Chapter 36 Acute gastrointestinal bleeding

Acute gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a common admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Peptic ulcer disease accounts for 75% of upper GI bleeding.1,2 Bleeding from varices, oesophagitis, duodenitis and Mallory–Weiss syndrome each account for between 5% and 15% of cases. About 20% of GI bleeding arises from the lower GI tract. Common aetiological causes for GI bleeding are listed in Table 36.1. Mortality from upper GI bleeding has remained at approximately 10% for decades, but recent reports suggest that mortality from bleeding ulcers has fallen substantially to about 5%.3 On the other hand, variceal bleeding has a much higher mortality of about 30%. Risk factors for mortality include old age, associated medical problems, coagulopathy and magnitude of bleeding.

Table 36.1 Common causes of acute gastrointestinal bleeding

| Upper gastrointestinal bleeding |

| Peptic ulcers (DU:GU 3:1) |

| Varices (oesophageal varices:gastric varices 9:1) |

| Portal hypertensive gastropathy |

| Mallory–Weiss syndrome |

| Gastritis, duodenitis and oesophagitis |

| Lower gastrointestinal bleeding |

| Diverticular bleeding |

| Angiodysplasia and arteriovenous malformation |

| Colonic polyps or tumours |

| Meckel’s diverticulum |

| Inammatory bowel diseases |

DU, duodenal ulcer; GU, gastrointestinal ulcer.

UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

INVESTIGATION

ENDOSCOPY OR BARIUM STUDY

MANAGEMENT OF NON-VARICEAL UPPER GI BLEEDING

RESUSCITATION

Blood and plasma expanders should be given through large-bore intravenous cannulae. Vital signs should be closely monitored. In patients with hypovolaemic shock, central venous pressure and hourly urine output should also be observed (see Chapter 11). Following adequate resuscitation, management is directed to identify the lesion and distinguish the high-risk patient, who is likely to require early endoscopic or surgical treatment.

THE HIGH-RISK PATIENT

Significant GI bleeding is indicated by syncope, haematemesis, systolic blood pressure below 100 mmHg (13.3 kPa), postural hypotension and, if more than 4 units of blood have to be transfused in 12 hours, to maintain blood pressure. Patients over 60 years old and with multiple underlying diseases are at even higher risk.3 Those admitted for other medical problems (e.g. heart or respiratory failure, or cerebrovascular bleed) and who have GI bleeding during hospitalisation also have a higher mortality.

THE HIGH-RISK ULCER

Peptic ulcers that are actively bleeding or have bled recently may show stigmata of haemorrhage on endoscopy. These include localised active bleeding (i.e. pulsatile, arterial spurting or simple oozing), an adherent blood clot, a protuberant vessel or a flat pigmented spot on the ulcer base. Stigmata of haemorrhage are important predictors of recurrent bleeding (Table 36.2). The proximal postero inferior wall of the duodenal bulb and the high lesser curve of the stomach are common sites for severe recurrent bleeding, due probably to their respective large arteries (gastroduodenal and left gastric arteries).

Table 36.2 Stigmata of haemorrhage and risk of recurrent bleeding in peptic ulcers

| Stigmata of haemorrhage | % recurrent bleeding |

|---|---|

| Spurter or oozer | 85–90 |

| Protuberant vessel | 35–55 |

| Adherent clot | 30–40 |

| Flat spot | 5–10 |

| None | 5 |

TREATMENT

Pharmacological control

Acid-suppressing drugs such as H2-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors are very effective drugs to promote ulcer healing. An acidic environment impairs platelet function and haemostasis. Therefore, reducing the secretion of gastric acid should reduce bleeding and encourage ulcer healing. A recent study has shown that potent acid suppression using intravenous proton pump inhibitors reduces recurrent bleeding after endoscopic therapy.4 Proton pump inhibitors should be recommended in high-risk peptic ulcer bleeding patients as an adjuvant to endoscopic therapy. In contrast, antifibrinolytic agents such as tranexamic acid have not been effective in reducing the operative rate and mortality of acute GI haemorrhage. Recent studies show that in patients at high risk of recurrent bleeding, pharmacologic control without endoscopic hemostasis is inadequate.5 Thus a combination of endoscopic and pharmacologic therapy offers the best therapy for ulcer bleeding patients.6,7

Endoscopic therapy

Adrenaline (epinephrine) injection

Endoscopic injection of adrenaline (1:10 000 dilution) at 0.5–1.0-ml aliquots (up to 10–15 ml) into and around the ulcer bleeding point has achieved successful haemostasis in over 90% of cases.6 Debate exists as to whether the haemostatic effect is a result of local tamponade by the volume injected, or vasoconstriction by adrenaline. Absorption of adrenaline into the systemic circulation has been documented, but without any significant effect on the haemodynamic status of the patient.8 Adrenaline injection is an effective, cheap, portable and easy-to-learn method of haemostasis, and has acquired worldwide popularity.

Coaptive coagulation

This method uses direct pressure and heat energy (heater probe) or electrocoagulation (bipolar coagulation probe (BICAP)) to control ulcer bleeding. The depth of tissue injury induced by these devices is minimised, as the bleeding vessel is tamponaded prior to coagulation. The overall efficacy of the adrenaline injection, heater probe and BICAP probe methods is comparable.9 Occasionally, it is not possible to obtain a view en face of the bleeding ulcers, particularly those on the lesser curve or on the posterior wall of the duodenal bulb. In these situations, direct pressure cannot be applied, and the failure rate of coaptive coagulation in these situations is expected to be higher.

Haemoclips

Endoscopic clipping of a bleeding vessel is an appealing alternative treatment which has gained popularity in recent years. The advantage of haemoclips over thermocoagulation is that there is no tissue injury induced and hence the risk of perforation is reduced. Studies comparing haemoclips against injection and thermocoagulation have shown favourable results.10,11 However, the application of haemoclips in certain sites, for example lesser curve, gastric fundus and posterior wall of the duodenum, is technically difficult. Loading of clips on to the application device is cumbersome and time-consuming and transfer of torque from the handle to the tip of the device is limited.

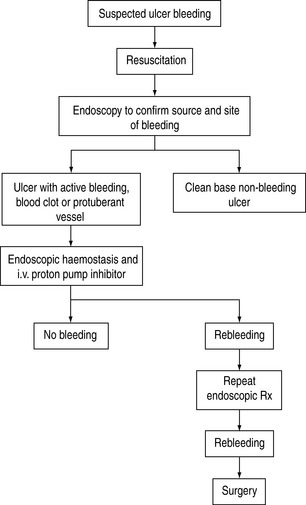

SURGERY

Surgical procedures include underrunning of the ulcer, underrunning plus vagotomy and drainage, and various types of gastrectomy. The overall mortality of emergency surgery for GI bleeding is about 15–20%. In a study investigating the best salvage treatment for patients with recurrent bleeding after endoscopic therapy, surgery was found to be comparable to repeating endoscopic treatment in securing hemostasis.12 However, morbidity is significantly higher in surgical patients than in endoscopic patients. Early surgery should be considered in patients with hypovolaemic shock and/or large peptic ulcer with protuberant vessels. A protocol to manage bleeding peptic ulcer is shown in Figure 36.1.13

ACUTE STRESS ULCERATION

Acute stress ulceration is associated with shock, sepsis, burns, multiple trauma, head injuries, spinal injuries and respiratory, renal and hepatic failure. Lesions are most commonly seen in the gastric fundus, and range from mild erosions to acute ulcerations. The exact mechanism leading to acute mucosal erosion/ulceration in critically ill patients is still unclear. Hypoxia and hypoperfusion of the gastroduodenal mucosa are probably the most important factors. Besides haemodynamic instability, respiratory failure and coagulopathy are also strong independent factors in critically ill patients. The incidence of stress-related mucosal bleeding in ICU patients has reported to range from 8 to 45%.14 It has been declining in the last decade as a result of highly effective management of hypotension and hypoxaemia. Bleeding may be occult or overt, from ‘coffee-grounds’ aspirates to frank haemorrhage.

PROPHYLAXIS AND TREATMENT

Significant ulcerations are managed as above. Minor bleeding and prophylactic treatment are considered together. Prophylactic treatment aims for gastric alkalinisation (gastric pH > 3.5), with the rationale that gastric acidity is the main cause of stress ulceration.14 The incidence of stress ulcerations appears to be lower with prophylactic gastric alkalinisation than with placebos, although an improvement in survival has not been shown.15,16 Gastric bacterial overgrowth and the associated nosocomial pneumonia have been concerns, but have not been substantiated by existing data. On balance, prophylactic treatment should probably be reserved only for at-risk patients. Scoring systems to estimate the risk of stress-ulcer bleeding have been proposed, for example Zinner and Tryba scores.17,18 The mainstay of prophylaxis and treatment for minor bleeding remains supportive – optimise oxygenation and tissue perfusion and control of infection. There is little consensus among critical care experts in the choice of prophylactic treatment used.19 Drugs given include the following:

Antacids

Antacids given hourly via a nasogastric tube can maintain gastric alkalinisation. Gastric pH monitoring is necessary. Antacids contain magnesium, aluminium, calcium or sodium, and complications may arise from excessive intake of these minerals. Bowel stasis and diarrhoea can also be problems. They are used less commonly now.

Sucralfate

This is a basic aluminium salt of sucrose octasulphate. It is effective in healing ulcers by increasing mucus secretion, mucosal blood flow and local prostaglandin production. These effects promote mucosal resistance against acid and pepsin (i.e. they are cytoprotective). As it does not alter gastric pH, Gram-negative bacterial colonisation of gastric juice is less likely. The incidence of nosocomial pneumonia may be less with sucralfate than with antacids or H2-receptor antagonists, but this is debatable and there is a potential risk of aspiration.15 Sucralfate is given via a nasogastric tube as 1.0 g every 4–6 hours. Constipation is a side-effect, and aluminium toxicity may arise from renal dysfunction.

H2-receptor antagonists

These drugs suppress acid secretion by competing for the histamine receptor on the parietal cell. Cimetidine is less potent and has interactions with anticonvulsants, theophyllines and warfarin. Famotidine and nizatidine are newer agents but have no particular advantage over ranitidine. The problem of H2-receptor antagonists is the development of tachyphylaxis after the first day of administration, leading to reduction of effectiveness in acid suppression. At least one meta-analysis showed that ranitidine did not confer any protection against stress ulcer in intensive care patients.21

Proton pump inhibitors

These are potent acid-suppressing agents as they block the final common pathway of acid secretion by the parietal cell, namely the proton pump. All proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole and rabeprazole) can be given as oral medication. Omeprazole and pantoprazole are also available in intravenous form for those who cannot be fed orally. In two non-randomized studies, intravenous omeprazole has been shown to protect critically ill patients who required ventilation from the development of stress-related mucosal bleeding from the upper GI tract.20 Yet, there are no prospective data indicating which are the high-risk patients who might benefit from this treatment.

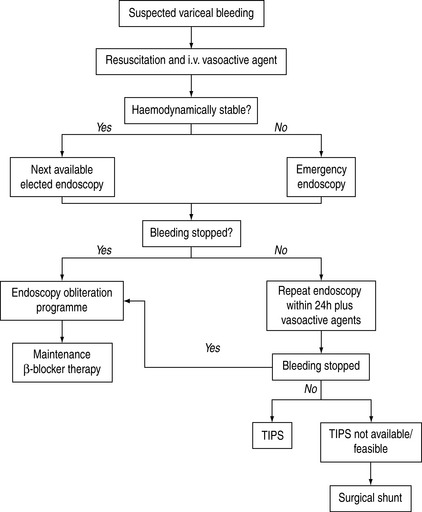

VARICEAL BLEEDING

Acute variceal bleeding is a serious complication of portal hypertension, with a high mortality. About 50% of patients with bleeding varices have had an earlier bleed during hospitalisation. The degree of liver failure, using Child–Pugh’s classification (see Chapter 38), is the most important prognostic factor for early rebleeding and survival.

PHARMACOLOGICAL CONTROL

Vasopressin (0.2–0.4 U/min) used to be the most widely used agent to reduce portal blood pressure and control variceal bleeding. Adverse effects of vasopressin such as cardiac ischaemia (in about 10% of patients) and worsening coagulopathy (by release of plasminogen activator) have discouraged the use of this drug in recent years. Terlipressin, a triglycyl synthetic analogue of vasopressin, has a longer half-life and fewer cardiac side-effects and appears more effective and safe when used in combination with glyceryl trinitrate.22 Infusion of somatostatin and its analogue (octreotide, vapreotide) reduces portal blood pressure and azygous blood flow. They are safe and effective vasoactive agents to be used in acute variceal bleeding.23 The benefit is more prominent if these vasoactive agents are given early, even before endoscopy.22,24 Octreotide has also been shown to be effective when used as an adjuvant therapy in combination with endoscopic therapy.25 Recurrent bleeding episodes and hence requirement of transfusion are significantly reduced.

ENDOSCOPIC SCLEROTHERAPY

Endoscopic injection sclerotherapy is the mainstay of treatment. At endoscopy, sclerosants can be injected directly into the variceal columns (intravariceal injection) or into the mucosa adjacent to the varices (paravariceal injection) to cause venous thrombosis and inflammation, and tissue fibrosis. Commonly used sclerosants are ethanolamine oleate, sodium tetradecyl sulphate (1–3%), polidocanol and ethyl alcohol. None has appreciable advantage over the others and the choice is very much a personal preference of the endoscopist, and depends also on availability. Endoscopic sclerotherapy controls 80–90% of acute variceal bleeding. Complications such as ulcer formation, fever, chest pain and mediastinitis are common. Bleeding from gastric varices is more difficult to control by injection sclerotherapy because of difficult access. Butylcyanoacrylate (Histoacryl) has recently been used for gastric variceal injections, with a claimed superior haemostatic effect. It is mixed with lipiodol to delay the rate of polymerisation and allow radiological monitoring of the injection.

ENDOSCOPIC VARICEAL LIGATION

Endoscopic variceal ligation was introduced in the late 1980s as a mechanical method to control bleeding from varices. Rubber bands mounted on the banding device at the tip of the endoscope are released to strangulate the bleeding varices. Numerous studies comparing endoscopic variceal ligation with endoscopic sclerotherapy showed that the technique is as effective as injection sclerotherapy in acute bleeding.9 Procedure-related complications are significantly fewer, as there is no tissue chemical irritation. An overtube to facilitate banding avoids aspiration during the procedure, but may result in serious oesophageal injury if used improperly. The tunnel vision produced by the banding device as originally designed restricts visibility, and thus makes the procedure technically difficult when bleeding is heavy. With the introduction of multiple banding devices which are loaded with 5–10 rubber bands, and the use of transparent caps, the problems of overtube injury and tunnel vision have been overcome. In many centres, endoscopic variceal ligation has replaced injection sclerotherapy as the first choice for variceal haemorrhage. Many have combined the two endoscopic treatments together in an attempt to improve the outcome. Existing data so far do not support this combined therapy to be better. Combined endoscopic therapy cannot be recommended.

TRANSJUGULAR INTRAHEPATIC PORTOSYSTEMIC SHUNT (TIPS)

Using a transjugular approach, a catheter is inserted into the hepatic vein, and advanced under fluoroscopic guidance into a branch of the portal vein.26 By means of a guidewire and dilators, a self-expandable metal stent is introduced to create an intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. In good hands, success can be achieved in over 90% of cases. This procedure significantly reduces portal blood pressure and thus bleeding from varices. Major complications include intra-abdominal haemorrhage and stent occlusion. Hepatic encephalopathy has been reported in 25–60% of patients. Nevertheless, this is an effective salvage treatment for uncontrolled variceal bleeding. Meta-analysis comparing TIPS with endoscopic therapy showed that the former has secure haemostasis but at the cost of increasing risk of hepatic encephalopathy.27

SURGERY

Surgical treatments for variceal bleeding include direct devascularisation of the lower oesophagus plus the proximal stomach and a variety of surgical shunts. The role of surgery has diminished since the advent of endoscopic treatment and TIPS.28 Surgery is now used as a second-line treatment, when bleeding continues or recurs after two sessions of injection sclerotherapy or banding ligation. Both staple transection of the oesophagus and portocaval shunt surgery are highly effective emergency measures. Despite successful control of bleeding, long-term survival is not significantly improved. Hepatic encephalopathy is one of the major complications of shunting operations. Expectations that the Warren distal splenorenal shunt will preserve antegrade portal flow and avoid accelerated deterioration of liver function have not been realised. The Warren shunt is technically more difficult, especially if performed as an emergency. Choice of surgery should be carefully made in those who are potential transplant candidates, as it may complicate subsequent surgery. A protocol to manage variceal bleeding is shown in Figure 36.2.

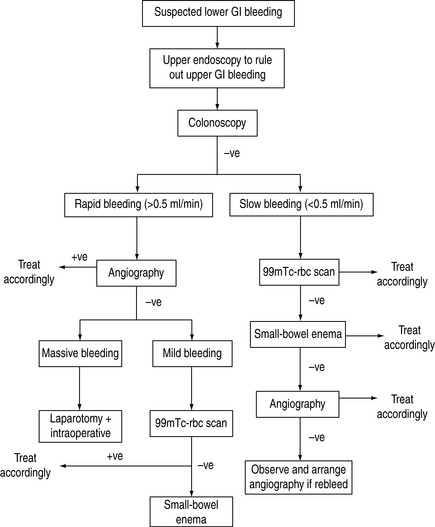

LOWER GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Haematochezia (bright-red blood) is the most common presentation of lower GI bleeding. However, bleeding from small intestine and right colon may also present as melaena. Abdominal pain preceding a massive bleeding episode suggests either ischaemia or inflammatory bowel disease. Painless massive bleeding is common in diverticulosis, angiodysplasia or from a Meckel’s diverticulum. In a patient with portal hypertension, haemorrhoids may present with massive haematochezia.

INVESTIGATIONS

ANGIOGRAPHY OR RADIONUCLIDE SCAN

Diagnostic angiography is helpful in two situations: (1) when the view of endoscopy is completely obscured by active haemorrhage; (2) in defining abnormal vasculatures, where angiography is more sensitive even if extravasation of contrast material is not seen. These lesions include angiodysplasia, arteriovenous malformation and various inherited vascular anomalies (e.g. Rendu–Osler–Weber syndrome, pseudoxanthoma elasticum and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome). Angiography may localise the site of bleeding in 80–85% of patients when the bleeding rate is more than 0.5 ml/min. Both superior and inferior mesenteric angiograms are often needed.

MANAGEMENT

ENDOSCOPY

Bleeding from vascular anomalies can be treated by electrocoagulation, heater probe and laser photocoagulation, unless the anomalies are too large or too diffuse. Bleeding colonic polyps can be removed by polypectomy or coagulated by hot biopsy forceps. Bleeding from colonic diverticula can also be controlled with thermocoagulation through colonoscopy.29

SURGERY

Diverticular bleeding usually arises from a relatively large vessel, and may be difficult to control with endoscopic or angiographic therapy. Partial resection of the colon is warranted after localisation of the bleeding site. Surgery is also indicated in vascular anomalies when endoscopic treatment fails. When an obvious and refractory massive lower GI bleeding is not identified by endoscopic or angiographic examinations, immediate laparotomy with possible subtotal colectomy should be offered. A protocol to manage lower GI bleeding is shown in Figure 36.3.

1 Silverstein FE, Gilbert DA, Tedesco FJ, et al. The national ASGE survey on upper gastrointestinal bleeding. I. Study design and baseline data. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27:73-79.

2 Silverstein FE, Gilbert DA, Tedesco FJ, et al. The national ASGE survey on upper gastrointestinal bleeding. II. Clinical prognostic factors. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27:80-93.

3 Holman RA, Davis M, Gough KR, et al. Value of a centralised approach in the management of haematemesis and melaena: experience in a district general hospital. Gut. 1990;31:504-508.

4 Lau JYW, Sung JJY, Lee KKC, et al. A comparison of high-dose omeprazole infusion to placebo after endoscopic hemostasis to bleeding peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:310-316.

5 Lau JY, Sung JJ, Lee KK, et al. Effect of intravenous omeprazole on recurrent bleeding after endoscopic treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers [see comment]. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:310-316.

6 Chung SS, Lau JY, Sung JJ, et al. Randomised comparison between adrenaline injection alone and adrenaline injection plus heat probe treatment for actively bleeding ulcers [see comment]. Br Med J. 1997;314:1307-1311.

7 Sung JJY, Chan FKL, Lau JYW, et al. The effect of endoscopic therapy in patients receiving omeprazole for bleeding ulcers with nonbleeding visible vessels or adherent clots: a randomized comparison. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:237-243.

8 Sung JY, Chung SC, Low JM, et al. Systemic absorption of epinephrine after endoscopic submucosal injection in patients with bleeding peptic ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:20-22.

9 Laine L, Cook D. Endoscopic ligation compared with sclerotherapy for treatment of esophageal variceal bleeding. A meta-analysis [see comment]. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:280-287.

10 Chung IK, Ham JS, Kim HS, et al. Comparison of the hemostatic efficacy of the endoscopic hemoclip method with hypertonic saline-epinephrine injection and a combination of the two for the management of bleeding peptic ulcers. Gastrointestin Endosc. 1999;49:13-18.

11 Cipolletta L, Bianco MA, Marmo R, et al. Endoclips versus heater probe in preventing early recurrent bleeding from peptic ulcer: a prospective and randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:147-151.

12 Lau JY, Sung JJ, Lam YH, et al. Endoscopic retreatment compared with surgery in patients with recurrent bleeding after initial endoscopic control of bleeding ulcers. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:751-756.

13 Sung JJY. Current management of peptic ulcer bleeding. Nature Clin Pract Gastro Hepatol. 2006;3:24-32.

14 Cook DJ, Fuller HD, Guyatt GH, et al. Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients. Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:377-381.

15 Tryba M. Sucralfate versus antacids or H2-antagonists for stress ulcer prophylaxis: a meta-analysis on efficacy and pneumonia rate. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:942-949.

16 Cook DJ, Witt LG, Cook RJ, et al. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in the critically ill: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 1991;91:519-527.

17 Zinner MJ, Zuidema GD, Smith P, et al. The prevention of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding in patients in an intensive care unit. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1981;153:214-220.

18 Tryba M. Risk of acute stress bleeding and nosocomial pneumonia in ventilated intensive care unit patients: sucralfate versus antacids. Am J Med. 1987;83:117-124.

19 Lam NP, Le PD, Crawford SY, et al. National survey of stress ulcer prophylaxis [see comment]. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:98-103.

20 Lasky MR, Metzler MH, Phillips JO. A prospective study of omeprazole suspension to prevent clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding from stress ulcers in mechanically ventilated trauma patients. J Trauma-Inj Infect Crit Care. 1998;44:527-533.

21 Messori A, Trippoli S, Vaiani M, et al. Bleeding and pneumonia in intensive care patients given ranitidine and sucralfate for prevention of stress ulcer: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br Med J. 2000;321:1103-1106.

22 Levacher S, Letoumelin P, Pateron D, et al. Early administration of terlipressin plus glyceryl trinitrate to control active upper gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhotic patients. Lancet. 1995;346:865-868.

23 D’Amico G, Politi F, Morabito A, et al. Octreotide compared with placebo in a treatment strategy for early rebleeding in cirrhosis. A double blind, randomized pragmatic trial. Hepatology. 1998;28:1206-1214.

24 Avgerinos A, Nevens F, Raptis S, et al. Early administration of somatostatin and efficacy of sclerotherapy in acute oesophageal variceal bleeds: the European Acute Bleeding Oesophageal Variceal Episodes (ABOVE) randomised trial [see comment]. Lancet. 1997;350:1495-1499.

25 Sung JJ, Chung SC, Lai CW, et al. Octreotide infusion or emergency sclerotherapy for variceal haemorrhage. Lancet. 1993;342:637-641.

26 Rossle M, Haag K, Ochs A, et al. The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt procedure for variceal bleeding [see comment]. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:165-171.

27 Papatheodoridis GV, Goulis J, Leandro G, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt compared with endoscopic treatment for prevention of variceal rebleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 1999;30:612-622.

28 Bornman PC, Krige JE, Terblanche J. Management of oesophageal varices. Lancet. 1994;343:1079-1084.

29 Jensen DM, Machicado GA, Jutabha R, et al. Urgent colonoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of severe diverticular hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:78-82.