Chapter 104 Adolescent Development

See also Part XII and Chapters 555 and 556.

104.1 Adolescent Physical and Social Development

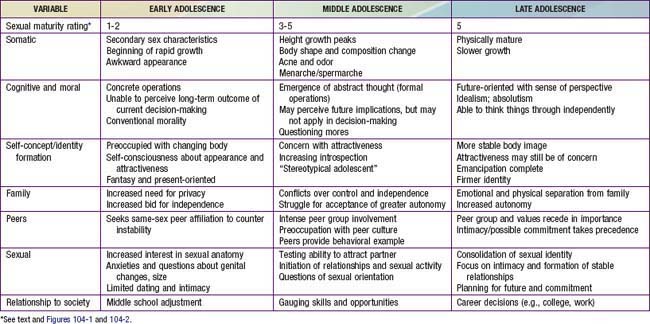

Young people undergo rapid changes in body structure and physiologic, psychological, and social functioning between the ages of approximately 9 to 10 and 20 yr. Adolescence consists of 3 distinct periods—early, middle, and late—each marked by a characteristic set of biologic, psychological, and social issues (Table 104-1). Hormones set this developmental agenda together with social structures designed to foster the transition from childhood to adulthood. Although individual variation is substantial, in both the timing of somatic changes and the quality of the experience, pubertal changes follow a predictable sequence. Gender and subculture profoundly affect the developmental course, as do physical and social stressors.

Early Adolescence

Biologic Development

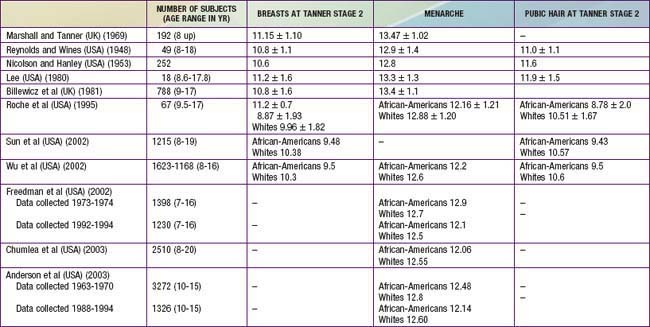

Data regarding the timing for the onset of puberty in girls are controversial (Table 104-2). Several studies from 1948 to 1981 identified the average age for the onset of breast development to range from 10.6-11.2 yr of age. Multiple reports since 1997 suggest a significantly earlier onset of breast development, ranging from 8.9-9.5 yr in African-American girls and 10.0-10.4 yr in white girls. There also appears to be a small secular trend toward decreasing ages for the onset of pubic hair development and menarche. The reasons for the larger decrease in age for breast development may include the epidemic of childhood obesity as well as exposure to estrogen-like toxins in the environment that include certain pesticides, plastics, phytoestrogens, and industrial compounds along with beef fattened with subcutaneous estrogen pellets.

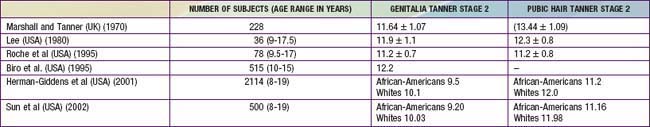

It is less clear whether there is also a secular trend for decreasing age for onset of puberty in boys (Table 104-3). It appears that, over the past 40 yr, the average age for the onset of genital and pubic hair development may have decreased by about a year. The onset of puberty in African-American boys precedes that in white boys by at least 6 mo.

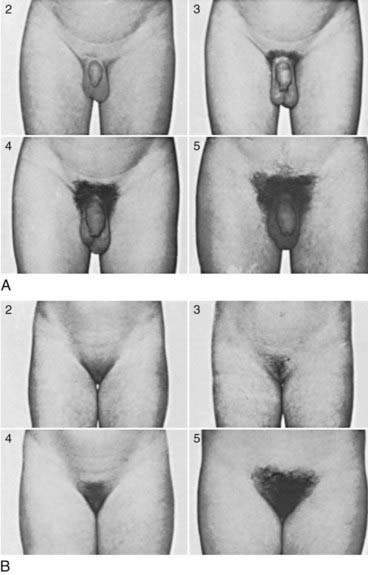

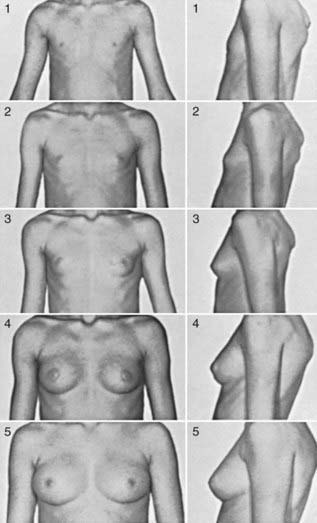

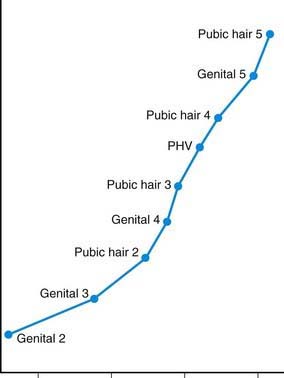

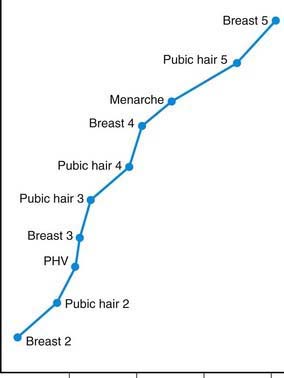

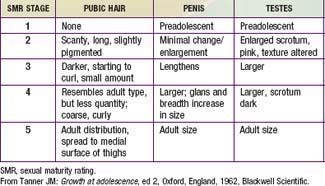

Once the onset of puberty has begun, the resulting sequence of somatic and physiologic changes gives rise to the sexual maturity rating (SMR), or Tanner stages. Figures 104-1 and 104-2 depict the somatic changes used in the SMR scale; Tables 104-4 and 104-5 also describe these changes. Figures 104-3 and 104-4 depict the typical sequence of pubertal changes in boys and girls, respectively. The range of normal progress through sexual maturation is wide.

Figure 104-1 Sexual maturity ratings (2 to 5) of pubic hair changes in adolescent boys (A) and girls (B) (see Tables 104-4 and 104-5).

(Courtesy of J.M. Tanner, MD, Institute of Child Health, Department for Growth and Development, University of London, London, England.)

Figure 104-2 Sexual maturity ratings (1 to 5) of breast changes in adolescent girls.

(Courtesy of J.M. Tanner, MD, Institute of Child Health, Department for Growth and Development, University of London, London, England.)

Table 104-4 CLASSIFICATION OF SEXUAL MATURITY STATES IN GIRLS

| SMR STAGE | PUBIC HAIR | BREASTS |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Preadolescent | Preadolescent |

| 2 | Sparse, lightly pigmented, straight, medial border of labia | Breast and papilla elevated as small mound; diameter of areola increased |

| 3 | Darker, beginning to curl, increased amount | Breast and areola enlarged, no contour separation |

| 4 | Coarse, curly, abundant, but less than in adult | Areola and papilla form secondary mound |

| 5 | Adult feminine triangle, spread to medial surface of thighs | Mature, nipple projects, areola part of general breast contour |

SMR, sexual maturity rating.

From Tanner JM: Growth at adolescence, ed 2, Oxford, England, 1962, Blackwell Scientific.

Figure 104-3 Sequence of pubertal events in males. PHV, peak height velocity.

(From Root AW: Endocrinology of puberty, J Pediatr 83:1, 1973.)

Figure 104-4 Sequence of pubertal events in females. PHV, peak height velocity.

(From Root AW: Endocrinology of puberty, J Pediatr 83:1, 1973.)

In girls, the 1st visible sign of puberty and the hallmark of SMR2 is the appearance of breast buds, between 8 and 12 yr of age. Menses typically begins 2- yr later, during SMR3-4 (median age, 12 yr; normal range, 9-16 yr) (see Fig. 104-4). Less obvious changes include enlargement of the ovaries, uterus, labia, and clitoris, and thickening of the endometrium and vaginal mucosa.

yr later, during SMR3-4 (median age, 12 yr; normal range, 9-16 yr) (see Fig. 104-4). Less obvious changes include enlargement of the ovaries, uterus, labia, and clitoris, and thickening of the endometrium and vaginal mucosa.

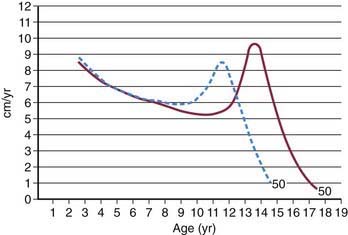

Growth acceleration begins in early adolescence for both sexes, but peak growth velocities are not reached until SMR3-4. Boys typically peak 2-3 yr later than girls, begin this growth at a later SMR stage (Fig. 104-5), and continue their linear growth for approximately 2-3 yr after girls have stopped. The asymmetric growth spurt begins distally, with enlargement of the hands and feet, followed by the arms and legs, and finally, the trunk and chest, giving young adolescents a gawky appearance. Rapid enlargement of the larynx, pharynx, and lungs leads to changes in vocal quality, typically preceded by vocal instability (voice cracking). Elongation of the optic globe often results in nearsightedness. Dental changes include jaw growth, loss of the final deciduous teeth, and eruption of the permanent cuspids, premolars, and finally, molars (Chapter 299). Orthodontic appliances may be needed, secondary to growth exacerbations of bite disturbances.

Self-Concept

This exposure may cause girls to develop a distorted sense of femininity, and they may be at risk for viewing themselves as overweight, leading to eating disorders and depression (Chapter 26). Similarly, boys may have difficulties with self-image. Images of masculinity may be confusing, leading to self-doubt, insecurity, and misleading conceptions about male behavior. Adolescents who develop earlier than their peers, especially girls, may have higher rates of school difficulty, body dissatisfaction, and depression. These adolescents look like adults and may have adult expectations placed on them, but are not cognitively or psychologically mature.

Middle Adolescence

Biologic Development

Growth accelerates above the prepubertal rate of 6-7 cm (3 in) per year during middle adolescence. In the average girl, the growth spurt peaks at 11.5 yr at a top velocity of 8.3 cm (3.8 in) per year and then slows to a stop at 16 yr (see Fig. 104-5). In the average boy, the growth spurt starts later, peaks at 13.5 yr at 9.5 cm (4.3 in) per year, and then slows to a stop at 18 yr. Weight gain parallels linear growth, with a delay of several months, so that adolescents seem first to stretch and then to fill out. Muscle mass also increases, followed approximately 6 mo later by an increase in strength; boys show greater gains in both. Lean body mass, approximately 80% in the average prepubertal child, increases to 90% in boys and decreases to 75% in girls as subcutaneous fat accumulates.

Boys with SMR3 pubic hair and SMR4 genitals normally have their peak growth spurts ahead of them; girls at the same SMR are usually past their peaks (see Figs. 104-3 and 104-4). Widening of the shoulders in boys and the hips in girls is also hormonally determined. Other changes include a doubling in heart size and lung vital capacity. Blood pressure, blood volume, and hematocrit rise, particularly in boys. Androgenic stimulation of sebaceous and apocrine glands results in acne and body odor. Physiologic changes in sleep patterns and requirements may be mistaken for laziness; adolescents have difficulty falling asleep and waking up, especially for early school start times as opposed to typical self-regulated or preferred sleep schedules.

Late Adolescence

Afifi TD, Joseph A, Aldeis D. Why can’t we just talk about it? J Adolesc Res. 2008;23:689-721.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health Care. The initial reproductive health visit. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):240-243.

Campbell IG, Feinberg I. Longitudinal trajectories of non-rapid eye movement delta and theta EEG as indicators of adolescent brain maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5177-5180.

Carey WL, Coleman WL, Elias ER, et al, editors. Developmental-behavioral pediatrics, ed 4, Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier, 2009.

Carswell JM, Stafford DEJ. Normal physical growth and development. In: Neinstein LS, Gordon CM, Katzman DK, et al, editors. Adolescent health care: a practical guide. ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:3-26.

Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, et al. Age of sexual debut among U.S. adolescents. Contraception. 2009;80:158-162.

Euling SY, Herman-Giddens ME, Lee PA, et al. Examination of U.S. puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: panel findings. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl 3):S172-S191.

Kambam P, Thompson C. The development of decision-making capacities in children and adolescents: psychological and neurological perspectives and their implications for juvenile defendants. Behav Sci Law. 2009;27:173-190.

Manlove J, Ikramullah E, Mincieli L, et al. Trends in sexual experience, contraceptive use, and teenage childbearing: 1992–2002. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:413-423.

McGrath N, Nyirenda M, Hosegood V, et al. Age at first sex in rural South Africa. Sex Trans Infect. 2009;85(Suppl 1):i49-i55.

Radzik M, Sherer S, Neinstein LS. Psychosocial development in normal adolescents. In: Neinstein LS, Gordon CM, Katzman DK, et al, editors. Adolescent health care: a practical guide. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:27-31.

Slyper AH. The pubertal timing controversy in the USA and a review of possible causative factors for the advance in the timing of onset of puberty. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2006;65:1-8.

Steinberg L, Monahan K. Age differences in resistance to peer influence. Dev Psychol. 2007;43:1531-1543.

104.2 Sexual Identity Development

Terms and Definitions

Sex Assigned at Birth

A newborn is assigned a sex before (ultrasound) or at the time of birth based on the external genitalia. In case of a disorder of sex development, these genitalia may appear ambiguous, and additional components of sex (e.g., chromosomal, gonadal, hormonal sex) are assessed. In consultation with specialists, parents assign the child a sex that they believe is most likely to be consistent with gender identity, which cannot be assessed until later in life (Chapter 582).

Factors That Influence Sexual Identity Development

During prenatal sexual development, a gene located on the Y chromosome (XRY) induces the development of testes. The hormones produced by the testes direct sexual differentiation in the male direction resulting in the development of male internal and external genitalia. In the absence of this gene in XX chromosomal females, ovaries develop and sexual differentiation proceeds in the female direction resulting in female internal and external genitalia. These hormones may also play a role in sexual differentiation of the brain. In disorders of sex development, chromosomal and prenatal hormonal sex varies from this typical developmental pattern and may result in ambiguous genitalia at birth (Chapter 582).

Some evidence has been found for the impact of biologic and environmental factors on social sex role and gender role behavior, while their impact on gender identity remains less clear. Animal research has shown the influence of prenatal hormones on sexual differentiation of the brain. In humans, prenatal exposure to unusually high levels of androgens in girls with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) has been associated with more masculine gender role behavior, gender variant identity, and same-sex sexual orientation, but cannot account for all of the variance found (Chapter 570). Research on environmental factors has focused on the influence of sex-typed socialization. Social sex role stereotypes develop early in life. Until later in adolescence, boys and girls are typically socially segregated by gender, reinforcing sex-typed characteristics such as boys’ focus on rough-and-tumble play and asserting dominance, and girls focus on verbal communication and creating relationships. Parents, other adults, teachers, peers, and the media serve as gender socializing role models and agents by treating boys and girls differently.

For information on the development of sexual orientation, see Chapter 104.3.

Gender Variance/Gender Role Nonconformity Among Children and Adolescents

Gender Variant Identity/Transgender Children and Adolescents

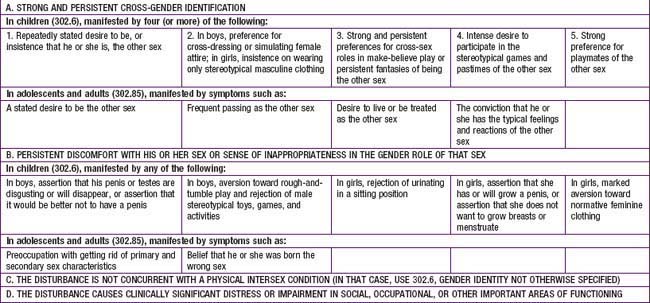

The Diagnosis of Gender Identity Disorder: Criteria and Critique

Gender identity disorder is classified as a mental disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and International Classification of Diseases, which, particularly for children, is controversial. Diagnostic criteria conflate gender variant identity with gender variant behavior. A child could receive the DSM diagnosis without having indicated “a repeated stated desire to be or insistence that he or she is, the other sex,” because only 4 of the 5 A category criteria need to be met (Table 104-6). Critics have argued that the distress children experience is mainly the result of social stigma rather than “a manifestation of a behavioral, psychological, or biological dysfunction in the individual” and hence would not meet the definition of a mental disorder. Critics have also expressed concern about children with normal variation in gender role being labeled with a mental disorder perpetuating social stigma, yet there is a tendency of clinicians to underdiagnose rather than overdiagnose children whose gender variance goes beyond behavior and who report gender dysphoria. These children could potentially benefit from the diagnosis to receive early treatment in the form of support, education, advocacy, and, in case of persistent and severe gender dysphoria, puberty-delaying hormone therapy as a reversible precursor to feminizing or masculinizing hormone therapy.

Interventions and Treatment

Pediatricians who encounter transgender youth in their practice should be careful not to make assumptions about gender and sexual identity, but rather ask youth how they would describe themselves. This includes asking if they like being a boy or girl, have ever questioned this, or wished they were born the other sex; have a preferred nickname or pronoun (he or she; if not sure, avoid pronouns); and how they feel about their maturing body and sex characteristics, and what they would change about that if they could. Extra caution should be exercised during physical and genital exams because transgender youth may be particularly uncomfortable with their anatomy. When considering contraceptive options for female-to-males, alternatives to feminizing agents should be explored. For transgender-specific medical interventions, transgender youth should be referred to specialists in the treatment of gender dysphoria (see World Professional Association for Transgender Health, www.wpath.org). For other health concerns, ensure referral to transgender or gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgendered (GLBT) friendly providers, especially in the case of gender segregated treatment facilities. Advocates for Youth (www.advocatesforyouth.org) and Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (www.pflag.org) offer excellent support resources for transgender youth and their families.

Biro FM. Puberty. Adolesc Med. 2007;18:425-433.

Bockting WO, Goldberg JM, editors. Guidelines for transgender care. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Medical Press, 2007.

Cohen-Kettenis PT, Pfäfflin F. Transgenderism and intersexuality in childhood and adolescence: making choices. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003.

2004 Frankowski BL and the Committee on Adolescence: Sexual orientation and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1827-1832.

Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis P, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, et al. Endocrine treatment of transsexual persons: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3132-3134.

Lee PA, Houk C, Ahmed SF, et al. International consensus conference on intersex organized by the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society and the European Society for Paediatrics Endocrinology. Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. Pediatrics. 2006;118:814-815.

Meyer WIII, Blocking W, Cohen-Kettenis PT, et al. The standards of care for gender identity disorders, sixth version. J Psychol Hum Sexuality. 2001;13:130.

Olson J, Forbes C, Belzer M. Management of the transgender adolescent. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(2):171-176.

104.3 Adolescent Homosexuality

Implications for Health

Medical Threats to Health

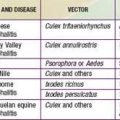

Homosexual adolescents generally have the same medical concerns as heterosexual youths. Risky sexual behaviors, not sexual orientation, endanger health. The most common and serious sexually-related conditions arise from unprotected anal intercourse. The epithelial surfaces of the fragile rectal mucosa can be easily damaged during sex, facilitating the transmission of pathogens. Rectal intercourse has been shown to be the most efficient route of infection by hepatitis B (Chapter 350), cytomegalovirus (Chapter 247), and HIV (Chapter 268). Oral-anal or digital-anal contact can transmit enteric pathogens, such as the hepatitis A virus. Unprotected oral sex also can lead to oropharyngeal disease in the receptive partner and gonococcal and non-gonococcal urethritis for the insertive partner. Certain STIs, particularly ulcerative diseases, such as syphilis and herpes simplex virus infection, facilitate the spread of HIV.

Recommendations for Care

Prevention, Treatment, and Referrals

In addition, though firm recommendations are pending, some specialists routinely obtain type-specific serologic tests for herpes simplex virus-2 and vaccinate gay adolescents and other young MSM with Gardasil preventatively. For treatment of STIs, see Chapter 114. Complicated STIs and HIV infection warrant referral to medical subspecialists.

Horvath KJ, Rosser BR, Remafedi G. Sexual risk taking among young internet-using men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1059-1067.

Mustanski BS, Chivers ML, Bailey JM. A critical review of recent biological research on human sexual orientation. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2002;13:89-140.

Remafedi G. Sexual orientation and youth suicide. JAMA. 1999;282:1291-1292.

Russell ST, Franz BT, Driscoll AK. Same-sex romantic attraction and experiences of violence in adolescence. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:903-906.

Savin-Williams RC, Diamond LM. Sexual identity trajectories among sexual-minority youths: gender comparisons. Arch Sex Behav. 2000;29:607-627.

Valleroy LA, MacKellar DA, Karon JM, et al. HIV prevalence and associated risks in young men who have sex with men. JAMA. 2000;84:198-204.

yr. This is followed by penile growth during SMR3. Peak growth occurs when testis volumes reach approximately 9-10 cm3 during SMR4. Under the influence of LH and testosterone, the seminiferous tubules, epididymis, seminal vesicles, and prostate enlarge. The left testis normally is lower than the right. Some degree of breast hypertrophy, typically bilateral, occurs in 40-65% of boys during SMR2-3 due to a relative excess of estrogenic stimulation.

yr. This is followed by penile growth during SMR3. Peak growth occurs when testis volumes reach approximately 9-10 cm3 during SMR4. Under the influence of LH and testosterone, the seminiferous tubules, epididymis, seminal vesicles, and prostate enlarge. The left testis normally is lower than the right. Some degree of breast hypertrophy, typically bilateral, occurs in 40-65% of boys during SMR2-3 due to a relative excess of estrogenic stimulation.