Anorectal Procedures

Anatomy

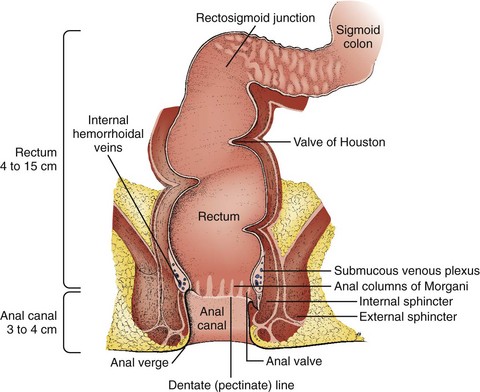

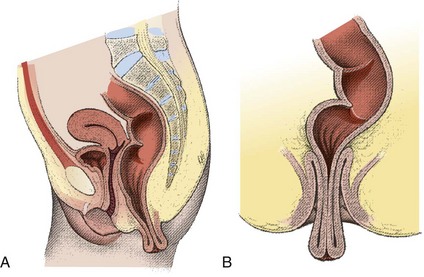

The rectum and anus compose the most distal portion of the gastrointestinal tract. The rectum begins at the level of the third sacral vertebra and extends distally 12 to 15 cm. Blood supply to the anorectum is derived from the superior, middle, and inferior hemorrhoidal arteries. Venous drainage from the rectum and anus returns to both the portal and systemic systems (Fig. 45-1). The dentate or pectinate line marks the transition from the rectum to the anus and contains submucosal glands in anal crypts. Occlusion with subsequent infection of these glands is the etiology of anorectal abscesses. Sensory innervation to the rectum is primarily visceral, whereas the anus is innervated by cutaneous fibers. Therefore, patients are often unaware of rectal pathology because the pain associated with it may be vague or absent. By contrast, anal lesions are usually very painful and well localized.1

DRE

Procedure

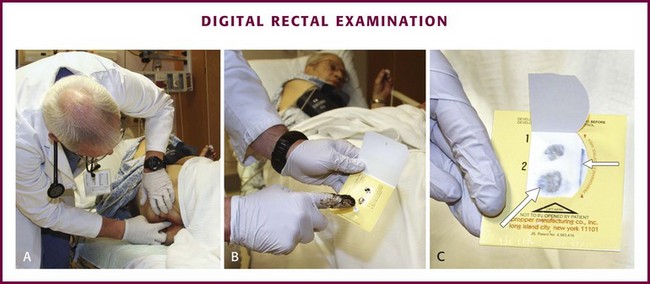

The examiner should place the patient in the lateral decubitus position and wear protective gloves. The examination begins with a preliminary visual inspection of the perianal area for important information regarding patient hygiene, trauma, or sexually transmitted diseases. Next, ask the patient to perform a Valsalva maneuver and note any prolapsing rectal mucosa or hemorrhoids. When the patient relaxes, prolapsed structures may retreat or remain external to the anus. By placing a finger firmly against the anal sphincter, it will relax and allow entry of the examiner’s gloved, lubricated finger (Fig. 45-2A). Once inserted into the anus, make a 360-degree sweep to identify any irregularities in the anorectum and prostate. On withdrawal of the examining finger, examine stool remaining on the glove for the presence of visible or occult blood (see Fig. 45-2B and C).2 Testing for blood in stool is discussed in detail in Chapter 67.

Complications

Although DRE causes some vasovagal depression, it is safe to perform in patients with acute myocardial infarction.3 Although not a firm contraindication in patients whose absolute neutrophil count is dangerously low, some would defer routine DRE, especially avoiding vigorous prostate manipulation, to minimize the likelihood of bacteremia.

Anoscopy

Equipment and Setup

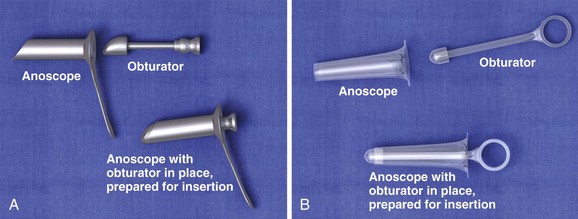

The anoscope is a plastic or stainless steel tube with a removable obturator (Fig. 45-3). It may have an integrated light source or require an external light or head lamp. An appropriate examination table, topical anesthetics, lubricant, gauze, and forceps may also be required.

Positioning

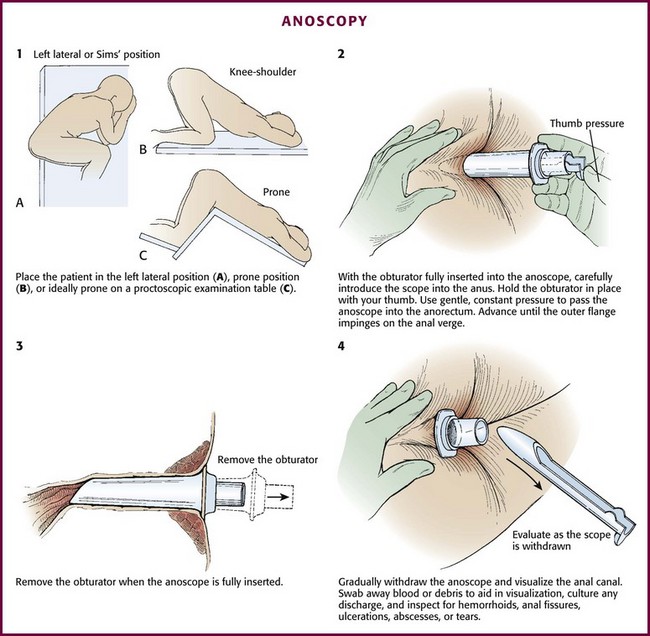

Ideally, place the patient in a prone position on a proctoscopic examination table. The prone or lateral decubitus position with the knees and hips flexed may also be adequate and is sometimes tolerated better. In the lateral decubitus position, place the patient on the left side if the examiner is right-handed (Fig. 45-4, step 1).

Procedure

Although most patients do not require intravenous sedation and analgesia, administer these agents as needed to keep the patient relaxed and comfortable. Before anoscopy, perform a routine DRE to identify sources of bleeding or pain and to locate any palpable masses. After DRE and with the obturator inserted completely into the anoscope, carefully introduce the scope into the anus. Use gentle, constant pressure to overcome resistance from involuntary contraction of the external anal sphincter. Gently advance the anoscope while asking the patient to bear down slightly. Pass the anoscope gently into the anorectum (see Fig. 45-4, step 2). If the obturator falls back during insertion, remove the anoscope completely and replace the obturator to avoid pinching the anal mucosa. Advance the anoscope until the outer flange impinges on the anal verge. Unless the anoscope has an internal light, use an external light source such as a penlight, otoscope, or pelvic examination light.

When the anoscope is fully inserted, remove the obturator (see Fig. 45-4, step 3). While gradually withdrawing the anoscope, visualize the anal canal (see Fig. 45-4, step 4). Swab away blood or debris to aid in visualization, and culture any abnormal discharge that is found. Note whether there is rectal bleeding or an FB beyond the reach of the anoscope. Withdraw the anoscope slowly as the entire circumference of mucosa is inspected for hemorrhoids, anal fissures, ulcerations, abscesses, or tears. Near the last stage of withdrawal, be aware of reflex spasm of the anal sphincter, which may cause the anoscope to be expelled quickly. Use firm counterpressure to prevent such rapid expulsion.

Management of Hemorrhoids

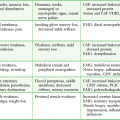

Hemorrhoids are a common affliction and have been described and treated for more than 4000 years. The refined, low-fiber diet of Western nations makes hemorrhoids extremely common in the United States, where 1 in 25 to 30 individuals is afflicted. One million patients annually seek medical attention for this condition.4

Hemorrhoidal tissue is composed of vascular, mucosal, and muscular tissue. Though frequently attributed to varicosities, all three elements are included in hemorrhoids (Fig. 45-5). There are two types of hemorrhoids: internal and external. Internal hemorrhoids originate above the dentate line, are covered with mucosa, and lack sensory innervation. They can be identified by noting that their covering differs in appearance from the surrounding perianal skin. Internal hemorrhoids may prolapse and bleed, which usually produces bright red blood on toilet paper or in the toilet bowel. This bleeding is arterial from presinusoidal arterioles and is mostly associated with brown stool and bleeding only with a bowel movement. Atypical bleeding requires further investigation. Internal hemorrhoids are rarely felt by digital palpation unless they are very large or thrombosed. Internal hemorrhoids are usually painless unless gangrenous, strangulated, extruded, or thrombosed, and then they may be extremely painful. Anal pain in the absence of such pathology suggests a problem other than simple internal hemorrhoids.5

Internal hemorrhoids can be further classified as first through fourth degree. First-degree hemorrhoids do not prolapse but may be identified on anoscopic examination. Second-degree hemorrhoids prolapse on straining but reduce spontaneously. Third-degree hemorrhoids prolapse on straining and can be reduced manually, whereas fourth-degree hemorrhoids prolapse and are irreducible. Fourth-degree hemorrhoids are prone to thrombosis, strangulation, and eventually gangrene (see Fig. 45-5C).

External hemorrhoids originate below the dentate line and are covered with squamous epithelium. This makes them easily recognizable because their covering matches the surrounding skin. A thrombosed external hemorrhoid appears as a bluish mass covered by epidermis. Acute thrombosis occurs suddenly and is generally very painful because external hemorrhoids are innervated by the inferior rectal nerve. Many patients feel a tender mass and are unable to sit comfortably. Significant bleeding is uncommon but may occur with spontaneous rupture. Increased pressure from straining or trauma from constipation or diarrhea may exacerbate external hemorrhoids. Distention and trauma predispose the hemorrhoidal venous plexus to stasis with ensuing clot formation and edema.2,4,6–9

Conservative Treatment

ED management of minor internal hemorrhoids is conservative. Prolapsing internal hemorrhoids will not benefit long-term from conservative intervention and should receive surgical consultation. A useful mnemonic for managing hemorrhoids is WASH: water (increase fluid intake, warm water contacting the hemorrhoid via bath or directed shower), analgesics, stool softeners, and a high-fiber diet.2 Psyllium (e.g., Metamucil) is often prescribed as a dietary supplement to increase fiber. Hemorrhoids that fail to respond to medical management may be treated on an outpatient basis with rubber band ligation, sclerosis, and thermotherapy consisting of an infrared beam, electric current, CO2 laser, or ultrasonic energy. Patients who must push hemorrhoids back in after a bowel movement have symptomatic third-degree internal hemorrhoids and would benefit from elective surgical referral. This condition can easily be demonstrated by having the patient strain before DRE. Nonreducible prolapsed internal hemorrhoids should receive prompt surgical consultation and, frequently, admission to the hospital.6

Without treatment, thrombosed external hemorrhoids and those that have spontaneously ruptured will generally resolve over a period of 1 to 3 weeks. Residual skin tags may persist. During the interim, however, they are quite painful and may bleed. Small ruptured or nonruptured hemorrhoids that are seen acutely with minimal discomfort may be managed conservatively with warm water baths or a directed stream of water, topical corticosteroids (Anusol HC), or Preparation H. These topical agents may promote skin breakdown from the corticosteroid or local anesthetic if used for more than a couple of days. Since the pain is most severe within the first 48 hours, patients evaluated within this time window benefit from excision (not incision and drainage) of the contents of the thrombosed external hemorrhoid and its overlying skin. Patients seen after this time are usually best managed with conservative treatment because the thrombosis begins the reabsorption process and may be liquefied (see Fig. 45-5D).2,4,8,9

Surgical Excision of Thrombosed External Hemorrhoids

Procedure

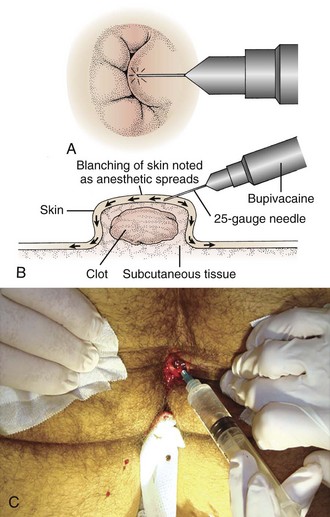

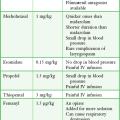

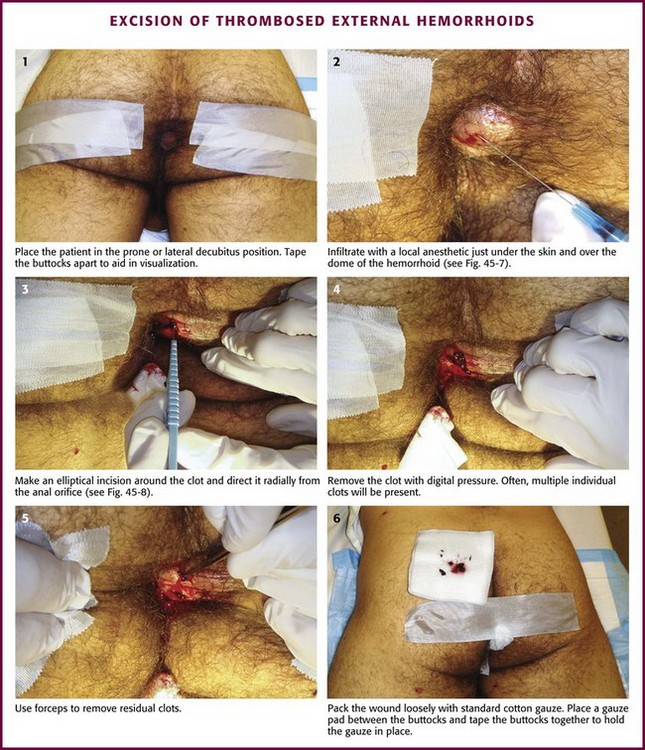

Place the patient in the prone or lateral decubitus position. Tape the buttocks apart to aid in visualization (Fig. 45-6, step 1). An assistant is often needed. Administer parenteral analgesics and sedatives as an adjunct to local anesthesia if necessary. Infiltrate with a local anesthetic (such as 0.5% bupivacaine or buffered 1% lidocaine with epinephrine at 1 : 100,000) just under the skin and over the dome of the hemorrhoid (Fig. 45-7; also see Fig. 45-6, step 2). The overlying skin should blanch, which indicates that anesthesia has been introduced at the appropriate depth. Inject additional anesthetic through the incised tissue into the base of the hemorrhoid rather than through the intact skin if needed (see Fig. 45-7C).

Figure 45-6 Excision of thrombosed external hemorrhoids.

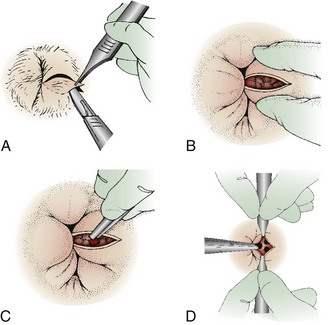

Grasp the skin overlying the thrombosis with forceps. Make an elliptical incision around the clot and direct it radially from the anal orifice (Fig. 45-8; also see Fig. 45-6, step 3). Elevate the edges of the skin with forceps and excise from the edges to expose the underlying thrombosis. Remove the clot with forceps or by applying digital pressure (see Fig. 45-6, steps 4 and 5). Frequently, multiple individual clots will be present. If any skin ulceration is noted over the hemorrhoid, include it in the excised portion. Pack the wound loosely with standard cotton gauze to prevent the skin edges from reapproximating prematurely.

Figure 45-8 Schematic technique as described in Figure 45-6. A, For the unroofing technique, make an elliptical incision to remove a piece of the overlying skin. To prevent skin tags, do not use a simple linear incision. B, Blood clots may extrude spontaneously, but remove the remaining ones with forceps or express them with the fingers (C). D, Frequently, multiple clots are present, and they should all be removed. Ask an assistant to provide exposure with forceps if necessary.

For the trip home, place a gauze pad between the buttocks and tape the buttocks together to hold the gauze in place (see Fig. 45-6, step 6). Advise the patient to avoid prolonged standing or straining for the next few days. Minor bleeding may occur. Hygiene with a directed stream of warm water or sitz baths can be started a few hours after the procedure. The gauze may fall out or can be removed at the first sitz bath. After the packing has been removed, the patient may apply a soothing cream to the area for a couple of days (such as Preparation H, Anusol HC, or witch hazel pads). Instruct the patient to avoid using toilet paper after a bowel movement for a few days but to wash the area with mild soap and water in the shower. Most patients are relatively asymptomatic in 48 hours and do not need a routine wound check unless the pain or bleeding persists. Once the clot has been removed, recurrent thrombosis is unlikely, but these patients are predisposed to future episodes. Long-term therapy should be directed toward avoiding constipation by increasing dietary fiber and fluid intake. Antibiotics are not routinely indicated.2,10

If an invasive procedure would not be well tolerated by the patient, alternative nonoperative treatments include topical nitrates or topical nifedipine. Applied to the thrombosed hemorrhoid, these creams relax the anal sphincter, relieve pain, and promote healing. Systemic absorption is minimal, and the application is usually well tolerated.7

Management of Rectal FBs

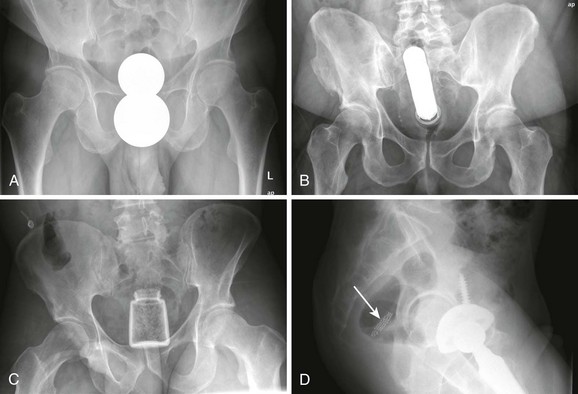

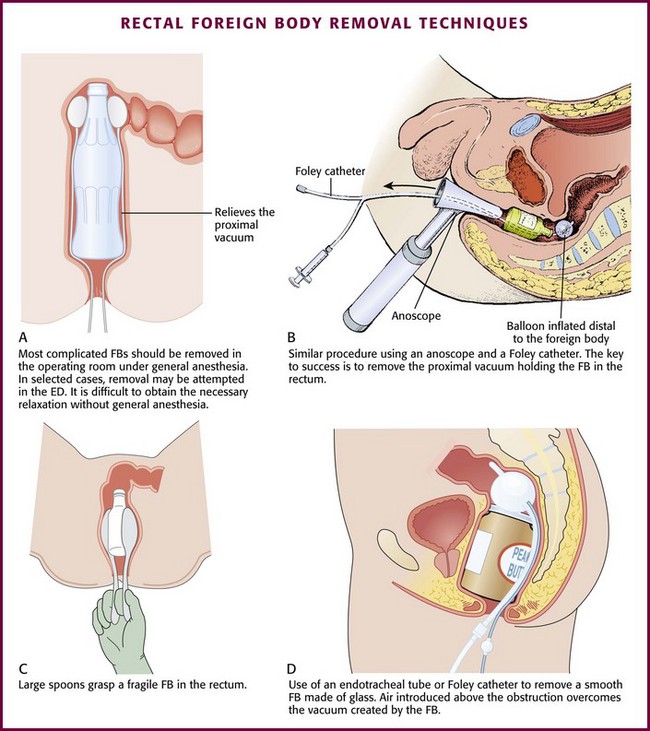

Causes of rectal FBs include autoeroticism (most common), iatrogenic or self-administered placement (thermometer, enema tip), assault, accidental ingestion, and concealment (body packing). The myriad of objects that have been removed include vibrators, sex toy phalluses, aerosol cans, light bulbs, glass bottles, billiard balls, fruits, vegetables, and small animals (Fig. 45-9). Many of these objects can be removed successfully in the ED. By following some simple guidelines, outpatient treatment can be practical and cost-effective.

Diagnosis of a rectal FB is usually made from the history. The physical examination should therefore concentrate on excluding anorectal or intestinal perforation and determining which objects will be accessible in the ED. DRE will identify objects that are low lying or palpable. Such objects are most likely to be removed successfully in the outpatient setting. Plain radiographs can supplement the examination by delineating the shape, position, and number of objects. If an FB with a sharp edge is suspected from the history or radiograph, omit the DRE to prevent injury to the provider.11–13

Indications and Contraindications

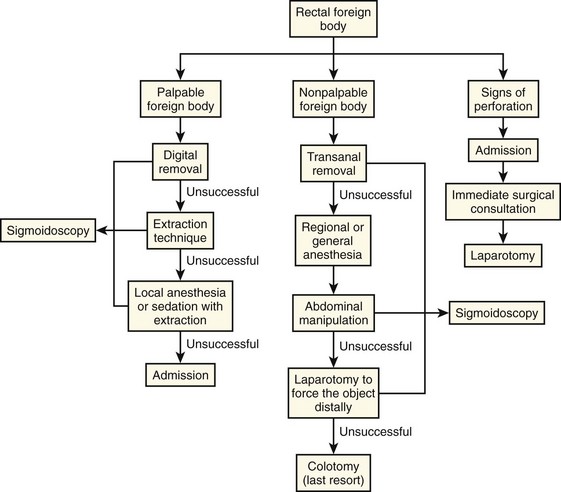

Although some objects may pass spontaneously, delayed removal may lead to obstipation, pain, infection, and perforation. For these reasons, FB removal is indicated according to the algorithm included in this chapter (Fig. 45-10). Rectal FB removal can lead to rectal perforation. Although many FBs can be removed safely in the ED, complicated or prolonged attempts may be better performed under general anesthesia.

Removal of FBs in the ED is contraindicated in patients who have severe abdominal pain or signs of perforation, a nonpalpable FB, or broken glass in the rectum. Other situations precluding ED removal include a rectal FB that is unusually difficult to remove (a set time limit has elapsed or the patient cannot tolerate removal) or when there is insufficient experience or equipment to perform the procedure. Patients who arrive at the ED under these conditions require surgical consultation.11–13

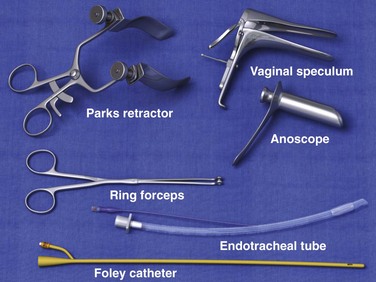

Equipment

The specific equipment required will often depend on the nature of the FB (Fig. 45-11). In general, the clinician will need a speculum with a light source and an instrument to grasp the FB. The speculum can be an anoscope, a rigid sigmoidoscope, a vaginal speculum, or a retractor. Instruments useful for grasping the FB include ring forceps, tenaculum forceps, and obstetric forceps. In some instances, a Foley catheter or endotracheal tube will be helpful. A suction dart, vacuum extractor, and plaster of paris have also been used to aid in FB retrieval. Individual situations may lead to creative use of standard medical equipment, but one must ensure safety before using a device to remove a rectal FB.

Procedure

If DRE reveals that the object has an accessible edge or lip, use an instrument to extract it under direct visualization (Fig. 45-12). First, insert an anoscope, rigid sigmoidoscope, vaginal speculum, or retractor into the anus as described previously in the section “Anoscopy.” If an intact object is visualized clearly, use a blunt instrument to secure it. Apply gentle traction to remove the object, the instrument, and the anoscope or speculum as a single unit. Grasp the object under direct visualization to avoid pinching or tearing the mucosa.

Besides creating a vacuum, glass objects are especially difficult to remove because they can break and cause a tear or perforation in the rectal wall. If forceps are used for retrieval of a glass object, coat the grasping edge with rubber or plastic or pad it with gauze. Plaster of Paris has been used to remove a hollow glass object if the object has an open end facing distally. Insert a hollow tube (e.g., an endotracheal tube or small chest tube) into the open end. Fill the FB with plaster by injecting it through the hollow tube with a large irrigation syringe. Once the plaster cools around the tube, it can be used as a handle to remove the object with gentle traction. Be careful to not leak plaster onto the mucosa. In addition, heat is released as the plaster hardens and may cause the glass to crack or shatter. After removal, perform sigmoidoscopy to evaluate for edema and possible perforation of the mucosa. Patients with normal findings on postextraction examination and no evidence of perforation may be released home safely after a period of observation.11–13

Management of Rectal Prolapse

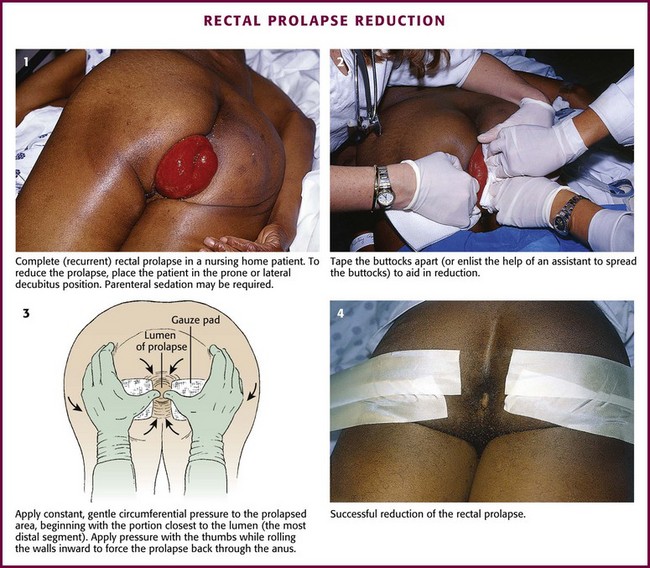

There are three types of prolapse. (1) Complete prolapse, or procidentia, involves all layers of the rectum protruding through the anal orifice (Figs. 45-13 and 45-14). (2) Incomplete, or occult, prolapse describes internal prolapse that does not reach the orifice. This type is difficult to diagnose in the ED and requires no emergency intervention. (3) Mucosal prolapse is limited to protrusion of mucosa through the anal opening.

Figure 45-14 Reduction of rectal prolapse.

Rectal prolapse is most common in children and older adults. Prolapse in children is typically incomplete, or mucosal. It usually affects children younger than 3 years and is often associated with cystic fibrosis, parasitic infection, chronic diarrhea, or malnutrition or occurs as a sequela of chronic neurologic disease. Prolapse is usually self-limited; outpatient management (after manual reduction) includes correcting constipation, avoiding straining, and referring for testing to exclude cystic fibrosis. Rectal prolapse in adults occurs most often in older women and may be recurrent. The etiology is poorly understood, but it is associated with chronic constipation, chronic neurologic conditions, or pudendal neuropathies that weaken the anal sphincter.14–16

Procedure

Reduce a mucosal prolapse by applying gentle, constant pressure on the mass for a few minutes. In children, intravenous sedation may be necessary to allow reduction. Children are often more relaxed if they are allowed to remain in the parent’s lap during the procedure. After reduction, send the child home with a pressure dressing and stool softeners. Counsel the parents on the use of dietary fiber and increased fluid intake to prevent constipation and straining. Refer the child for outpatient follow-up.17

For reduction of a complete prolapse, place the patient in the prone or lateral decubitus position (see Fig. 45-14, step 1). Parenteral sedation may be required if the patient is anxious or has difficulty relaxing the sphincteric muscles. Tape the buttocks apart or have an assistant aid in reduction (see Fig. 45-14, step 2). Apply constant, gentle circumferential pressure to the prolapsed area, beginning with the portion closest to the lumen (the most distal segment). Place the thumbs on either side of the lumen while grasping the exterior walls with the fingers. Apply pressure with the thumbs while rolling the walls inward to force the prolapse back through the anus (see Fig. 45-14, step 3). Care should be taken to avoid poking at the tissue with the fingertips. If substantial tissue edema has developed, application of gauze soaked in sugar water may promote shrinkage and subsequent manual reduction.16

Anal Fissure

An anal fissure is a small laceration or ulcer at the anal verge.5 Anal fissures are the most common cause of anorectal pain. Though appearing trivial on examination, fissures can be extremely painful, even hours after a bowel movement, because of persistent spasm (Fig. 45-15). The condition is quite difficult to eradicate, is debilitating, and can last for months. It is occasionally associated with bright red rectal bleeding. An anal fissure is most commonly found in young adults, men and women equally. In children it can be a sign of child abuse. Anal fissures are usually associated with constipation, a hard or strained stool, or chronic diarrhea, but the exact etiology is unknown. The diagnosis is relatively easy to make, and the fissure is readily seen by spreading the buttocks. The vast majority of anal fissures occur in the posterior midline, 10% to 15% occur in the anterior midline, and less than 1% occur in lateral positions. Fissures occurring in atypical locations should prompt consideration of other diseases. Multiple or recurrent fissures are associated with Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis, syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and malignancy. Conservative therapy with the WASH regimen (see the section on hemorrhoids) may promote gradual healing in 4 to 6 weeks.

References

1. Barleben, A, Mills, S. Anorectal anatomy and physiology. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:1–15.

2. Coates, WC. Anorectum. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby-Elsevier; 2010:1243.

3. Akhtar, AJ, Moran, D, Ganesan, K. Safety and efficacy of digital rectal examination in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1463–1465.

4. Sneider, EB, Maykel, JA. Diagnosis and management of symptomatic hemorrhoids. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:17–32.

5. Schubert, MC, Sridhar, S, Schade, RR, et al. What every gastroenterologist needs to know about common anorectal disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3201.

6. Acheson, AG, Scholefield, JH. Management of haemorrhoids. BMJ. 2008;336:380–383.

7. Kaidar-Person, O, Person, B, Wexner, SD. Hemorrhoidal disease: a comprehensive review. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:102.

8. Lorenzo-Rivero, S. Hemorrhoids: diagnosis and management. Am Surg. 2009;75:636–642.

9. Madoff, RD, Fleshman, JW, for the Clinical Practice Committee, American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of hemorrhoids. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1463–1473.

10. Jongen, J, Bach, S, Stübinger, SH, et al. Excision of thrombosed external hemorrhoid under local anesthesia: a retrospective evaluation of 340 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1226–1231.

11. Goldberg, JE, Steele, SR. Rectal foreign bodies. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:173–184.

12. Lake, JP, Essani, R, Petrone, P, et al. Management of retained colorectal foreign bodies: predictors of operative intervention. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1694–1698.

13. Rodriguez-Hermosa, JI, Codina-Casador, A, Ruiz, B, et al. Management of foreign bodies in the rectum. Colorectal Dis. 2006;9:543–548.

14. Madbouly, KM, Senagore, AJ, Delaney, CP, et al. Clinically based management of rectal prolapse. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:99–103.

15. Karulf, RE, Madoff, RD, Goldberg, SM. Rectal prolapse. Curr Probl Surg. 2001;38:771.

16. Jones, OM. The assessment and management of rectal prolapse, rectal intussusception, rectocoele, and enterocoele in adults. BMJ. 2011;342:c7099.

17. Antao, B, Bradley, V, Roberts, JP, et al. Management of rectal prolapse in children. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;9:1620–1625.