Alternative Regional Analgesic Techniques for Labor and Vaginal Delivery

David H. Chestnut MD

Neuraxial analgesic techniques are the most flexible analgesic techniques available for obstetric patients. The anesthesia provider may use an epidural or a spinal technique to provide effective analgesia during the first and/or second stage of labor. Subsequently, the epidural or spinal technique may be used to achieve anesthesia for either vaginal or cesarean delivery. Unfortunately, some maternal conditions (e.g., coagulopathy, hemorrhage) contraindicate the administration of neuraxial analgesia. Many parturients do not have access to neuraxial analgesia, and others do not want it. The purpose of this chapter is to discuss alternative regional analgesic techniques for labor and vaginal delivery.

Paracervical Block

During the first stage of labor, pain results primarily from dilation of the cervix and distention of the lower uterine segment and upper vagina. Pain impulses are transmitted from the upper vagina, cervix, and lower uterine segment by visceral afferent nerve fibers that join the sympathetic chain at L2 to L3 and enter the spinal cord at T10 to L1. Some obstetricians perform paracervical block to provide analgesia during the first stage of labor. The goal is to block transmission through the paracervical ganglion—also known as Frankenhäuser’s ganglion—which lies immediately lateral and posterior to the cervicouterine junction.

Paracervical block does not adversely affect the progress of labor. Further, it provides analgesia without the annoying sensory and motor blockade that may result from neuraxial analgesia. The paracervical technique does not block somatic sensory fibers from the lower vagina, vulva, and perineum. Thus, it does not relieve the pain caused by distention of these structures during the late first stage and second stage of labor. Contemporary experience suggests that paracervical block results in satisfactory analgesia during the first stage of labor in 50% to 75% of parturients. One study noted that paracervical block provided better analgesia in nulliparous women than in parous women, probably because paracervical block does not provide effective analgesia for the sudden and rapid descent of the presenting part that often occurs in parous women.1

In 1981, approximately 5% of laboring women in the United States received paracervical block,2 and 2% to 3% of parturients in the United States received paracervical block during labor in 2001.3 Paracervical block remains more popular in Scandinavian countries. Approximately 17% of Finnish parturients received paracervical block during labor in 2004-2005.4 In the United States, the decline in the popularity of paracervical block has resulted from both fear of fetal complications and the greater popularity of neuraxial analgesic techniques.

Jensen et al.5 randomly assigned 117 nulliparous women to receive either bupivacaine paracervical block or intramuscular meperidine 75 mg. Women in the paracervical block group had significantly better analgesia than women in the meperidine group at 20, 40, and 60 minutes. During the first 60 minutes, pain relief was complete or acceptable in 78% of the women in the paracervical block group but in only 31% of the women in the meperidine group. Two fetuses in the paracervical block group and one in the meperidine group had transient bradycardia. A total of 6 infants in the paracervical block group and 16 infants in the meperidine group (P < .05) had fetal/neonatal depression, which the investigators defined as an umbilical arterial blood pH of 7.15 or less and/or a 1-minute Apgar score of 7 or less.5 A 2012 Cochrane Review cited this study as evidence that paracervical block provides more effective analgesia during labor than intramuscular meperidine.6

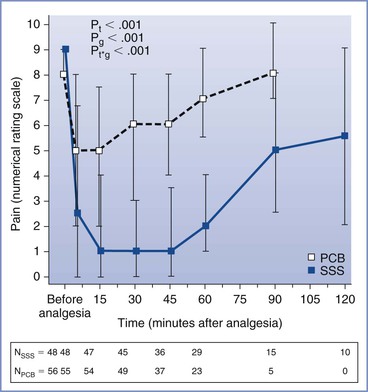

In a recent study, Junttila et al.4 randomly assigned 122 parous women to receive either bupivacaine paracervical block or single-shot spinal bupivacaine with sufentanil. Single-injection spinal analgesia was superior to that provided by paracervical block (Figure 24-1), although paracervical block resulted in a pain score of 3 or less in 43% of the study subjects, and over half of the women in the paracervical block group indicated that they would be happy to receive this method of analgesia during labor in a future pregnancy. There was no difference between the two groups in the incidence of fetal heart rate (FHR) abnormalities, and there were no cases of fetal bradycardia in either group.4

FIGURE 24-1 Pain scores over time before and after paracervical block (10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine) or single-shot spinal (intrathecal) injection of bupivacaine 2.5 mg and sufentanil 2.5 µg. Data are median pain scores with the 25th and 75th percentiles. PCB, paracervical block; SSS, single-shot spinal analgesia; Pt, P-time; Pg, P-groups; Pt*g, P-time*group. N, number of parturients at the measurement time points. (From Junttilla EK, Karjalainen PK, Ohtonen PP, et al. A comparison of paracervical block with single-shot spinal for labour analgesia in multiparous women: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Obstet Anesth 2009; 18:15-21.)

Kangas-Saarela et al.7 compared neonatal neurobehavioral responses in 10 infants whose mothers received bupivacaine paracervical block with those in 12 infants whose mothers received no analgesia. The investigators performed paracervical block while each patient lay in a left lateral position, and they limited the depth of the injection into the vaginal mucosa to 3 mm or less. They observed no significant differences between groups in neurobehavioral responses at 3 hours, 1 day, 2 days, or 4 to 5 days after delivery. These investigators concluded that properly performed paracervical block does not adversely affect newborn infant behavior or neurologic function.7

Technique

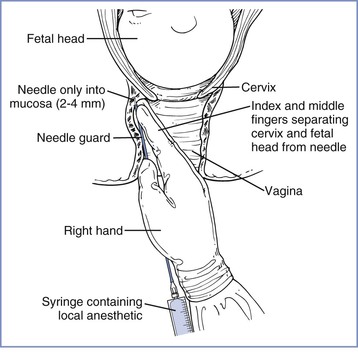

Paracervical block is performed with the patient in a modified lithotomy position. The uterus should be displaced leftward during performance of the block; this displacement may be accomplished by placing a folded pillow beneath the patient’s right buttock. The physician uses a needle guide to define and limit the depth of the injection and to reduce the risk for vaginal or fetal injury. The physician introduces the needle and needle guide into the vagina with the left hand for the left side of the pelvis and with the right hand for the right side (Figure 24-2). The needle and needle guide are introduced into the left or right lateral vaginal fornix, near the cervix, at the 4-o’clock or the 8-o’clock position. The needle is advanced through the vaginal mucosa to a depth of 2 to 3 mm.8 The physician should aspirate before each injection of local anesthetic. A total of 5 to 10 mL of local anesthetic, without epinephrine, is injected on each side.9 Some obstetricians recommend giving incremental doses of local anesthetic on each side (e.g., 2.5 to 5 mL of local anesthetic between the 3-o’clock and 4-o’clock positions, followed by 2.5 to 5 mL between the 4-o’clock and 5-o’clock positions).8,10,11

FIGURE 24-2 Technique of paracervical block. Notice the position of the hand and fingers in relation to the cervix and fetal head. No undue pressure is applied at the vaginal fornix by the fingers or the needle guide, and the needle is inserted to a shallow depth. (Redrawn from Abouleish E. Pain Control in Obstetrics. New York, JB Lippincott, 1977:344.)

After injecting the local anesthetic in either the left or right lateral vaginal fornix, the physician should wait 5 to 10 minutes and observe the FHR before injecting the local anesthetic on the other side.11 Some obstetricians do not endorse this recommendation. Van Dorsten et al.12 randomly assigned 42 healthy parturients at term to either of two methods of paracervical block. The study group experienced a 10-minute interval between injections of local anesthetic on the left and right sides of the vagina. The control group had almost simultaneous injections on the left and right sides. No cases of fetal bradycardia occurred in either group. The investigators concluded that patient selection and lateral positioning after the block have a more important role in the prevention of post–paracervical block fetal bradycardia than spacing the injections of local anesthetic. However, because they studied only 42 patients and had no cases of fetal bradycardia in either group, they could not exclude the possibility that incremental injection might reduce the incidence of fetal bradycardia in a larger series of patients.

Choice of Local Anesthetic

The physician should administer small volumes of a dilute solution of local anesthetic. There is no reason to inject more than 10 mL of local anesthetic on each side. Further, there is no indication for the use of concentrated solutions, such as 2% lidocaine, 0.5% bupivacaine, or 3% 2-chloroprocaine. Nieminen and Puolakka13 observed that paracervical block with 10 mL of 0.125% bupivacaine (5 mL on each side) provided analgesia similar to that provided by 10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine.

The choice of local anesthetic is controversial. The North American manufacturers of bupivacaine have stated that bupivacaine is contraindicated for the performance of paracervical block. In contrast, many European obstetricians—especially those in Finland—have expressed a preference for bupivacaine for this procedure. Bupivacaine has greater cardiotoxicity than other local anesthetic agents, and some investigators have suggested that its use leads to a higher incidence of fetal bradycardia or adverse outcome than use of other local anesthetics for paracervical block. In a review of 50 cases of perinatal death associated with paracervical block, Teramo14 found that the local anesthetic was bupivacaine in at least 29 of the 50 cases.

Palomäki et al.15 hypothesized that levobupivacaine might result in a lower incidence of post–paracervical block fetal bradycardia than racemic bupivacaine. In a randomized double-blind study of 397 laboring women, paracervical block was performed with 10 mL of either 0.25% levobupivacaine or 0.25% racemic bupivacaine. The incidence of transient FHR abnormalities was 10.4% in the levobupivacaine group and 12.8% in the racemic bupivacaine group, and that of fetal bradycardia was 2.6% in the levobupivacaine group and 3.8% in the racemic bupivacaine group (P = NS).

Some physicians have suggested that 2-chloroprocaine is the local anesthetic of choice for paracervical block. Published studies suggest but do not prove that post–paracervical block fetal bradycardia occurs less frequently with 2-chloroprocaine than with amide local anesthetics.10,16–18 Weiss et al.16 performed a double-blind study in which 60 patients were randomly assigned to receive 20 mL of either 2% 2-chloroprocaine or 1% lidocaine for paracervical block. Bradycardia occurred in 1 of the 29 fetuses in the 2-chloroprocaine group, compared with 5 of 31 fetuses in the lidocaine group (P = .14). LeFevre18 retrospectively observed that fetal bradycardia occurred after 2 (6%) of 33 paracervical blocks performed with 2-chloroprocaine versus 44 (12%) of 361 paracervical blocks performed with mepivacaine (P = .29).

2-Chloroprocaine undergoes rapid enzymatic hydrolysis. Thus it has the shortest intravascular half-life among the local anesthetics used clinically. This rapid metabolism seems advantageous in the event of unintentional intravascular or fetal injection. Philipson et al.17 performed paracervical block with 10 mL of 1% 2-chloroprocaine in 16 healthy parturients. At delivery, only trace concentrations of 2-chloroprocaine were detected in one (6%) of the maternal blood samples and four (25%) of the umbilical cord venous blood samples. The investigators concluded17:

In all of the studies of paracervical block with 2-chloroprocaine, there were no cases in which the abnormal fetal heart rate patterns were associated with depressed neonates. This is in contrast to the studies with amide local anesthetics and may be explained by the rapid enzymatic inactivation of 2-chloroprocaine.

Some obstetricians dislike 2-chloroprocaine because of its relatively short duration of action. However, in one study the mean duration of analgesia was 40 minutes after paracervical administration of either 2-chloroprocaine or lidocaine.16 A 2012 Cochrane Review concluded that the choice of local anesthetic agent did not affect maternal satisfaction with pain relief after paracervical block.6

Maternal Complications

Maternal complications of paracervical block are uncommon but may be serious (Box 24-1).19–22 Systemic local anesthetic toxicity may result from direct intravascular injection or rapid systemic absorption of the local anesthetic. Postpartum neuropathy may follow direct sacral plexus trauma, or it may result from hematoma formation. Retropsoal and subgluteal abscesses are rare but may result in maternal morbidity or mortality.21,22

Fetal Complications

In some cases, fetal injury results from direct injection of local anesthetic into the fetal scalp during paracervical block.23 Fetal scalp injection of 10 or 20 mL of local anesthetic undoubtedly causes systemic local anesthetic toxicity, which may result in fetal death. Fetal scalp injection seems more likely to occur when the obstetrician performs paracervical block in the presence of advanced (i.e., > 8 cm) cervical dilation.

Bradycardia is the most common fetal complication. Fetal bradycardia typically develops within 2 to 10 minutes after the injection of local anesthetic. Most cases resolve within 5 to 10 minutes, but some cases of bradycardia persist for as long as 30 minutes. Published studies have noted an incidence of bradycardia that varies between 0% and 70%.4,11,18,24–31 These figures represent extremes on either side of the true incidence of this complication. Some studies have overstated the problem by defining bradycardia as a baseline FHR of less than 120 bpm. (A baseline FHR of 110 bpm does not necessarily indicate fetal compromise.) Experienced obstetricians clearly do not encounter clinically significant fetal bradycardia after 70% of their paracervical blocks. It is equally clear that the incidence of clinically significant fetal bradycardia is not zero, and it is difficult to teach this technique without placing some fetuses at risk.

Shnider et al.26 reported that fetal bradycardia occurred after 24% of 845 paracervical blocks administered to 705 patients with either 1% mepivacaine, 1% lidocaine, or 1% propitocaine (prilocaine). Neonatal depression occurred significantly more often in infants who had FHR changes after paracervical block than in a control group or in a group of infants with no FHR changes after paracervical block. In contrast, Carlsson et al.27 performed 523 paracervical blocks with 0.125% or 0.25% bupivacaine in 469 women. Of the total, nine (1.9%) fetuses had bradycardia, but at delivery all nine of the newborns had a 5-minute Apgar score of 9 or 10.

Goins28 observed fetal bradycardia in 24 (13%) of 182 patients who received paracervical block with 20 mL of 1% mepivacaine. He compared neonatal outcome for these patients with neonatal outcome for 343 patients who received other analgesic/anesthetic techniques. There was a slightly higher incidence of low Apgar scores at 1 minute and 5 minutes in the paracervical block group, but the difference was not statistically significant. LeFevre18 observed fetal bradycardia after 46 (11%) of 408 paracervical blocks. Fetal bradycardia was more common in those patients with a nonreassuring FHR tracing before the performance of paracervical block.

In a review of four randomized controlled trials published between 1975 and 2000, Rosen30 estimated that the incidence of post–paracervical block fetal bradycardia is 15%. More recently, Volmanen et al.31 reviewed four studies of paracervical block that had adequate sample size (n > 200), used the superficial injection technique, and administered 0.125% or 0.25% bupivacaine. Among the 1361 patients in these four studies, the incidence of fetal bradycardia was 2.2%. The observed episodes of fetal bradycardia were transient and did not require emergency cesarean delivery.31

Etiology of Fetal Bradycardia

The etiology of fetal bradycardia after paracervical block is unclear. Investigators have offered at least four theories that might explain the etiology of fetal bradycardia, as discussed here.

Reflex Bradycardia.

Manipulation of the fetal head, the uterus, or the uterine blood vessels during performance of the block may cause reflex fetal bradycardia.25

Direct Fetal Central Nervous System and Myocardial Depression.

The performance of paracervical block results in the injection of large volumes of local anesthetic close to the uteroplacental circulation. Local anesthetic rapidly crosses the placenta32 and may cause fetal central nervous system (CNS) depression, myocardial depression, and/or umbilical vasoconstriction. Puolakka et al.33 observed that the most common abnormality after paracervical block was the disappearance of FHR accelerations. They speculated that FHR changes result from rapid transplacental passage of local anesthetic into the fetal circulation, followed by a direct toxic effect of the local anesthetic on the FHR regulatory centers.

Some investigators have suggested that fetal bradycardia results from a direct toxic effect of the local anesthetic on the fetal heart.34,35 Shnider et al.34 reported that in four cases of fetal bradycardia, mepivacaine concentrations in fetal scalp blood were higher than peak concentrations in maternal arterial blood. Asling et al.35 made similar observations in six of seven cases of fetal bradycardia. They suggested that local anesthetic reaches the fetus by a more direct route than maternal systemic absorption, and they speculated that high fetal concentrations of local anesthetic result from local anesthetic diffusion across the uterine arteries. This would lead to local anesthetic concentrations in intervillous blood that are higher than concentrations in maternal brachial arterial blood. High fetal concentrations would then occur from the passive diffusion of local anesthetic across the placenta.

High fetal concentrations of local anesthetic also may result from fetal acidosis and ion trapping.36,37 Local anesthetics are weak bases, and if acidosis develops in a fetus, increasing amounts of local anesthetic will cross the placenta regardless of the site of maternal injection. It is also possible that the obstetrician may directly inject local anesthetic into uterine blood vessels.

Most studies have noted that local anesthetic concentrations in the fetus are consistently lower than those in the mother after paracervical block.9 Further, fetal bradycardia has not consistently occurred in documented cases of fetal local anesthetic toxicity. Freeman et al.38 injected 300 mg of mepivacaine directly into the scalp of two anencephalic fetuses. The QRS complex widened, the PR interval lengthened, and both fetuses died, but fetal bradycardia did not occur before fetal death. In contrast, the investigators observed no widening of the QRS complex or lengthening of the PR interval in normal fetuses demonstrating bradycardia after paracervical block. Rather, the fetal electrocardiogram (ECG) changes were consistent with sinoatrial node suppression with a wandering atrial pacemaker. The investigators concluded that a mechanism other than direct fetal myocardial depression is responsible for fetal bradycardia after paracervical block.

Increased Uterine Activity.

Increased uterine activity results in decreased uteroplacental perfusion. Fishburne et al.39 noted that direct uterine arterial injection of bupivacaine consistently caused a significant increase in uterine tone in gravid ewes. Uterine arterial injection of 2-chloroprocaine did not affect myometrial tone, whereas injection of lidocaine had an intermediate effect.

Myometrial injection of a local anesthetic also may cause greater uterine activity. Morishima et al.40 performed paracervical block with either lidocaine or 2-chloroprocaine in pregnant baboons with normal and acidotic fetuses. A transient increase in uterine activity and a significant reduction in uterine blood flow occurred after paracervical block in 73% of the mothers. Approximately 33% of the normal fetuses and all of the acidotic fetuses had bradycardia after paracervical block. The acidotic fetuses had more severe bradycardia, greater hypoxemia, and slower recovery of oxygenation compared with fetuses that were well oxygenated before paracervical block. The researchers concluded that post–paracervical block fetal bradycardia is in part a result of greater uterine activity, diminished uteroplacental perfusion, and decreased oxygen delivery to the fetus. They also concluded that paracervical block should be avoided in the presence of fetal compromise.

Uterine and/or Umbilical Artery Vasoconstriction.

The deposition of local anesthetic in close proximity to the uterine arteries may cause uterine artery vasoconstriction, with a subsequent drop in uteroplacental perfusion. At least two studies noted that lidocaine and mepivacaine caused vasoconstriction of human uterine arteries in vitro.41,42 (These studies were performed before recognition of the importance of intact endothelium during investigation of vascular smooth muscle response.) Similarly, Norén et al.43,44 noted that bupivacaine caused concentration-dependent contraction of uterine arterial smooth muscle from rats and pregnant women. The calcium entry–blocking drugs verapamil and nifedipine decreased the vascular smooth muscle contraction caused by bupivacaine. The researchers concluded that the use of bupivacaine for paracervical block may cause uterine artery vasoconstriction, especially when the bupivacaine is injected close to the uterine arteries. Further, they suggested that the administration of a calcium entry–blocking drug may successfully eliminate this vasoconstrictive effect of bupivacaine. (Although these studies were performed in 1991, the researchers did not mention whether they preserved, removed, or even observed the presence of the vascular endothelium. The presence of vascular endothelium may alter the response of vascular smooth muscle to local anesthetics.45)

Greiss et al.46 observed that intra-aortic injection of lidocaine or mepivacaine led to decreased uterine blood flow in gravid ewes. Similarly, Fishburne et al.39 noted that direct uterine arterial injection of lidocaine, bupivacaine, or 2-chloroprocaine reduced uterine blood flow in gravid ewes. They concluded that only paracervical block “would be expected to produce the high, sustained uterine arterial concentrations of anesthetic drugs that cause the significant reductions in uterine blood flow which we now feel are the etiology of fetal bradycardia.”39 In a later study, Manninen et al.47 observed that paracervical injection of 10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine led to an increase in the uterine artery pulsatility index—an estimate of uterine vascular resistance—in healthy nulliparous women, suggesting that paracervical block may result in uterine artery vasoconstriction.

In contrast, Puolakka et al.33 used 133Xe to measure intervillous blood flow before and after the performance of paracervical block with 10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine in 10 parturients. They observed no decrease in mean intervillous blood flow in these patients. Further, they noted minimal change in intervillous blood flow in the three patients who had fetal bradycardia after paracervical block. Using Doppler ultrasonography, Räsänen and Jouppila48 observed no significant change in either uterine or umbilical artery pulsatility index after the performance of paracervical block with 10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine in 12 healthy parturients. However, fetal bradycardia occurred in two patients, and in those two cases, a marked increase in umbilical artery pulsatility index occurred.

Baxi et al.49 performed paracervical block with 20 mL of 1% lidocaine in 10 pregnant women. They observed a decrease in fetal transcutaneous PO2 5 minutes after injecting lidocaine in each of the 10 patients. There was a maximum decline in transcutaneous PO2 at 11.5 minutes, and transcutaneous PO2 returned to baseline by approximately 31 minutes. Some of the patients had increased uterine activity after paracervical block. In contrast, Jacobs et al.50 observed a consistent, sustained decrease in fetal transcutaneous PO2 after only 1 of 10 paracervical blocks performed with 10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine. These investigators attributed their good results to the following precautions: (1) performance of paracervical block only in healthy mothers with normal pregnancies; (2) administration of a small dose of bupivacaine; (3) a limited depth of injection; (4) administration of bupivacaine in four incremental injections (i.e., two injections on each side); and (5) use of the left lateral position immediately after performance of the block. In a later study, Kaita et al.51 observed that paracervical injection of 10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine in 10 healthy parturients resulted in a slight (clinically insignificant) increase in fetal SaO2 as measured by fetal pulse oximetry.

Summary

Most observers currently believe that post–paracervical block bradycardia results from reduced uteroplacental and/or fetoplacental perfusion. Reduction in uteroplacental perfusion may occur because of increased uterine activity and/or a direct vasoconstrictive effect of the local anesthetic. Likewise, decreased umbilical cord blood flow may result from increased uterine activity and/or umbilical cord vasoconstriction. Regardless of the etiology, the severity and duration of fetal bradycardia correlate with the incidence of fetal acidosis and subsequent neonatal depression. Freeman et al.38 reported a significant drop in pH and a rise in base deficit only in fetuses with bradycardia of longer than 10 minutes’ duration. In an observational study of paracervical block and nalbuphine analgesia during labor, Levy et al.52 observed no association between paracervical block and low umbilical arterial blood pH at delivery.

Physician Complications

The performance of paracervical block requires the physician to make several blind needle punctures within the vagina. The needle guide does not consistently protect the physician from a needle-stick injury. Thus, the performance of paracervical block may entail the risk for physician exposure to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or another infectious agent.

Recommendations

It is difficult for me to offer enthusiasm for the performance of paracervical block in contemporary obstetric practice. Nonetheless, paracervical block may be an appropriate technique in circumstances in which neuraxial analgesia is contraindicated or unavailable. The following recommendations seem reasonable:

3. Do not perform paracervical block when the cervix is dilated 8 cm or more.

4. Establish intravenous access before performing paracervical block.

5. Maintain left uterine displacement while performing the block.

6. Limit the depth of injection to approximately 3 mm.

7. Aspirate before each injection of local anesthetic.

10. Avoid the administration of epinephrine-containing local anesthetic solutions.

Lumbar Sympathetic Block

In 1933, Cleland53 demonstrated that lower uterine and cervical visceral afferent sensory fibers join the sympathetic chain at L2 to L3. Subsequently, lumbar sympathetic block was used as an effective—if not popular—method of first-stage analgesia in some hospitals.54–57 Like paracervical block, paravertebral lumbar sympathetic block interrupts the transmission of pain impulses from the cervix and lower uterine segment to the spinal cord. Lumbar sympathetic block provides analgesia during the first stage of labor but does not relieve pain during the second stage. It provides analgesia comparable to that provided by paracervical block but with less risk for fetal bradycardia.

Lumbar sympathetic block may have a favorable effect on the progress of labor. Hunter58 reported that lumbar sympathetic block accelerated labor in 20 of 39 patients with a normal uterine contractile pattern before performance of the block. (Indeed, some of the patients in that study had a 5- to 15-minute period of uterine hypertonus after the block.) Further, he observed that lumbar sympathetic block converted an abnormal uterine contractile pattern to a normal pattern in 14 of 19 patients. He concluded that lumbar sympathetic block represents “one of the most reliable methods reported to actively convert an abnormal labor pattern to a normal pattern.”58 In a later study, Leighton et al.59 randomly assigned 39 healthy nulliparous women at term to receive either epidural analgesia or lumbar sympathetic block. The women who received lumbar sympathetic block had a more rapid rate of cervical dilation during the first 2 hours of analgesia, a shorter second stage of labor, and a nonsignificant trend toward a lower incidence of cesarean delivery for dystocia. However, there was no difference between the groups in the rate of cervical dilation during the active phase of the first stage of labor.

Anesthesiologists may successfully perform lumbar sympathetic block when a history of previous back surgery precludes the successful administration of epidural analgesia.60 Some anesthesiologists offer lumbar sympathetic block to prepared childbirth enthusiasts who desire first-stage analgesia without any motor block or loss of perineal sensation. Meguiar and Wheeler61 stated that the primary usefulness of lumbar sympathetic block is “in cases where continuous lumbar epidural analgesia is refused or contraindicated.” They administered 20 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine to 40 nulliparous women. Among these women, 38 experienced good analgesia, and 28 delivered before resolution of the block. Pain recurred before delivery in the remaining 12 women; the mean duration of analgesia was 283 ± 103 minutes among these patients.61 Leighton et al.59 administered the same dose of bupivacaine, but they observed a shorter duration of analgesia than that observed by Meguiar and Wheeler.61

During the last three decades, lumbar sympathetic block has all but disappeared from obstetric anesthesia practice in the United States, for several reasons. Anesthesiologists may minimize motor block during epidural analgesia by giving a dilute solution of local anesthetic, with or without an opioid. For those few patients who want to retain full perineal sensation, anesthesiologists may give an opioid alone, either intrathecally or epidurally. Thus, there are few patients for whom lumbar sympathetic block holds unique advantages. Further, the procedure often is painful, and few anesthesiologists have acquired and maintained proficiency in performing lumbar sympathetic block in obstetric patients.

Lumbar sympathetic block remains an attractive technique in a small number of patients.60 Alternatively, two recent reports have described the performance of bilateral lower thoracic paravertebral block in a total of five laboring women in whom epidural analgesia was contraindicated.62,63 As anesthesiologists gain greater proficiency with thoracic paravertebral block for patients undergoing breast surgery, perhaps this technique will be used more often in parturients for whom neuraxial analgesia is contraindicated.

Technique

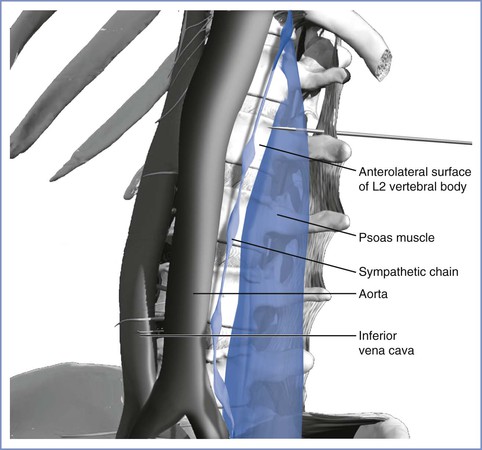

With the patient in the sitting position, a 10-cm, 22-gauge needle is used to identify the transverse process on one side of the second lumbar vertebra. The needle is then withdrawn, redirected, and advanced another 5 cm so that the tip of the needle is at the anterolateral surface of the vertebral column, just anterior to the medial attachment of the psoas muscle (Figure 24-3). It is possible to place the needle within a blood vessel or the subarachnoid space; thus, the anesthesiologist must aspirate before injecting the local anesthetic. Two 5-mL increments of a dilute solution of local anesthetic (with or without epinephrine) are then injected, and the procedure is repeated on the opposite side of the vertebral column.

FIGURE 24-3 Lateral view of needle placement for lumbar sympathetic block. The needle has been advanced so that the tip of the needle is near the anterolateral surface of the L2 vertebral body. The figure illustrates the proximity of the aorta. (Drawing by Naveen Nathan, MD, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL.)

Complications

Modest hypotension occurs in 5% to 15% of patients.58,59,61 The risk for hypotension may be reduced by giving 500 mL of lactated Ringer’s solution intravenously before performing the block. Less common maternal complications are systemic local anesthetic toxicity, total spinal anesthesia, retroperitoneal hematoma, Horner’s syndrome,64 and post–dural puncture headache.65

Fetal complications are unlikely unless hypotension or increased uterine activity results in decreased uteroplacental perfusion.

Pudendal Nerve Block

During the second stage of labor, pain results from distention of the lower vagina, vulva, and perineum. The pudendal nerve, which includes somatic nerve fibers from the anterior primary divisions of the second, third, and fourth sacral nerves, represents the primary source of sensory innervation for the lower vagina, vulva, and perineum. The pudendal nerve also provides motor innervation to the perineal muscles and to the external anal sphincter.

In 1916, King66 reported the use of pudendal nerve block for vaginal delivery. This procedure did not become popular until 1953 and 1954, when Klink67 and Kohl68 described the anatomy and reported modified techniques. Obstetricians often perform pudendal nerve block in patients without epidural or spinal analgesia. The goal is to block the pudendal nerve distal to its formation by the anterior divisions of S2 to S4 but proximal to its division into its terminal branches (i.e., dorsal nerve of the clitoris, perineal nerve, and inferior hemorrhoidal nerve). Pudendal nerve block may provide satisfactory anesthesia for spontaneous vaginal delivery and perhaps for outlet-forceps delivery, but it provides inadequate anesthesia for mid-forceps delivery, postpartum examination and repair of the upper vagina and cervix, and manual exploration of the uterine cavity.69

Efficacy and Timing

The efficacy of pudendal nerve block varies according to the experience of the obstetrician. Unilateral or bilateral failure is common. Thus, obstetricians typically perform simultaneous infiltration of the perineum, especially if the performance of pudendal nerve block is delayed until delivery. Scudamore and Yates70 reported bilateral success rates of approximately 50% after use of the transvaginal route and of approximately 25% after use of the transperineal route. They concluded70:

The term “pudendal block” is often a misnomer.… If this limitation were more widely appreciated, then many mothers would be spared the unnecessary pain which is caused when relatively complicated procedures are attempted under inadequate anesthesia.

In the United States, most obstetricians perform pudendal nerve block immediately before delivery. This practice reflects their concern that perineal anesthesia prolongs the second stage of labor. An advantage to early pudendal nerve block is that the obstetrician may repeat the block on one or both sides if it should fail, provided that the maximum safe dose of local anesthetic is not exceeded. European obstetricians seem more willing to perform pudendal nerve block at the onset of the second stage of labor. Langhoff-Roos and Lindmark71 administered pudendal nerve block before or just after complete cervical dilation in 551 (64%) of 865 women. In a nonrandomized study, Zador et al.72 evaluated obstetric outcome in 24 patients who received pudendal nerve block when the cervix was completely dilated and in 24 patients who did not receive pudendal block. Pudendal nerve block slightly prolonged the second stage of labor, but it did not increase the incidence of instrumental vaginal delivery.72

It is barbaric to withhold analgesia during the second stage of labor. Obstetricians need not delay the administration of pudendal nerve block until delivery. Rather, for those patients without epidural or spinal analgesia, it seems appropriate to perform pudendal nerve block when the patient complains of vaginal and perineal pain. A 2004 study suggested that pudendal nerve block does not provide reliable analgesia during the second stage of labor but has greater efficacy for episiotomy and repair.73 In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, Aissaoui et al.74 observed that unilateral, nerve stimulator–guided pudendal nerve block with ropivacaine was associated with decreased pain and less need for supplemental analgesia during the first 48 hours after performance of mediolateral episiotomy at vaginal delivery.

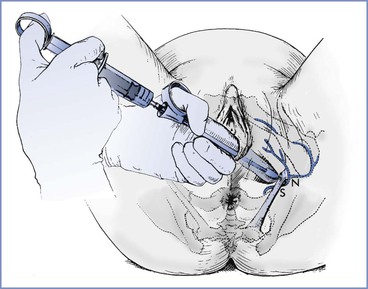

Technique

The transvaginal approach is more popular than the transperineal approach in the United States. The obstetrician uses a needle guide (either the Iowa trumpet or the Kobak needle guide) to prevent injury to the vagina and fetus. In contrast to the technique for paracervical block, the needle must protrude 1.0 to 1.5 cm beyond the needle guide to allow adequate penetration for injection of the local anesthetic. The obstetrician introduces the needle and needle guide into the vagina with the left hand for the left side of the pelvis and with the right hand for the right side (Figure 24-4). The needle is introduced through the vaginal mucosa and sacrospinous ligament, just medial and posterior to the ischial spine. The pudendal artery lies in close proximity to the pudendal nerve; thus, the obstetrician must aspirate before and during the injection of local anesthetic. The obstetrician typically injects 7 to 10 mL of local anesthetic solution on each side. (Some obstetricians inject 3 mL of local anesthetic just above the ischial spine on each side.75) The obstetrician should pay attention to the total dose of local anesthetic given, especially when repetitive pudendal nerve blocks or both pudendal nerve block and perineal infiltration are performed.

FIGURE 24-4 Local infiltration of the pudendal nerve. Transvaginal technique showing the needle extended beyond the needle guard and passing through the sacrospinous ligament (S) to reach the pudendal nerve (N). (From Cunningham FG, MacDonald PC, Gant NF, et al. Williams Obstetrics. 20th edition. Stamford, CT, Appleton & Lange, 1997:389.)

Choice of Local Anesthetic

Rapid maternal absorption of the local anesthetic occurs after the performance of pudendal nerve block.72,75 Zador et al.72 detected measurable concentrations of lidocaine in maternal venous and fetal scalp capillary blood samples within 5 minutes of the injection of 20 mL of 1% lidocaine. They detected peak concentrations between 10 and 20 minutes after injection. Kuhnert et al.76 reported that after pudendal nerve block, neonatal urine concentrations of lidocaine and its metabolites were similar to those measured in neonatal urine after epidural administration of lidocaine.

Some physicians favor the administration of 2-chloroprocaine. Its rapid onset of action provides an advantage when pudendal nerve block is performed immediately before delivery. Its rapid metabolism and short intravascular half-life lower the likelihood of maternal or fetal systemic toxicity. 2-Chloroprocaine has the disadvantage of a short duration of action. However, if the obstetrician performs pudendal nerve block with 2-chloroprocaine at the onset of the second stage of labor, the block can be repeated as needed. When the block is performed immediately before delivery, the brief duration of action of 2-chloroprocaine is not a disadvantage for the experienced obstetrician.

Merkow et al.77 evaluated neonatal neurobehavior in infants whose mothers received 30 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine, 1% mepivacaine, or 3% 2-chloroprocaine for pudendal nerve block and perineal infiltration before delivery. Neonatal response to pinprick at 4 hours was better in the mepivacaine group; otherwise, there were no significant differences among groups in neurobehavioral scores at 4 and 24 hours after delivery.

Regardless of the choice of local anesthetic, there is no indication for the administration of a concentrated solution. For example, it is unnecessary, and perhaps dangerous, to give 0.5% bupivacaine, 2% lidocaine, or 3% 2-chloroprocaine. Rather, the obstetrician should use 2% 2-chloroprocaine or 1% lidocaine.

Some obstetricians contend that the addition of epinephrine to the local anesthetic solution improves the quality of pudendal nerve block. Langhoff-Roos and Lindmark71 reported a randomized, double-blind study of 865 patients who received pudendal nerve block with 16 mL of 1% mepivacaine, 1% mepivacaine with epinephrine, or 0.25% bupivacaine. Mepivacaine with epinephrine provided effective anesthesia more often and also caused a greater “loss of the urge to bear down” than did the other two local anesthetic solutions. However, there was no significant difference among groups in the duration of the second stage of labor or the incidence of instrumental vaginal delivery. Schierup et al.78 randomly assigned 151 patients to receive pudendal nerve block with 20 mL of 1% mepivacaine either with or without epinephrine. The addition of epinephrine did not improve the quality of anesthesia, but it slightly prolonged the interval between pudendal nerve block administration and delivery. Maternal venous blood mepivacaine concentrations were slightly higher in the no-epinephrine group, but there was no difference between groups in umbilical cord blood concentrations of mepivacaine.

Complications

Maternal complications of pudendal nerve block are uncommon but may be serious (Box 24-2). Systemic local anesthetic toxicity may result from either direct intravascular injection or systemic absorption of an excessive dose of local anesthetic. Toxicity may occur if the obstetrician exceeds the safe dose of local anesthetic during repetitive injections performed to obtain a successful block. Vaginal, ischiorectal, and retroperitoneal hematomas may result from trauma to the pudendal artery.79 These hematomas are typically small and rarely require operative intervention. Subgluteal and retropsoal abscesses are rare but can result in significant morbidity or mortality.21,22

Fetal complications are rare. The primary fetal complications result from fetal trauma and/or direct fetal injection of local anesthetic.

As with paracervical block, the performance of pudendal nerve block requires the obstetrician to make several blind needle punctures within the vagina. The needle guide does not uniformly protect the physician from a needle-stick injury. Thus, performance of pudendal nerve block may entail a risk for physician exposure to HIV or another infectious agent.

Perineal Infiltration

Perineal infiltration is perhaps the most common local anesthetic technique used for vaginal delivery. Given the frequent failure of pudendal nerve block, obstetricians often perform pudendal nerve block and perineal infiltration simultaneously. Perineal infiltration also may be required in patients with incomplete neuraxial anesthesia. The obstetrician injects several milliliters of local anesthetic solution into the posterior fourchette. There are no large nerve fibers to be blocked, so the onset of anesthesia is rapid. However, perineal infiltration provides anesthesia only for episiotomy and repair. Anesthesia is often inadequate even for these limited procedures. Moreover, perineal infiltration provides no muscle relaxation. In a prospective randomized trial, perineal infiltration of saline-placebo provided postpartum analgesia that was equivalent to that provided by infiltration of either ropivacaine or lidocaine in women who underwent mediolateral episiotomy at vaginal delivery.80

Choice of Local Anesthetic

Philipson et al.81 evaluated the pharmacokinetics of lidocaine after perineal infiltration. They gave 1% or 2% lidocaine without epinephrine during the crowning phase of the second stage of labor in 15 healthy parturients. The mean ± SD dose of lidocaine was 79 ± 3 mg, and the mean drug-to-delivery interval was 7.8 ± 7.0 minutes. The investigators detected lidocaine in maternal plasma as early as 1 minute after injection. Peak maternal plasma concentrations of lidocaine occurred between 3 and 15 minutes after injection. Despite the administration of small doses of lidocaine and the short drug-to-delivery intervals, there was rapid placental transfer of significant amounts of lidocaine. The mean fetal-to-maternal lidocaine concentration ratio of 1.32 was significantly higher than the ratio reported after administration of lidocaine for paracervical block, pudendal nerve block, or epidural anesthesia for vaginal or cesarean delivery. There was a significant correlation between the fetal-to-maternal lidocaine concentration ratio and the length of the second stage of labor. These investigators speculated that fetal tissue acidosis increased the fetal-to-maternal lidocaine ratio after perineal infiltration in this study. Finally, they noted the persistence of lidocaine and its pharmacologically active metabolites for at least 48 hours after delivery.81

Subsequently, Philipson et al.82 evaluated the placental transfer of 2-chloroprocaine after perineal administration of 1% or 2% 2-chloroprocaine to 17 women shortly before delivery. The mean ± SD dose of 2-chloroprocaine was 81.8 ± 27.0 mg, and the mean drug-to-delivery interval was 6.7 ± 4.3 minutes. Perineal infiltration of 2-chloroprocaine provided adequate anesthesia for episiotomy repair except in two patients who required additional local anesthetic for repair of fourth-degree lacerations. The investigators did not detect 2-chloroprocaine in maternal plasma after infiltration or at delivery. Further, they detected 2-chloroprocaine at delivery in only one umbilical cord venous blood sample and no 2-chloroprocaine in neonatal plasma. In contrast, they consistently detected the drug’s metabolite, chloroaminobenzoic acid, in maternal plasma, umbilical cord venous plasma, and neonatal urine. The fetal-to-maternal ratio of chloroaminobenzoic acid (0.80) was similar to that reported after the administration of 2-chloroprocaine for paracervical block and epidural anesthesia for cesarean delivery. The investigators suggested that very little, if any, unchanged 2-chloroprocaine reaches the fetus after perineal infiltration. They concluded that 2-chloroprocaine may be preferable to lidocaine for antepartum perineal infiltration.82

Complications

The obstetrician must take care to avoid injecting the local anesthetic into the fetal scalp. Kim et al.83 reported a case of newborn lidocaine toxicity after maternal perineal infiltration of 6 mL of 1% lidocaine before vaginal delivery. Similarly, DePraeter et al.84 reported a case of lidocaine toxicity in a newborn whose mother received perineal infiltration with 10 mL of 2% lidocaine 4 minutes before delivery. In both cases, the infants were initially vigorous but required endotracheal intubation 15 minutes after delivery. No lidocaine was detected in umbilical cord blood, but neonatal blood samples revealed concentrations of 14 µg/mL at 2 hours and 13.8 µg/mL at 6.5 hours. Small scalp puncture wounds suggested that the lidocaine toxicity resulted from direct fetal scalp injection. Pignotti et al.85 reported two cases of neonatal local anesthetic toxicity. In one case, lidocaine and prilocaine cream had been applied to the maternal perineum. In the second case, 10 mL of 2% mepivacaine had been injected into the perineum. Both infants required endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation, but in both cases, neurodevelopmental outcome was normal at 12 months of age. Kim et al.83 suggested that the presence of a molded head in the occiput posterior position may predispose to unintentional direct injection of the fetal scalp. These cases support the recommendation for use of 2-chloroprocaine for perineal infiltration.

References

1. Palomaki O, Huhtala H, Kirkinen P. What determines the analgesic effect of paracervical block? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:962–966.

2. Gibbs CP, Krischer J, Peckham BM, et al. Obstetric anesthesia: a national survey. Anesthesiology. 1986;65:298–306.

3. Bucklin BA, Hawkins JL, Anderson JR, Ullrich FA. Obstetric anesthesia workforce survey: twenty-year update. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:645–653.

4. Junttila EK, Karjalainen PK, Ohtonen PP, et al. A comparison of paracervical block with single-shot spinal for labour analgesia in multiparous women: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2009;18:15–21.

5. Jensen F, Qvist I, Brocks V, et al. Submucous paracervical blockade compared with intramuscular meperidine as analgesia during labor: a double-blind study. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;64:724–727.

6. Novikova N, Cluver C. Local anaesthetic nerve block for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(4).

7. Kangas-Saarela T, Jouppila R, Puolakka J, et al. The effect of bupivacaine paracervical block on the neurobehavioural responses of newborn infants. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1988;32:566–570.

8. Jägerhorn M. Paracervical block in obstetrics: an improved injection method. A clinical and radiological study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1975;54:9–27.

9. Cibils LA, Santonja-Lucas JJ. Clinical significance of fetal heart rate patterns during labor. III. Effect of paracervical block anesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1978;130:73–100.

10. Freeman DW, Arnold NI. Paracervical block with low doses of chloroprocaine: fetal and maternal effects. JAMA. 1975;231:56–57.

11. King JC, Sherline DM. Paracervical and pudendal block. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1981;24:587–595.

12. Van Dorsten JP, Miller FC, Yeh SY. Spacing the injection interval with paracervical block: a randomized study. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;58:696–702.

13. Nieminen K, Puolakka J. Effective obstetric paracervical block with reduced dose of bupivacaine: a prospective randomized double-blind study comparing 25 mg (0.25%) and 12.5 mg (0.125%) of bupivacaine. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76:50–54.

14. Teramo K. Effects of obstetrical paracervical blockade on the fetus. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1971;16(Suppl):1–55.

15. Palomäki O, Huhtala H, Kirkinen P. A comparative study of the safety of 0.25% levobupivacaine and 0.25% racemic bupivacaine for paracervical block in the first stage of labor. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:956–961.

16. Weiss RR, Halevy S, Almonte RO, et al. Comparison of lidocaine and 2-chloroprocaine in paracervical block: clinical effects and drug concentrations in mother and child. Anesth Analg. 1983;62:168–173.

17. Philipson EH, Kuhnert BR, Syracuse CB, et al. Intrapartum paracervical block anesthesia with 2-chloroprocaine. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;146:16–22.

18. LeFevre ML. Fetal heart rate pattern and postparacervical fetal bradycardia. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;64:343–346.

19. Gaylord TG, Pearson JW. Neuropathy following paracervical block in the obstetric patient. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;60:521–525.

20. Mercado AO, Naz JF, Ataya KM. Postabortal paracervical abscess as a complication of paracervical block anesthesia: a case report. J Reprod Med. 1989;34:247–249.

21. Hibbard LT, Snyder EN, McVann RM. Subgluteal and retropsoal infection in obstetric practice. Obstet Gynecol. 1972;39:137–150.

22. Svancarek W, Chirino O, Schaefer G, Blythe JG. Retropsoas and subgluteal abscesses following paracervical and pudendal anesthesia. JAMA. 1977;237:892–894.

23. Chase D, Brady JP. Ventricular tachycardia in a neonate with mepivacaine toxicity. J Pediatr. 1977;90:127–129.

24. Teramo K, Widholm O. Studies of effect of anaesthetics on foetus. I. The effect of paracervical block with mepivacaine upon foetal acid-base values. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1957;46(Suppl 2):1–39.

25. Rogers RE. Fetal bradycardia associated with paracervical block anesthesia in labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1970;106:913–916.

26. Shnider SM, Asling JH, Holl JW, Margolis AJ. Paracervical block anesthesia in obstetrics. I. Fetal complications and neonatal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1970;107:619–625.

27. Carlsson BM, Johansson M, Westin B. Fetal heart rate pattern before and after paracervical anesthesia: a prospective study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1987;66:391–395.

28. Goins JR. Experience with mepivacaine paracervical block in an obstetric private practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:342–345.

29. Ranta P, Jouppila P, Spalding M, et al. Paracervical block: a viable alternative for labor pain relief? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1995;74:122–126.

30. Rosen MA. Paracervical block for labor analgesia: a brief historic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:S127–S130.

31. Volmanen P, Palomäki O, Ahonen J. Alternatives to neuraxial analgesia for labor. Curr Opin Anesthesiol. 2011;24:235–241.

32. Gordon HR. Fetal bradycardia after paracervical block: correlation with fetal and maternal blood levels of local anesthetic (mepivacaine). N Engl J Med. 1968;279:910–914.

33. Puolakka J, Jouppila R, Jouppila P, Puukka M. Maternal and fetal effects of low-dosage bupivacaine paracervical block. J Perinat Med. 1984;12:75–84.

34. Shnider SM, Asling JH, Margolis AJ, et al. High fetal blood levels of mepivacaine and fetal bradycardia (letter). N Engl J Med. 1968;279:947–948.

35. Asling JH, Shnider SM, Margolis AJ, et al. Paracervical block anesthesia in obstetrics. II. Etiology of fetal bradycardia following paracervical block anesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1970;107:626–634.

36. Brown WU Jr, Bell GC, Alper MH. Acidosis, local anesthetics, and the newborn. Obstet Gynecol. 1976;48:27–30.

37. Biehl D, Shnider SM, Levinson G, Callender K. Placental transfer of lidocaine: effects of fetal acidosis. Anesthesiology. 1978;48:409–412.

38. Freeman RK, Gutierrez NA, Ray ML, et al. Fetal cardiac response to paracervical block anesthesia. I. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;113:583–591.

39. Fishburne JI, Greiss FC, Hopkinson R, Rhyne AL. Responses of the gravid uterine vasculature to arterial levels of local anesthetic agents. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;133:753–761.

40. Morishima HO, Covino BG, Yeh MN, et al. Bradycardia in the fetal baboon following paracervical block anesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;140:775–780.

41. Cibils LA. Response of human uterine arteries to local anesthetics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;126:202–210.

42. Gibbs CP, Noel SC. Response of arterial segments from gravid human uterus to multiple concentrations of lignocaine. Br J Anaesth. 1977;49:409–412.

43. Norén H, Lindblom B, Källfelt B. Effects of bupivacaine and calcium antagonists on the rat uterine artery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1991;35:77–80.

44. Norén H, Lindblom B, Källfelt B. Effects of bupivacaine and calcium antagonists on human uterine arteries in pregnant and non-pregnant women. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1991;35:488–491.

45. Halevy S, Freese KJ, Liu-Barnett M, Altura BM. Endothelium-dependent local anesthetics action on umbilical vessels. FASEB J. 1991;5:A1421.

46. Greiss FC Jr, Still JG, Anderson SG. Effects of local anesthetic agents on the uterine vasculatures and myometrium. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;124:889–899.

47. Manninen T, Aantaa R, Salonen M, et al. A comparison of the hemodynamic effects of paracervical block and epidural anesthesia for labor analgesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2000;44:441–445.

48. Räsänen J, Jouppila P. Does a paracervical block with bupivacaine change vascular resistance in uterine and umbilical arteries? J Perinat Med. 1994;22:301–308.

49. Baxi LV, Petrie RH, James LS. Human fetal oxygenation following paracervical block. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;135:1109–1112.

50. Jacobs R, Stålnacke B, Lindberg B, Rooth G. Human fetal transcutaneous PO2 during paracervical block. J Perinat Med. 1982;10:209–214.

51. Kaita TM, Nikkola EM, Rantala MI, et al. Fetal oxygen saturation during epidural and paracervical analgesia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:336–340.

53. Cleland JGP. Paravertebral anaesthesia in obstetrics: experimental and clinical basis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1933;57:51–62.

54. Shumacker HB, Manahan CP, Hellman LM. Sympathetic anesthesia in labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1943;45:129.

55. Jarvis SM. Paravertebral sympathetic nerve block: a method for the safe and painless conduct of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1944;47:335–342.

56. Reich AM. Paravertebral lumbar sympathetic block in labor: a report on 500 deliveries by a fractional procedure producing continuous conduction anesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1951;61:1263–1276.

57. Cleland JGP. Continuous peridural and caudal analgesia in obstetrics. Analg Anesth. 1949;28:61–76.

58. Hunter CA Jr. Uterine motility studies during labor: observations on bilateral sympathetic nerve block in the normal and abnormal first stage of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1963;85:681–686.

59. Leighton BL, Halpern SH, Wilson DB. Lumbar sympathetic blocks speed early and second stage induced labor in nulliparous women. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1039–1046.

60. Suelto MD, Shaw DB. Labor analgesia with paravertebral lumbar sympathetic block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1999;4:179–181.

61. Meguiar RV, Wheeler AS. Lumbar sympathetic block with bupivacaine: analgesia for labor. Anesth Analg. 1978;57:486–490.

62. Nair V, Henry R. Bilateral paravertebral block: a satisfactory alternative for labour analgesia. Can J Anesth. 2001;48:179–184.

63. Okutomi T, Taguchi M, Amano K, Hoka S. Paravertebral block for analgesia in a parturient with idiopathic thrombocytopenia. Masui. 2002;51:1123–1126.

64. Wills MH, Korbon GA, Arasi R. Horner’s syndrome resulting from a lumbar sympathetic block. Anesthesiology. 1988;68:613–614.

65. Artuso JD, Stevens RA, Lineberry PJ. Post dural puncture headache after lumbar sympathetic block: a report of two cases. Reg Anesth. 1991;16:288–291.

66. King R. Perineal anesthesia in labor. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1916;23:615–618.

67. Klink EW. Perineal nerve block: an anatomic and clinical study in the female. Obstet Gynecol. 1953;1:137–146.

68. Kohl GC. New method of pudendal nerve block. Northwest Med. 1954;53:1012–1013.

69. Hutchins CJ. Spinal analgesia for instrumental delivery: a comparison with pudendal nerve block. Anaesthesia. 1980;35:376–377.

70. Scudamore JH, Yates MJ. Pudendal block—a misnomer? Lancet. 1966;1:23–24.

71. Langhoff-Roos J, Lindmark G. Analgesia and maternal side effects of pudendal block at delivery: a comparison of three local anesthetics. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1985;64:269–273.

72. Zador G, Lindmark G, Nilsson BA. Pudendal block in normal vaginal deliveries: clinical efficacy, lidocaine concentrations in maternal and foetal blood, foetal and maternal acid-base values and influence on uterine activity. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl. 1974;34:51–64.

73. Pace MC, Aurilio C, Bulletti C, et al. Subarachnoid analgesia in advanced labor: a comparison of subarachnoid analgesia and pudendal block in advanced labor. Analgesic quality and obstetric outcome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1034:356–363.

74. Aissaoui Y, Bruyère R, Mustapha H, et al. A randomized controlled trial of pudendal nerve block for pain relief after episiotomy. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:625–629.

75. Cunningham FG, Leveno KL, Bloom SL, et al. Williams Obstetrics. 22nd edition. McGraw-Hill: New York; 2005.

76. Kuhnert BR, Knapp DR, Kuhnert PM, Prochaska AL. Maternal, fetal, and neonatal metabolism of lidocaine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1979;26:213–220.

77. Merkow AJ, McGuinness GA, Erenberg A, Kennedy RL. The neonatal neurobehavioral effects of bupivacaine, mepivacaine, and 2-chloroprocaine used for pudendal block. Anesthesiology. 1980;52:309–312.

78. Schierup L, Schmidt JF, Jensen AT, Rye BAO. Pudendal block in vaginal deliveries: mepivacaine with and without epinephrine. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1988;67:195–197.

79. Kurzel RB, Au AH, Rooholamini SA. Retroperitoneal hematoma as a complication of pudendal block: diagnosis made by computed tomography. West J Med. 1996;164:523–525.

80. Schinkel N, Colbus L, Soltner C, et al. Perineal infiltration with lidocaine 1%, ropivacaine 0.75%, or placebo for episiotomy repair in parturients who received epidural labor analgesia: a double-blind randomized study. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2010;19:293–297.

81. Philipson EH, Kuhnert BR, Syracuse CD. Maternal, fetal, and neonatal lidocaine levels following local perineal infiltration. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;149:403–407.

82. Philipson EH, Kuhnert BR, Syracuse CD. 2-Chloroprocaine for local perineal infiltration. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:1275–1278.

83. Kim WY, Pomerance JJ, Miller AA. Lidocaine intoxication in a newborn following local anesthesia for episiotomy. Pediatrics. 1979;64:643–645.

84. De Praeter C, Vanhaesebrouch P, De Praeter N, Govaert P. Episiotomy and neonatal lidocaine intoxication (letter). Eur J Pediatr. 1991;150:685–686.

85. Pignotti MS, Indolfi G, Ciuti R, Donzelli G. Perinatal asphyxia and inadvertent neonatal intoxication from local anaesthetics given to the mother during labour. BMJ. 2005;330:34–35.