Abdominal Hernia Reduction

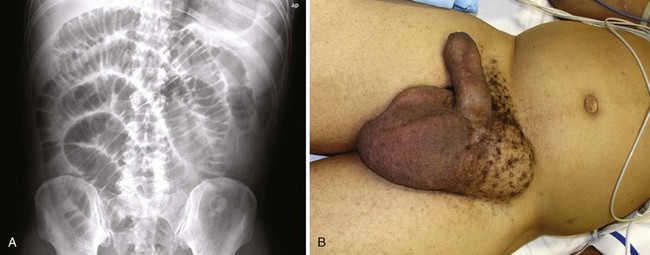

When a patient is seen in the emergency department (ED) with a suspected abdominal hernia, the emergency clinician must consider three issues: (1) Is a palpable mass truly a hernia? (2) Is the hernia easily reducible or incarcerated? (3) Is the vascular supply to the bowel strangulated? A patient with an easily reducible hernia can be discharged safely for outpatient follow-up and elective repair, whereas incarcerated and strangulated hernias are a surgical emergency. Some seemingly incarcerated hernias can be reduced by careful manipulation in the ED. Any patient with symptoms of bowel obstruction should also be evaluated for the possible presence of an abdominal hernia (Fig. 44-1).1

Hernias in the groin area have been the subject of medical diagnosis and treatment as long ago as 1550 bc. Throughout history, treatment of this condition has been the focus of ongoing discussion and debate.2–7 This chapter addresses abdominal and groin hernias, which are amenable to diagnosis and potential manual reduction in the ED. These types include ventral hernias of the abdominal wall, direct and indirect groin hernias, femoral hernias, and pantaloon hernias.

Background

A hernia is defined as protrusion of any viscus from its normal cavity through an abnormal opening. Abdominal hernias are characterized by protrusion of intraabdominal contents (usually bowel, with or without mesentery) through an abnormal defect in the abdominal wall musculature. Hernias can develop along a congenital tract that fails to close (e.g., indirect inguinal hernia) or along an area of weakness in the muscular and fascial wall layers (e.g., direct inguinal hernia or incisional hernia). This weakness may be due to aging and the accompanying loss of tissue elasticity, increased intraabdominal pressure, or trauma involving the abdominal wall itself. It is estimated that hernias develop in 5% of the male population and 2% of the female population8,9 and that 75% of them occur in the groin.10 In children and young adults, the majority of hernias are indirect inguinal hernias of congenital origin,11 whereas direct hernias are acquired and become more common as the patient ages.12

Classification

Indirect Inguinal Hernia

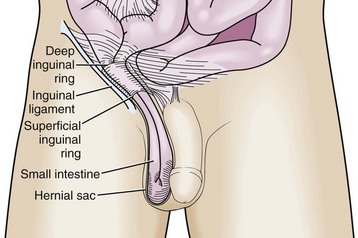

An indirect inguinal hernia passes through the internal (deep) inguinal ring and into the inguinal canal (Fig. 44-2). It is located lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels. During fetal development, the processus vaginalis allows descent of the testes into the scrotum. Failure of it to close before birth leads to a hernia or hydrocele.

Figure 44-2 Indirect inguinal hernia.

An indirect inguinal hernia is the most common type overall. This type of hernia occurs more frequently in males than in females and is commonly found in children and young adults. Approximately 5% of full-term infants and 30% of preterm infants will have an inguinal hernia.13,14 Incarceration occurs more commonly in patients younger than 1 year, and 30% of hernias in children younger than 3 months become incarcerated.15,16 For incarcerated inguinal hernias in children that are successfully reduced, surgical repair within 24 to 48 hours should be considered because of the risk for recurrent incarceration.17 When an inguinal hernia is diagnosed, even without incarceration or strangulation, it is important to make a referral for elective repair. Studies have shown that even asymptomatic and painless inguinal hernias can cause symptoms over time if they are not surgically repaired,4 although watchful waiting may also be appropriate in some patients.18 Clinical studies demonstrate increased morbidity with emergency versus elective repair of inguinal hernias.19

Direct Inguinal Hernia

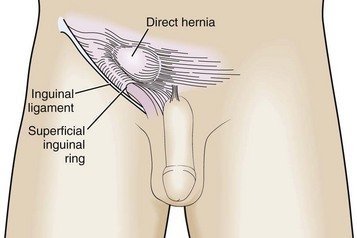

A direct inguinal hernia comes directly through the muscular and fascial wall of the abdomen. It is located within the inguinal triangle and is thus medial to the inferior epigastric vessels (Fig. 44-3). It can be differentiated from an indirect inguinal hernia in that it does not travel along the inguinal canal.

Figure 44-3 Direct inguinal hernia.

Femoral Hernia

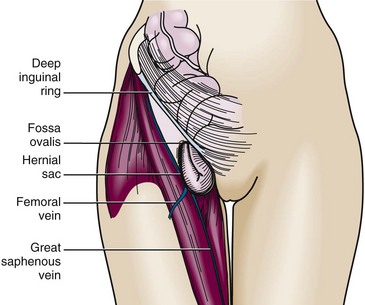

A femoral hernia occurs inferior to the inguinal ligament through a defect in the transversalis fascia. The contents protrude into the potential space in the femoral canal located medial to the femoral vein and lateral to the lacunar ligament (Fig. 44-4). Because of the small fascial defect and constriction by the inguinal ligament, this hernia becomes incarcerated in up to 45% of cases.20 A femoral hernia is relatively uncommon, occurs more frequently in women than in men, and is an uncommon condition in children.21

Figure 44-4 Femoral hernia.

Incisional Hernia

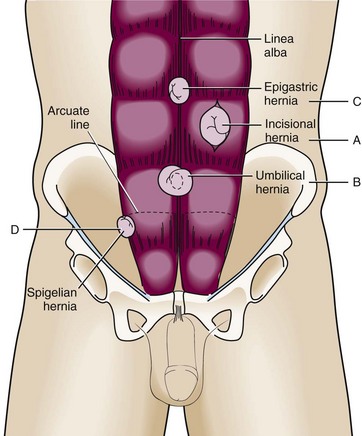

An incisional hernia commonly follows abdominal surgery in an area of postincisional weakness in the abdominal wall (Fig. 44-5A). Poor wound healing (e.g., because of infection) increases the likelihood of forming this type of hernia.22,23 An incisional hernia occurs after 3% to 13% of all abdominal surgeries and carries a recurrence rate of 20% to 50%.24 Because the lines of tension pull this hernia open, the size of the defect is usually sufficient to prevent incarceration.

Umbilical Hernia

An umbilical hernia traverses the fibromuscular ring of the umbilicus (Fig. 44-5B). This hernia is most commonly found in infants and children, is congenital in origin, and often resolves without treatment by the age of 5.25 If the hernia persists beyond this age, is larger than 2 cm, or becomes incarcerated or strangulated, it may be repaired surgically.19,26 An acquired umbilical hernia may also be seen in an adult, particularly with increased abdominal pressure (such as with obesity, ascites, or pregnancy). An umbilical hernia is more prone to incarceration and strangulation in an adult than in a child.

Epigastric Hernia

This hernia occurs in the midline through the linea alba of the rectus sheath (see Fig. 44-5C). It is usually located in the epigastric region between the xiphoid and the umbilicus. Though previously considered rare in infants, one study found epigastric hernias in 4% of all pediatric patients evaluated for hernias.27

Spigelian Hernia

A spigelian hernia is rare and courses through a defect in the lateral edge of the rectus muscle at the level of the semilunar line (Fig. 44-5D). It is caused by a partial abdominal wall defect in the transverse abdominal aponeurosis or the spigelian fascia. Patients are typically 40 to 70 years of age, but the hernia has also been reported in younger patients.1 Incarceration rates (often with omentum) have been reported to be as high as 20% with these uncommon hernias.25,28 Some reports suggest that ultrasound may be a valuable adjunct for the diagnosis of these hernias and may be helpful during attempted reduction procedures.29,30

Diagnosis

History and Physical Examination

An asymptomatic hernia may be manifested as a mass that is found incidentally on physical examination of the abdomen or groin. If a hernia is easily reducible, no specific intervention is required in the ED, but give patients instructions for appropriate outpatient surgical follow-up for potential elective repair. This is particularly important for inguinal hernias because elective repair is associated with much less morbidity than emergency repair for strangulation.4,19,20

Radiologic Imaging

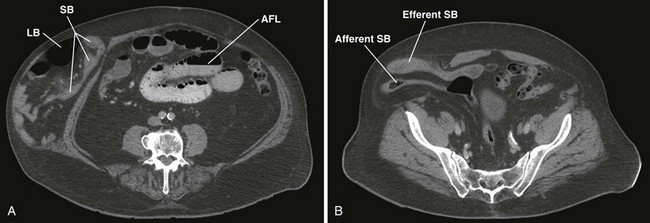

When findings on physical examination are equivocal and the emergency clinician suspects an occult hernia, several options are available for diagnostic imaging.31 Magnetic resonance imaging has a high positive predictive value for patients with clinically uncertain herniations,32 and computed tomography can also be helpful for the diagnosis of hernias and any associated complications (e.g., bowel obstruction or perforation)33 (Figs. 44-6 and 44-7). Ultrasound examination has been shown to have good sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of groin hernias34 and may decrease the rate of emergency surgery by improving the ability to reduce hernias.35 Ultrasound may also have good specificity and a high positive predictive value for diagnosing postoperative incisional hernias.31

Diagnosis of Incarcerated Versus Strangulated Hernias

In contrast, a strangulated hernia is a hernia in which the vascular supply to the herniated bowel is compromised, thus leading to ischemia. Strangulated hernias will most commonly also be incarcerated, but this is not a universal finding. Ischemic injury of the bowel is suggested by a red, purple, or bluish discoloration of the skin over the hernia, significant abdominal tenderness with peritoneal signs, and radiographic findings of extraluminal air.25 Patients with strangulated hernias may exhibit bowel obstruction, peritonitis, viscus perforation, intraabdominal abscess, or septic shock. Associated symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, fever, or abdominal distention.

In rare instances a strangulated or incarcerated hernia may inadvertently be reduced en masse to a preperitoneal location (Fig. 44-8), thus making the hernia sac and contents no longer palpable.36–38 In this case the hernia has not been reduced into the peritoneal cavity and the incarceration and ischemia have not been relieved. Because the clinician believes that the hernia has been appropriately reduced, this can result in delay in the diagnosis of incarcerated or ischemic bowel. Fortunately, this occurs in less than 1% of hernias.39 One case report described a 3-month-old patient whose gangrenous intestines were completely reduced into the peritoneal cavity (not the preperitoneal fat), thereby leading to delayed diagnosis and significant morbidity.40 Persistent pain after reduction of a hernia, especially more than at the orifice of the fascial defect, should alert the physician to the possibility of either properitoneal reduction or reduction of ischemic bowel.

Differential Diagnosis

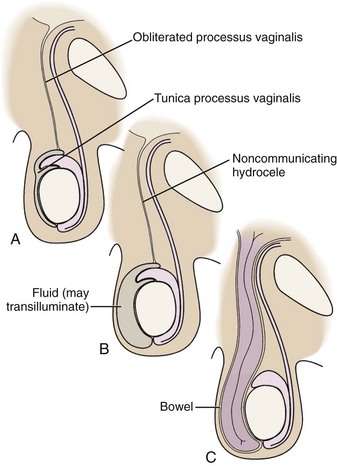

The differential diagnosis for a groin mass is large. Box 44-1 lists a number of disease processes that may masquerade as hernias. For example, testicular torsion can be mistaken for a hernia, especially if there is an associated reactive hydrocele. The clinician must examine the testicle for tenderness, swelling, lie, and cremasteric reflex. If there is concern for testicular torsion, urology should be notified immediately while diagnostic studies are undertaken simultaneously. A hydrocele can also be confused with a hernia because both can occupy the same anatomic space (Fig. 44-9). A hydrocele may transilluminate, whereas a hernia generally does not. Differentiation can be difficult and may require ultrasound to define the contents of the scrotum.

Reduction

Indications and Contraindications

The indications for reducing a hernia are the presence of a hernia and the absence of strangulation. Because many patients require sedation for successful reduction, it may be helpful to have a surgeon available while reduction is attempted and the patient is under sedation in the ED. This may be facilitated by discussing the treatment plan with the consultant before sedating the patient and attempting reduction. If reduction proves to be difficult, do not undertake repetitive attempts at reducing the hernia because this may increase the swelling and limit the chance of nonoperative reduction by the surgical consultant. An important prognostic factor for patients requiring surgical repair is the amount of time between the onset of symptoms and repair of an incarcerated hernia.7

Procedure

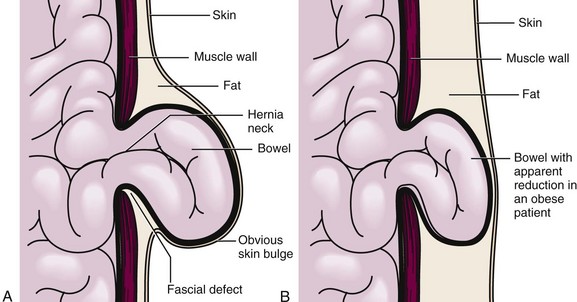

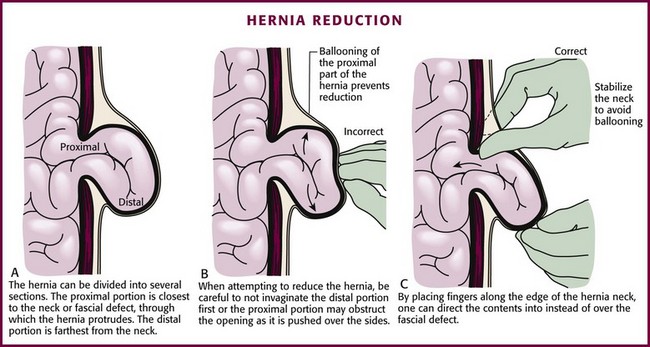

Begin the reduction procedure by gently guiding the proximal contents of the hernia sac back through the neck of the hernia first. In other words, reduce the hernia in the opposite order from which the contents protruded. Guiding the distal end of the contents or the hernia sac itself through the fascial defect first may cause the proximal contents to be displaced around the opening (ballooning) and prevent reduction. Apply gentle, steady pressure on the tissue at the neck of the hernia to overcome this problem and then gradually reduce the hernia (Figs. 44-10 and 44-11). Failure to perform this important procedure is a common error that precludes reduction.

Figure 44-11 Hernia reduction (see Fig. 44-10).

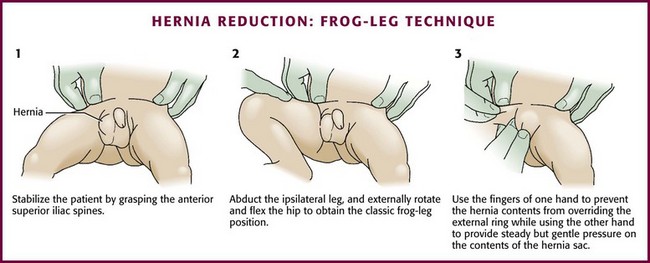

When attempting to reduce inguinal hernias in children, place the patient supine in about a 20-degree Trendelenburg position, which may allow spontaneous reduction. Another option is to place the patient in the “unilateral frog-leg” position41 (Fig. 44-12). Stabilize the patient by grasping the anterior superior iliac spines to prevent lateral movement of the pelvis. Abduct the ipsilateral leg, externally rotate and flex the hip, and flex the knee to obtain the classic frog-leg position. The purpose of this position is to allow the greatest reapproximation of both the internal and external rings. After achieving this position, use the fingers of one hand to prevent the hernia contents from overriding the external ring while using the other hand to provide steady but gentle pressure on the contents of the hernia sac. Repeated forceful attempts are not recommended.

Figure 44-12 Frog-leg technique of hernia reduction.

References

1. Vega, Y, Zequeira, J, Delgado, A, et al. Spigelian hernia in children: case report and literature review. Bol Asoc Med P R. 2010;102:62–64.

2. McClusky, DA, 3rd., Mirilas, P, Zoras, O, et al. Groin hernia: anatomical and surgical history. Arch Surg. 2006;141:1035–1042.

3. IPEG guidelines for inguinal hernia and hydrocele. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20:x–xiv.

4. Chung, L, Norrie, J, O’Dwyer, PJ. Long-term follow-up of patients with a painless inguinal hernia from a randomized clinical trial. Br J Surg. 2011;98:596–599.

5. Deeba, S, Purkayastha, S, Paraskevas, P, et al. Laparoscopic approach to incarcerated and strangulated inguinal hernias. JSLS. 2009;13:327–331.

6. Sarosi, GA, Wei, Y, Gibbs, JO, et al. A clinician’s guide to patient selection for watchful waiting management of inguinal hernia. Ann Surg. 2011;253:605–610.

7. Tanaka, N, Uchida, N, Ogihara, H, et al. Clinical study of inguinal and femoral incarcerated hernias. Surg Today. 2010;40:1144–1147.

8. Shochat, SJ. Inguinal hernias. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Arvin AM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1996:1116.

9. Zimmerman, LM, Anson, BJ. The Anatomy and Surgery of Hernia. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1953.

10. Kingsnorth, A, LeBlanc, K. Hernias: inguinal and incisional. Lancet. 2003;362:1561–1571.

11. Rosenthal, RA. Small-bowel disorders and abdominal wall hernia in the elderly patient. Surg Clin North Am. 1994;74:261–291.

12. Ponka, JL, Brush, BE. Experiences with the repair of groin hernia in 200 patients aged 70 or older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1974;22:18–24.

13. Harper, RG, Garcia, A, Sia, C. Inguinal hernia: a common problem of premature infants weighing 1,000 grams or less at birth. Pediatrics. 1975;56:112–115.

14. Harvey, MH, Johnstone, MJ, Fossard, DP. Inguinal herniotomy in children: a five year survey. Br J Surg. 1985;72:485–487.

15. Niedzielski, J, Kr, lR, Gawlowska, A. Could incarceration of inguinal hernia in children be prevented? Med Sci Monit. 2003;9:CR16–CR18.

16. Stylianos, S, Jacir, NN, Harris, BH. Incarceration of inguinal hernia in infants prior to elective repair. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:582–583.

17. Clarke, S. Pediatric inguinal hernia and hydrocele: an evidence-based review in the era of minimal access surgery. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20:305–309.

18. Leubner, KD, Chop, WM, Jr., Ewigman, B, et al. Clinical inquiries. What is the risk of bowel strangulation in an adult with an untreated inguinal hernia? J Fam Pract. 2007;56:1039–1041.

19. Alvarez, JA, Baldonedo, RF, Bear, IG, et al. Incarcerated groin hernias in adults: presentation and outcome. Hernia. 2004;8:121–126.

20. Gallegos, NC, Dawson, J, Jarvis, M, et al. Risk of strangulation in groin hernias. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1171–1173.

21. Wright, MF, Scollay, JM, McCabe, AJ, et al. Paediatric femoral hernia—the diagnostic challenge. Int J Surg. 2011;9:472–474.

22. Franz, MG. The biology of hernia formation. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:1–15. [vii].

23. Jin, J, Rosen, MJ. Laparoscopic versus open ventral hernia repair. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:1083–1100. [viii].

24. SSAT patient care guidelines. Surgical repair of incisional hernias. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1231–1232.

25. Salameh, JR. Primary and unusual abdominal wall hernias. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:45–60. [viii].

26. Chirdan, LB, Uba, AF, Kidmas, AT. Incarcerated umbilical hernia in children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2006;16:45–48.

27. Coats, RD, Helikson, MA, Burd, RS. Presentation and management of epigastric hernias in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:1754–1756.

28. Zacharakis, E, Papadopoulos, V, Ganidou, M. Incarcerated spigelian hernia: a case report. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12:CS64–CS66.

29. Torzilli, G, Del Fabbro, D, Felisi, R, et al. Ultrasound-guided reduction of an incarcerated Spigelian hernia. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2001;27:1133–1135.

30. Blaivas, M. Ultrasound-guided reduction of a spigelian hernia in a difficult case: an unusual use of bedside emergency ultrasonography. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:59–61.

31. den Hartog, D, Dur, AH, Kamphuis, AG, et al. Comparison of ultrasonography with computed tomography in the diagnosis of incisional hernias. Hernia. 2009;13:45–48.

32. van den Berg, JC, de Valois, JC, Go, PM, et al. Detection of groin hernia with physical examination, ultrasound, and MRI compared with laparoscopic findings. Invest Radiol. 1999;34:739–743.

33. Aguirre, DA, Santosa, AC, Casola, G, et al. Abdominal wall hernias: imaging features, complications, and diagnostic pitfalls at multi-detector row CT. Radiographics. 2005;25:1501–1520.

34. Djuric-Stefanovic, A, Saranovic, D, Ivanovic, A, et al. The accuracy of ultrasonography in classification of groin hernias according to the criteria of the unified classification system. Hernia. 2008;12:395–400.

35. Chen, SC, Lee, CC, Liu, YP, et al. Ultrasound may decrease the emergency surgery rate of incarcerated inguinal hernia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:721–724.

36. Olguner, M, Agartan, C, Akgur, FM, et al. Pediatric case of hernia reduction en masse. Pediatr Int. 2000;42:181–182.

37. Pearse, H. Strangulated hernia reduced en masse. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1931;53:822.

38. Wright, RN, Arensman, RM, Coughlin, TR, et al. Hernia reduction en masse. Am Surg. 1977;43:627–630.

39. Bowesman, C. Reduction of strangulated inguinal hernia. Lancet. 1951;1:1396–1397.

40. Strauch, ED, Voigt, RW, Hill, JL. Gangrenous intestine in a hernia can be reduced. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:919–920.

41. Fraser, GC. Reduction of an incarcerated hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:1519.