Oral Antibiotics to Prevent Surgical Site Infections Following Colon Surgery

For more than two centuries, surgeons have been performing operations on the colon and rectum. This year more than 100,000 colorectal operations will be performed in the United States alone [1]. Despite the abundant collective knowledge and experience of generations of surgeons, colon operations continue to carry significant risks. Contemporary mortality rates range from 1% to 2% for elective colorectal procedures [2]. Surgical site infections (SSIs), one of many sources of postoperative morbidity, occur in nearly 10% of patients [2]. The authors’ experience with the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative (MSQC) has shown that the range of morbidity rates across centers is broad, some centers achieving rates 50% better than the average. While the etiology of this variation in morbidity is likely multifactorial, it may be explained in part by difference in practice patterns. Among the many aspects of the practice of colon surgery that merit examination, preoperative bowel preparation has been the subject of particular and long-standing controversy. Further investigation, informed by the body of data amassed over the past 50 years, has the potential to define the optimal preoperative bowel preparation, and so reduce the morbidity of colorectal surgery.

Theory

Surgeons have long believed that wound contamination by colonic stool and bacteria contributes to the development of postoperative infection. While it is intuitive that exposure of the peritoneum and incision to fecal pathogens is an infectious risk, bacteriologic and clinical data have also accumulated in support of this notion. Clean operations carry a markedly lower risk of wound infection than clean-contaminated or contaminated procedures in which the peritoneum is exposed to the contents of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Isolates from such wound infections reveal primarily fecal organisms [3].

Accordingly, surgeons have taken measures to decrease the stool and bacterial burden of the colon prior to operation. Mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) is the primary means of reducing colonic fecal content, but does not significantly reduce bacterial concentrations [4]. Orthograde bowel irrigation may be accomplished with large-volume electrolyte solutions, osmotic load, or promotility agents. Retrograde evacuation of the colon and rectum with enemas may complement an oral regimen or serve as stand-alone therapy. Oral antibiotics are added to diminish the bacterial burden in the colon.

Conversely, MBP has multiple potential disadvantages. Liquid colon contents after MBP may actually be more prone to intraoperative spillage than solid stool [5]. Structural and inflammatory changes within the bowel wall have been attributed to MBP, but only inconsistently demonstrated in studies [6–8]. Compromised integrity of the bowel wall or mucus barrier may contribute to anastomotic leak, bacterial translocation, and postoperative ileus. Alteration in colonic flora by oral antibiotics has the potential to exacerbate these effects, and could be associated with complications such as Clostridium difficile colitis. Furthermore, oral irrigating agents are associated with acid-base imbalance, electrolyte derangements, and hypovolemia, all of which are particularly problematic in elderly patients. Finally, MBP is a source of significant patient discomfort, often causing vomiting, diarrhea, bloating, and cramping.

History

The discovery of penicillin in 1929 and its subsequent introduction into clinical practice generated interest in the use of antibiotics to prevent as well as treat SSIs. Surgeons rapidly adapted these concepts to colorectal operations, where septic complications occurred in more than 3 out of 4 patients [9,10]. Attempts were made to sterilize the colonic lumen with an oral antibiotic prior to surgery in hopes of preventing postoperative infection. Early antibiotics were not well suited to this purpose, primarily due to an inadequate spectrum of activity against colonic flora and the development of resistant organisms. Nonetheless the theory endured, and surgeons continued to seek a suitable antibiotic.

One such surgeon enumerated the properties that would characterize the ideal antibiotic for oral prophylaxis in colon surgery [10]. A suitable antibiotic would rapidly eradicate colonic microbes without promoting overgrowth of resistant organisms or impeding anastomotic healing. It would be well tolerated by patients and poorly absorbed, with few systemic effects (Box 1) [10]. Following its introduction in 1949, neomycin was recognized as a strong potential candidate antibiotic [11]. Laboratory and clinical evaluation revealed limited systemic absorption with excellent efficacy against colonic gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria [11–13]. Case series and small trials documented low rates of septic complications and adequate patient tolerance of the regimen [11–16]. Combination regimens including nystatin or sulfa-based antibiotics were also investigated, with favorable results [13]. Although these early reports were promising, concern for the risk of antibiotic-associated Staphylococcus aureus enterocolitis prevented the establishment of oral prophylactic antibiotics as a preoperative standard [17].

Box 1 Ideal characteristics of an oral prophylactic antibiotic for colon surgery

Data from Poth EJ. Historical development of intestinal antisepsis. World J Surg 1982;6(2):153–9.

In 1972, this standard was called into question when Nichols and colleagues [18] published a prospective, randomized, controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of different preoperative bowel preparation regimens. Comparison of microbial burden in the GI tract revealed significantly lower bacterial counts in patients receiving MBP with neomycin and erythromycin than those receiving other antibiotic combinations, MBP alone, or no bowel preparation. The same investigators subsequently demonstrated a reduction in postoperative wound infections for patients treated with a combination of MBP and neomycin-erythromycin before elective colon resection (Box 2) [19]. The rate of SSI was reduced from nearly 20% in patients receiving MBP alone to 0% of 69 patients receiving neomycin-erythromycin, without evidence of staphylococcal or other bacterial overgrowth [19]. Results from these trials prompted a renewed interest in oral antibiotics as an adjunct to MBP.

Box 2 Nichols preoperative bowel preparation

Data from Nichols RL, Broido P, Condon RE, et al. Effect of preoperative neomycin-erythromycin intestinal preparation on the incidence of infectious complications following colon surgery. Ann Surg 1973;178(4):453–62.

Over the course of the following decade, the superiority of MBP with appropriate oral antibiotics was confirmed in other studies, including several multicenter randomized trials [3,9,20–24]. Improvements were documented in the rates of general infectious complications, SSI, abscess, and anastomotic leak. These findings firmly established MBP with oral antibiotics as the gold-standard preparation for elective colon resection.

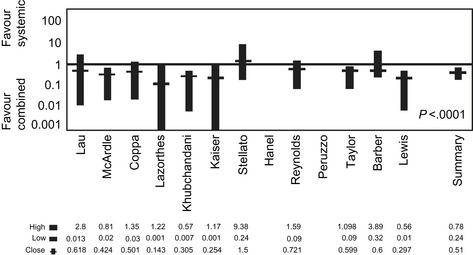

Investigation of systemic antibiotics for prophylaxis in colon surgery occurred in parallel with research on oral antibiotics. Early trials of intravenous systemic antibiotics in the 1950s failed to definitively establish a significant difference in infectious complications [25]. In hindsight, this lack of benefit was likely a result of postoperative rather than preoperative antibiotic administration. A decade later, systemic antibiotics were reevaluated. Using perioperative dosing, prophylactic intravenous antibiotics covering intestinal flora were found to significantly decrease the risk of SSI in GI tract operations [26]. Comparison of colon surgery with systemic versus oral prophylactic antibiotics demonstrated the lowest morbidity rates in patients receiving a combination of both (Fig. 1) [27,28]. The use of combination oral and systemic antibiotic prophylaxis led to renewed interest in the risk of antibiotic-associated colitis such as that caused by C difficile overgrowth. An actual increase in the risk of C difficile colitis with combination regimens has been reported only in select studies [29,30]. Nonetheless, concern over C difficile, coupled with surgeon confidence in the efficacy of systemic antibiotics, generated a reluctance to use combination prophylaxis. Consequently, the use of oral antibiotics declined.

In 1987, the entire practice of preoperative bowel preparation was abruptly called into question. Irving and Scrimgeour [31] described 73 patients who underwent elective colorectal operations with a single dose of preoperative systemic antibiotics, but no MBP or oral antibiotics. The overall rate of wound infection was 8%, which compared favorably with rates reported by other investigators who did use MBP. According to one of their contemporaries, this was “stirring stuff, terse and derisive… a veritable little bomb of a paper, brief, iconoclastic, disrespectful of hallowed tradition in colorectal surgery” [32]. Certainly it provoked more than 20 years of debate surrounding the appropriate preoperative management of colorectal surgery patients. Despite numerous prospective randomized trials, the controversy endures.

Current state of the literature

Since the landmark article by Irving and Scrimgeour in 1987 [31], there have been multiple studies seeking to establish the ideal preoperative management of colorectal surgery patients. More than 15 randomized controlled trials have compared MBP (without oral antibiotics) with no bowel preparation prior to elective colon and rectal surgery [33–48]. The majority found no significant difference between the two groups in mortality, infectious complications, or anastomotic leak [35,37,39–41,43,46–49]. In the largest study, a multicenter randomized controlled trial of more than 1500 patients, complications were documented in 24.5% of patients who underwent MBP compared with 23.7% of patients who did not. Similarly, the rates of infectious, surgical site, and cardiovascular complications were equivalent between groups [39].

At least 9 meta-analyses have been published in the last decade alone [2,49–57]. Results are conflicting; several find no difference in morbidity [2,51,53,56] whereas others suggest an association between MBP and increased anastomotic leak, SSI, or cardiovascular complications [49–52,54,55,57]. Most recently, a 2009 Cochrane review evaluated 14 randomized controlled trials and found no significant difference in wound infection, anastomotic leak rates, noninfectious complications, or mortality [2].

Although these studies have demonstrated no significant differences in outcome based on the use of MBP alone in a general population of colorectal surgery patients, specific subgroups of patients are hypothesized to derive particular benefit or harm from MBP. For example, elective colon operations carry a lower risk of anastomotic leak or septic complications than rectal operations [2]. The differential benefit achieved with MBP is lower for the lower-risk procedure and the threshold for use should be higher. Patients with low rectal anastomoses are particularly prone to develop anastomotic leak. These patients may also be more susceptible to any detrimental effects of MBP on anastomotic healing. Stratification of patients within the Cochrane analysis revealed equivalent leak rates in patients with or without MBP for colon operations but a nonsignificant trend toward increased anastomotic leak in rectal operations performed after MBP [2]. An observational study of more than 100 patients undergoing resection of rectal cancers revealed higher composite morbidity but no difference in leak rates for patients with MBP compared with those who did not undergo bowel preparation [58]. These observations have yet to be confirmed in a dedicated randomized trial.

Similarly, the laparoscopic approach to colectomy carries a lower risk of SSI than the open approach. The value of MBP has been strongly questioned for this procedure; however, data are limited. A recent retrospective review found no difference in anastomotic leak, SSI, or ability to localize a tumor in patients with or without MBP [59]. To date, there is no documented benefit to MBP without oral antibiotics in laparoscopic colon operations.

Elderly patients or those with significant medical comorbidities may be particularly vulnerable to the systemic effects of MBP. Hypovolemia, electrolyte derangement, and acid-base imbalance are all potential consequences of MBP. The latter are most commonly associated with sodium phosphate–based preparations [60,61]. Although outpatient MBP is safe and commonplace, selected patients may benefit from hospital admission for intravenous hydration to mitigate MBP-associated volume depletion [62].

The primary weakness of the data from recent trials and meta-analyses is the omission of oral antibiotics as part of the bowel preparation. Prior to the near universal use of perioperative systemic antibiotics in colorectal surgery, oral antibiotics had an established role in reducing the incidence of wound infections. Even in colorectal surgery patients receiving systemic prophylactic antibiotics, the addition of oral antibiotics reduces the incidence of SSI. A meta-analysis of 14 randomized controlled trials encompassing nearly 2000 patients evaluated oral and systemic antibiotics for colorectal surgery infectious prophylaxis. The combination of oral and systemic antibiotics was clearly shown to be superior to systemic antibiotics alone, with an overall risk difference of 0.56 in favor of the combined regimen (see Fig. 1) [28]. Despite clear evidence in support of oral prophylactic antibiotics, the vast majority of studies compare colorectal surgery without bowel preparation with an MBP regimen that does not include oral antibiotics. Consequently, these trials fail to make their comparison with the established gold standard.

Rare studies have compared colorectal operations without bowel preparation with MBP plus oral antibiotics. Three small studies detected no difference in the incidence of SSI; one suggested an increased risk of antibiotic-associated C diffficile colitis with oral antibiotics [29,30,63]. As these studies are limited by sample size, a large randomized trial is merited.

Current state of practice

Despite the bulk of the literature suggesting that MBP without oral antibiotics confers no advantage, a significant percentage of surgeons continue to employ various types of MBP for colorectal surgery. Survey data from colorectal surgeons in the United States and Canada published in 1997 documented that 100% of the respondents regularly prescribed MBP for elective colorectal operations. More than 85% of these surgeons also used a combination of systemic and oral antibiotics [64]. More recently, a survey of colorectal surgeons in Great Britain and Ireland indicated that nearly half of responding surgeons routinely order MBP for elective left colon surgery [65,66]. Data from 24 hospitals of the MSQC reveal that from 2007 to 2009, 49% of patients received MBP without oral antibiotics prior to elective colectomy. An additional 36% of patients received MBP with oral antibiotics, whereas only 11% of patients did not undergo preoperative bowel preparation [67]. These observations highlight a marked discord between the current practice of bowel preparation and existing evidence.

The Michigan experience

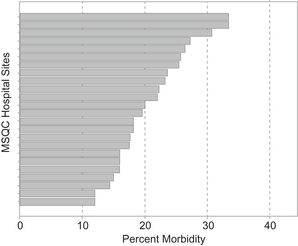

The MSQC—Colectomy Best Practices Project recently embarked on a comprehensive evaluation of the current practices and outcomes of colon operations in the state. Among the 24 sites, overall morbidity rates following elective colectomy range from less than 15% to nearly 35% (Fig. 2). This variation likely stems from the interaction of numerous factors. Differences in preoperative bowel preparation may represent one such factor influencing colectomy outcomes.

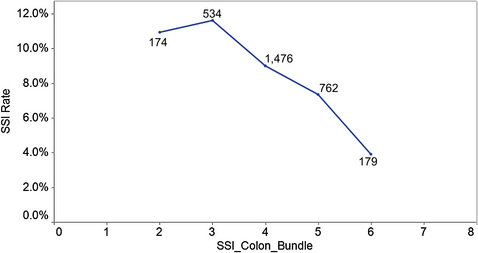

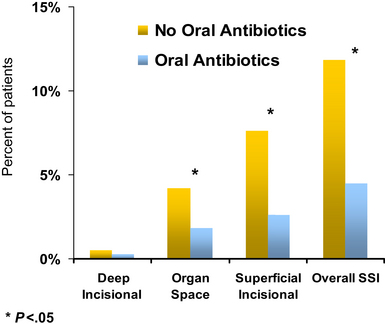

MSQC data from 2007 to 2009 were used to investigate the effect of preoperative bowel preparation with and without oral antibiotics on the incidence of SSI. To control for the multitude of confounding variables, a propensity score was developed and used to derive two study groups differing only in their preoperative bowel preparation regimen. Prophylactic systemic antibiotics were used in nearly all patients, with no statistical difference between the two groups. Patients who received oral antibiotics in addition to MBP had significantly lower rates of organ space and superficial incisional infections than those who did not receive oral antibiotics (Fig. 3) [67]. The cumulative incidence of SSI was less than 5% in the antibiotic group compared with greater than 10% in the no-antibiotic group. Of note, the incidence of C difficile colitis was equivalent in the two groups, while postoperative ileus occurred significantly less frequently in patients who had received preoperative oral antibiotics [67]. This study did not evaluate the efficacy of any given antibiotic regimen, and large randomized trials are still necessary. Nonetheless, these “real-world” data are derived from a diverse group of patients and practice circumstances, and does suggest that oral antibiotics may be an effective means of reducing the incidence of SSI in colorectal surgery patients beyond the structured environment of a clinical trial.

Fig. 3 Oral antibiotics with a bowel preparation: a propensity-matched analysis.

(Data from Englesbe MJ, Brooks L, Kubus J, et al. A statewide assessment of surgical site infection following colectomy: the role of oral antibiotics. Ann Surg 2010;252(3):514–9 [discussion: 519–20]).

The results of this investigation highlighted an opportunity for intervention to improve the outcomes of colectomy in Michigan. The MSQC—Colectomy Best Practices Project used these and other data to develop a list of target practices to reduce SSI after colectomy (Box 3). The implementation of these 7 practice goals has resulted in a decreased incidence of SSI. Patients for whom 3 or fewer targets were met had an SSI rate greater than 10%. This rate decreased with the achievement of additional targets; those patients for whom 6 of 7 targets were reached had an SSI incidence of less than 4% (Fig. 4).

Future directions

Regardless of the bowel preparation regimen chosen, meticulous surgical technique remains paramount, as it has throughout surgical history. In the words of Rowlands, published more than 50 years ago but still relevant, “… the presumed sterility of the bowel lumen should in no way excuse any deviation from the exact and carefully performed technical minutiae which are the foundation of successful bowel surgery” [12].