Chapter 515 Anatomic Abnormalities Associated with Hematuria

515.1 Congenital Anomalies

Craig C. Porter and Ellis D. Avner

Gross or microscopic hematuria may be associated with many types of different malformations of the urinary tract. The sudden onset of gross hematuria after minor trauma to the flank is often associated with ureteropelvic junction obstruction or cystic kidneys (see Chapter 531).

515.2 Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease

Diagnosis

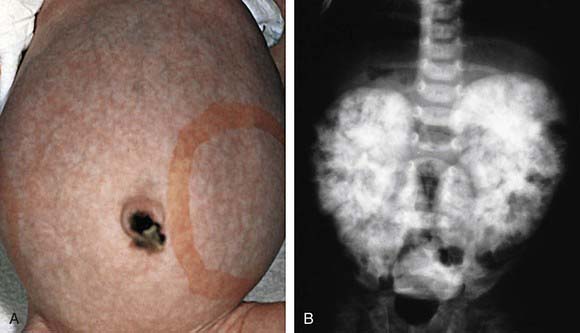

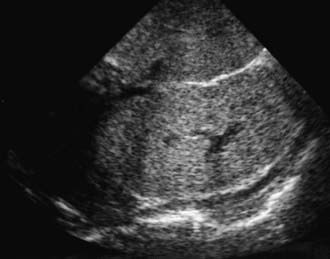

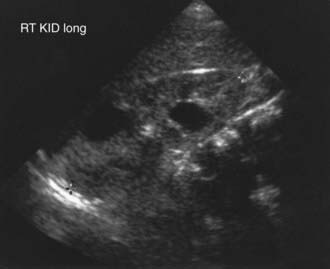

The diagnosis of ARPKD is strongly suggested by bilateral palpable flank masses in an infant with pulmonary hypoplasia, oligohydramnios, and hypertension and the absence of renal cysts by sonography of the parents (Fig. 515-1). Markedly enlarged and uniformly hyperechogenic kidneys with poor corticomedullary differentiation are commonly seen on ultrasonography (Fig. 515-2). The diagnosis is supported by clinical and laboratory signs of hepatic fibrosis, pathologic findings of ductal plate abnormalities seen on liver biopsy, anatomic and pathologic proof of ARPKD in a sibling, or parental consanguinity. The differential diagnosis includes other causes of bilateral renal enlargement and/or cysts, such as multicystic dysplasia, hydronephrosis, Wilms tumor, and bilateral renal vein thrombosis (Table 515-1). Prenatal diagnostic testing using genetic linkage analysis or direct mutation analysis is available in families with ≥1 affected child.

Adeva M, El-Youssef M, Rossetti S, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization defines a broadened spectrum of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD). Medicine. 2006;85:1-21.

Bergmann C, Senderek J, Kupper F, et al. PKHD1 mutations in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD). Hum Mutat. 2004;23:453-463.

Davis ID, Ho M, Hupertz V, et al. Survival of childhood polycystic kidney disease following renal transplantation: the impact of advanced hepatobiliary disease. Pediatr Transplant. 2003;7:364-369.

Dell KM, Avner ED. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. In GeneClinics: Clinical Genetic Information Resource (database online), http://www.geneclinics.org/.

Dell KM, Sweeney WE, Avner ED. Polycystic kidney disease. In: Avner ED, Harmon WE, Niaudet P, et al, editors. Pediatric nephrology. ed 6. Heidelburg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2009:849-888.

Delous M, Baala L, Salomon R, et al. The ciliary gene RPGRIP1l is mutated in cerebello-oculo-renal syndrome (Joubert syndrome type B) and Meckel syndrome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:875-881.

Guay-Woodford LM, Desmond RA. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease: the clinical experience in North America. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1072-1080.

Guay-Woodford M, Parisi MA, Diherty D, et al. MKS3-related celiopathy with features of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease, nephronophthisis, and Joubert syndrome. J Pediatr. 2009;155:386-392.

Plaisier E, Gribouval O, Alamowitch S, et al. COL4A1 mutations and hereditary angiopathy nephropathy, aneurysms, and muscle cramps. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2687-2695.

Rosetti S, Harris PC. Genotype-phenotype correlations in autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1374-1380.

Sweeney WEJr, Avner ED. Molecular and cellular pathophysiology of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD). Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:671-685.

515.3 Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease

Clinical Presentation

The severity of renal disease and the clinical manifestations of ADPKD are highly variable. Although symptomatic ADPKD commonly occurs in the 4th or 5th decade of life, symptoms, including gross or microscopic hematuria, bilateral flank pain, abdominal masses, hypertension, and urinary tract infection, may be seen in children and neonates. Renal ultrasonography usually demonstrates multiple bilateral macrocysts in enlarged kidneys (Fig. 515-3), although normal kidney size and unilateral disease may be seen in the early phase of the disease.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes renal cysts associated with glomerulocystic kidney disease, tuberous sclerosis, and von Hippel-Lindau disease, which may be inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern (see Table 515-1). The neonatal manifestations of ADPKD and ARPKD may be indistinguishable.

Bisceglia M, Galliani CA, Senger C, et al. Renal cystic diseases: a review. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:26-56.

Dell KM, Sweeney WE, Avner ED. Polycystic kidney disease. In: Avner ED, Harmon W, Niaudet P, et al, editors. Pediatric nephrology. ed 6. Heidelburg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2009:849-888.

Fick-Brosnahan GM, Tran ZV, Johnson AM, et al. Progression of autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease in children. Kidney Int. 2001;59:1979-1980.

Grantham JJ. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1477-1484.

Harris PC. 2008 Homer W: Smith Award: insights into the pathogenesis of polycystic kidney disease from gene discovery. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1188-1198.

Hildebrandt F. Genetic kidney diseases. Lancet. 2010;375:1287-1294.

Lau EC, Janson MM, Roesler MR, et al. Birth of a healthy infant following preimplantation PKHD1 haplotyping for autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease using multiple displacement amplification. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27(2):397-407.

Mekahli D, Woolf AS, Bockenhauer D. Similar renal outcomes in children with ADPKD diagnosed by screening or presenting with symptoms. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:2275-2282.

Ong AC. Screening for intracranial aneurysms in ADPKD. BMJ. 2009;339:706-707.

Ong AC, Harris PC. Molecular pathogenesis of ADPKD: the polycystin complex gets complex. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1234-1247.

Takiar V, Caplan MJ. Telling kidneys to cease and decyst. Nat Med. 2010;16(7):751-752.

Torres VE, Harris PC, Pirson Y. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet. 2007;369:1287-1301.

Verdeguer F, Le Corre S, Fischer E, et al. A mitotic transcriptional switch in polycystic kidney disease. Nat Med. 2010;16(1):106-110.

515.4 Trauma

Infants and children are more susceptible to renal injury following blunt or penetrating injury to the back or abdomen owing to their decreased muscle mass “protecting” the kidney. Gross or microscopic hematuria, flank pain, and abdominal rigidity can occur; associated injuries may be present (Chapter 66). In the absence of hemodynamic instability, most renal trauma can be managed nonoperatively. Urethral trauma can result from crush injury, often associated with a fractured pelvis or from direct injury. Such injury is suspected when gross blood appears at the external urethral meatus. Rhabdomyolysis and consequent renal failure is another complication of crush injury that can be ameliorated by vigorous fluid resuscitation.

Dreitlein DA, Suner S, Basler J. Genitourinary trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2001;19:569-590.

Gunal AI, Celiker H, Dogukan A, et al. Early and vigorous fluid resuscitation prevents acute renal failure in the crush victims of catastrophic earthquakes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1862-1867.

Henderson CG, Sedberry-Ross S, Pickard R, et al. Management of high grade renal trauma: 20-year experience at a pediatric level 1 trauma center. J Urol. 2007;178:246-250.