Chapter 10 Addiction and Abuse

There are many variations of the definition of addiction. In medical terms, addiction can be characterized as recurrent or relapsing behavior that results in a rewarding experience but also results in harm. Other features of addiction include a very strong motivation to participate in a given behavior (such as taking a drug), loss of control in regulating this behavior, and the presence of an unpleasant experience when the behavior is not performed. Addictions are chronic problems that are very difficult to treat and overcome.

Addiction can be described as occurring in cycles. The three general cycles include the following:

This chapter focuses on addictions related to substance abuse, but it is important to recognize that addictions can be unrelated to substance abuse and still possess many common neurologic mechanisms; a common example of addiction that is not related to substance abuse is gambling.

Scope of the Substance Abuse Problem

The statistics in Table 10-1 are from a 2007 survey in the United States by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and provide some information regarding the incidence of substance abuse.

TABLE 10-1 Survey by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2007)

| Incidence of Substance Use | Number | Proportion of U.S. Population |

|---|---|---|

| Adults who will have engaged in nonmedical or illicit drug use at some time during their lifetime | 29 million | 15.6% |

| Adults who will develop substance dependence on illicit drugs during their lifetime | 5.4 million | 2.9% |

| People over the age of 12 who are current users of alcohol | 120 million | 51% |

| People over the age of 12 who met the criteria for alcohol dependence | 18 million | 7.7% |

| People aged 12 or older who were current (past month) users of a tobacco product | 70.9 million | 28.6% |

| People aged 12 or older who were current cigarette smokers | 60.1 million | 24.2% |

Many different terms are used to describe different components that are related to addiction, and it is important to highlight these terms and provide clear definitions.

Dependence: Physiologic condition whereby the absence of a drug results in withdrawal signs and symptoms. It is very closely related to the psychologic processes that occur with addiction, because the body and the mind are not completely separate entities (when you are physically unwell, you do not feel good), but strictly speaking, dependence refers to only the physical component of addiction.

Dependence: Physiologic condition whereby the absence of a drug results in withdrawal signs and symptoms. It is very closely related to the psychologic processes that occur with addiction, because the body and the mind are not completely separate entities (when you are physically unwell, you do not feel good), but strictly speaking, dependence refers to only the physical component of addiction. Withdrawal: Physical and/or emotional reaction that occurs when a drug is not administered to an individual who is addicted. These experiences are dysphoric (unpleasant) and will be described in more detail.

Withdrawal: Physical and/or emotional reaction that occurs when a drug is not administered to an individual who is addicted. These experiences are dysphoric (unpleasant) and will be described in more detail. Tolerance: Phenomenon whereby performing a behavior results in a smaller reward than previous, similar behaviors. As a result, the behavior is often adjusted upward to reproduce the same magnitude of reward that was previously experienced. Increasing the dose of a drug would be an example of an upwardly adjusted behavior, as would gambling with a larger amount of money.

Tolerance: Phenomenon whereby performing a behavior results in a smaller reward than previous, similar behaviors. As a result, the behavior is often adjusted upward to reproduce the same magnitude of reward that was previously experienced. Increasing the dose of a drug would be an example of an upwardly adjusted behavior, as would gambling with a larger amount of money. Obsession: Recurring thought. For example, thinking nonstop about taking a drug would constitute an obsession.

Obsession: Recurring thought. For example, thinking nonstop about taking a drug would constitute an obsession. Compulsion: Recurring behavior. For example, actually taking a drug over and over would be a compulsion.

Compulsion: Recurring behavior. For example, actually taking a drug over and over would be a compulsion. Craving: Psychologic process similar to craving. It is also characterized by anticipation and strong desire.

Craving: Psychologic process similar to craving. It is also characterized by anticipation and strong desire. Substance abuse: Pattern of inappropriate or illicit use of substances for physiologic or psychologic reward.

Substance abuse: Pattern of inappropriate or illicit use of substances for physiologic or psychologic reward. Positive reinforcement: When exposure to a stimulus results in a reward and increases the probability of repeating the behavior in future (e.g., getting paid for a job well done).

Positive reinforcement: When exposure to a stimulus results in a reward and increases the probability of repeating the behavior in future (e.g., getting paid for a job well done). Negative reinforcement: When removal of a stimulus avoids or reduces bad feelings (e.g., taking your hand out of boiling water).

Negative reinforcement: When removal of a stimulus avoids or reduces bad feelings (e.g., taking your hand out of boiling water).A motivational framework can be used to help describe the difference between positive and negative reinforcement. In persons who are driven more by impulse, there is a state of arousal and tension before the addictive behavior is performed, and the behavior results in pleasant feelings. This would be an example of positive reinforcement. In contrast, compulsive behavior is characterized by stress and anxiety before the addictive behavior is performed, and the behavior results in relief from those feeling. This would be an example of negative reinforcement.

Throughout the time course of addiction development, the initial behaviors are primarily driven by impulse, whereas the latter stages of addiction are driven by a combination of both impulse and compulsion, and there is a shift from positive reinforcement to negative reinforcement.

Neurophysiology of Addiction

Studies to determine the neural pathways involved in addiction have involved both human and animal populations and focus on attempts to precisely stimulate or inhibit different regions of the brain and measure outcomes related to these interventions. The pathways are complex and beyond the scope of this text; however, a simplified description of the more important components will be presented.

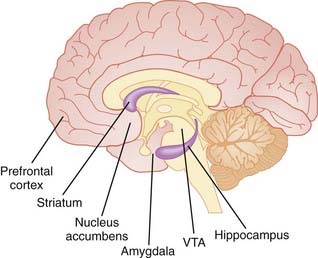

There are some important details related to neuroanatomy that are relevant to understanding the pathways of addiction; some of them include the following (Figure 10-1):

Mesolimbic system: Pathway in the brain that projects from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens, amygdala, limbic system, and other areas of the brain. It is strongly implicated in addiction and dopamine processing.

Mesolimbic system: Pathway in the brain that projects from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens, amygdala, limbic system, and other areas of the brain. It is strongly implicated in addiction and dopamine processing. VTA: Tegment is Latin for covering (integument means skin). The VTA is located on the floor of the midbrain and is responsible for reward signaling, motivation, and some psychiatric disorders. It is strongly implicated in dopamine processing.

VTA: Tegment is Latin for covering (integument means skin). The VTA is located on the floor of the midbrain and is responsible for reward signaling, motivation, and some psychiatric disorders. It is strongly implicated in dopamine processing. Amygdala: Latin for almond. The amygdala is an almond-shaped group of nuclei deep in the brain near the medial temporal lobes. It is primarily responsible for processing of emotion, especially fear and anxiety.

Amygdala: Latin for almond. The amygdala is an almond-shaped group of nuclei deep in the brain near the medial temporal lobes. It is primarily responsible for processing of emotion, especially fear and anxiety.Dopamine-Release Theory

All behaviors of addiction activate and increase dopamine signaling in the mesolimbic system. However, there is also evidence to suggest that dopamine-independent processing occurs in the nucleus accumbens.

Associated with the dopamine release theory is the concept of predicted and actual reward. This hypothesis suggests that dopamine release in the mesolimbic system represents a learning signal that reinforces constructive behaviors.

An example would be a mouse that learns to pull a lever to obtain food. The pulling of the lever leads to dopamine release, as the animal is predicting a reward, whereas the actual reward (food) does not elicit a response.

An example would be a mouse that learns to pull a lever to obtain food. The pulling of the lever leads to dopamine release, as the animal is predicting a reward, whereas the actual reward (food) does not elicit a response. Drugs that release dopamine into this pathway generate an “inappropriate” learning signal, one that suggests that the behavior (e.g., taking of the drug) should be repeated.

Drugs that release dopamine into this pathway generate an “inappropriate” learning signal, one that suggests that the behavior (e.g., taking of the drug) should be repeated.The degree of importance given to dopamine in addiction remains controversial; however, one thing is clear—several addictive drugs target the dopamine pathway.

A number of classes of compounds are associated with addiction. Some of these, such as the opioids, sedative-hypnotics, cannabinoids, and central nervous system (CNS) stimulants are also covered elsewhere in this textbook. The following summaries focus on the aspects of these compounds that are related to addiction. There are two key common features to note as you progress through the following summaries:

Speed of onset is vital. A key distinguishing feature of an addictive substance is a rapid onset of action. This is why most of the substances listed in the following pages are delivered by routes that facilitate quick onset (i.e., intravenous, intranasal, inhalation). This also explains why heroin, which has a rapid onset of action, is considered to be one of the most addictive of opioids.

Speed of onset is vital. A key distinguishing feature of an addictive substance is a rapid onset of action. This is why most of the substances listed in the following pages are delivered by routes that facilitate quick onset (i.e., intravenous, intranasal, inhalation). This also explains why heroin, which has a rapid onset of action, is considered to be one of the most addictive of opioids. Withdrawal is the opposite of the reward. This is a key reason why substance addictions are so difficult to overcome. If a drug causes euphoria, withdrawal will cause dysphoria; if a drug is a depressant, then withdrawal will cause excitation (anxiety, seizures). Therefore when trying to maintain abstinence, not only must a patient cope with the loss of reward, they must also withstand symptoms that are the opposite of reward.

Withdrawal is the opposite of the reward. This is a key reason why substance addictions are so difficult to overcome. If a drug causes euphoria, withdrawal will cause dysphoria; if a drug is a depressant, then withdrawal will cause excitation (anxiety, seizures). Therefore when trying to maintain abstinence, not only must a patient cope with the loss of reward, they must also withstand symptoms that are the opposite of reward.Opioids

All of the opioids have abuse potential, although their primary use is in analgesia. Heroin is primarily used as a substance of abuse; therefore it is the focus of the following discussion.

Mechanism

Opioids act as agonists at opioid receptors throughout the body; however the µ receptor mediates their euphoric effects.

Actions

Heroin is much more lipophilic than other opioids and therefore crosses into the brain much more readily, leading to a rapid and dramatic onset of action. It can be injected, smoked or introduced via the intranasal route.

Toxicity

The main toxicity of concern with use of any opioid is respiratory depression, as the patient can eventually stop breathing at high enough doses. Other signs of toxicity include obtundation and miosis (constricted pupils).

The main toxicity of concern with use of any opioid is respiratory depression, as the patient can eventually stop breathing at high enough doses. Other signs of toxicity include obtundation and miosis (constricted pupils). Acute overdose of heroin and other opiates can be treated with intravenous naloxone, an opioid antagonist. The effects of naloxone can be quite dramatic, rapidly reversing the effects of opioid toxicity. However, it must be noted that naloxone also has a relatively short duration of action, and if the elimination half-life of the opioid exceeds that of naloxone, the antagonist may wear off before the opioid has reached safe plasma levels, and respiratory depression can recur. Therefore overdose patients treated with naloxone should be monitored carefully.

Acute overdose of heroin and other opiates can be treated with intravenous naloxone, an opioid antagonist. The effects of naloxone can be quite dramatic, rapidly reversing the effects of opioid toxicity. However, it must be noted that naloxone also has a relatively short duration of action, and if the elimination half-life of the opioid exceeds that of naloxone, the antagonist may wear off before the opioid has reached safe plasma levels, and respiratory depression can recur. Therefore overdose patients treated with naloxone should be monitored carefully.Important Notes

Tolerance to opioids does not typically begin until after a few weeks of use. Most of the effects of opioids are prone to tolerance, with the exception of constipation and convulsions. The extent of tolerance can be significant.

Tolerance to opioids does not typically begin until after a few weeks of use. Most of the effects of opioids are prone to tolerance, with the exception of constipation and convulsions. The extent of tolerance can be significant. Signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal include sweating, runny nose, tearing, and yawning initially, followed by:

Signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal include sweating, runny nose, tearing, and yawning initially, followed by:

Various pharmacologic strategies have been employed to reduce the effects of opioid withdrawal. Opioid antagonists such as naltrexone have been used, but patient adherence is poor.

Various pharmacologic strategies have been employed to reduce the effects of opioid withdrawal. Opioid antagonists such as naltrexone have been used, but patient adherence is poor. Another approach to withdrawal from heroin has been to substitute the longer-acting oral agent methadone. Methadone is eliminated much more slowly than heroin, allowing for a much more gradual withdrawal. It is also an N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist, and this is believed to play a role in preventing tolerance to methadone.

Another approach to withdrawal from heroin has been to substitute the longer-acting oral agent methadone. Methadone is eliminated much more slowly than heroin, allowing for a much more gradual withdrawal. It is also an N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist, and this is believed to play a role in preventing tolerance to methadone. Because opioid withdrawal can be physically severe and difficult to manage without support, many patients require medically supervised opioid detox as the first step before beginning maintenance therapy or long-term treatment.

Because opioid withdrawal can be physically severe and difficult to manage without support, many patients require medically supervised opioid detox as the first step before beginning maintenance therapy or long-term treatment.Ethanol

Ethanol is one of the oldest and definitely the most widely accepted drug of abuse. It is available legally and quite readily in most jurisdictions.

Mechanism

Ethanol is a CNS depressant. It has multiple effects in the CNS, some established and others still in question. The following discussion will focus on established mechanisms.

Ethanol is a CNS depressant. It has multiple effects in the CNS, some established and others still in question. The following discussion will focus on established mechanisms. Ethanol potentiates γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS, as well as inhibiting glutamate, the major excitatory neurotransmitter. The effect of both is to promote inhibition.

Ethanol potentiates γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS, as well as inhibiting glutamate, the major excitatory neurotransmitter. The effect of both is to promote inhibition. The effects on GABA and glutamate neurotransmission are important not only for the effects of ethanol consumption, but also for the withdrawal after chronic use. Removal of the inhibitory effects of ethanol can lead to excess excitation, manifested as seizures.

The effects on GABA and glutamate neurotransmission are important not only for the effects of ethanol consumption, but also for the withdrawal after chronic use. Removal of the inhibitory effects of ethanol can lead to excess excitation, manifested as seizures.Actions

The actions of ethanol are dose dependent and are listed here in order of increasing dose:

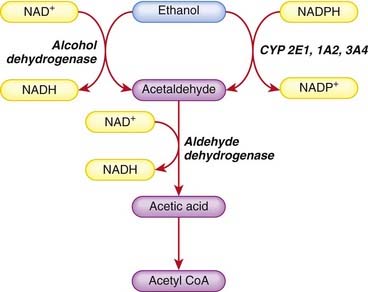

Ethanol is metabolized in the liver, oxidized to acetaldehyde primarily by alcohol dehydrogenase with a minor secondary CYP450 pathway, and then oxidized further to acetic acid by aldehyde dehydrogenase. The acetic acid is broken down to acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) as well as CO2 and water (Figure 10-2).

Ethanol is metabolized in the liver, oxidized to acetaldehyde primarily by alcohol dehydrogenase with a minor secondary CYP450 pathway, and then oxidized further to acetic acid by aldehyde dehydrogenase. The acetic acid is broken down to acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) as well as CO2 and water (Figure 10-2). Two steps in this metabolic process require nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)+; therefore NAD+ quickly becomes depleted when ethanol is being metabolized. This limits the amount of ethanol that can be metabolized to a constant amount (zero-order kinetics) per unit of time (about 120 mg/kg/hr).

Two steps in this metabolic process require nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)+; therefore NAD+ quickly becomes depleted when ethanol is being metabolized. This limits the amount of ethanol that can be metabolized to a constant amount (zero-order kinetics) per unit of time (about 120 mg/kg/hr). Depletion of NAD+, a cofactor in a number of metabolic processes, also leads to the accumulation of lactate and lactic acidosis.

Depletion of NAD+, a cofactor in a number of metabolic processes, also leads to the accumulation of lactate and lactic acidosis.Toxicity

Ethanol has both acute and chronic toxic effects. The acute effects are summarized in the previous section and are dose dependent, up to and including death. Chronic effects of alcohol abuse are listed here.

Liver: The metabolites of ethanol, specifically acetaldehydes, bind proteins, and these adducts can then stimulate an immune reaction, which damages tissue. Eventually this can lead to cirrhosis and liver failure.

Liver: The metabolites of ethanol, specifically acetaldehydes, bind proteins, and these adducts can then stimulate an immune reaction, which damages tissue. Eventually this can lead to cirrhosis and liver failure. Brain: Ethanol inflicts both reversible and irreversible damage to the brain. Chronic abuse leads to cognitive impairment, although it is not clear whether moderate drinking has any effects on the brain.

Brain: Ethanol inflicts both reversible and irreversible damage to the brain. Chronic abuse leads to cognitive impairment, although it is not clear whether moderate drinking has any effects on the brain.

There are several mechanisms for the brain damage, including up-regulation of glutamate receptors, which leads to excitotoxicity. Chronic ethanol exposure may also deplete neurotrophins, factors that promote neuronal survival. Adduct formation, as noted previously for the liver, is also responsible for some of the damage.

There are several mechanisms for the brain damage, including up-regulation of glutamate receptors, which leads to excitotoxicity. Chronic ethanol exposure may also deplete neurotrophins, factors that promote neuronal survival. Adduct formation, as noted previously for the liver, is also responsible for some of the damage. Cardiovascular system: Chronic alcohol abuse has been associated with hypertension, arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, and stroke. Chronic ethanol abuse leads to oxidative stress and disruption of ion channels and may inhibit protein synthesis, all of which can lead to cardiovascular complications.

Cardiovascular system: Chronic alcohol abuse has been associated with hypertension, arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, and stroke. Chronic ethanol abuse leads to oxidative stress and disruption of ion channels and may inhibit protein synthesis, all of which can lead to cardiovascular complications.Important Notes

Acute management of ethanol intoxication involves maintaining respiration and providing intravenous support with fluid and electrolytes until the body is able to metabolize the excess down to a safer blood alcohol concentration. In some jurisdictions, metadoxine is used to facilitate the elimination of ethanol.

Acute management of ethanol intoxication involves maintaining respiration and providing intravenous support with fluid and electrolytes until the body is able to metabolize the excess down to a safer blood alcohol concentration. In some jurisdictions, metadoxine is used to facilitate the elimination of ethanol. Signs and symptoms of ethanol withdrawal after chronic use include tremor, tachycardia, sweating, anxiety, hallucinations, insomnia, and elevated blood pressure. These signs and symptoms typically begin within 12 hours of the last drink and begin to decline after 4 to 5 days. As noted previously, seizures can also occur.

Signs and symptoms of ethanol withdrawal after chronic use include tremor, tachycardia, sweating, anxiety, hallucinations, insomnia, and elevated blood pressure. These signs and symptoms typically begin within 12 hours of the last drink and begin to decline after 4 to 5 days. As noted previously, seizures can also occur. Withdrawal is often treated with benzodiazepines. There is some concern about the use of these agents to treat dependence, given their own tendency to elicit physical dependence. Alternatives that have been tried with some success include nitrous oxide and antiseizure medications.

Withdrawal is often treated with benzodiazepines. There is some concern about the use of these agents to treat dependence, given their own tendency to elicit physical dependence. Alternatives that have been tried with some success include nitrous oxide and antiseizure medications. Disulfuram, a drug that inhibits aldehyde dehydrogenase, has also been used to assist alcoholics in maintaining abstinence. Inhibition of this enzyme leads to a buildup of acetaldehyde, a substance responsible for many of the unpleasant side effects of ethanol: nausea, vomiting, flushing, and headache.

Disulfuram, a drug that inhibits aldehyde dehydrogenase, has also been used to assist alcoholics in maintaining abstinence. Inhibition of this enzyme leads to a buildup of acetaldehyde, a substance responsible for many of the unpleasant side effects of ethanol: nausea, vomiting, flushing, and headache. Tolerance to the effects of ethanol can develop. This occurs in part because of induction of ethanol metabolism. As an adjustment to chronic use, the liver will induce CYP450 enzymes involved in ethanol metabolism. This enzyme induction can also affect the metabolism of other drugs that use those isozymes for their elimination.

Tolerance to the effects of ethanol can develop. This occurs in part because of induction of ethanol metabolism. As an adjustment to chronic use, the liver will induce CYP450 enzymes involved in ethanol metabolism. This enzyme induction can also affect the metabolism of other drugs that use those isozymes for their elimination.Central Nervous System Stimulants

Cocaine is the most well-known CNS stimulant of abuse. Amphetamines are another class of CNS stimulants that are used as drugs of abuse, and they are discussed in the chapter on CNS stimulants.

Mechanism

Cocaine is a sympathomimetic. It acts as a reuptake inhibitor, nonspecifically inhibiting reuptake of several catecholamines, including dopamine, which is the neurotransmitter most likely responsible for its reinforcing effects. Inhibition of neurotransmitter reuptake increases the concentration and prolongs the actions of these transmitters in the synapse, enhancing their effects.

Cocaine is a sympathomimetic. It acts as a reuptake inhibitor, nonspecifically inhibiting reuptake of several catecholamines, including dopamine, which is the neurotransmitter most likely responsible for its reinforcing effects. Inhibition of neurotransmitter reuptake increases the concentration and prolongs the actions of these transmitters in the synapse, enhancing their effects.Actions

Cocaine produces arousal and increased alertness and enhances self-confidence and sense of well-being. Euphoria is experienced at higher doses.

Cocaine produces arousal and increased alertness and enhances self-confidence and sense of well-being. Euphoria is experienced at higher doses.Toxicity

Important Notes

Signs and symptoms of cocaine withdrawal are typically the opposite of the effects seen with the drug: fatigue, dysphoria, depression, and bradycardia.

Signs and symptoms of cocaine withdrawal are typically the opposite of the effects seen with the drug: fatigue, dysphoria, depression, and bradycardia. Symptoms of withdrawal from cocaine are usually relatively mild and do not typically need to be managed by other drug therapy. Behavioral interventions are the primary strategy employed to promote and sustain abstinence.

Symptoms of withdrawal from cocaine are usually relatively mild and do not typically need to be managed by other drug therapy. Behavioral interventions are the primary strategy employed to promote and sustain abstinence. When drug therapy is attempted, agents that enhance GABA are often used, including benzodiazepines and baclofen (GABAB agonist). The inhibitory effects of GABA are thought to ease withdrawal from the stimulatory effects of cocaine. Clonidine is also used to treat withdrawal.

When drug therapy is attempted, agents that enhance GABA are often used, including benzodiazepines and baclofen (GABAB agonist). The inhibitory effects of GABA are thought to ease withdrawal from the stimulatory effects of cocaine. Clonidine is also used to treat withdrawal. Perhaps because of the milder withdrawal symptoms, cocaine tends to be used less regularly than other addictive substances such as nicotine and opioids.

Perhaps because of the milder withdrawal symptoms, cocaine tends to be used less regularly than other addictive substances such as nicotine and opioids.Cannabis

The use of cannabis and related compounds in therapeutics is covered in Chapter 15. In this section, the focus will be on the use of cannabis as a substance of abuse.

Mechanism

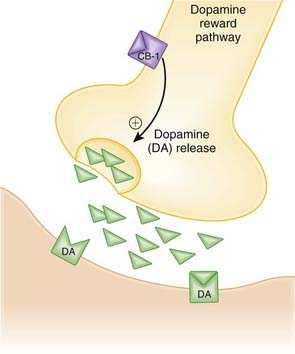

Cannabinoid (CB1) receptors in the reward pathways of the brain are stimulated by cannabinoids such as cannabis, leading to the euphoric effects associated with this drug (Figure 10-3).

Actions

Cannabis is highly lipid soluble and when smoked has a rapid onset of action. The onset is much slower when the drug is swallowed.

Toxicity

Cannabis is considered to be a relatively safe drug in acute use. Acutely, psychiatric disturbances, including psychotic episodes, have been reported.

Cannabis is considered to be a relatively safe drug in acute use. Acutely, psychiatric disturbances, including psychotic episodes, have been reported.Important Notes

Cannabis is not a drug commonly associated with overdose situations, and there are therefore no drugs that are typically used to manage overdose with cannabis.

Cannabis is not a drug commonly associated with overdose situations, and there are therefore no drugs that are typically used to manage overdose with cannabis. For a number of years, the conventional wisdom was that cannabis was not addictive. However, with the current understanding of the mechanism of cannabis—namely that it activates the same dopamine reward pathways as many other addictive substances—it is believed that it is possible to develop a physical dependence on cannabis. This has significant implications for treatment of chronic cannabis use.

For a number of years, the conventional wisdom was that cannabis was not addictive. However, with the current understanding of the mechanism of cannabis—namely that it activates the same dopamine reward pathways as many other addictive substances—it is believed that it is possible to develop a physical dependence on cannabis. This has significant implications for treatment of chronic cannabis use. Another sign that cannabis may be capable of eliciting physical dependence is that it has been associated with a withdrawal effect. Cannabis withdrawal may include anxiety, irritability, dysphoria, and anorexia.

Another sign that cannabis may be capable of eliciting physical dependence is that it has been associated with a withdrawal effect. Cannabis withdrawal may include anxiety, irritability, dysphoria, and anorexia. Both naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, and rimonabant, a CB1 antagonist, have been used in the facilitation of cannabis abstinence. Successes have been reported with each, although rimonabant has been withdrawn from the market or failed to be approved in many jurisdictions because of psychiatric side effects, including suicide.

Both naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, and rimonabant, a CB1 antagonist, have been used in the facilitation of cannabis abstinence. Successes have been reported with each, although rimonabant has been withdrawn from the market or failed to be approved in many jurisdictions because of psychiatric side effects, including suicide.Hallucinogens

The term hallucinogen is often used to describe a broad category of drugs that cause hallucinations in users. These drugs are also referred to as psychedelics. Examples include the following:

Mechanism

Actions

LSD

Disorders of perception include altered shapes and colors, sharpened sense of hearing, and difficulty focusing on objects.

Disorders of perception include altered shapes and colors, sharpened sense of hearing, and difficulty focusing on objects. Psychologic effects include changes in mood, lapses in judgment, impaired ability to express thoughts, and hallucinations.

Psychologic effects include changes in mood, lapses in judgment, impaired ability to express thoughts, and hallucinations.Toxicity

LSD

Acutely, LSD and LSD-related hallucinogens do not appear to have any direct serious effects on the body in overdose situations.

Acutely, LSD and LSD-related hallucinogens do not appear to have any direct serious effects on the body in overdose situations.Important Notes

LSD users can experience a bad trip, essentially a negative hallucinatory experience, which can be quite stressful and lead to agitation. Patients are usually treated supportively, with reassurance, although an anxiolytic such as diazepam may also be indicated.

LSD users can experience a bad trip, essentially a negative hallucinatory experience, which can be quite stressful and lead to agitation. Patients are usually treated supportively, with reassurance, although an anxiolytic such as diazepam may also be indicated. With the exception of LSD itself, the LSD-related hallucinogens do not act through the dopamine reward pathway. It is therefore believed they might have less propensity for dependence.

With the exception of LSD itself, the LSD-related hallucinogens do not act through the dopamine reward pathway. It is therefore believed they might have less propensity for dependence. LSD does stimulate the dopamine reward pathway, and there are some indications that dependence is more likely with this agent.

LSD does stimulate the dopamine reward pathway, and there are some indications that dependence is more likely with this agent.Inhalants

Inhalants—agents that are abused via the inhalational route—range from the anesthetic gases such as nitrous oxide, described elsewhere in this textbook, to industrial solvents such as gasoline, to organic nitrates. Industrial solvents and organic nitrates are considered here.