Airway Management in the Critically Ill Adult

STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF THE NORMAL AIRWAY

ASSESSING ADEQUACY OF THE AIRWAY

PHYSIOLOGIC SEQUELAE AND COMPLICATIONS OF TRACHEAL INTUBATION

CONFIRMING TUBE POSITION IN THE TRACHEA

EXTUBATION IN THE DIFFICULT AIRWAY PATIENT (DECANNULATION)

Structure and Function of the Normal Airway

Critical care staff members require an understanding of structure and function in order to successfully manage the airway and the conditions that may affect it. The relevant information can be gained from a variety of sources.1–5 The airway begins at the nose and oral cavity and continues as the pharynx and larynx, which lead to the trachea (beginning at the lower edge of the cricoid cartilage) and then the bronchial tree. The airway1 provides a pathway for airflow between the atmosphere and the lungs;2 facilitates filtering, humidification, and heating of ambient air before it reaches the lower airway;3 prevents nongaseous material from entering the lower airway;6 and allows phonation by controlling the flow of air through the larynx and oropharynx.4

The Tracheobronchial Tree

The bronchial tree is similar in structure to the trachea. Two main bronchi diverge from the carina. The right main bronchus is shorter, wider, and more vertical and runs close to the pulmonary artery and the azygos vein. The left main bronchus passes under the arch of the aorta, anterior to the esophagus, thoracic duct, and descending aorta.7

Overview of Airway Function

In the nose, inspired gas is filtered, humidified, and warmed before entering the lungs. Resistance to gas flow through the nose is twice that of the mouth, explaining the need to mouth-breathe during exercise when gas flows are high. Warming and humidification continue in the pharynx and tracheobronchial tree. Between the trachea and the alveolar sacs, airways divide 23 times. This network increases the cross-sectional area for the gas exchange process but also reduces the velocity of gas flow. Hairs on the nasal mucosa filter inspired air, trapping particles greater than 10 µm in diameter. Many particles settle on the nasal epithelium. Particles 2 to 10 µm in diameter fall on the mucus-covered bronchial walls (as airflow slows), initiating reflex bronchoconstriction and coughing. Ciliated columnar epithelium lines the respiratory tract from the nose to the respiratory bronchioles (except at the vocal cords). The cilia beat at a frequency of 1000 to 1500 cycles per minute, enabling them to move particles away from the lungs at a rate of 16 mm per minute. Particles less than 2 µm in diameter may reach the alveoli, where they are ingested by macrophages. If ciliary motility is defective as a result of smoking or an inherited disorder (e.g., Kartagener’s syndrome or another ciliary dysmotility syndrome), the “mucus escalator” does not work, so more particles are allowed to reach the alveoli, thereby predisposing the patient to chronic pulmonary inflammation.8

The larynx prevents food and other foreign bodies from entering the trachea. Reflex closure of the glottic inlet occurs during swallowing6 and periods of increased intrathoracic (e.g., coughing, sneezing) or intra-abdominal (e.g., vomiting, micturition) pressure. In unconscious patients, these reflexes are lost, so glottic closure may not occur, increasing the risk of pulmonary aspiration.

Assessing Adequacy of the Airway

Adequacy of the airway should be considered in four aspects:

• Patency. Partial or complete obstruction will compromise ventilation of the lungs and likewise gas exchange.

• Protective reflexes. These reflexes help maintain patency and prevent aspiration of material into the lower airways.

• Inspired oxygen concentration. Gas entering the pulmonary alveoli must have an appropriate oxygen concentration.

• Respiratory drive. A patent, secure airway is of little benefit without the movement of gas between the atmosphere and the pulmonary alveoli effected through the processes of inspiration and expiration.

Patency

Upper airway obstruction has a characteristic presentation in the spontaneously breathing patient: noisy inspiration (stridor), poor expired airflow, intercostal retraction, increased respiratory distress, and paradoxical rocking movements of the thorax and abdomen.9 These resolve quickly if the obstruction is removed. In total airway obstruction, sounds of breathing are absent entirely, owing to complete lack of airflow through the larynx. Airway obstruction may occur in patients with an endotracheal tube (ET) or tracheostomy tube in situ due to mucous plugging or kinking of the tube or the patient’s biting down on a tube placed orally. If such patients are spontaneously breathing, they will have the same symptoms and signs just described. Patients on assisted (positive-pressure) breathing modes will have high inflation pressures, decreased tidal and minute volumes, increased end-tidal carbon dioxide levels, and decreased arterial oxygen saturation.

Protective Reflexes

The upper airway shares a common pathway with the upper gastrointestinal tract.6 Protective reflexes, which exist to safeguard airway patency and to prevent foreign material from entering the lower respiratory tract, involve the epiglottis, the vocal cords, and the sensory supply to the pharynx and larynx.10 Patients who can swallow normally have intact airway reflexes, and normal speech makes absence of such reflexes unlikely. Patients with a decreased level of consciousness (LOC) should be assumed to have inadequate protective reflexes.

Inspired Oxygen Concentration

Oxygen demand is elevated by the increased work of breathing associated with respiratory distress11 and by the increased metabolic demands in critically ill or injured patients. Often, higher inspired oxygen concentrations are required to satisfy tissue oxygen demand and to prevent critical desaturations during maneuvers for managing the airway. A cuffed ET, connected to a supply of oxygen, is a sealed system in which the delivered oxygen concentration also is the inspired concentration. A patient wearing a facemask, however, inspires gas from the mask and surrounding ambient air. Because the patient will generate an initial inspiratory flow in the region of 30 to 60 L per minute, and the fresh gas flow to a mask is on the order of 5 to 15 L per minute, much of the tidal inspiration will be “room air” entrained from around the mask. The entrained room air is likely to dilute the concentration of oxygen inspired to less than 50%, even when 100% oxygen is delivered to the mask.12 This unwelcome reduction in inspired oxygen concentration can be mitigated by (1) using a mask with a reservoir bag, (2) ensuring that the mask is fitted firmly to the patient’s face, (3) using a high rate of oxygen flow to the mask (15 L per minute), and (4) supplying a higher oxygen concentration if not already using 100%.

Respiratory Drive

A patent, protected airway will not produce adequate oxygenation or excretion of carbon dioxide without adequate respiratory drive. Changing arterial carbon dioxide tension (PCO2), by changing H+ concentration in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), stimulates the respiratory center, which in turn controls minute volume and therefore arterial PCO2 (negative feedback).11,13 This assumes that increased respiratory drive can produce an increase in minute ventilation (increased respiratory rate or tidal volume, or both, per breath), which may not occur if respiratory mechanics are disturbed. Brain injury and drugs such as opioids, sedatives, and alcohol are direct-acting respiratory center depressants.

Ventilation can be assessed qualitatively by looking, listening, and feeling. In a spontaneously breathing patient, listening to (and feeling) air movement while looking at the extent, nature, and frequency of thoracic movement will give an impression of ventilation. These parameters may be misleading, however. Objective assessment of minute ventilation requires PCO2 measurement in arterial blood or monitoring of end-tidal carbon dioxide, which can be used as a real-time measure of the adequacy of minute ventilation.13 If respiratory drive or minute ventilation is inadequate, positive-pressure respiratory support may be required, and any underlying factors should be addressed if possible (e.g., depressant effect of sedatives or analgesics).

Management of the Airway

Providing an Adequate Inspired Oxygen Concentration

Although oxygen can be administered via nasal cannula, this method does not ensure delivery of more than 30% to 40% oxygen (at most). Other disadvantages include lack of humidification of gases, patient discomfort with use of flow rates greater than 4 to 6 L per minute, and predisposition to nasal mucosal irritation and potential bleeding.14 Therefore, despite being more intrusive for patients, facemasks are superior for oxygen administration. The three main types of facemasks are shown in Figure 2.1:

• The anesthesia-type facemask (mask A in Fig. 2.1) is a solid mask (with no vents) with a cushioned collar to provide a good seal. It is suitable for providing very high oxygen concentrations (approaching 100%) because entrainment is minimized and the anesthetic circuit normally includes a reservoir of gas. These masks become unacceptable for many awake patients within a few minutes because of the association with heat, moisture, and claustrophobia.

• The simple facemask has vents that allow heat or humidity out but that also entrain room air. These masks have no seal and are relatively loose-fitting. Such masks may have a reservoir bag (approximately 500 mL) sitting inferior to the mask (B2 in Fig. 2.1), or may have no reservoir (B1 in Fig. 2.1). Using a simple facemask, without a reservoir bag, it is difficult to deliver an inspired oxygen concentration in excess of 50% even with tight application and 100% oxygen flow to the mask. Under the same conditions, a simple mask with a reservoir bag can produce an inspired oxygen concentration of about 80%.

• The Venturi mask (C in Fig. 2.1) has vents that entrain a known proportion of ambient air when a set flow of 100% oxygen passes through a Venturi device.14 Thus, the inspired oxygen concentration (usually 24% to 35%) is known.

Establishing a Patent and Secure Airway

Airway Maneuvers

Positioning for Airway Management

In the absence of any concerns about cervical spine stability (e.g., with trauma, rheumatoid arthritis, or severe osteoporosis), raising the patient’s head slightly (5 to 10 cm) by means of a small pillow under the occiput can help in airway management. This adjustment extends the atlanto-occipital joint and moves the oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal axes into better alignment, providing the best straight line to the glottis (“sniffing” position).15,16

Clearing the Airway

Acute airway obstruction in the obtunded patient often due to the tongue or extraneous material—liquid (saliva, blood, gastric contents) or solid (teeth, broken dentures, food)—in the pharynx. In the supine position, secretions usually are cleared under direct vision using a laryngoscope and a rigid suction catheter.17 In some cases, a flexible suction catheter, introduced through the nose and nasopharynx, may be the best means of clearing the airway. A finger sweep of the pharynx may be used to detect and remove larger solid material in unconscious patients without an intact gag reflex. During all airway interventions, if cervical spine instability cannot be ruled out, relative movement of the cervical vertebrae must be prevented—most often by manual inline immobilization.17,18

Triple Airway Maneuver

The triple airway maneuver often is beneficial in obtunded patients if it is not contraindicated by concerns about cervical spine instability. As indicated by its name, this maneuver has three components: head tilt (neck extension), jaw thrust (pulling the mandible forward), and mouth opening.19 The operator stands behind and above the patient’s head. Then the maneuver is performed as follows:

• Extend the patient’s neck with the operator’s hands on both sides of the mandible.

• Elevate the mandible with the fingers of both hands, thereby lifting the base of the tongue away from the posterior pharyngeal wall.

• Open the mouth by pressing caudally on the anterior mandible with the thumbs or forefingers.

Artificial Airways

If the triple airway maneuver or any of its elements reduces airway obstruction, the benefit can be maintained for a prolonged period by introducing an artificial airway into the pharynx between the tongue and the posterior pharyngeal wall (Fig. 2.2).

The oropharyngeal airway (OPA) is the most commonly used artificial airway. Simple to insert, it is used temporarily to help facilitate oxygenation or ventilation before tracheal intubation. The OPA should be inserted with the convex side toward the tongue and then rotated through 180 degrees. Care must be taken to avoid pushing the tongue posteriorly, thereby worsening the obstruction. The nasopharyngeal airway (NPA) has the same indications as for the OPA but significantly more contraindications20 (Box 2.1). It is better tolerated than the OPA, making it useful in semiconscious patients in whom the gag reflex is partially preserved. These artificial airways should be considered to be a temporary adjunct—to be replaced with a more secure airway if the patient fails to improve rapidly to the point at which an artificial airway no longer is needed. Such airways should not be used in association with prolonged positive-pressure ventilation.

Advanced Airway Adjuncts

The laryngeal mask airway (LMA) is a small latex mask mounted on a hollow plastic tube.21–26 It is placed “blindly” in the lower pharynx overlying the glottis. The inflatable cuff helps wedge the mask in the hypopharynx, sitting obliquely over the laryngeal inlet. Although the LMA produces a seal that will allow ventilation with gentle positive pressure, it does not definitively protect the airway from aspiration. Indications for use of the LMA in critical care are (1) as an alternative to other artificial airways, (2) the difficult airway, particularly the “can’t intubate–can’t ventilate” scenario, and (3) as a conduit for bronchoscopy. It is possible to pass a 6.0-mm ET through a standard LMA into the trachea, but the LMA must be left in situ. The intubating LMA (ILMA), which was developed specifically to aid intubation with a tracheal tube, has a shorter steel tube with a wider bore, a tighter curve, and a distal silicone laryngeal cuff.27–30 A bar present near the laryngeal opening is designed to lift the epiglottis anteriorly. The ILMA allows the passage of a specially designed size 8.0 ET.

The Combitube (esophageal-tracheal double-lumen airway) is a combined esophageal obturator and tracheal tube, usually inserted blindly.31–35 Whether the “tracheal” lumen is placed in the trachea or esophagus, the Combitube will allow ventilation of the lungs and give partial protection against aspiration. The Combitube also is a potential adjunct in the “cannot intubate–cannot ventilate” situation. Disadvantages include the inability to suction the trachea when the device is sitting in its most common position (in the esophagus). Insertion also may cause trauma, and the Combitube is contraindicated in patients with known esophageal disease or injury or intact laryngeal reflexes and in persons who have ingested caustic substances.

Tracheal Intubation

If the foregoing interventions are not effective or are contraindicated, tracheal intubation is required. This modality will provide (1) a secure, potentially long-term airway; (2) a safe route to deliver positive-pressure ventilation if required; and (3) significant protection against pulmonary aspiration. Orotracheal intubation is the most widely used technique for clinicians practiced in direct laryngoscopy (indications and contraindications in Box 2.2). Normally, anesthesia with or without neuromuscular blockade is necessary for this procedure, which is summarized in Box 2.3.

Tracheal intubation requires lack of patient awareness (as in the unconscious state or with general anesthesia) and the abolition of protective laryngeal and pharyngeal reflexes. The drugs commonly used to achieve these states are shown in Table 2.1. Anesthesia is achieved using an intravenous induction agent, although intravenous sedatives (e.g., midazolam) theoretically may be used. Opioids often are used in conjunction with induction agents because they may reduce the cardiovascular sequelae of laryngoscopy and intubation (tachycardia and hypertension) and may contribute to the patient’s unconsciousness.

Table 2.1

Drugs Used to Facilitate Tracheal Intubation

| Drug | Dose (Intravenous) |

| Induction Agent | |

| Propofol | 1-2.5 mg/kg |

| Opioids | |

| Fentanyl | 1.0-1.5 µg/kg |

| Morphine | 0.15 mg/kg |

| Nondepolarizing Agents | |

| Atracurium | 0.4-0.5 mg/kg |

| Vecuronium | 0.1 mg/kg |

| Rocuronium | 0.45-0.6 mg/kg |

| Depolarizing Agent | |

| Succinylcholine (suxamethonium) | 1.0-1.5 mg/kg |

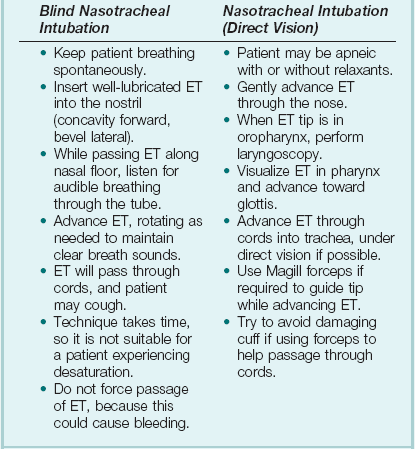

Nasotracheal intubation shares the problems and contraindications associated with the NPA.20 The technique usually is employed when there are relative contraindications to the oral route (e.g., anatomic abnormalities, cervical spine instability). Nasotracheal intubation may be achieved under direct vision or with use of a blind technique, either with the patient under general anesthesia or in the awake or lightly sedated patient with appropriate local anesthesia (Box 2.4). If orotracheal or nasotracheal intubation is required but cannot be achieved, then a surgical airway is required (see later).

With a need for isolation of one lung from another, a double-lumen tube (having one cuffed tracheal lumen and one cuffed bronchial lumen fused longitudinally) can be used.36 The main indications are (1) to facilitate some pulmonary or thoracic surgical procedures; (2) to isolate a lung containing contaminated fluid (e.g., in lung abscess) or blood, thereby preventing contralateral spread; and (3) to enable differential or independent lung ventilation (ILV). ILV allows each lung to be treated separately—for example, to deliver positive-pressure ventilation with high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) to one lung while applying low levels of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) only to the other. Such a strategy may be advantageous in cases of pulmonary air leak (bronchopleural fistula, bronchial tear, or severe lung trauma) or in severe unilateral lung disease requiring ventilatory support.37,38

Providing Ventilatory Support

Bag-Valve-Mask Ventilation

Ventilation with a mask requires an (almost) airtight fit between mask and face. This is best achieved by firmly pressing the mask against the patient’s face using the thumb and index finger (C-grip) while pulling the mandible upward toward the mask with the other three fingers. The other hand is used to squeeze the reservoir bag, generating positive pressure. Excessive pressure from the C-grip on the mask may lead to backward movement of the mandible with subsequent airway obstruction, or a tilt of the mask with leakage of gas. If a proper seal is difficult to attain, placing a hand on each side of the mask and mandible is advised, with a second person manually compressing the reservoir bag (four-handed ventilation). Bag-valve-mask systems have a self-reinflating bag, which springs back after compression, thereby drawing gas in through a port with a one-way valve. It is important to have a large reservoir bag with a continuous flow of oxygen attached to this port in order to ensure a high inspired oxygen concentration.39,40 Bag-valve-mask ventilation usually is a short-term measure in urgent situations or is used in preparation for tracheal intubation.

Prolonged Ventilation Using a Sealed Tube in the Trachea

Ventilation of the lungs with a bag-valve-mask arrangement is difficult if required for more than a few minutes or if the patient needs to be transported. In these instances, ventilation through a sealed tube in the trachea is indicated. Orotracheal or nasotracheal intubation, surgical cricothyrotomy, and tracheostomy all achieve the same result: a cuffed tube in the trachea, allowing the use of positive-pressure ventilation and protecting the lungs from aspiration. Mechanical ventilation is discussed in Chapter 9.

Apneic Oxygenation

Apneic oxygenation is achieved using a narrow catheter that sits in the trachea and carries a flow of 100% oxygen. The catheter may be passed into the trachea via an ET or under direct vision through the larynx. This apparatus can be set up as a low-flow open system (gas flow rate of 5 to 8 L per minute) or as a high-pressure (jet ventilation) system41 and can be used to maintain oxygenation with a difficult airway either at intubation or at extubation (see later).

Physiologic Sequelae and Complications of Tracheal Intubation

Laryngoscopy and intubation cause an increase in circulating catecholamines and increased sympathetic nervous system activity, leading to hypertension and tachycardia. This represents an increase in myocardial work and myocardial oxygen demand, which may provoke cardiac dysrhythmias and myocardial hypoxia or ischemia. Laryngoscopy increases cerebral blood flow and intracranial pressure—particularly in patients who are hypoxic or hypercarbic at the time of intubation.42 This rise in intracranial pressure will be exaggerated if cerebral venous drainage is impeded by violent coughing, bucking, or breath-holding.

Coughing and laryngospasm occur frequently in patients undergoing laryngoscopy and intubation when muscle relaxation and anesthesia are inadequate. Increased bronchial smooth muscle tone, which increases airway resistance, may occur as a reflex response to laryngoscopy or may be due to the physical presence of the ET in the trachea; in its most severe form, termed bronchospasm, this increased tone causes audible wheeze and ventilatory difficulty. Increased resistance to gas flow will occur because the cross-sectional area of the ET is less than that of the airway. This difference usually is unimportant with positive-pressure ventilation but causes a significant increase in work of breathing in spontaneously breathing patients. Resistance is directly related to 1/r4 (where r is the radius of the ET) and will be minimized by use of a large-bore ET. Gas passing through an ET, bypassing the nasal cavity, also loses the beneficial effects of warming, humidification, and the addition of traces of nitric oxide (NO).43

The effects of intubation on functional residual capacity (FRC) are complex. In patients under anesthesia, a fall in FRC is well documented. This decrease may be due to the loss of respiratory muscle tone following induction of anesthesia and the relatively unopposed effect of the elastic recoil in the lungs.43 The increased resistance to gas flow due to the presence of the ET may slow expiration, producing intrinsic PEEP (and therefore an increase in FRC) if the next inspiration begins before expiration is complete.

Laryngoscopy and intubation may cause bruising, abrasion, laceration, bleeding, or displacement or dislocation of the structures in and near the airway (e.g., lips, teeth or dental prostheses, tongue, epiglottis, vocal cords, laryngeal cartilages). Dislodged structures such as teeth or dentures may be aspirated, blocking the airway more distally. Less common complications include perforation of the airway with the potential for the development of a retropharyngeal abscess or mediastinitis. Over time, erosions due to pressure and ischemia may develop on the lips or tongue (or external nares and anterior nose in patients with a nasotracheal tube) and in the larynx or upper trachea.44 These lesions result in a breach of the mucosa with the potential for secondary infection. In the case of the lips and tongue, such lesions are (temporarily) disfiguring and painful and may inhibit attempts to talk or swallow.

The mucosa of the upper trachea (subglottic area) is subjected to the pressure of the cuff of the ET. This pressure reduces perfusion of the tracheal mucosa and, combined with the mechanical movement of the tube (from patient head movements, nursing procedures, or rhythmic flexion with action of the ventilator), tends to cause mucosal damage and increase the risk of superficial infection. These processes may lead to ulceration of the tracheal mucosa, fibrous scarring, contraction, and ultimately stenosis, which can be a life-limiting or life-threatening problem. Although irrefutable evidence is lacking, most clinicians believe that limiting the period of orotracheal or nasotracheal intubation and reducing cuff pressures may reduce the frequency of this complication.44

Any tube in the trachea has a significant effect on the mechanisms protecting the airway from aspiration and infection. The mucus escalator may be inhibited by mucosal injury and by the lack of warm humidified airflow over the respiratory epithelium.45 The disruption of normal swallowing results in the pooling of saliva and other debris in the pharynx and larynx above the upper surface of the tube’s inflatable cuff, which may become the source of respiratory infection if the secretions become colonized with microorganisms, or may pass beyond the cuff into the lower airways—that is, pulmonary aspiration (silent or overt).46,47 The former may occur as a result of (1) colonization of the gastric secretions and the regurgitation of this material up the esophagus to the pharynx or (2) transmission of microorganisms from the health care environment to the pharynx via medical equipment or the hands of hospital staff or visitors (cross-infection).45,47–50

The presence of a tube traversing the larynx and sealing the trachea makes phonation impossible. The implications of this limitation for patients and their families often are ignored. If patients cannot tell caregivers about pain, nausea, or other concerns, they may become frustrated, agitated, or violent. This may result in the excessive use of sedative or psychoactive drugs, which prolong time on ventilation and stay in the intensive care unit (ICU), with the risk of infection increased accordingly.51 The inability to communicate may therefore be a real threat to patient survival. Potential solutions involve the use of letter and picture boards, “speaking valves” (with tracheostomy), laryngeal microphones, or computer-based communication packages. The involvement and innovations of disciplines such as the speech and language center may be advantageous.

The Difficult Airway

The difficult airway has been defined as “the clinical situation in which a conventionally trained anesthetist experiences difficulty with mask ventilation of the upper airway, tracheal intubation, or both.”52 It has been a commonly documented cause of adverse events including airway injury, hypoxic brain injury, and death under anesthesia.53–59 The frequency of difficulty with mask ventilation has been estimated to be between 1.4% and 7.8%,60–62 while tracheal intubation using direct laryngoscopy is difficult in 1.5% to 8.5% and impossible in up to 0.5% of general anesthetics.58,63 The incidence of failed intubation is approximately 1 : 2000 in the nonobstetric population and 1 : 300 in the obstetric population.64 In the critical care unit, up to 20% of all critical incidents are airway related,65–67 and such incidents may occur at intubation, at extubation, or during the course of treatment (as with the acutely displaced or obstructed ET or tracheostomy tube).

Recognizing the Potentially Difficult Airway

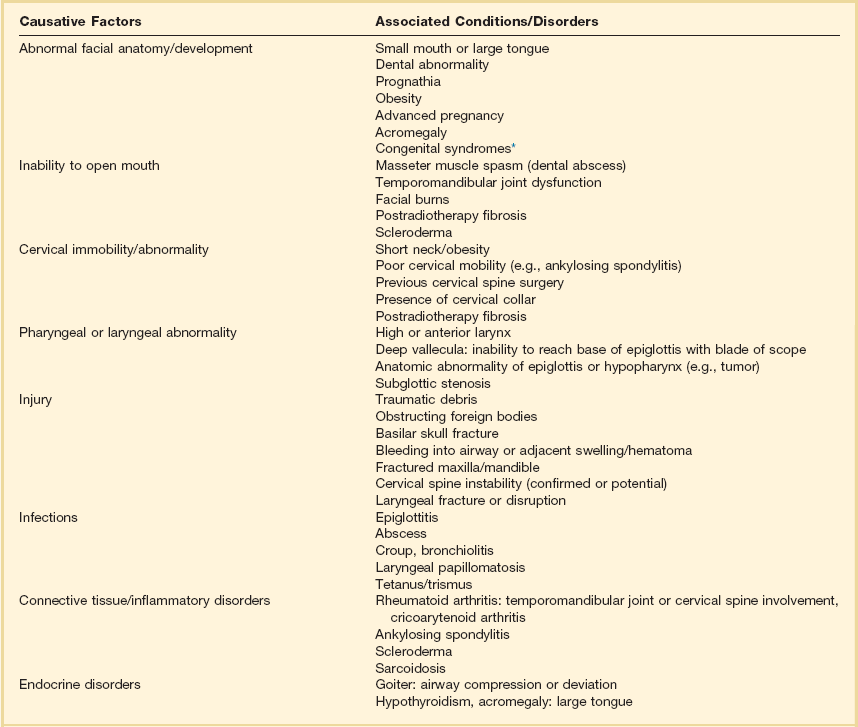

Many conditions are associated with airway difficulty (Table 2.2), including anatomic abnormalities, which may result in an unusual appearance, thereby alerting the examiner. The goal is to identify the potentially difficult airway and develop a plan to secure it. Factors including age older than 55 years, body mass index greater than 26 kg/m2, presence of a beard, lack of teeth, and a history of snoring have been identified as independent variables predicting difficulty with mask ventilation—in turn associated with difficult tracheal intubation.61,68

Table 2.2

Conditions Associated with Difficult Airway

*Visit http://www.erlanger.org/craniofacial and http://www.faces-cranio.org for specific details.

Data from Criswell JC, Parr MJA, Nolan JP: Emergency airway management in patients with cervical spine injuries. Anaesthesia 1994;49:900-903; and Morikawa S, Safar P, DeCarlo J: Influence of head position upon upper airway patency. Anaesthesiology 1961;22:265.

Mallampati69 developed a grading system (subsequently modified64) that predicted ease of tracheal intubation at direct laryngoscopy. The predictive value of the Mallampati system has been shown to be limited70,71 because many factors that have no influence on the Mallampati classification—mobility of head and neck, mandibular or maxillary development, dentition, compliance of neck structures, and body shape—can influence laryngeal view.53,66,72,73 A study of a complex system including some of these factors found the rate of difficult intubation to be 1.5%, but with a false-positive rate of 12%.74 A risk index based on the Mallampati classification, a history of difficult intubation, and five other variables lacked sufficient sensitivity and specificity.75 Airway management should be based on the fact that the difficult airway cannot be reliably predicted.76,77 This is a particularly important consideration in the critical care environment.

The Obstructed Airway

Although the most common reason for an obstructed airway in the unintubated patient is posterior displacement of the tongue in association with a depressed level of consciousness, it is the less common causes that provide the greatest challenges. It is important to elucidate the level at which the obstruction occurs and the nature of the obstructing lesion. Obstruction may be due to infection or edema (epiglottitis, pharyngeal or tonsillar abscess, mediastinal abscess), neoplasm (primary malignant or benign tumor, metastastic spread, direct extension from nearby structures), thyroid enlargement, vascular lesions, trauma, or foreign body or impacted food.14,78

Airway lesions above the level of the vocal cords are considered to lie in the upper airway and commonly manifest with stridor.79 If breathing is labored and associated with difficulty breathing at night, rather than just noisy breathing, then the narrowing probably is more than 50%. Patients with these lesions usually fall into one of two groups: (1) those who can be intubated, usually under inhalational induction, with the ENT (ear-nose-throat) surgeon immediately available to perform rigid bronchoscopy or tracheostomy if required, or (2) those who require a tracheostomy performed while under local anesthesia. In patients with midtracheal obstruction, computed tomography (CT) imaging usually is necessary to discover the exact level and nature of the obstruction and to allow planning of airway management for nonemergency clinical presentations.79 Tracheostomy often is not beneficial because the tube may not be long enough to bypass the obstruction. In such instances, fiberoptic intubation often may be useful.79 Lower tracheal obstruction often is due to space-occupying lesions in the mediastinum and necessitates multidisciplinary planning involving ENT, cardiothoracic surgery, anesthesia, and critical care team members.

Trauma and the Airway

Airway management in the trauma victim provides additional challenges because the victim often has other life-threatening conditions and preparation time for management of the difficult airway is limited. Approximately 15% of severely injured patients have maxillofacial involvement, and 5% to 10% of patients with blunt trauma have an associated cervical spine injury (often associated with head injury).80

Problems encountered in trauma patients include presence in the airway of debris or foreign bodies (e.g., teeth), vomitus, or regurgitated gastric contents; airway edema; tongue swelling; blood and bleeding; and fractures (maxilla and mandible). Patients must be assumed to have a full stomach (requiring bimanual cricoid pressure and a rapid-sequence induction for intubation), and many will have pulmonary aspiration before the airway is secured. An important consideration in most cases is the need to avoid movement of the cervical spine at laryngoscopy or intubation.17,18 Direct injury to the larynx is rare but may result in laryngeal disruption, producing progressive hoarseness and subcutaneous emphysema. Tracheal intubation, if attempted, requires great care and skill because it may cause further laryngeal disruption. With Le Fort fractures, airway obstruction or compromised respiration requiring immediate airway control is present in 25% of cases.81 Postoperative bleeding after operations to the neck (thyroid gland, carotid, larynx) may compress or displace the airway, leading to difficulty in intubation.

The Airway Practitioner and the Clinical Setting

Although airway difficulties often are due to anatomic factors as discussed, it is important to recognize that the inability to perform an airway maneuver also may be due to a practitioner’s inexperience or lack of skill.82–87 Expert opinion and clinical evidence also identify lack of skilled assistance as a factor in airway-related adverse events.88–91 As might be expected, inexperience and lack of suitable help may contribute to failure in optimizing the conditions for laryngoscopy (Box 2.5). Airway and ventilatory management performed in the prehospital setting or in the hospital but outside an operating room (OR) carries a higher frequency of adverse events and a higher mortality rate when compared with those performed using anesthesia in an OR.92–96 In the critical care unit, all invasive airway maneuvers are potentially difficult.97 Positioning is more difficult on an ICU bed than on an OR table. The airway structures may be edematous after previous laryngoscopy or presence of an ET. Neck immobility, or the need to avoid movement in a potentially unstable cervical spine, may be other contributing factors.98–100 Poor gas exchange in ICU patients reduces the effectiveness of preoxygenation and increases the risk of significant hypoxia before the airway is secured.101 Cardiovascular instability may produce hypotension or hypoperfusion, or may lead to misleading oximetry readings (including failure to record any value at all), a further confounding factor for the attending staff.102,103

Managing the Difficult Airway

Requirements for clinicians involved in airway management include the following:

• Expertise in recognition and assessment of the potentially difficult airway. This involves the use of the assessment techniques noted previously and a “sixth sense.”76

• The ability to formulate a plan (with alternatives).52,53,104–106

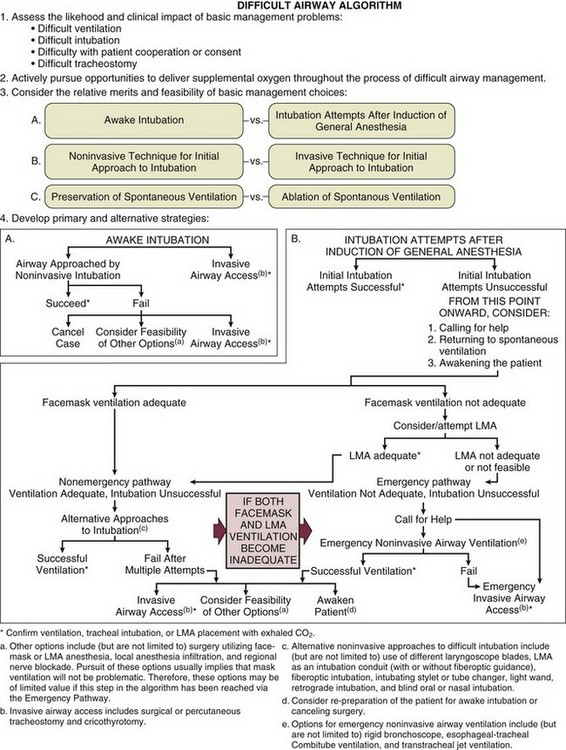

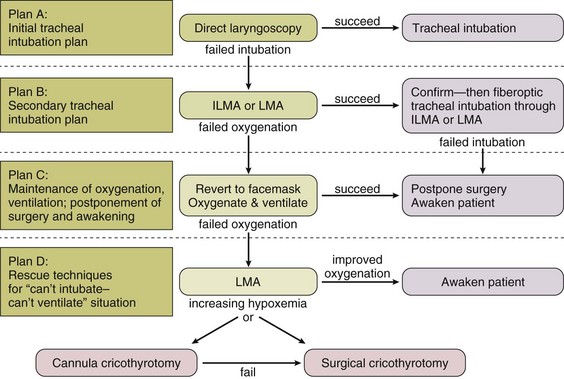

• Familiarity with algorithm(s) that outline a sequence of actions designed to maintain oxygenation, ventilation, and patient safety. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) guidelines52 and the composite plan from the Difficult Airway Society (DAS)104 are shown in Figures 2.3 and 2.4. The latter summarizes four airway plans (A to D), available from the DAS website (www.das.uk.com).

• The skills and experience to use a number of airway adjuncts, particularly those relevant to the unanticipated difficult airway.

The Anticipated Difficult Airway

Awake Intubation

Fiberoptic Intubation.

Fiberoptic intubation is a technique in which a flexible endoscope with a tracheal tube loaded along its length is passed through the glottis. The tracheal tube is then pushed off the endoscope and into the trachea, and the endoscope is withdrawn. An informed patient, trained assistance, and adequate preparation time make fiberoptic intubation less stressful. The nasotracheal route is used most often and requires the use of nasal vasoconstrictors. Nebulized local anesthetic is delivered to the airway via facemask. Sedation may be given, but ideally the patient should remain breathing spontaneously and responsive to verbal commands. The procedure often is time-consuming and tends to be used in elective situations107 (Box 2.6).

Retrograde Intubation.

For retrograde intubation,108,109 local anesthesia is provided and the cricothyroid membrane is punctured by a needle through which a wire or catheter is passed upward through the vocal cords. When it reaches the pharynx, the wire is visualized, brought out through the mouth, and then used to guide the ET through the vocal cords before it is withdrawn. This technique also can be used to guide a fiberoptic scope through the vocal cords. Owing to time constraints, it is not suitable for emergency airway access and is contraindicated in any patient with an expanding neck hematoma or coagulopathy.

Intubation Under Anesthesia

It may be decided, in spite of the safety advantage of awake intubation, to anesthetize the patient before attempted intubation. Preparation of the patient, equipment, and staff is paramount (Box 2.7). Adjuncts such as those described later should be available, either to improve the chances of intubation or to provide a safe alternative airway if intubation cannot be achieved.

Unanticipated Airway Difficulty

Bimanual Laryngoscopy

Application of pressure on the cricoid area or the upper anterior tracheal wall, or both, by the laryngoscopist (a technique sometimes termed bimanual laryngoscopy) may improve laryngeal view.110,111 When the view is optimized, an assistant maintains the pressure and thus the position of the larynx, freeing the hand of the laryngoscopist to perform the intubation. The use of “blind” cricoid pressure, or BURP (backward, upward, and rightward pressure), by an assistant may impair laryngeal visualization.112–114

Stylet (“Introducer”) and Gum Elastic Bougie

The stylet is a smooth, malleable metal or plastic rod that is placed inside an ET to adjust the curvature—typically into a J or hockey-stick shape to allow the tip of the ET to be directed through a poorly visualized or unseen glottis.115 The stylet must not project beyond the end of the ET, to avoid potential laceration or perforation of the airway.

The gum elastic bougie is a blunt-ended, malleable rod which at direct laryngoscopy may be passed through the poorly or nonvisualized larynx by putting a J-shaped bend at the tip and passing it blind in the midline upward beyond the base of the epiglottis. Then, keeping the laryngoscope in the same position in the pharynx, the ET can be “railroaded” over the bougie, which is then withdrawn. For many critical care practitioners, it is the first-choice adjunct in the difficult intubation situation.111,116

Different Laryngoscope or Blade

Greater than 50 types of curved and straight laryngoscope blades are available, the most commonly used being the curved Macintosh blade.20 Using specific blades in certain circumstances has been both encouraged117–119 and discouraged.120 In patients with a large lower jaw or “deep pharynx,” the view at laryngoscopy is often improved significantly, by using a size 4 Macintosh blade (rather than the more common adult size 3). This ensures the tip of the blade can reach the base of the vallecula to lift the epiglottis. Other blades, such as the McCoy, may be advantageous in specific situations.121,122

Lighted Stylet

A lighted stylet (light wand) is a malleable fiberoptic light source that can be passed along the lumen of an ET to facilitate blind intubation by transillumination. It allows the tracheal lumen to be distinguished from the (more posterior) esophagus on the basis of the greater intensity of light visible through anterior soft tissues of the neck as the ET passes beyond the vocal cords.123 In elective anesthesia, the intubation time and failure rate with light wand–assisted intubation were similar to those with direct laryngoscopy,124 and in a large North American survey, the light wand was the preferred alternative airway device in the difficult intubation scenario.125 A potential disadvantage is the need for low ambient light, which may not be desirable (or easily achieved) in a critical care setting.

Video Laryngoscopy

Depending upon the manufacturer, the devices vary in design; the blades can be standard Macintosh or angulated. Video laryngoscopes with a standard Macintosh blade such as the Storz device are inserted into the oral cavity using the standard direct laryngoscope technique. After insertion, an image of the airway appears on screen. In comparison, insertion of a video laryngoscope with an angulated blade such as the Glidescope, requires insertion into the middle of the oral cavity without a tongue sweep. Once the blade tip is at the base of the tongue the device is rotated so the tip of the blade is directed at the epiglottis. A precurved stylette endotracheal tube is pushed through the glottis. The stylet is withdrawn as the ET reaches the vocal cords and the ET is advanced downward.126 The Pentax airway scope has a video display incorporated into the handle. The transparent blade has two channels, one for the ET and the second to facilitate suctioning.127 The McGrath laryngoscope also had a camera mounted on a blade allowing the operator to focus on the patients face and the screen simultaneously.128

In contrast, optical laryngoscopes do not have a video attachment but instead uses a lens to provide a view of the glottis not obtained with direct laryngoscopy. The Airtraq optical laryngoscope has a blade with an optical channel and a guiding channel for the ET. It permits glottic visualization in a neutral head position.129

Multiple controlled and observational studies suggest that video laryngoscopy can provide superior views of the glottis compared to direct laryngoscopy.130,131 They may be particularly useful in patients with cervical instability, either by providing a better glottic view or by a reduction in upper cervical movement during intubation.132,133 However, an improved laryngeal view does not always equate to a successful intubation. Intubation time can also be prolonged with the video laryngoscope, especially in inexperienced hands.134 The role of the video laryngoscope in the known or anticipated difficult airway is unclear. A recent meta-analysis concluded that data on these devices in the patient with a difficult airway are inadequate.131 Current data do not suggest these devices should supersede standard direct laryngoscopy for routine or difficult airways. Further research in this area is needed.

Fiberoptic Intubation

The fiberoptic bronchoscope can be used in the unanticipated difficult airway if it is readily available and the operator is skilled.58,135,136 With an anesthetized patient, the technique may be more difficult. Loss of muscle tone will tend to allow the epiglottis and tongue to fall back against the pharyngeal wall. This can be counteracted by lifting the mandible.

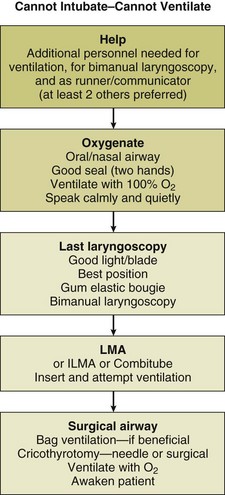

Cannot Intubate–Cannot Ventilate

“Cannot intubate–cannot ventilate” is an uncommon but life-threatening situation best managed by adherence to an appropriate algorithm.52,53,104 All personnel involved will be pressured (and motivated) by the potential for severe injury to the patient. Efficient teamwork will be more likely in an environment that is relatively calm. Although it may be difficult, shouting, impatience, anger, and panic should be avoided in such situations. Figure 2.5 presents a simple flow sheet summarizing the appropriate actions.137

Confirming Tube Position in the Trachea

A critical factor in the difficult airway scenario, potentially leading to death or brain injury, is failure to recognize misplacement of the ET. Attempted intubation of the trachea may result in esophageal intubation. This alone is not life-threatening unless it goes unrecognized.138 Thus, confirmation of ET placement in the trachea is essential.

Chest wall movement with positive-pressure ventilation (manual or mechanical) is usual but may be absent in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), obesity, or decreased compliance (e.g., in severe bronchospasm). Although condensation of water vapor in the ET suggests that the expired gas is from the lungs, this also may occur with esophageal intubation. The absence of water vapor usually is indicative of esophageal intubation. Auscultation of breath sounds (in both axillae) supports correct tube positioning but is not absolute confirmation.139 Apparent inequality of breath sounds heard in the axillae may suggest intubation of a bronchus by an ET that has passed beyond the carina. Of note, after emergency intubation and clinical confirmation of the ET in the trachea, 15% of ETs may still be inappropriately close to the carina.140

The use of capnography to detect end-tidal carbon dioxide is the most reliable objective method of confirming tube position and is increasingly available in critical care.141 False-positive results may be obtained initially when exhaled gases enter the esophagus during mask ventilation142 or when the patient is generating carbon dioxide in the gastrointestinal tract (as with recent ingestion of carbonated beverages or bicarbonate-based antacids).143 A false-negative result (ET in trachea but no carbon dioxide gas detected) may be obtained when pulmonary blood flow is minimal, as in cardiac arrest.144 Visualizing the trachea or carina through a fiberoptic bronchoscope, which may be readily available in critical care, also will confirm correct placement of the ET.

Surgical Airway

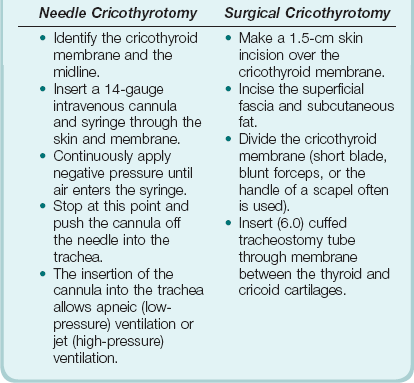

Cricothyrotomy

Cricothryotomy may be performed as a percutaneous (needle) or open surgical procedure (Box 2.8). The indication for both these techniques is the “cannot intubate–cannot ventilate” situation. Although needle cricothyrotomy is an emergency airway procedure, the technique is similar to that for “mini-tracheostomy,” which is performed electively. Unlike the other surgical airway techniques, a needle cricothyrotomy does not create a definitive airway. It will not allow excretion of carbon dioxide but will produce satisfactory oxygenation for 30 to 40 minutes. It can be viewed as a form of apneic ventilation (see later discussion). There are several methods of connecting the intravenous cannula to a gas delivery circuit with the facility to ventilate, using equipment and connections readily available in the hospital. The appropriate method thus should be thought out in advance and available on the difficult airway trolley or bag. New commercial kits that come preassembled also are available.

Tracheostomy

A tracheostomy is an opening in the trachea—usually between the second and third tracheal rings or one space higher—that may be created surgically or made percutaneously.145–149 The indications for and contraindications to tracheostomy are summarized in Box 2.9. In comparison with long-term orotracheal or nasotracheal intubation, tracheostomy often contributes to a patient who is less agitated, requires less sedation, and who may wean from ventilation more easily.51,150 This increased ability to wean is sometimes attributed to reduced anatomic dead space. The potential reduction in sedation after tracheostomy, however, is a much greater advantage to weaning than the small reduction in dead space. The benefits and complications of tracheostomy are listed in Box 2.10. Percutaneous tracheostomy is becoming increasingly common and typically is carried out by medical staff in the ICU (Box 2.11).

Another technique involving retrograde (inside-out) intubation of the trachea has been developed: A specially designed tracheal tube is used to keep the neck tissues under tension until tube placement has been accomplished.147 It is a more time-consuming technique that at present is not widely practiced.

Although no consensus exists on what defines prolonged tracheal intubation, or when tracheostomy should be performed,151 most ICUs convert the intubated airway to a tracheostomy after 1 to 3 weeks, with earlier tracheostomy becoming increasingly favored.150,151

Conventional wisdom states that the tracheostomy procedure is more complex and time-consuming than a surgical cricothyrotomy and should be performed only by a surgeon.152 Studies in the elective ICU situation suggest that cricothyrotomy is simpler and (at worst) has a similar complication rate.153,154 Although needle cricothyrotomy has long been advocated as a life-saving emergency intervention,155 recent work suggests that surgical cricothyrotomy is the more advantageous procedure.156 In patients with unfavorable anatomy, surgical cricothyrotomy is a viable alternative to elective tracheostomy.153 Surgical cricothyrotomy has been viewed as a temporary airway that should be converted to tracheostomy within a few days, but it may be used successfully as a definitive (medium-term) airway,157,158 thereby avoiding conversion from cricothyrotomy to tracheostomy, which can cause significant morbidity.159,160

Extubation in the Difficult Airway Patient (Decannulation)

The patient with a difficult airway still poses a problem at extubation, because reintubation (if required) may be even more difficult than the original procedure. Between 4% and 12% of surgical ICU patients require reintubation161 and may be hypoxic, distressed, and uncooperative at the time of reintubation. The presence of multiple risk factors for difficult intubation,100 as well as acute factors such as airway edema and pharyngeal blood and secretions, makes reestablishing the airway in such patients challenging. Before extubation of any critical care patient, the critical care team should have formulated a strategy that includes a plan for reintubation.

Stylets (airway exchange catheters) that allow gas exchange either by jet ventilation or by insufflation of oxygen may be useful in extubating the difficult airway patient.53,162,163 The stylet is placed through the ET, with care taken to ensure that the distal end has not reached as far as the carina. The ET can then be removed after a successful leak test. The stylet may remain in situ until the situation is judged to be stable.100

Tube Displacement in the Critical Care Unit

Endotracheal Tube

ET displacement in the ICU is a life-threatening emergency that may result in significant morbidity.164 Although tube dislodgement sometimes is viewed as unavoidable, often preventable factors are involved.165–167 Changes in patient posture or head position cause significant movement of the tube within the trachea.168,169 The frequency of tube displacement can be reduced by good medical and nursing practice,170 attention to the arrangements and ergonomics around the bed, achieving appropriate sedation levels, and ensuring adequate ICU nurse staffing.171,172 Experience and the ability to anticipate possible glitches constitute an important part of prevention. The management of ET displacement starts with an assessment of whether the patient can manage without the ET.167 If replacement is required, preparations for a potentially difficult reintubation are indicated.

Tracheostomy Tube

Adverse events with tracheostomy tubes are quite common.167,173 Displacement may be a life-threatening event,174 especially if the tube has been in place less than 5 to 7 days151 (before a well-defined tract between skin and trachea is formed) or if the procedure has been performed percutaneously (so that the external opening of the tract may not easily admit a new tube of the same size). The option to leave the patient without a tube should be considered, and if this option is pursued, the tracheostomy opening should be dressed to make it (to some degree) “airtight”—thus facilitating effective coughing. If the patient needs a tube but replacing the tracheostomy is not possible, then oral reintubation should be performed, after which the tracheostomy should be dressed. With a more mature tracheostomy (more than 7 days old), it usually is possible to insert a new tube through the mature tract between skin and trachea.151

The NAP4 Project

The Royal College of Anaesthetists (UK) national audit project (NAP4) provided significant insight into contemporary airway management.175 The project, using a 2-week national sample, estimated that approximately 2.9 million general anesthetics are administered in the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS) each year. Airway management involved a supraglottic airway device (SAD) in 56% of cases, a tracheal tube in 38%, and a facemask in 5%.

Failure to plan (ahead) appeared to be a common causative factor in a large number of poor airway outcomes. This was sometimes due to (1) poor assessment (no recognition that there was a potential problem needing a plan), (2) failure to plan even when potential problems were recognized, and (3) failure to have alternative plan(s) (in the event that “Plan A” was not successful). Many poor outcomes are the result of repeated use of an approach that has already (sometimes repeatedly) failed.176,177

NAP4 revealed a number of scenarios or patient-related factors that seemed to predispose to poor airway outcomes. These predictors are summarized in Box 2.12.

References

1. Finucane, BT, Santora, AH. Anatomy of the airway. In: Finucane BT, Santora AH, eds. Principles of Airway Management. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby–Year Book; 1996:1–18.

2. Standring S, ed. Gray’s Anatomy. The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice, 39th ed, London: Churchill-Livingstone, 2004.

3. Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. Cleveland, Ohio http://metrohealthanesthesia.com/edu/airway/anatomy1.htm.

4. University of Virginia Health System. http://www.healthsystem.virginia.edu/Internet/Anesthesiology-Elective/airway/anatomy.cfm

5. Institute of Rehabilitation Research and Development. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada http://www.irrd.ca/education/presentation.asp?refname22.

6. Intellimed International Corporation. http://www.innerbody.com/anim/mouth.html

7. Intellimed International Corporation. http://www.innerbody.com/image/cardov.html

8. Cowan, MJ, Gladwin, MT, Shelhamer, JH. Disorders of ciliary motility. Am J Med Sci. 2001; 321:3–10.

9. . http://www.aafp.org/afp/991115ap/2289.html

10. Byron J, Bailey JB, eds. Head and Neck Surgery—Otolaryngology. 3rd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 1993:485–491.

11. Hinds, CJ, Watson, D. Applied cardiovascular and respiratory physiology. In: Hinds CJ, Watson D, eds. Intensive Care. A Concise Textbook. 2nd ed. London: WB Saunders; 1996:19–39.

12. Sassoon, CSH, McGovern, GP. Oxygenation strategy. In: Shoemaker WC, Ayres SM, Grenvik A, Holbrook PR, eds. Textbook of Critical Care. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1999:1308–1323.

13. Burchardi, H, Richter, DW. Control of breathing. In: Webb AR, Shapiro MJ, Singer M, Suter PM, eds. Oxford Textbook of Critical Care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999:45–47.

14. Hinds, CJ, Watson, D. Respiratory failure. In: Hinds CJ, Watson D, eds. Intensive Care. A Concise Textbook. 2nd ed. London: WB Saunders; 1996:125–159.

15. Civetta JM, Taylor RW, Kirby RR, eds. Critical Care. 3rd ed. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, 1997:760.

16. Stone, DJ, Gal, TJ, Airway management. Anesthesia. 5th ed. Miller, RD, eds. Anesthesia; vol 1. Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia, 2000.

17. Watson, D. ABC of major trauma. Management of the upper airway. BMJ. 1990; 300:1388–1391.

18. Criswell, JC, Parr, MJA, Nolan, JP. Emergency airway management in patients with cervical spine injuries. Anaesthesia. 1994; 49:900–903.

19. Morikawa, S, Safar, P, DeCarlo, J. Influence of head position upon upper airway patency. Anaesthesiology. 1961; 22:265.

20. Castello, DA, Smith, HS, Lumb, PD. Conventional airway access. In: Shoemaker WC, Ayres SM, Grenvik A, Holbrook PR, eds. Textbook of Critical Care. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1999:1232–1246.

21. Brain, AI. The development of the laryngeal mask—A brief history of the invention, early clinical studies and experimental work from which the laryngeal mask evolved. Eur J Anaesthesiol Suppl. 1991; 4:5–17.

22. Maltby, JR, Loken, RG, Watson, NC. The laryngeal mask airway: Clinical appraisal in 250 patients. Can J Anaesth. 1990; 37:509–513.

23. Pennant, JH, White, PF. The laryngeal mask airway. Its uses in anesthesiology. Anesthesiology. 1993; 79:144.

24. Ramachandran, K, Kannan, S. Laryngeal mask airway and the difficult airway. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2004; 17:491–493.

25. Ezri, T, Szmuk, P, Warters, RD, et al. Difficult airway management practice patterns among anesthesiologists practicing in the United States: Have we made any progress? J Clin Anesth. 2003; 15:418–422.

26. Parmet, JL, Colonna-Romano, P, Horrow, JC, et al. The laryngeal mask airway reliably provides rescue ventilation in cases of unanticipated difficult tracheal intubation along with difficult mask ventilation. Anesth Analg. 1998; 87:661–665.

27. Brain, AI, Verghese, C, Addy, EV, et al. The intubating laryngeal mask. II: A preliminary clinical report of a new means of intubating the trachea. Br J Anaesth. 1997; 79:699.

28. Joo, HS, Kapoor, S, Rose, DK, et al. The intubating laryngeal mask airway after induction of general anesthesia versus awake fiberoptic intubation in patients with difficult airways. Anesth Analg. 2001; 92:1342–1346.

29. Combes, X, Sauvat, S, Leroux, B, et al. Intubating laryngeal mask airway in morbidly obese and lean patients: A comparative study. Anesthesiology. 2005; 102:1106–1109.

30. Combes, X, Le Roux, B, Suen, P, et al. Unanticipated difficult airway in anesthetized patients: Prospective validation of a management algorithm. Anesthesiology. 2004; 100:1146–1150.

31. Lavery, GG, McCloskey, B. Airway management. In: Patient Centered Acute Care Training (PACT) 2011. Brussels: European Society of Intensive Care Medicine; 2011.

32. Krafft, P, Schebesta, K. Alternative management techniques for the difficult airway: Esophageal-tracheal Combitube. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2004; 17:499–504.

33. Rabitsch, W, Schellongowski, P, Staudinger, T, et al. Comparison of a conventional tracheal airway with the Combitube in an urban emergency medical services system run by physicians. Resuscitation. 2003; 57:27–32.

34. Mort, TC. Laryngeal mask airway and bougie intubation failures: The Combitube as a secondary rescue device for in-hospital emergency airway management. Anesth Analg. 2006; 103:1264–1266.

35. Rumball, CJ, MacDonald, D. The PTL, Combitube, laryngeal mask, and oral airway: A randomized prehospital comparative study of ventilatory device effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in 470 cases of cardiorespiratory arrest. Prehosp Emerg Care. 1997; 1:1–10.

36. Campos, JH. Which device should be considered the best for lung isolation: Double-lumen endotracheal tube versus bronchial blockers? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2007; 20:27–31.

37. Wendt, M, Hachenberg, T, Winde, G, Lawin, P. Differential ventilation with low-flow CPAP and CPPV in the treatment of unilateral chest trauma. Intensive Care Med. 1989; 15:209–211.

38. Cheatham, ML, Promes, JT. Independent lung ventilation in the management of traumatic bronchopleural fistula. Am Surg. 2006; 72:530–533.

39. Bateman, NT, Leach, RM. ABC of oxygen. Acute oxygen therapy. BMJ. 1998; 317:798.

40. Campbell, TP, Stewart, RD, Kaplan, RM, et al. Oxygen enrichment of bag-valve-mask units during positive-pressure ventilation: A comparison of various techniques. Ann Emerg Med. 1988; 17:22–25.

41. Hartmannsgruber, MW, Loudermilk, E, Stoltzfus, D. Prolonged use of a Cook airway exchange catheter obviated the need for postoperative tracheostomy in an adult patient. J Clin Anesth. 1997; 9:496–498.

42. Turner, BK, Wakim, JH, Secrest, J, et al. Neuroprotective effects of thiopental, propofol, and etomidate. AANA J. 2005; 73:297–302.

43. Hedenstierna, G. Physiology of the intubated airway. In: Webb AR, Shapiro MJ, Singer M, Suter PM, eds. Oxford Textbook of Critical Care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999:1293–1295.

44. Hinds, CJ, Watson, D. Respiratory support. In: Hinds CJ, Watson D, eds. Intensive Care. A Concise Textbook. 2nd ed. London: WB Saunders; 1996:161–192.

45. Levine, SA, Niederman, MS. The impact of tracheal intubation on host defenses and risks for nosocomial pneumonia. Clin Chest Med. 1991; 12:523–543.

46. Fleming, CA, Balaguera, HU, Craven, DE. Risk factors for nosocomial pneumonia. Focus on prophylaxis. Med Clin North Am. 2001; 85:1545–1563.

47. Craven, DE. Preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults: Sowing seeds of change. Chest. 2006; 130:251–260.

48. Safdar, N, Crnich, CJ, Maki, DG. The pathogenesis of ventilator-associated pneumonia: Its relevance to developing effective strategies for prevention. Respir Care. 2003; 50:725–739.

49. Crnich, CJ, Safdar, N, Maki, DG. The role of the intensive care unit environment in the pathogenesis and prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Respir Care. 2005; 50:813–836.

50. Lorente, L, Lecuona, M, Jimenez, A, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia using a heated humidifier or a heat and moisture exchanger: A randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2006; 10:R116.

51. Lavery, GG. Optimum sedation and analgesia in critical illness: We need to keep trying. Crit Care. 2004; 8:433–434.

52. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2003; 98:1269–1277.

53. Benumof, JL. Management of the difficult adult airway. With special emphasis on awake tracheal intubation. Anesthesiology. 1991; 75:1087–1110.

54. Rashkin, MC, Davis, T. Acute complications of endotracheal intubation. Chest. 1986; 89:165–167.

55. Caplan, RA, Posner, KL, Ward, RJ, et al. Adverse respiratory events in anaesthesia: A closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 1990; 72:828–833.

56. Rose, DK, Cohen, MM. The airway: problems and predictions in 18,500 patients. Can J Anaesth. 1994; 41:372–383.

57. Peterson, GN, Domino, KB, Caplan, RA, et al. Management of the difficult airway: A closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 2005; 103:33–39.

58. Burkle, CM, Walsh, MT, Harrison, BA, et al. Airway management after failure to intubate by direct laryngoscopy: Outcomes in a large teaching hospital. Can J Anaesth. 2005; 52:634–640.

59. Domino, KB, Posner, KL, Caplan, RA, et al. Airway injury during anesthesia: A closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 1999; 91:1703–1711.

60. Kheterpal, S, Han, R, Tremper, KK, et al. Incidence and predictors of difficult and impossible mask ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2006; 105:885–891.

61. Langeron, O, Masso, E, Huraux, C, et al. Prediction of difficult mask ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2000; 92:1229.

62. Yildiz, TS, Solak, M, Toker, K. The incidence and risk factors of difficult mask ventilation. J Anesth. 2005; 19:7–11.

63. Crosby, ET, Cooper, RM, Douglas, MJ, et al. The unanticipated difficult airway with recommendations for management. Can J Anaesth. 1998; 45:757–776.

64. Samsoon, GLT, Young, JRB. Difficult tracheal intubation: A retrospective study. Anaesthesia. 1987; 42:487.

65. Needham, DM, Thompson, DA, Holzmueller, CG, et al. A system factors analysis of airway events from the Intensive Care Unit Safety Reporting System (ICUSRS). Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:2227–2233.

66. Beckmann, U, Baldwin, I, Hart, GK, et al. The Australian Incident Monitoring Study in Intensive Care: AIMS-ICU. An analysis of the first year of reporting. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1996; 24:320–329.

67. Beckmann, U, Baldwin, I, Durie, M, et al. Problems associated with nursing staff shortage: An analysis of the first 3600 incident reports submitted to the Australian Incident Monitoring Study (AIMS-ICU). Anaesth Intensive Care. 1998; 26:396–400.

68. Ezri, T, Weisenberg, M, Khazin, V, et al. Difficult laryngoscopy: Incidence and predictors in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery versus general surgery patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2003; 17:321–324.

69. Mallampati, SR, Gatt, SP, Gugino, LD, et al. A clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation: A prospective study. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1985; 32:429.

70. Cattano, D, Panicucci, E, Paolicchi, A, et al. Risk factors assessment of the difficult airway: An Italian survey of 1956 patients. Anesth Analg. 2004; 99:1774–1779.

71. Lee, A, Fan, LT, Gin, T, et al. A systematic review (meta-analysis) of the accuracy of the Mallampati tests to predict the difficult airway. Anesth Analg. 2006; 102:1867–1878.

72. Pilkington, S, Carli, F, Dakin, MJ, et al. Increase in Mallampati score during pregnancy. Br J Anaesth. 1995; 74:638.

73. Benumof, JL. Obesity, sleep apnea, the airway and anesthesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2004; 17:21–30.

74. Wilson, ME, Spiegelhalter, D, Robertson, JA, et al. Predicting difficult intubation. Br J Anaesth. 1988; 61:211.

75. El-Ganzouri, AR, McCarthy, RJ, Tuman, KJ, et al. Preoperative airway assessment predictive value of a multivariate risk index. Anesth Analg. 1996; 82:1197.

76. Rosenblatt, WH. Preoperative planning of airway management in critical care patients. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:S186–S192.

77. Yentis, SM. Predicting difficult intubation—Worthwhile exercise or pointless ritual? Anaesthesia. 2002; 57:105–109.

78. Field, JM, Baskett, PJF. Basic airway management. In: Webb AR, Shapiro MJ, Singer M, Suter PM, eds. Oxford Textbook of Critical Care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999:1–6.

79. Mason, RA, Fielder, CP. The obstructed airway in head and neck surgery. Anaesthesia. 1999; 54:625–628.

80. Morris, CG, McCoy, EP, Lavery, GG. Spinal immobilisation for unconscious patients with multiple injuries. BMJ. 2004; 329:495–499.

81. Ardekian, L, Rosen, D, Klein, Y, et al. Life threatening complications and irreversible damage following maxillofacial trauma. Injury. 1998; 29:253–256.

82. Awad, Z, Pothier, DD. Management of surgical airway emergencies by junior ENT staff: A telephone survey. J Laryngol Otol. 2006; 1–4.

83. Rosenstock, C, Ostergaard, D, Kristensen, MS, et al. Residents lack knowledge and practical skills in handling the difficult airway. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004; 48:1014–1018.

84. Schwid, HA, Rooke, GA, Carline, J, et al. Evaluation of anesthesia residents using mannequin-based simulation: A multiinstitutional study. Anesthesiology. 2002; 97:1434–1444.

85. Sagarin, MJ, Barton, ED, Chang, YM, et al. Airway management by US and Canadian emergency medicine residents: A multicenter analysis of more than 6,000 endotracheal intubation attempts. Ann Emerg Med. 2005; 46:328–336.

86. Kluger, MT, Short, TG. Aspiration during anaesthesia: A review of 133 cases from the Australian Anaesthetic Incident Monitoring Study (AIMS). Anaesthesia. 1999; 54:19–26.

87. Mayo, PH, Hackney, JE, Mueck, JT, et al. Achieving house staff competence in emergency airway management: Results of a teaching program using a computerized patient simulator. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:2422–2427.

88. Vickers, MD. Anaesthetic team and the role of nurses—European perspective. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2002; 16:409–421.

89. James, MR, Milsom, PL. Problems encountered when administering general anaesthetics in accident and emergency departments. Arch Emerg Med. 1988; 5:151–155.

90. Kluger, MT, Bukofzer, M, Bullock, M, et al. Anaesthetic assistants: Their role in the development and resolution of anaesthetic incidents. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1999; 27:269–274.

91. Kluger, MT, Bullock, MF. Recovery room incidents: A review of 419 reports from the Anaesthetic Incident Monitoring Study (AIMS). Anaesthesia. 2002; 57:1060–1066.

92. Robbertze, R, Posner, KL, Domino, KB. Closed claims review of anesthesia for procedures outside the operating room. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2006; 19:436–442.

93. Wang, HE, Seitz, SR, Hostler, D, Yealy, DM. Defining the learning curve for paramedic student endotracheal intubation. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005; 2:156–162.

94. Wang, HE, Kupas, DF, Paris, PM, et al. Multivariate predictors of failed prehospital endotracheal intubation. Acad Emerg Med. 2003; 10:717–724.

95. Krisanda, TJ, Eitel, DR, Hess, D, et al. An analysis of invasive airway management in a suburban emergency medical services system. Prehospital Disaster Med. 1992; 7:121–126.

96. Wang, HE, Sweeney, TA, O’Connor, RE, et al. Failed prehospital intubations: An analysis of emergency department courses and outcomes. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2001; 5:134–141.

97. Schwartz, DE, Matthay, MA, Cohen, NH. Death and other complications of emergency airway management in critically ill adults. A prospective investigation of 297 tracheal intubations. Anesthesiology. 1995; 82:367–376.

98. Brimacombe, J, Keller, C, Kunzel, KH, et al. Cervical spine motion during airway management: A cinefluoroscopic study of the posteriorly destabilized third cervical vertebrae in human cadavers. Anesth Analg. 2000; 91:1274–1278.

99. Waltl, B, Melischek, M, Schuschnig, C, et al. Tracheal intubation and cervical spine excursion: Direct laryngoscopy vs. intubating laryngeal mask. Anaesthesia. 2001; 56:221–226.

100. Loudermilk, EP, Hartmannsgruber, M, Stoltzfus, DP, et al. A prospective study of the safety of tracheal extubation using a pediatric airway exchange catheter for patients with a known difficult airway. Chest. 1997; 111:1660–1665.

101. Mort, TC. Preoxygenation in critically ill patients requiring emergency tracheal intubation. Crit Care Med. 2005; 33:2672–2675.

102. Jensen, LA, Onyskiw, JE, Prasad, NG. Meta-analysis of arterial oxygen saturation monitoring by pulse oximetry in adults. Heart Lung. 1998; 27:387–408.

103. Van de Louw, A, Cracco, C, Cerf, C, et al. Accuracy of pulse oximetry in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2001; 27:1606–1613.

104. Henderson, JJ, Popat, MT, Latto, IP, et al. Difficult Airway Society guidelines for management of the unanticipated difficult intubation. Anaesthesia. 2004; 59:675–694.

105. Benumof, JL. Laryngeal mask airway and the ASA difficult airway algorithm. Anaesthesiology. 1996; 84:686–699.

106. Heidegger, T, Gerig, HJ. Algorithms for management of the difficult airway. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2004; 17:483–484.

107. Cobley, M, Vaughan, RS. Recognition and management of difficult airway problems. Br J Anaesth. 1992; 68:90–97.

108. Gupta, B, McDonald, JS, Brooks, JH, et al. Oral fiberoptic intubation over a retrograde guidewire. Anesth Analg. 1989; 68:517–519.

109. Finucane, BT, Santora, AH. Fibreoptic intubation in airway management. In: Finucane BT, Santora AH, eds. Principles of Airway Management. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby–Year Book; 1996:102.

110. Levitan, RM, Mickler, T, Hollander, JE. Bimanual laryngoscopy: A videographic study of external laryngeal manipulation by novice intubators. Ann Emerg Med. 2002; 40:30–37.

111. Latto, IP, Stacey, M, Mecklenburgh, J, et al. Survey of the use of the gum elastic bougie in clinical practice. Anaesthesia. 2002; 57:379–384.

112. Yentis, SM. The effects of single-handed and bimanual cricoid pressure on the view at laryngoscopy. Anaesthesia. 1997; 52:332–335.

113. Snider, DD, Clarke, D, Finucane, BT. The “BURP” maneuver worsens the glottic view when applied in combination with cricoid pressure. Can J Anaesth. 2005; 52:100–104.

114. Levitan, RM, Kinkle, WC, Levin, WJ, et al. Laryngeal view during laryngoscopy: A randomized trial comparing cricoid pressure, backward-upward-rightward pressure, and bimanual laryngoscopy. Ann Emerg Med. 2005; 47:548–555.

115. Finucane, BT, Santora, AH. Difficult intubation. In: Finucane BT, Santora AH, eds. Principles of Airway Management. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby–Year Book; 1996:187–226.

116. Bokhari, A, Benham, SW, Popat, MT. Management of unanticipated difficult intubation: A survey of current practice in the Oxford region. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2004; 21:123–127.

117. MacQuarrie, K, Hung, OR, Law, JA. Tracheal intubation using Bullard laryngoscope for patients with a simulated difficult airway. Can J Anaesth. 1999; 46:760–765.

118. Yardeni, IZ, Gefen, A, Smolyarenko, V, et al. Design evaluation of commonly used rigid and levering laryngoscope blades. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002; 1003–1009.

119. McIntyre, JW. Laryngoscope design and the difficult adult tracheal intubation. Can J Anaesth. 1989; 36:94–98.

120. Sethuraman, D, Darshane, S, Guha, A, et al. A randomised, crossover study of the Dorges, McCoy and Macintosh laryngoscope blades in a simulated difficult intubation scenario. Anaesthesia. 1989; 61:482–487.

121. Cook, TM, Tuckey, JP. A comparison between the Macintosh and the McCoy laryngoscope blades. Anaesthesia. 1996; 51:977–980.

122. Chisholm, DG, Calder, I. Experience with the McCoy laryngoscope in difficult laryngoscopy. Anaesthesia. 1997; 52:906–908.

123. Mehta, S. Transtracheal illumination for optimal tracheal tube placement. A clinical study. Anaesthesia. 1989; 44:970–972.

124. Hung, OR, Pytka, S, Morris, I. Clinical trial of a new lightwand device (Trachlight) to intubate the trachea. Anesthesiology. 1995; 83:509–514.

125. Wong, DT, Lai, K, Chung, FF, et al. Cannot intubate-cannot ventilate and difficult intubation strategies: Results of a Canadian national survey. Anesth Analg. 2005; 100:1439–1446.

126. Cooper, RM, Pacey, JA, Bishop, MJ, McCluskey, SA. Early clinical experience with a new videolaryngoscope (GlideScope®) in 728 patients. Can J Anaesth. 2005; 52:191–198.

127. Asai, T, Enomoto, Y, Shimizu, K, et al. The Pentax-AWS video-laryngoscope: The first experience in one hundred patients. Anesth Analg. 2008; 106:257–259.

128. Shippey, B, Ray, D, McKeown, D. Case series: The McGrath® videolaryngoscope—An initial clinical evaluation. Can J Anesth. 2007; 54(4):307–313.

129. Lu, Y, Jiang, H, Zhu, Y. Airtraq laryngoscope versus conventional Macintosh laryngoscope: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesthesia. 2011; 66(12):1160–1167.

130. Niforopoulou, P, Pantazopoulos, I, Demestiha, T, et al. Video-laryngoscopes in the adult airway management: A topical review of the literature. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010; 54:1050–1061.

131. Mihai, R, Blair, E, Kay, H, Cook, T. A quantitative review and meta-analysis of performance of non-standard laryngoscopes and rigid fibreoptic intubation aids. Anaesthesia. 2008; 63:745–760.

132. Turkstra, T, Craen, R, Pelz, D, Gelb, A. Cervical spine motion: A fluoroscopic comparison during intubation with lighted stylet, GlideScope, and Macintosh laryngoscope. Anesth Analg. 2005; 101:910–915.

133. Robitaille, A, Williams, S, Tremblay, M, et al. Cervical spine motion during tracheal intubation with manual in-line stabilization: Direct laryngoscopy versus GlideScope videolaryngoscopy. Anesth Analg. 2008; 106:935–941.

134. Sun, D, Warriner, C, Parsons, D, et al. The GlideScope Video Laryngoscope: Randomized clinical trial in 200 patients. Br J Anaesth. 2005; 94(3):381–384.

135. Morris, IR. Continuing medical education: Fibreoptic intubation. Can J Anesth. 1994; 41:996–1008.

136. Jolliet, P, Chevrolet, JC. Bronchoscopy in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 1992; 18:160–169.

137. Lavery, GG, McCloskey, BV. The difficult airway in adult critical care. Crit Care Med. 2008; 36(7):2163–2173.

138. Schwartz, DE, Matthay, MA, Cohen, NH. Death and other complications of emergency airway management in critically ill adults. A prospective investigation of 297 tracheal intubations. Anesthesiology. 1995; 82:367–376.

139. Birmingham, PK, Cheney, FW, Ward, RJ. Esophageal intubation: A review of detection techniques. Anesth Analg. 1986; 65:886–891.

140. Schwartz, DE, Lieberman, JA, Cohen, NH. Women are at greater risk than men for malpositioning of the endotracheal tube after emergent intubation. Crit Care Med. 1994; 22:1127–1131.

141. Erasmus, PD. The use of end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring to confirm endotracheal tube placement in adult and paediatric intensive care units in Australia and New Zealand. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2004; 32:672–675.

142. Linko, K, Paloheimo, M, Tammisto, T. Capnography for detection of accidental oesophageal intubation. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1983; 27:199–202.

143. Sum Ping, ST, Mehta, MP, Symreng, T. Reliability of capnography in identifying esophageal intubation with carbonated beverage or antacid in the stomach. Anesth Analg. 1991; 73:333.

144. Falk, JL, Rackow, EC, Weil, MH. End-tidal carbon dioxide concentration during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 1988; 318:607.

145. Moe, KS, Stoeckli, SJ, Schmid, S, et al. Percutaneous tracheostomy: A comprehensive evaluation. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999; 108:384–391.

146. Powell, DM, Price, PD, Forrest, LA. Review of percutaneous tracheostomy. Laryngoscope. 1998; 108:170–177.

147. Konopke, R, Zimmermann, T, Volk, A, et al. Prospective evaluation of the retrograde percutaneous translaryngeal tracheostomy (Fantoni procedure) in a surgical intensive care unit: Technique and results of the Fantoni tracheostomy. Head Neck. 2006; 28:355–359.

148. Westphal, K, Byhahn, C, Wilke, HJ, et al. Percutaneous tracheostomy: A clinical comparison of dilatational (Ciaglia) and translaryngeal (Fantoni) techniques. Anesth Analg. 1999; 89:938–943.

149. Groves, DS, Durbin, CG, Jr. Tracheostomy in the critically ill: Indications, timing and techniques. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007; 13:90–97.

150. Schweikert, WD, Gelbach, BK, Pohlman, AJ, et al. Daily interruption of sedative infusions and complications of critical illness in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:1272–1276.

151. Hazard, PB. Tracheostomy. In: Webb AR, Shapiro MJ, Singer M, Suter PM, eds. Oxford Textbook of Critical Care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999:1305–1308.

152. Finucane, BT, Santora, AH. Surgical approaches to airway management. In: Finucane BT, Santora AH, eds. Principles of Airway Management. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby–Year Book; 1996:251–284.

153. Rehm, CG, Wanek, SM, Gagnon, EB, et al. Cricothyroidotomy for elective airway management in critically ill trauma patients with technically challenging neck anatomy. Crit Care. 2002; 6:531–535.

154. Francois, B, Clavel, M, Desachy, A, et al. Complications of tracheostomy performed in the ICU: Subthyroid tracheostomy vs surgical cricothyroidotomy. Chest. 2003; 123:151–158.