Choledochoceles: Are They Choledochal Cysts?

Choledochal cysts are abnormal dilatations of the biliary tree, generally believed to be congenital in origin. Choledochal cysts are more common in Asian populations (reported incidence of 1 in 1000) than in the Western hemisphere, where the incidence is only 1 in 100,000 to 150,000 live births [1]. Despite their rarity, choledochal cysts represent an important biliary condition, because this disease must be recognized and treated appropriately to prevent the development of biliary malignancy [2,3]. Several subtypes of choledochal cysts have been described, including the choledochocele, which is an abnormal dilatation of the distal common bile duct within the ampulla of Vater. The purpose of this review is to contrast the natural history of choledochoceles and choledochal cysts.

Choledochal cysts and choledochoceles: accepted classification

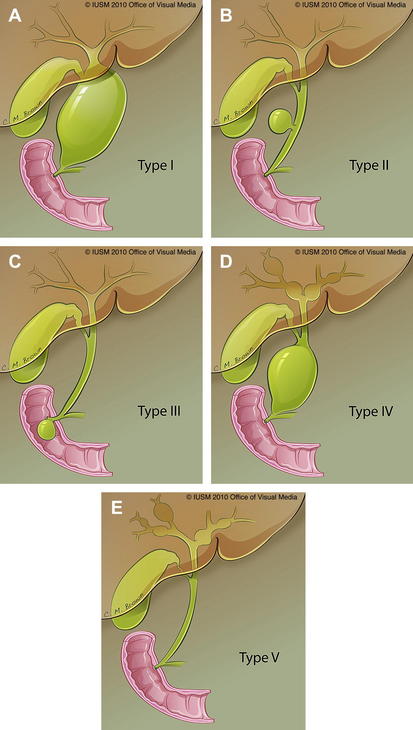

Historically, choledochal cysts have been classified according to the descriptions published in 1959 by Alonso-Lej [4], with subsequent modifications. Alonso-Lej identified 3 types of choledochal cysts: the first type was a segmental cystic dilation of the common bile duct (CBD), the second a solitary CBD diverticulum, and the third a bulbous dilation of the distal-most portion of the CBD within the ampulla of Vater (choledochocele). This classification system has been modified by numerous investigators, including Longmire and colleagues [5] in 1971 and Todani and colleagues [2] in 1977. Todani’s modifications included subdividing type I cysts into (1) saccular, (2) segmental, and (3) diffuse. In addition to types I, II, and III, Todani also included type IV choledochal cysts, which are multiple and usually involve the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary system, and type V, intrahepatic bile duct cysts or Caroli disease (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 (A–E) Choledochal cysts according to Todani’s modification of Alonso-Lej’s original scheme.

(Data from Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, et al. Congenital bile duct cysts: classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg 1977;134(2):263–9; and Alonso-Lej F, Rever W, Pessango D. Congenital choledochal cyst, with a report of 2, and analysis of 94 cases. Int Abstr Surg 1959;108(1):1–30.)

Since the time of Todani’s modifications, numerous surgical series have been published describing choledochal cysts, along with their relative frequencies, pathophysiology, and propensity for malignant degeneration. Choledochoceles (type III choledochal cysts) are only rarely included in these series because they comprise only 1% to 4% of all reported choledochal cysts [3,6]. Thus the natural history of choledochoceles has not been well characterized. Our group recently collected a combined surgical and endoscopic series of 146 patients with choledochal cysts including 28 choledochoceles, the largest single-institution Western series published to date [7]. In this series, choledochoceles were compared with choledochal cysts in terms of patient demographics, presenting symptoms, radiologic studies, associated abnormalities, and surgical and endoscopic procedures, as well as outcomes. Our analysis suggested that choledochoceles may have a discrete natural history compared with choledochal cysts.

Choledochoceles

Choledochoceles are dilatations of the distal CBD within the ampulla of Vater (Fig. 2). Choledochoceles are the rarest type of choledochal cysts, representing 1% to 4% of all reported cases [3]. The term choledochocele first appeared in a 1940 report from Wheeler [8], who described a case of biliary obstruction secondary to a dilated intraduodenal portion of the CBD, likening this situation to a similar phenomenon in the ureter (ureterocele). Only 4 choledochoceles were included in the publication of 94 choledochal cysts by Alonso-Lej in 1959 [4]. Even then, he questioned “as to whether or not it (choledochocele) originates from the same etiologic factors (as other choledochal cysts).” Subsequent investigators continued to question the relationship between choledochoceles and other choledochal cysts, including Trout and Longmire in 1971 [9], and many others over the following decades [10–16]. Choledochoceles continue to be a rare and poorly understood entity, with fewer than 200 cases reported in the English literature [15,17–19].

Fig. 2 Endoscopic view of choledochocele (type III choledochal cyst).

(From Ziegler KM, Pitt HA, Zyromski NJ, et al. Choledochoceles: are they choledochal cysts? Ann Surg 2010;252(4):683–90; with permission.)

The cause of choledochoceles and choledochal cysts is incompletely understood. The concept that choledochal cysts types I, II, IV, and V are congenital in nature is generally accepted. In contrast, several investigators have suggested that choledochoceles may be acquired [12,13,18,20]. In addition, choledochoceles may be lined with duodenal mucosa, and the potential for malignancy is reported to be significantly lower than in other types of choledochal cysts [15,19–21]. This decreased risk of biliary malignancy in combination with their accessible anatomic location has led to a shift in the management of choledochoceles from surgical to endoscopic therapy [17,19,22–25]. Some investigators have noted these dissimilarities between choledochoceles and choledochal cysts [12–16], but until recently, large series of surgical and endoscopic patients with choledochoceles have not been available.

Pathophysiology

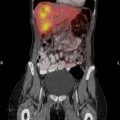

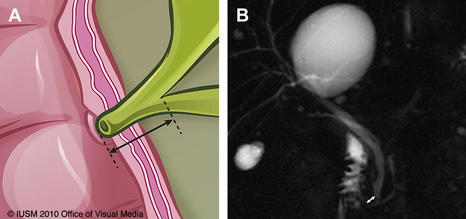

Several theories exist regarding the cause of the various types of choledochal cysts. The fact that choledochal cysts are often diagnosed in infants supports the hypothesis that they are congenital in nature [26–28]. However, choledochal cysts are also postulated to be the result of another congenital anomaly, the anomalous pancreatobiliary duct junction (APBDJ). The anatomy of the biliopancreatic ductal system is notoriously variable. An APBDJ has been defined as insertion of the bile duct greater than 15 mm proximal to the ampulla of Vater (Fig. 3). The relationship between APBDJ and choledochal cyst formation was first described by Babbitt in 1969 [29]. He postulated that reflux of pancreatic juice into the CBD resulted in the cystic dilation of the duct. Embryologic data published by Wong and Lister [30] suggest that APBDJ results from failure of inward migration of the choledochopancreatic junction, leading to weakness in the wall of the bile duct. Since this time, the association between APBDJ and choledochal cysts has been well documented by several investigators [26,31,32]. APBDJ has generally not been observed in choledochoceles, which are less frequently associated with congenital biliopancreatic duct junction abnormalities [15,16].

Fig. 3 (A) APBDJ. (B) Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image illustrating APBDJ (white arrow).

In our series, 83% of choledochal cysts were associated with an APBDJ. In contrast, only 5 junction abnormalities were described in the 28 patients with choledochocele, and this description may have been referring to the cystic dilation of the choledochocele itself, which often contains the termination of the bile duct and thus creates an abnormal-appearing common channel [7]. Although not occurring in conjunction with APBDJ, an increased incidence of pancreas divisum was seen in patients with choledochoceles in our series compared with those with choledochal cysts (37% vs 7%, P<.05), which is a unique observation. The low incidence of pancreas divisum in choledochal cysts has been reported [33–37], but limited data on pancreas divisum in patients with choledochoceles are available [19,34–38].

Another clue in determining the pathophysiology of choledochoceles, in contrast to choledochal cysts, is the observation that choledochoceles are seen with increased frequency in patients who have undergone previous cholecystectomy [19,39,40]. Our recent series showed that 44% of patients had previously had a cholecystectomy [7], similar to other reports from combined case series [12,40]. The finding that choledochoceles often occur in the setting of increased sphincter pressure brings into question the pathophysiology of their development. Thus, whereas choledochal cysts are generally accepted as congenital anomalies, many investigators postulate that choledochoceles may be acquired [12,18,20,23,25].

Demographics and presenting symptoms

The method of presentation differs significantly between choledochoceles and choledochal cysts. Classically, choledochal cysts are found most commonly in female children; in contrast, patients with choledochoceles are more likely to be older and are more frequently male [11,39,40]. Our recent series showed the average age at presentation to be significantly greater in patients with choledochoceles compared with other cyst types (50.7 years vs 29 years). We did not observe the typical female predominance (57% vs 81% female) [7]. A review of all the Japanese and Western patients with choledochocele in 1994 (n = 109) also reported a lack of gender prevalence and older average age [18].

Patients with choledochal cysts typically present with pain and biliary tract symptoms, such as jaundice or cholangitis. The classic triad of abdominal pain, jaundice, and right upper quadrant mass is of historical importance, but is infrequently documented in modern series [3,41]. Several investigators have observed that symptoms also differ depending on the patient’s age at presentation: adults are more likely to present with pain, cholangitis, and/or malignancy, and children more likely to present with jaundice and/or abdominal mass [6,32,42]. Compared with those with choledochal cysts, patients with choledochoceles are more likely to present with pancreatitis and less likely to present with biliary tract symptoms [18,23,25,43]. Among patients with choledochoceles, Sarris and Tsang [40] reported a pancreatitis rate of 38%, as did Masetti and colleagues [17] in a large review. Our series of 146 patients showed a 48% rate of pancreatitis in patients with choledochoceles compared with only 24% in patients with choledochal cysts [7]. Conversely, the incidence of cholangitis was zero in patients with choledochoceles, whereas 21% of patients with choledochal cyst had cholangitis.

Diagnostic evaluation

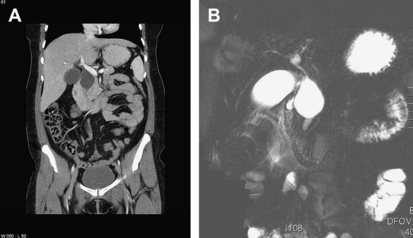

The diagnosis of choledochal cysts and choledochoceles has evolved over time. The increased use of abdominal imaging as well as the widespread availability of endoscopic evaluation have both improved our ability to characterize these lesions. In the early twentieth century, cystic biliary lesions were commonly identified by open surgical exploration [4,8] or by intravenous cholangiography [44,45]. Modern available technologies include ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT) scanning, nuclear medicine hydroxyimidoacetic acid scanning, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with or without magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), endoscopic ultrasound, and prenatal ultrasonography. Fig. 4 shows characteristic findings of choledochoceles imaged with various modalities. Most investigators recommend tailoring these modalities to each patient’s symptoms and clinical conditions, with additional care to avoid unnecessary invasive testing in infants and young children. In most series, ultrasonography is the most commonly used method of diagnosis in children, because of its higher sensitivity (97%) in this population versus adults [6,42,46]. In adults, some controversy exists as to the official gold standard in diagnosis of choledochal cysts, because various combinations of CT, PTC, ERCP, and MRCP are frequently used [6,41,42,47]. In many cases, more than 1 imaging study provides complementary information. Moreover, as abdominal imaging and ERCP become more common, choledochal cysts are diagnosed with increasing frequency in patients who are asymptomatic, leading to further controversies in their management [48].

The diagnosis of choledochoceles differs from that of choledochal cysts in that most choledochoceles are identified using ERCP (Fig. 5) [17,25]. This trend was also seen in our recent series, with a rate of ERCP of 82% among patients with choledochocele and only 61% among other cyst types [7]. This finding is likely caused by the common presenting symptoms of choledochoceles (abdominal pain and recurrent pancreatitis), a constellation of symptoms that typically leads to endoscopic evaluation.

Ductal anatomic abnormalities

As mentioned earlier, a significant number of patients with choledochal cyst have APBDJ. The incidence of APBDJ in patients with choledochal cyst ranges from 50% to 80% [1]. The true incidence of APBDJ is unknown because not all patients with this anatomy undergo standardized imaging. Expert pancreatobiliary radiologists concur that MRI/MRCP may be the best single test with which to accurately determine length of the common biliopancreatic channel [49]. Nevertheless, biliopancreatic duct length is important in distinguishing true choledochal cysts from benign dilatation of the bile duct as a result of other causes (eg, in the elderly patient, after cholecystectomy).

Associated neoplasia

Choledochal cysts are associated with a lifetime incidence of biliary malignancy of about 10% (range 2.5%–50%). Recent series highlight variability in malignancy depending on whether the patient undergoes appropriate treatment, and the age at which that treatment occurs [47,50–54]. Carcinoma of the gallbladder occurs with nearly the same frequency as cholangiocarcinoma in patients with choledochal cysts.

The pathogenesis leading to the development of cholangiocarcinoma in these patients is believed to be related to the reflux of pancreatic juice into the biliary tract as a result of the APBDJ. These pancreatic enzymes are then activated, leading to inflammation, proliferation, and hyperplasia of the biliary mucosa, which leads to dysplasia and finally carcinoma [47,54,55]. Support for this theory lies in the fact that APBDJ leads to an increased risk of biliary malignancy in patients without choledochal cysts [31,55]. Thus, it should not be surprising that the incidence of biliary malignancy in patients with choledochoceles (which are typically not associated with APBDJ) is lower than in those with choledochal cysts. Although ampullary carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma may arise in conjunction with a choledochocele, fewer than 10 such cases have been reported [15,19,21,39,40]. In our series of 146 patients, only 6 patients had malignant neoplasms: 1 pancreatic carcinoma in a patient with a choledochocele, 1 biliary rhabdomyosarcoma in a child with a type IV choledochal cyst, and 4 patients with type I cyst (3 with cholangiocarcinoma and 1 who developed ampullary carcinoma) [7]. Pancreatic cancer in association with a choledochocele has been reported [56], but no clear association has yet been established.

Endoscopic, percutaneous, and surgical management

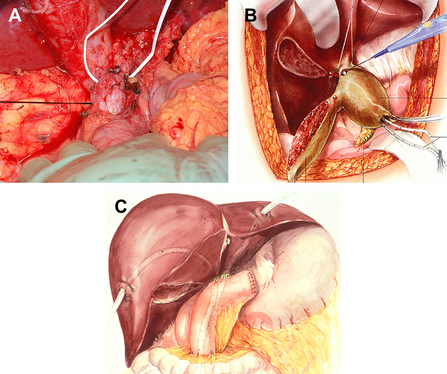

The relative decreased incidence of biliary malignancy in patients with choledochocele compared with those with choledochal cysts influences what is perhaps the most prominent difference between the 2 entities: their management. Extrahepatic choledochal cysts are best managed surgically, with complete resection of the cyst, gallbladder, and extrahepatic biliary tree, with hepaticojejunostomy reconstruction (Fig. 6) [57–61]. Management of intrahepatic choledochal cysts varies depending on the extent of liver involvement, and ranges from intrahepatic hepaticojejunostomy with stenting to formal liver resection to transplantation (the latter for true type V choledochal cyst) [57,61–63]. Internal drainage and partial excisions of choledochal cysts deserve mention from a historical perspective, but have been abandoned because of the high rate of cholangiocarcinoma developing in the cyst remnant or the bile duct [50,64–66]. Furthermore, as minimally invasive techniques evolve, many centers including our own are now performing choledochal cyst excisions with hepaticojejunostomy/hepaticoduodenostomy using a laparoscopic approach [67,68].

The appropriate management of choledochoceles is less well defined, likely because of their rarity and the small numbers of choledochoceles in most surgical series of choledochal cysts. Excision of choledochoceles (with either pancreatoduodenectomy or transduodenal excision with sphincteroplasty) [57,63,69] and surgical unroofing with sphincteroplasty [43,70] have been described; most modern series report successful treatment of choledochoceles with endoscopic techniques. Endoscopic management of choledochoceles with endoscopic sphincterotomy was first described in 1981 [71] and has been accepted as the standard of care at many centers by endoscopists and surgeons alike [17,19,22–25]. Our series includes 28 patients with choledochoceles, 86% of whom underwent ERCP (vs 64% of patients with choledochal cyst), and 79% of patients with choledochocele were managed definitively with endoscopic therapies (sphincterotomy, with or without biliary/pancreatic stent placement), whereas 80% of choledochal cysts were managed definitively with surgery. Only 3 patients with choledochoceles were managed surgically: 2 pediatric patients who underwent transduodenal sphincteroplasty, and 1 adult patient who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy for complications of chronic pancreatitis.

Although the available literature indicates that endoscopic therapy leads to resolution of symptoms in most patients with choledochoceles, few long-term follow-up studies have addressed the risk of malignancy in these patients [22]. Clues to the potential risk of developing malignancy in choledochoceles may include several variable characteristics of the choledochoceles themselves: ductal configuration and histologic lining. Several investigators have noted several possible configurations of choledochoceles, although official subtypes have not been established. In 1 type, both the CBD and the pancreatic duct drain into the choledochocele, forming a very dilated common channel. In the other type, the dilation is limited to the distal CBD, which then either drains directly into the duodenum or joins with the pancreatic duct just proximal to the ampulla, forming a relatively normal common channel [15,21,40,43,45]. In theory, it is the mixing of amylase with bile in the biliary tree that initiates the cascade of carcinogenesis, thus the configuration in which the bile duct and pancreatic duct form a common channel and allow for the reflux of amylase into the bile duct, which theoretically portends a higher risk of neoplasia [12,15]. In addition to variants of anatomic configuration, choledochoceles can be lined with either duodenal or biliary mucosa [10–12,18,21,23,40,43]. Although histologic evaluation of choledochocele mucosa is not always performed, in those studies in which it has been assessed, roughly two-thirds of choledochoceles contain duodenal mucosa, whereas one-third have biliary mucosal lining [12,23,40]. The differential propensity toward cancer based on the type of mucosa has not been adequately studied, but it is tempting to speculate that mucosal composition contributes to the risk of malignant degeneration.

Outcomes

Patients with choledochoceles generally have favorable short-term and long-term outcomes, whether they are treated surgically or endoscopically [19,22]. For example, Ng and colleagues [22] followed 6 patients with choledochocele for 8 to 13 years after sphincterotomy; none developed malignancy. In our series, the mean follow-up time for patients with choledochocele who were managed nonoperatively was 32 months; no malignancies were identified during this follow-up period. However, small numbers of patients and inconsistent follow-up leave many questions unanswered. The need for postsphincterotomy surveillance of aberrant mucosa for malignancy is still unclear, as is the role of surgery in patients who have choledochocele-associated pancreatitis.

Summary

The classification of choledochoceles as a type of choledochal cyst stems from the 1959 article by Alonso-Lej and colleagues [4] describing 94 choledochal cysts, only 4 of which were choledochoceles. Even then, Alonso-Lej questioned the propriety of including the choledochocele, stating it was unclear “as to whether or not it originates from the same etiologic factors [as other choledochal cysts]”. In 1971, Trout and Longmire [9] also questioned the validity of classifying choledochoceles as choledochal cysts, noting the anatomic position and variant mucosa of the choledochocele. Wearn and Wiot [11], in an article titled “Choledochocele: not a form of choledochal cyst”, cite the differences in clinical presentation, demographics, and histology as reasons why choledochoceles represent separate entities from choledochal cysts. Over the ensuing decades, numerous investigators have questioned the legitimacy of classifying choledochoceles as choledochal cysts [10,12–16].