1 An introduction to chronic pelvic pain and associated symptoms

Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to:

1. Highlight the current classifications of chronic pelvic pain syndromes (CPPS) and define the terms used within this book;

2. Summarize the layout of the book and the topics covered in individual chapters;

3. Inform the reader of how little is known about the aetiology of CPP;

4. Remind the reader that as most treatment options are currently empirical, there is a great requirement for careful clinical reasoning when approaching the management of a patient with CPP.

Definitions of chronic pelvic pain syndromes

It is suggested that approximately 15–20% of women, aged 18–50 years, have experienced CPP lasting for more than one year (Howard 2000) and a prevalence of 8% CPPS is estimated in the US male population (Anderson 2008). However, overall prevalence rates of CPP are likely to be underdiagnosed, in part due to the lack of agreed-upon definitions and subsequent difficulty in categorizing CPP (Clemens et al. 2005, Fall et al. 2010).

Pain is defined as ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience, associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or is described in terms of such damage’ (Merskey & Bogduk 2002) and central neurologic mechanisms will play a major role in the aetiology and pathophysiology of CPP. To emphasize that pathology would not always be found where the pain was perceived and that there would most likely be overlapping mechanisms and symptoms between different CPP conditions, the updated European Association of Urology (EAU) classification of CPP (Fall et al. 2010) reflected a shift from definitions based on assumptions of pathophysiological causes, to one based on recommendations of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) (Merskey & Bogduk 2002) and the International Continence Society (ICS) (Abrams et al. 2003).

Therefore in most examples of CPP-related syndromes, and those listed in Box 1.1, marked with an asterisk, it is important to note that they are not the result of infection or pathology, and are characterized by persistent, recurrent or episodic pain (Abrams et al. 2002, Fall et al. 2010).

Box 1.1 Common chronic pelvic pain syndromes

• Anorectal pain syndrome: * Persistent or recurrent, episodic rectal pain with associated rectal trigger points/tenderness related to symptoms of bowel dysfunction.

• Bladder pain syndrome: * Suprapubic pain related to bladder filling, accompanied by other symptoms such as increased daytime and night-time frequency, with no proven urinary infection or other obvious pathology. The European Society for the Study of IC/PBS (ESSIC) publication places greater emphasis on the pain being perceived in the bladder (Van de Merwe et al. 2008).

• Clitoral pain syndrome: * Pain localized by point-pressure mapping to the clitoris.

• Endometriosis-associated pain syndrome: Chronic or recurrent pelvic pain where endometriosis is present but does not fully explain all the symptoms (Fall et al. 2010).

• Epididymal pain syndrome: * Persistent or recurrent episodic pain localized to the epididymis on examination. Associated with symptoms suggestive of urinary tract or sexual dysfunction. No proven epididymo-orchitis or other obvious pathology (a more specific definition than scrotal pain syndrome (Fall et al. 2010).

• Interstitial cystitis (IC): Within the EUA guidelines, IC is included within painful bladder pain syndromes. It is frequently diagnosed by exclusion. Positive factors leading to a diagnosis of IC include: bladder pain (suprapubic, pelvic, urethral, vaginal or perineal) on bladder filling, relieved by emptying, and characterized by urgency, and (commonly) the finding of submucosal haemorrhage (glomerulations) on endoscopy. IC is immediately ruled out in the presence of a variety of pathological conditions, including bacterial infection (Hanno et al. 1999, Peeker & Fall 2002).

• Pelvic floor muscle pain: * Persistent or recurrent, episodic, pelvic floor pain with associated trigger points, which is either related to the micturition cycle or associated with symptoms suggestive of urinary tract, bowel or sexual dysfunction.

• Pelvic pain syndrome: Persistent or recurrent episodic pelvic pain associated with symptoms suggesting lower urinary tract, sexual, bowel or gynaecological dysfunction. No proven infection or other obvious pathology (Abrams et al. 2002).

• Penile pain syndrome: * Pain within the penis that is not primarily in the urethra. Absence of proven infection or other obvious pathology (Fall et al. 2010).

• Perineal pain syndrome: * Persistent or recurrent, episodic, perineal pain either related to the micturition cycle or associated with symptoms suggestive of urinary tract or sexual dysfunction.

• Post-vasectomy pain syndrome: Scrotal pain syndrome that follows vasectomy.

• Prostate pain syndrome: Persistent or recurrent episodic prostate pain, associated with symptoms suggestive of urinary tract and/or sexual dysfunction (Fall et al. 2010). This definition is adapted from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus definition and classification of prostatitis (Krieger et al. 1999) and includes conditions described as ‘chronic pelvic pain syndrome’. Using the NIH classification system, prostate pain syndrome may be subdivided into type A (inflammatory) and type B (non-inflammatory).

• Pudendal pain syndrome: A neuropathic-type pain arising in the distribution of the pudendal nerve with symptoms and signs of rectal, urinary tract or sexual dysfunction. (This is not the same as the well-defined pudendal neuralgia.)

• Scrotal pain syndrome: * Persistent or recurrent episodic scrotal pain associated with symptoms suggestive of urinary tract or sexual dysfunction. No proven epididymo-orchitis or other obvious pathology (Abrams et al. 2003). This may be unilateral or bilateral, and is a common complaint in urology clinics.

• Testicular pain syndrome: * Persistent or recurrent episodic pain localized to the testis on examination, which is associated with symptoms suggestive of urinary tract or sexual dysfunction. No proven epididymo-orchitis or other obvious pathology. This is a more specific definition than scrotal pain syndrome (Abrams et al. 2002).

• Urethral pain syndrome: * Recurrent episodic urethral pain, usually on voiding, with daytime frequency and nocturia (Abrams et al. 2003).

• Vaginal pain syndrome: * Persistent or recurrent episodic vaginal pain associated with symptoms suggestive of urinary tract or sexual dysfunction.

• Vestibular pain syndrome (formerly vulval vestibulitis): Refers to pain that can be localized by point-pressure mapping to one or more portions of the vulval vestibule.

• Vulvar pain syndrome: Subdivided into generalized and localized syndromes:

This shift in definition is important to avoid incorrect diagnostic terms and descriptors as erroneous diagnostic terms are frequently associated with inappropriate investigations, treatments, patient expectations and potentially a worse prognostic outlook (Fall et al. 2010).

Terms that imply infection or inflammation should be avoided unless these are known to exist. For example, treatment choices for chronic prostate pain are often based on anecdotal evidence, with most patients requiring multimodal treatment aimed at their symptoms and comorbidities. Only between 5% and 7% of all chronic prostatitis complaints yield evidence of bacterial involvement (Anderson 2008), and the concept of chronic pain deriving from inflammatory conditions of the prostate is questionable (Nickel et al. 2003). Similarly, a diagnosis of interstitial cystitis (IC) suggests that the bladder interstitium is inflamed, despite evidence to the contrary in most cases.

Additional confusion results from the presence of lesions necessary for diagnosis of type 1 IC in healthy women following bladder distension (Waxman et al. 1998). It appears that urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes (UCPPS) frequently evolve in otherwise healthy men and women, with no obvious pathogenic aetiological evidence, or objective biological markers of disease (Anderson 2008). EAU guidelines have therefore moved away from using ‘prostatitis’ and ‘interstitial cystitis’ in the absence of proven inflammation or infection.

Baranowski (2009) suggests that where pain is a major feature of a condition it is appropriate to name the region/area/organ where the individual perceives the pain – for example painful bladder syndrome. Such a label does not imply any mechanism, merely a location, while inclusion of the word syndrome takes account of any ‘emotional, cognitive, behavioural and sexual [associations or] consequences of the chronic pain’. The mechanisms involved may be associated with local, peripheral or central neural behaviour, and may involve psychological and/or functional influences, reaction and effects. None of these aspects are however implied by the name ‘bladder pain syndrome’, although all are subsumed into its potential aetiology and presentation.

In general management of CPP Fall et al. (2010) suggest a sequence in which initial consideration is given to the organ system in which the symptoms appear to be primarily perceived. Where a recognized pathological process exists (infection, neuropathy, inflammation, etc.), this should be diagnosed and treated according to national or international guidelines. However, when such treatment is ineffectual in relation to the pain, additional tests, such as cystoscopy or ultrasound, should be performed. If such tests reveal pathology this should be treated appropriately; however, if such treatment has no effect, or no pathology is found by additional tests, investigation via a multidisciplinary approach is called for (see Chapters 6, 7 and 8).

Chronic pain

As practitioners working with people in chronic pain, we therefore need to remind ourselves that the structural–pathology model for explaining chronic pain is outdated, particularly as the relationship between pain and the state of the tissues becomes weaker as pain persists (Moseley 2007). A summary of the sensitization processes involved in CPP (Fall et al. 2010) suggests that persistent pain is associated with changes in the central nervous system (CNS) that may maintain the perception of pain in the absence of acute injury. The CNS changes may also magnify non-painful stimuli that are subsequently perceived as painful (allodynia), with painful stimuli being perceived as more painful than expected (hyperalgesia). For example, pelvic floor muscles may become hyperalgesic, and may contain multiple trigger points. This process may lead to organs becoming sensitive, for example the uterus with dyspareunia and dysmenorrhoea, or the bowel with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Berger et al. (2007) have indicated that men with chronic prostatitis have more generalized pain sensitivity, and current thinking suggests that if there has been an inciting event, such as infection or trauma, it results in neurogenic inflammation in peripheral tissues and the CNS (Pontari & Ruggieri 2008). Later chapters – particularly Chapter 3 – will consider both the local and the general influences on, as well as the nature of, pain, occurring in pelvic structures.

The following chapters include pain-oriented discussion:

• Chapter 3: Chronic pain mechanisms;

• Chapter 8: Multispeciality and multidisciplinary practice; Chronic pelvic pain and nutrition;

• Chapter 10: Biofeedback in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic essential pelvic pain disorders;

• Chapter 11.1: Soft tissue manipulation approaches to chronic pelvic pain (external);

• Chapter 11.2: Connective tissue and the pudendal nerve in chronic pelvic pain

• Chapter 13: Practical anatomy, examination, palpation and manual therapy release techniques for the pelvic floor;

• Chapter 15: Intramuscular manual therapy: Dry needling.

Pelvic girdle pain and CPP: To separate or combine?

A reading of this definition of PGP can be seen to specifically exclude the pelvic organs and soft tissues, while the definition of CPP as provided in Table 1 in Fall et al. (2004, 2010) appears to allow for the consideration of all pelvic structures, including the pelvic framework.

So whilst simultaneously reminding the reader of ‘no brain, no pain’ (Butler & Moseley 2003), one of the aims of this book is to avoid what can be considered to be an artificial separation of the functions and structures of the entire pelvic region.

Connecting PGP with CPP

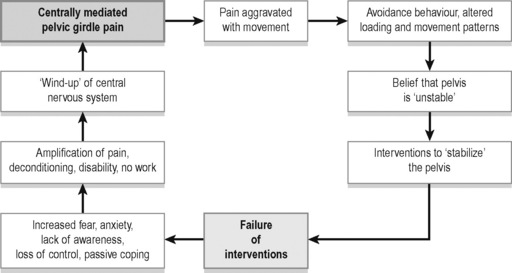

O’Sullivan & Beales (2007) suggest that the motor control system can become dysfunctional in a variety of ways, and that such changes may represent a response to a pain disorder (i.e. it may be adaptive), or might promote abnormal tissue strain, and therefore be seen to be ‘mal-adaptive’, or provocative of subsequent pain disorders (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 • The vicious cycle of pain for centrally mediated pelvic girdle pain.

Adapted from O’Sullivan P, Beales D (2007) Diagnosis and classification of pelvic girdle pain disorders, Part 2: Illustration of the utility of a classification system via case studies. Manual Therapy 12 with permission

Additionally the pelvic floor itself may be involved in such adaptations – with the possibility of CPP symptoms emerging (O’Sullivan 2005).

Consideration of the biomechanical aspects of CPP and PGP will be found in:

• Chapter 2: The anatomy of pelvic pain;

• Chapter 9: Breathing and chronic pelvic pain: Connections and rehabilitation features;

• Chapter 11.1: Soft tissue manipulation approaches to chronic pelvic pain (external);

• Chapter 11.2: Connective tissue and the pudendal nerve in chronic pelvic pain;

• Chapter 12: Evaluation and pelvic floor management of urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes;

• Chapter 14: Patients with pelvic girdle pain – An osteopathic perspective.

Aetiological features of CPP

Some identifiable aetiological features commonly associated with CPP often involve one or more of the following factors summarized in Box 1.2.

Box 1.2 Aetiological aspects of CPP

• Abuse (see also Trauma, below): Studies designed to evaluate factors predisposing to CPP and recurrent pelvic pain have demonstrated that several psychological factors, including sexual abuse and alcohol and drug abuse, are strongly associated with CPP and with dysmenorrhoea and dyspareunia (Raphael et al. 2001, Latthe et al. 2006).

• Adhesions: Found in 25% of women with CPP, but a direct causal link with associated pain has not been established (Stones & Mountfield 2000).

• Autoimmune conditions (Tomaskovic et al. 2009, Twiss et al. 2009).

• Biomechanical: Levator ani spasm, piriformis syndrome, and other musculoskeletal conditions have been associated with CPP in many instances (Tu et al. 2006) as have trigger points (Carter 2000, Fitzgerald et al. 2009).

• Circulatory: In one study presence of pelvic varicose veins was noted in 30 of 100 women with CPP of undetermined origin (Gargiulo et al. 2003).

• Gender: Females predominate – with studies showing prevalence ranging from 10 per 100 000 to 60 per 100 000 (Bade & Rijcken 1995, Curhan & Speizer 1999), with significantly higher rates in young women (Parsons & Tatsis 2004).

• Hormonal: Dysmenorrhoea and endometriosis may benefit from hormonal therapy (Howard 2000).

• Infection: Previous or concealed – for example involving the periurethral glands or ducts (see note at start of Box 1.1) (Parsons et al. 2001).

• Inflammation (though not always) (Bedaiwy et al. 2006, Twiss et al. 2009).

• Neurological: A recent study suggested that ‘denervation that is caused by injuries to uterine neuromuscular bundles and myofascial supports is succeeded by re-innervation that may provide an explanation for some forms of chronic pain that is associated with endometriosis’ (Atwal et al. 2005). Pontari & Ruggieri (2008) note that ‘Pelvic pain also correlates with the neurotrophin nerve growth factor implicated in neurogenic inflammation and central sensitization’.

• Psychiatric: The rate of major depression among patients with CPP has been found to be in the order of 30–45% (Gomel 2006, Latthe et al. 2006). In a different study depression was present in 86% of women with both endometriosis and CPP, and only in 38% of the women with endometriosis and no CPP (Lorencatto et al. 2006).

• Trauma (see also Abuse, above): 40–50% of women with chronic pelvic pain have a history of physical or sexual abuse, which could explain psychological or neurological components of pain. Research also suggests that trauma may heighten physical sensitivity to pain (Howard 2000).

However, in most cases the aetiology of CPP remains unknown, with no identifiable organic cause (Gomel 2007). Susceptibility to ill-health – in general – and to particular conditions such as those involving CPP, usually has multiple causes, since all manner of features, factors and events can compromise the individual’s ability to self-regulate.

Beyond single causes

A linking of genetic susceptibility with some instances of CPP (discussed further below) suggests an interaction between lifestyle and environmental factors, and the unique genetic make-up of the individual (Dimitrakov & Guthrie 2009).

As to what such environmental factors might be, Tak & Rosmalan (2010) discuss the role of the body’s ‘stress responsive systems’ in what have been termed functional somatic syndromes, for example IBS (Lane et al. 2009), as involving a ‘multifactorial interplay between psychological, biological, and social factors’. They conclude that stress responsive system dysfunction may be involved in the aetiology of such conditions. There is therefore a need to move beyond a search for single causes of most conditions involving CPP, since, like many other complex and difficult-to-treat conditions, CPP commonly has multifactorial aetiological features – possibly interacting with predispositions and altered stress-coping functions.

Beales (2004) has described a scenario that highlights multiple contributory factors to functional somatic syndromes:

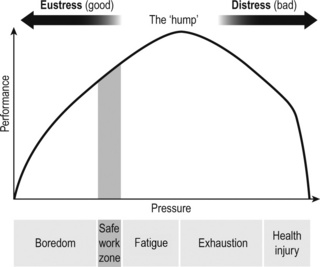

Too much sustained, unhealthy, down slope arousal (see Figure 1.2) leads to the loss of internal balance, and results in reduced performance and a mind–body system in overdrive. In this state, the metabolism is struggling and cholesterol, blood sugar and blood pressure are often raised, resulting in ill-health. The more aroused we become, the more sleep, which would be to some degree restorative, decreases. Signals of mind–body protest multiply. For instance, sufferers from irritable bowel syndrome may also commonly experience back pain, fatigue and loss of libido. Negative emotions, such as frustration and despair, can trigger exhaustion, which in turn can trigger breathing pattern disorders, as a consequence of the perceived threat to survival eliciting fight, flight or freeze reactions.

Recent research has indicated that there may be a genetic tendency operating in some people with CPP. Dimitrakov & Guthrie (2009) note that:

Interesting as such considerations might be to researchers, a finding of a genetic link to CPP is unlikely to offer solutions to a patient’s current CPP problem. Yet phenotypes result from the expression of an organism’s genes, as well as the influence of environmental factors and the interactions between the two. Understanding the classifications, and possible aetiological features of a particular manifestation of CPP, should help determine a successful therapeutic plan. For example, Baranowski (2009) explains:

Making sense of the multiple clinical features in any individual with CPP and arriving at a therapeutic plan therefore calls for careful evaluation of the evidence. In Chapter 7 the question of the role of clinical reasoning, in the differential diagnosis and management of chronic pelvic pain, is explored in depth. How individuals and organizations set about combining clinical assessment and therapeutic expertise, experience and evidence is clearly of major importance when handling complex problems such as CPP and its multiple associated symptoms.

Treatment aimed at pathology is only part of the answer

There would be little need for this book were current treatment strategies that focus on CPP proving successful. Anderson (2006) notes that traditional medical therapy to treat CPP conditions has failed, ‘whether involving antibiotics, anti-androgens, anti-inflammatories, α-blockers, thermal or surgical therapies, and virtually all phytoceutical approaches’. Shoskes & Katz (2005) concur – demonstrating that a series of monotherapies, used to treat hundreds of men with prostatitis, resulted in only 19% reporting any relief of symptoms. However a randomized clinical trial designed to assess the feasibility of conducting a full-scale trial of physical therapy methods in 48 patients with urological CPPS has shown promise (Fitzgerald et al. 2009). It compared two methods of manual therapy: myofascial physical therapy and global therapeutic massage. The global response rate of 57% in the myofascial physical therapy group was significantly higher than the rate of 21% in the global therapeutic massage treatment group (P = 0.03) suggesting a beneficial effect of myofascial physical therapy.

However, Pontari & Ruggieri (2008) note that the symptoms of CP/CPPS appear to result from interplay between psychological factors and dysfunction in the immune, neurological and endocrine systems. It therefore seems unarguable that therapeutic approaches should adopt strategies that take account of these multiple interacting factors. And this is precisely the approach that this book takes.

For example psychological issues are considered in:

• Chapter 4: Psychophysiology and pelvic pain;

• Chapter 6: Musculoskeletal causes and the contribution of sport to the evolution of chronic lumbopelvic pain;

• Chapter 8: Multispeciality and multidisciplinary practice;

• Chapter 9: Breathing and chronic pelvic pain: Connections and rehabilitation features;

• Chapter 10: Biofeedback in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic essential pelvic pain disorders;

• Chapter 12: Evaluation and pelvic floor management of urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes.

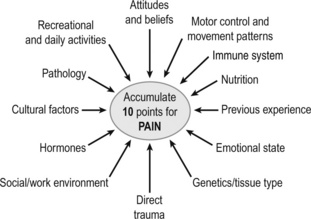

So how can the therapist explain CPP to their patient and what makes one patient more susceptible to chronic pain than another? As outlined previously, the aetiology is unclear but it is apparent that multiple factors somehow contribute to the pain experience. With this belief system in mind, a ‘10 points to pain’ model is one concept that a number of patients and clinicians have found useful (Jones 2003) (Figure 1.3). It is an easy way to demonstrate that pain can develop through many different reasons and works on the premise that pain is rarely the result of one single incident, but normally stems from a range of different issues or a whole lifestyle that contribute to the 10 points and painful state.

Figure 1.3 • Accumulate 10 points for pain; some factors that appear to influence the accumulation of a pain experience.

Reproduced, with permission, from Jones (2003)

In this way, the patient and therapist can move away from the solely structural pathological model, to one that considers, for example, the brain in pain, their beliefs about their pain, nutritional issues, in addition to any pathology or motor control issues. For example, there is evidence that understanding pain reduces the threat of it, altering patients’ attitudes and beliefs, increasing pain thresholds and, when combined with physiotherapy, reduces pain and disability (Moseley 2007). It is therefore important to understand what the patient believes the pain means and help explain modern pain biology, thereby reducing the patient’s attitude and beliefs points. For example the patient may have a belief that:

• Pain only occurs when they have damaged or injured themselves;

• Chronic pain means that an injury has not healed properly;

• Worse injuries always result in worse pain;

• All pain must go before they can resume work or their hobbies;

• Something is terribly wrong with their back/pelvis/pelvic organs, it is just that no-one has performed the right tests;

• They are unable to help themselves overcome their pain, and think that someone else has to fix it.

Abrams P., Cardozo L., Fall M., et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Subcommittee of the International Continence Society. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.. 2002;187:116-126.

Abrams P., Cardozo L., Fall M., et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Subcommittee of the International Continence Society. Urology. 2003;61;(1):37-49. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12559262.

ACOG. Practice Bulletin No. 51. Chronic pelvic pain. Obstet. Gynecol.. 2004;103(3):589-605.

Anderson R. Traditional therapy for chronic pelvic pain does not work: What do we do now? Nat. Clin. Pract. Urol.. 2006;3(3):145-156.

Anderson R. The role of pelvic floor therapies in chronic pelvic pain syndromes. Current Prostate Reports. 2008:139-144. 6

Atwal G., du Plessis D., Armstrong G., Slade R., Quinn M. Uterine innervation after hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain with, and without endometriosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.. 2005;193:1650-1655.

Bade J.J., Rijcken B. Interstitial cystitis in the Netherlands: prevalence, diagnostic criteria and therapeutic preferences. J. Urol.. 1995;154:2035-2037.

Baranowski A. Chronic pelvic pain. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol.. 2009;23:593-610.

Beales D. I’ve got this pain …. Human Givens Journal. 2004;11(4):16-18.

Bedaiwy M.A., Falcone T., Goldberg J.M., et al. Peritoneal fluid leptin is associated with chronic pelvic pain but not infertility in endometriosis patients. Hum. Reprod.. 2006;21:788-791.

Berger R., Ciol M., Rothman I., Turner J. Pelvic tenderness is not limited to the prostate in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) type IIIA and IIIB: comparison of men with and without CP/CPPS. BMC Urol.. 2007;7:17.

Butler D., Moseley G.L. Explain pain. Adelaide: NOI Group Publishing; 2003.

Carter J. Abdominal wall and pelvic myofascial trigger points. In: Howard F.M., editor. Pelvic pain. Diagnosis and management. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:314-358.

Clemens J.Q., Meenan R.T., Richard T., et al. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis symptoms in a managed care population. J. Urol.. 2005;174(2):576-580.

Curhan G.C., Speizer F.E. Epidemiology of interstitial cystitis: a population based study. J. Urol.. 1999;161:549-552.

Dimitrakov J., Guthrie D. Genetics and phenotyping of urological chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J. Urol.. 2009;181(4):1550-1557.

Fall M., Baranowski A., Fowler C., et al. EAU guidelines on chronic pelvic pain. Eur. Urol.. 2004;46(6):681-689.

Fall M., Baranowski A., Elneil S., et al. EAU guidelines on chronic pelvic pain. European Association of Urology. 2008. web site http://www.uroweb.org/fileadmin/tx_eauguidelines/2009/Full/CPP.pdf

Fall M., Baranowski A., Elneil S., et al. EAU guidelines on chronic pelvic pain. Eur. Urol.. 2010;57(1):35-48.

Fitzgerald M.P., Anderson R., Potts J., et al. Randomized multicenter feasibility trial of myofascial physical therapy for the treatment of urological chronic pelvic pain syndromes. J. Urol.. 2009;182(2):570-580.

Gargiulo T., Mais V., Brokaj L., et al. Bilateral laparoscopic transperitoneal ligation of ovarian veins for treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome. J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc.. 2003;10:501-504.

Gomel V. Foreword. In: Li T.C., Ledger W.L., editors. Chronic Pelvic Pain. London, UK: Taylor and Francis, 2006.

Gomel V. Chronic pelvic pain: A challenge. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol.. 2007;14:521-526.

Hanno P., Landis J., Matthews-Cook Y. The diagnosis of interstitial cystitis revisited: lessons learned from the National Institutes of Health Interstitial Cystitis Database study. J. Urol.. 1999;161(2):553-557.

Howard F. The role of laparoscopy as a diagnostic tool in chronic pelvic pain. Baillieres Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol.. 2000;14:467-494.

Jones R.C. The Back Detective: Course notes and book in preparation. 2003–2010.

Krieger J., Nyberg L., Nickel J. NIH consensus definition and classification of prostatitis. JAMA. 1999;282:236-237.

Lane R., Waldstein S., Critchley H., et al. The rebirth of neuroscience in psychosomatic medicine, Part II: clinical applications and implications for research. Psychosom. Med.. 2009;71:135-151.

Latthe P., Mignini L., Gray R., et al. Factors predisposing women to chronic pelvic pain: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;332:749-755.

Lorencatto C., Petta C., Navarro M., et al. Depression in women with endometriosis with and without pelvic pain. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand.. 2006;85:88-92.

Merskey H., Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain. Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. IASP Press; 2002.

Moseley G.L. Reconceptualising pain according to modern pain science. Phys. Ther. Rev.. 2007;12(3):169-178.

Nickel J., Alexander R., Schaeffer A., et al. Leukocytes and bacteria in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome compared to asymptomatic controls. J. Urol.. 2003;170(3):818-822.

O’Sullivan P.B. Clinical instability of the lumbar spine: its pathological basis, diagnosis and conservative management. In: Jull G.A., Boyling J.D., editors. Grieve’s modern manual therapy. third ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2005:311-331. [Chapter 22]

O’Sullivan P., Beales D. Diagnosis and classification of pelvic girdle pain disorders, Part 2: Illustration of the utility of a classification system via case studies. Man. Ther.. 2007;12:e1-e12.

Parsons C., Zupkas P., Parsons J. Intravesical potassium sensitivity in patients with interstitial cystitis and urethral syndrome. Urology. 2001;57:428-432.

Parsons C.L., Tatsis V. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis in young women. Urology. 2004;64:866-870.

Peeker R., Fall M. Toward a precise definition of interstitial cystitis: further evidence of differences in classic and nonulcer disease. J. Urol.. 2002;167(6):2470-2472.

Pontari M., Ruggieri M. Mechanisms in prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2008;179:S61-S67.

Raphael K., Widom C., Lange G. Childhood victimization and pain in adulthood: a prospective investigation. Pain. 2001;92:283-293.

Shoskes D., Katz E. Multimodal therapy for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Curr. Urol. Rep.. 2005;6(4):296-299.

Stones R.W., Mountfield J. Interventions for treating chronic pelvic pain in women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (4):2000. CD000387

Tak L., Rosmalan J. Dysfunction of stress responsive systems as a risk factor for functional somatic syndromes. J. Psychosom. Res.. 2010;68(5):461-468.

Tomaskovic I., Ruzica B., Trnskia D., et al. Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in males may be an autoimmune disease, potentially responsive to corticosteroid therapy. Med. Hypotheses. 2009;72(3):261-262.

Tu F.F., As-Sanie S., Steege J.F. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in a chronic pain clinic. J. Reprod. Med.. 2006;51:185-189.

Twiss C., Kilpatrick L., Triaca V., et al. Evidence for central hyperexitability in patients with interstitial cystitis. J. Urol.. 2009;177:49.

van der Merwe J.P., Nordling J., Bouchelouche P., et al. Diagnostic criteria, classification, and nomenclature for painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis: an ESSIC proposal. Eur. Urol.. 2008;53:60-67.

Vleeming A., Albert H., Östgaard H., et al. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. Eur. Spine J.. 2008;17(6):794-819.

Waxman J.A., Sulak P.J., Kuehl T.J. Cystoscopic findings consistent with interstitial cystitis in normal women undergoing tubal ligation. J. Urol.. 1998;160:1663-1667.