Chapter 614 Abnormalities of Pupil and Iris

Aniridia

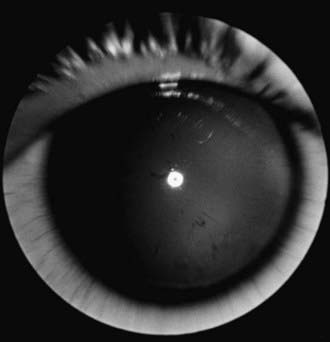

The term aniridia is a misnomer because iris tissue is usually present, although it is hypoplastic (Fig. 614-1). Two thirds of the cases are dominantly transmitted with a high degree of penetrance. The other 30% of cases are sporadic and are considered to be new mutations. The condition is bilateral in 98% of all patients, regardless of the means of transmission, and is found in approximately 1/50,000 persons.

Figure 614-1 Aniridia with minimal iris tissue.

(From Nelson LB, Spaeth GL, Nowinski TS, et al: Aniridia: a review, Surv Ophthalmol 28:621–642, 1984.)

Aniridia is caused by a defect in the PAX6 gene on chromosome 11p13. The PAX6 gene is the master control gene for eye morphogenesis. Aniridia can be sporadic or familial. The familial form is autosomal dominant with complete penetrance but variable expressivity. Sporadic aniridia is associated with Wilms tumor in as many as 30% of cases (Chapter 493.1). The combination of aniridia and Wilms tumor represents a contiguous gene syndrome in which the adjacent PAX6 and Wilms tumor (WT1) genes are both deleted. Some deletions create the WAGR complex of Wilms tumor, aniridia, genitourinary malformations, and mental retardation. All children with sporadic aniridia should undergo chromosomal deletional analysis to exclude the possibility of Wilms tumor formation. Children who test positive for the deletion should undergo repeated abdominal ultrasonographic and clinical examinations. Wilms tumor has also been reported in patients with familial aniridia. Therefore, these patients should also undergo chromosomal analysis.

Other Iris Lesions

The lesion of juvenile xanthogranuloma (nevoxanthoendothelioma) can occur in the eye as a yellowish fleshy mass or plaque of the iris. Spontaneous hyphema (blood in the anterior chamber), glaucoma, or a red eye with signs of uveitis may be associated. A search for the skin lesions of xanthogranuloma (Chapter 80.3) should be made in any infant or young child with spontaneous hyphema. In many cases, the ocular lesion responds to topical corticosteroid therapy.

Leukocoria

Leukocoria includes any white pupillary reflex, also called cat eye reflex. Primary diagnostic considerations in any child with leukocoria are cataract, persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous, cicatricial retinopathy of prematurity, retinal detachment and retinoschisis, larval granulomatosis, and retinoblastoma (Fig. 614-2). Also to be considered are endophthalmitis, organized vitreous hemorrhage, leukemic ophthalmopathy, exudative retinopathy (as in Coats disease), and less-common conditions such as medulloepithelioma, massive retinal gliosis, the retinal pseudotumor of Norrie disease, the pseudoglioma of the Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome, retinal dysplasia, and the retinal lesions of the phakomatoses. A white reflex might also be seen with fundus coloboma, large atrophic chorioretinal scars, and ectopic medullation of retinal nerve fibers. Leukocoria is an indication for prompt and thorough evaluation.

Frank JW, Kushner BJ, France TD. Paradoxic pupillary phenomenon: a review of patients with pupillary constriction to darkness. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106:1564-1566.

Greenwald MJ, Folk ER. Afferent pupillary defects in amblyopia. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1983;20:63-67.

Ivanov I, Shuper A, Shohat M, et al. Aniridia: recent achievements in paediatric practice. Eur J Pediatr. 1995;154:795-800.

Jaffe N, Cassady JR, Filler RM, et al. Heterochromia and Horner syndrome associated with cervical and mediastinal neuroblastoma. J Pediatr. 1975;87:75-77.

Jeffery AR, Ellis FJ, Repka MX, et al. Pediatric Horner syndrome. J Am Assoc Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1998;2:159-167.

Loewenfeld IE. “Simple, central” anisocoria: a common condition seldom recognized. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1977;83:832.

Mahoney NR, Liu GT, Menacker SJ, et al. Pediatric horner syndrome: etiologies and roles of imaging and urine studies to detect neuroblastoma and other responsible mass lesions. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:651-659.

Thompson HS. Segmental palsy of the iris sphincter in Adie’s syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:1615-1620.