Autonomic dysreflexia

Pathophysiology

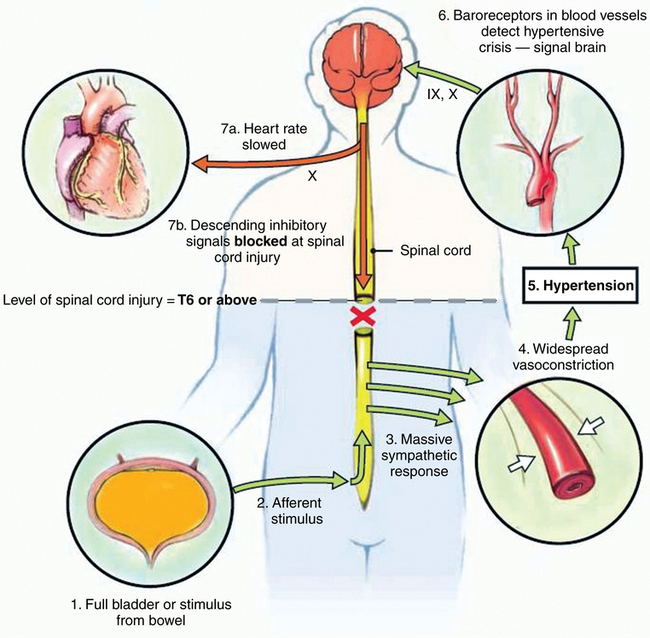

AD results from unopposed sympathetic efferent outflow in response to noxious afferent input below the level of the spinal cord injury, with reflex activation of parasympathetic outflow above the T6 dermatomal level. The pathways involved are summarized in Figure 178-1.