Clinical Connection: Drugs that bind covalently to their molecular targets have the benefit of extended duration of action. Knowledge of this characteristic can influence clinical application of the drug. Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) irreversibly acetylates and inhibits the cyclooxygenase enzyme present in platelets and thereby inhibits platelet aggregation that contributes to coronary artery occlusion and myocardial infarcts. Although aspirin is cleared relatively quickly from the body, when used for its antiplatelet activity in patients with coronary artery disease, its administration is required only once a day because aspirin does not dissociate from its molecular target when plasma concentrations decrease.

Clinical Connection: Drugs that bind covalently to their molecular targets have the benefit of extended duration of action. Knowledge of this characteristic can influence clinical application of the drug. Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) irreversibly acetylates and inhibits the cyclooxygenase enzyme present in platelets and thereby inhibits platelet aggregation that contributes to coronary artery occlusion and myocardial infarcts. Although aspirin is cleared relatively quickly from the body, when used for its antiplatelet activity in patients with coronary artery disease, its administration is required only once a day because aspirin does not dissociate from its molecular target when plasma concentrations decrease.Molecular Mechanisms Mediating Drug Action

Receptor Coupling and Transduction Mechanisms

Extracellular Transduction Mechanisms

Extracellular enzymes. Drugs acting via this mechanism alter the activity of extracellular enzymes involved in the synthesis or degradation of endogenous signaling molecules. These drugs affect the levels of endogenous compounds that then alter cellular function by acting on their receptors. Examples of clinical utility for this mechanism include:

Extracellular enzymes. Drugs acting via this mechanism alter the activity of extracellular enzymes involved in the synthesis or degradation of endogenous signaling molecules. These drugs affect the levels of endogenous compounds that then alter cellular function by acting on their receptors. Examples of clinical utility for this mechanism include:

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, which prevent the formation of angiotensin II and are used in the treatment of hypertension

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, which prevent the formation of angiotensin II and are used in the treatment of hypertension Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase, which results in increased levels of acetylcholine for the treatment of:

Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase, which results in increased levels of acetylcholine for the treatment of:

Clinical Connection: Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disorder that targets the acetylcholine receptor. Loss of these receptors at the neuromuscular junction leads to muscle weakness. Edrophonium, a drug that inhibits the extracellular enzyme (cholinesterase) that degrades acetylcholine, can be used to confirm the diagnosis of myasthenia gravis. Injection of edrophonium produces a short-lived increase in acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction and an improvement in muscle strength in patients with myasthenia gravis.

Clinical Connection: Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disorder that targets the acetylcholine receptor. Loss of these receptors at the neuromuscular junction leads to muscle weakness. Edrophonium, a drug that inhibits the extracellular enzyme (cholinesterase) that degrades acetylcholine, can be used to confirm the diagnosis of myasthenia gravis. Injection of edrophonium produces a short-lived increase in acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction and an improvement in muscle strength in patients with myasthenia gravis. Direct interaction with endogenous molecules to affect their ability to reach their sites of action. The clearest example of this type of mechanism is the use of monoclonal antibodies to directly target endogenous signaling molecules. An example of this application is the use of a monoclonal antibody to the cytokine tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) (adalimumab) in the treatment of certain autoimmune disorders. Administration of adalimumab binds TNF-α and prevents the cytokine from reaching and activating its receptor.

Direct interaction with endogenous molecules to affect their ability to reach their sites of action. The clearest example of this type of mechanism is the use of monoclonal antibodies to directly target endogenous signaling molecules. An example of this application is the use of a monoclonal antibody to the cytokine tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) (adalimumab) in the treatment of certain autoimmune disorders. Administration of adalimumab binds TNF-α and prevents the cytokine from reaching and activating its receptor.Transmembrane Transduction Mechanisms

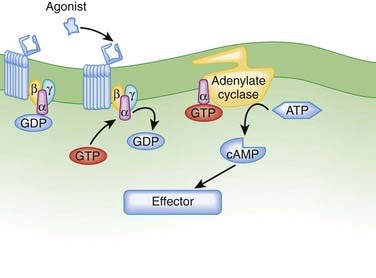

G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs). GPCRs, also called seven transmembrane pass receptors, are a large class of receptors that mediate the majority of endogenous transmitter and hormone driven responses (Figure 1-5).

G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs). GPCRs, also called seven transmembrane pass receptors, are a large class of receptors that mediate the majority of endogenous transmitter and hormone driven responses (Figure 1-5).

Ligand activation of the receptor causes the GPCR to interact with G proteins.

Ligand activation of the receptor causes the GPCR to interact with G proteins.

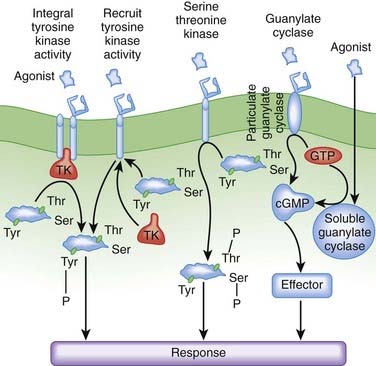

Receptor-coupled enzymes. Receptor-coupled enzymes bypass the G protein coupling mechanism and link directly to cellular communication cascades. The receptor is directly coupled in some way to kinase enzymatic activity within the cell. Ligand binding stimulates the kinase enzymatic activity, which then initiates and amplifies intracellular signals and feedback responses by changing the phosphorylation status of cellular proteins. As shown in Figure 1-6, these mechanisms can be grouped into four general types that include receptors:

Receptor-coupled enzymes. Receptor-coupled enzymes bypass the G protein coupling mechanism and link directly to cellular communication cascades. The receptor is directly coupled in some way to kinase enzymatic activity within the cell. Ligand binding stimulates the kinase enzymatic activity, which then initiates and amplifies intracellular signals and feedback responses by changing the phosphorylation status of cellular proteins. As shown in Figure 1-6, these mechanisms can be grouped into four general types that include receptors:

With guanylate cyclase activity that generate a second messenger, cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)

With guanylate cyclase activity that generate a second messenger, cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)

The receptor-coupled enzymes phosphorylate intracellular proteins at tyrosine (Tyr), serine (Ser), or threonine (Thr) residues to change protein function. Alternatively, cGMP generated by guanylate cyclase activates downstream enzymes (effector in Figure 1-6) that change the phosphorylation status of proteins to alter their function. Receptors with TK activity and guanylate cyclase activity are currently the most clinically useful. Examples of these two receptor-linked enzymes include the following:

Receptors with integral TK activity

Receptors with integral TK activity

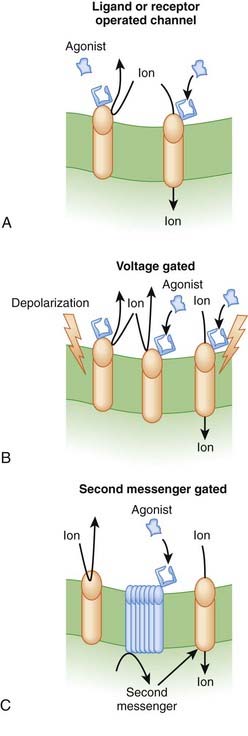

Transmembrane ion channels. Transmembrane ion channels allow the passage of ions from one side of a membrane to another. Channels can exist in the open, closed, or inactive state, which represent different conformations of the channel protein. As shown in Figure 1-7, drugs may affect the function of these channels by directly opening or closing the channel (ligand gated channels), by influencing the voltage-dependent characteristics of the channels (voltage gated channels) and the amount of time the channel spends in a given state, or by generating second messengers that subsequently open or close the channel (second messenger gated). Common examples of functions governed by ion channels include the following:

Transmembrane ion channels. Transmembrane ion channels allow the passage of ions from one side of a membrane to another. Channels can exist in the open, closed, or inactive state, which represent different conformations of the channel protein. As shown in Figure 1-7, drugs may affect the function of these channels by directly opening or closing the channel (ligand gated channels), by influencing the voltage-dependent characteristics of the channels (voltage gated channels) and the amount of time the channel spends in a given state, or by generating second messengers that subsequently open or close the channel (second messenger gated). Common examples of functions governed by ion channels include the following:

Neurotransmission

Neurotransmission

There are several subtypes of ion channels, based on the ways that drugs or endogenous substances regulate the channels (see Figure 1-7).

Ligand gated ion channels or receptor-operated channels. These ion channels possess a receptor for an endogenous ligand to which the drug can bind. They are composed of a multimeric protein complex that constitutes both the receptor and the ion channel. Agonist activation opens the channel, and antagonists close or inactivate the channel. Examples include the following:

Ligand gated ion channels or receptor-operated channels. These ion channels possess a receptor for an endogenous ligand to which the drug can bind. They are composed of a multimeric protein complex that constitutes both the receptor and the ion channel. Agonist activation opens the channel, and antagonists close or inactivate the channel. Examples include the following:

Voltage gated ion channels. These ion channels change conformation (open, closed, or inactive) in response to changes in membrane voltage. Drug binding to the channel alters the response of the channel to changes in membrane voltage such that the open, closed, or inactivate state may be lengthened or shortened. An example is a local anesthetic agent that binds to sodium channels that are responsive to the arrival of an action potential. Local anesthetics lock the channels in the inactive state, thereby rendering them temporarily nonresponsive to future action potentials and thereby block transmission of pain signals.

Voltage gated ion channels. These ion channels change conformation (open, closed, or inactive) in response to changes in membrane voltage. Drug binding to the channel alters the response of the channel to changes in membrane voltage such that the open, closed, or inactivate state may be lengthened or shortened. An example is a local anesthetic agent that binds to sodium channels that are responsive to the arrival of an action potential. Local anesthetics lock the channels in the inactive state, thereby rendering them temporarily nonresponsive to future action potentials and thereby block transmission of pain signals. Second messenger gated ion channels. These ion channels respond directly or indirectly to second messenger molecules (see second messenger section, later, for details). Drug binding to receptor elaborates a second messenger that in turn affects channel function. Examples of clinical utility include the following:

Second messenger gated ion channels. These ion channels respond directly or indirectly to second messenger molecules (see second messenger section, later, for details). Drug binding to receptor elaborates a second messenger that in turn affects channel function. Examples of clinical utility include the following:

Membrane-Bound Transporters

Diuretics. The loop diuretics, a major class of diuretic agents, inhibit the sodium, potassium, two chloride co-transporter in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle, promoting loss of sodium and water in the urine.

Diuretics. The loop diuretics, a major class of diuretic agents, inhibit the sodium, potassium, two chloride co-transporter in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle, promoting loss of sodium and water in the urine.Intracellular Transduction Mechanisms

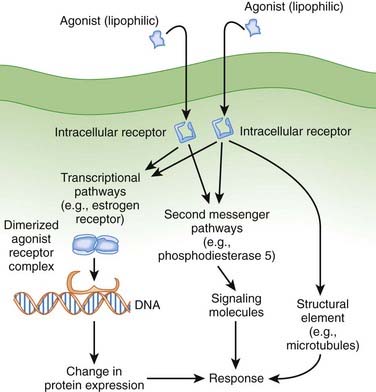

Intracellular Receptors

Lipophilic drugs passively cross the cell membrane and thus do not require cell membrane receptors. As shown in Figure 1-8, one target for these drugs is an intracellular receptor that activates transcriptional pathways. In this mechanism, the agonist receptor complex diffuses to DNA, where it binds to DNA binding elements. Via this mechanism drugs act directly or through recruitment of coactivators or co-repressors, which increase or decrease transcription of RNA to ultimately change protein expression. This process is referred to as ligand gated transcriptional regulation. In many cases these drugs effect long-term changes by affecting gene transcription. Receptors using this coupling mechanism include:

Examples of ligand gated transcription regulation with clinical utility include:

Clinical Connection: Tamoxifen and raloxifene are selective estrogen receptor modulators. Tamoxifen and raloxifene act as antagonists in breast tissue and are useful in the treatment of breast cancer. However, use of tamoxifen is complicated by estrogen receptor agonist activity in the uterus, where the drug triggers an increased risk for uterine cancer. Raloxifene, despite combining to the same receptor, does not exhibit agonist activity in the uterus, and therefore its use is not complicated by concerns about uterine cancer.

Clinical Connection: Tamoxifen and raloxifene are selective estrogen receptor modulators. Tamoxifen and raloxifene act as antagonists in breast tissue and are useful in the treatment of breast cancer. However, use of tamoxifen is complicated by estrogen receptor agonist activity in the uterus, where the drug triggers an increased risk for uterine cancer. Raloxifene, despite combining to the same receptor, does not exhibit agonist activity in the uterus, and therefore its use is not complicated by concerns about uterine cancer.Intracellular Enzymes

Some drugs directly target intracellular enzymes, such as phosphodiesterase (PDE), that control second messenger pathways (see Figure 1-8) and thereby alter the concentrations of intracellular signaling molecules, which then effects a cellular response. As greater understanding of intracellular signaling is achieved, it is likely that more drugs using this mode of action will be developed. Often there are multiple levels of intracellular signaling molecules downstream from the enzyme being targeted. A common example of the utility of this approach is PDE5 inhibition, to prevent the breakdown of cGMP, which results in increased vasodilation. This approach is useful in the treatment of erectile dysfunction because of the ability to somewhat selectively target blood vessels in the penis.

Structural Mechanisms

Drugs can also target structural components of cells (e.g., the cytoskeleton or microtubules) to affect their function (see Figure 1-8). Examples of clinical utility include the following:

Vinca alkaloids (e.g., vincristine) disrupt microtubule formation and arrest cell division and are used in cancer chemotherapy.

Vinca alkaloids (e.g., vincristine) disrupt microtubule formation and arrest cell division and are used in cancer chemotherapy.Second Messenger Systems

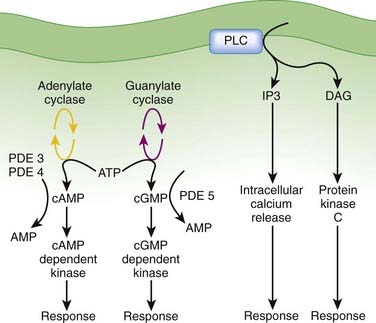

After formation of the drug-receptor complex and activation of a coupling mechanism (e.g., G proteins), the drug signal is transmitted to the final effector system of the cell. In many cases the transduction or coupling mechanism is linked to the final effector system via an intermediate cell signaling (second messenger) system. Drugs may also target enzymes or other processes regulating the concentrations of intracellular second messengers. This represents an important mode of drug action. In addition, it opens the possibility for synergistic or antagonist interactions among drugs that act at different sites in the same pathway. These interactions may enhance therapeutic effects or lead to adverse effects. The field of cell signaling is extremely dynamic, with new signaling molecules or new functions for established molecules discovered on a seemingly daily basis. Therefore, it is not possible to discuss the intricacies of all second messenger systems linked to clinically relevant drug actions. Nevertheless, several pathways serve as good illustrations of the involvement of cell signaling mechanisms as mediators of drug responses and as targets for future drug development. Figure 1-9 illustrates three of the best understood second messenger systems.

Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate Pathway

Adenylate cyclase is modulated by activated Gα-GTP complexes in either a stimulatory (Gαs-GTP) or inhibitory (Gαi-GTP) fashion.

Adenylate cyclase is modulated by activated Gα-GTP complexes in either a stimulatory (Gαs-GTP) or inhibitory (Gαi-GTP) fashion. Multiple isoforms of adenylate cyclase show isoform-specific interactions with Gα-GTP and tissue-specific distribution.

Multiple isoforms of adenylate cyclase show isoform-specific interactions with Gα-GTP and tissue-specific distribution. Agonists activating adenylate cyclase may elicit differential responses in different target tissues.

Agonists activating adenylate cyclase may elicit differential responses in different target tissues. cAMP signaling can proceed through:

cAMP signaling can proceed through:

cAMP-dependent protein kinases triggering phosphorylation of effector molecules (e.g., cardiac voltage gated calcium channel) to elicit short-term effects

cAMP-dependent protein kinases triggering phosphorylation of effector molecules (e.g., cardiac voltage gated calcium channel) to elicit short-term effectsCyclic Guanosine Monophosphate

Production of cGMP through activation of guanylate cyclase, which can be:

Production of cGMP through activation of guanylate cyclase, which can be:

Activation of guanylate cyclase leads to increased cGMP as a second messenger molecule that activates downstream cGMP-dependent kinases to cause phosphorylation of effector systems. An important effector system is the contractile apparatus of vascular smooth muscle, where cGMP phosphorylation leads to vasodilation.

Activation of guanylate cyclase leads to increased cGMP as a second messenger molecule that activates downstream cGMP-dependent kinases to cause phosphorylation of effector systems. An important effector system is the contractile apparatus of vascular smooth muscle, where cGMP phosphorylation leads to vasodilation. PDEs also play a critical role as an off switch for this pathway. Accordingly, PDE inhibitors are used to interact with this signaling pathway. The development of drugs that selectively inhibit PDE5 (e.g., sildenafil), which is selective for cGMP, revolutionized the treatment of erectile dysfunction by improving penile blood flow.

PDEs also play a critical role as an off switch for this pathway. Accordingly, PDE inhibitors are used to interact with this signaling pathway. The development of drugs that selectively inhibit PDE5 (e.g., sildenafil), which is selective for cGMP, revolutionized the treatment of erectile dysfunction by improving penile blood flow.Phospholipase C, Inositol 1,4,5 Trisphosphate (IP3), Diacylglycerol (DAG)

DAG activates the protein kinase C (PKC) family of enzymes.

DAG activates the protein kinase C (PKC) family of enzymes.

Activation may be isoform and tissue specific.

The IP3-DAG-PKC pathway is very widespread and linked to many functions. This signaling mechanism is coupled to receptors for some of the major homeostatic pathways, including α-adrenergic receptors, serotonin receptors, angiotensin receptors, acetylcholine receptors, and prostaglandins, to name but a few. The widespread nature of this pathway makes it very important but also very difficult to manipulate to achieve selective therapeutic actions with minimal side effects. Nevertheless, this is an area of ongoing research, and isoform-specific inhibitors of PKC are in development for clinical applications. Enzastaurin, a selective PKC-β isoform inhibitor, is in clinical trials as an antineoplastic agent.

The IP3-DAG-PKC pathway is very widespread and linked to many functions. This signaling mechanism is coupled to receptors for some of the major homeostatic pathways, including α-adrenergic receptors, serotonin receptors, angiotensin receptors, acetylcholine receptors, and prostaglandins, to name but a few. The widespread nature of this pathway makes it very important but also very difficult to manipulate to achieve selective therapeutic actions with minimal side effects. Nevertheless, this is an area of ongoing research, and isoform-specific inhibitors of PKC are in development for clinical applications. Enzastaurin, a selective PKC-β isoform inhibitor, is in clinical trials as an antineoplastic agent. Clinical Connection: Knowledge of coupling and second messenger systems can help in understanding drug interactions. Nitrates used in the treatment of coronary ischemia stimulate guanylate cyclase to produce cGMP. PDE5 inhibitors used in the treatment of erectile dysfunction inhibit the breakdown of cGMP. Concurrent use of these two drugs can lead to excessive levels of cGMP, which in turn cause excessive vasodilation and potentially dangerous reductions in blood pressure. Consequently, patients are warned to not use PDE5 inhibitors if they are on nitrate therapy for angina.

Clinical Connection: Knowledge of coupling and second messenger systems can help in understanding drug interactions. Nitrates used in the treatment of coronary ischemia stimulate guanylate cyclase to produce cGMP. PDE5 inhibitors used in the treatment of erectile dysfunction inhibit the breakdown of cGMP. Concurrent use of these two drugs can lead to excessive levels of cGMP, which in turn cause excessive vasodilation and potentially dangerous reductions in blood pressure. Consequently, patients are warned to not use PDE5 inhibitors if they are on nitrate therapy for angina.Amplification of Drug Responses

Amplification is an important component of pharmacologic responses. A great deal of amplification occurs in pharmacologic pathways, such that only a minute quantity of drug (often in the picomolar or femtomolar range) is capable of eliciting biologic responses. In general, only minute concentrations of neurotransmitters, hormones, or exogenously administered drugs need reach the molecular target to initiate a biologic response. This exquisite sensitivity of tissues to drugs results in large part from amplification of the original signal provided by the drug molecule. Amplification can occur at several points in the drug-receptor coupling and signaling systems (Figure 1-10).

Receptor

Receptor

Increases or decreases in receptor expression will increase or decrease, respectively, tissue sensitivity to the agonist because of the law of mass action.

Increases or decreases in receptor expression will increase or decrease, respectively, tissue sensitivity to the agonist because of the law of mass action. Many tissues express more receptors than are necessary to elicit a full response (spare receptors). This concept is called spare receptors or receptor reserve.

Many tissues express more receptors than are necessary to elicit a full response (spare receptors). This concept is called spare receptors or receptor reserve.Factors Modifying Drug Responses

Changes in the amount of drug at the intended molecular target

Changes in the amount of drug at the intended molecular target

Polymorphisms in drug absorption, distribution, or metabolism are major causes of interindividual variability.

Polymorphisms in drug absorption, distribution, or metabolism are major causes of interindividual variability. Changes in the drug receptor itself

Changes in the drug receptor itself

Different patients express differing numbers or composition of receptors (receptor polymorphisms), leading to differences in affinity or efficacy of the drugs they bind (see Chapter 6, on pharmacogenomics).

Different patients express differing numbers or composition of receptors (receptor polymorphisms), leading to differences in affinity or efficacy of the drugs they bind (see Chapter 6, on pharmacogenomics). Changes in coupling or signaling mechanisms

Changes in coupling or signaling mechanisms

Homologous desensitization or tolerance is specific to one receptor type or drug class.

Heterologous desensitization or tolerance affects many receptor types or drugs.

Clinical Connection: Nitrates are used extensively in the treatment of coronary ischemia. Continuous administration of nitrates is known to produce a reduction in drug response. In some patients, this can occur in as little as 24 hours. Accordingly, the drug regimen for patients taking nitrates includes a daily nitrate-free period or drug holiday of approximately 8 hours each day. Such intermittent administration prevents the development of nitrate tolerance.

Clinical Connection: Nitrates are used extensively in the treatment of coronary ischemia. Continuous administration of nitrates is known to produce a reduction in drug response. In some patients, this can occur in as little as 24 hours. Accordingly, the drug regimen for patients taking nitrates includes a daily nitrate-free period or drug holiday of approximately 8 hours each day. Such intermittent administration prevents the development of nitrate tolerance.