Chapter 9 Drug Discovery and Evaluation

Preclinical Process

Drug Discovery

Compound-Centered Drug Discovery

Natural Products

Naturally derived products were the first blockbuster drugs and paved the way for further drug discovery through compound-centered research. Once the efficacy and safety (and potential profitability) of compounds such as penicillin had been established, pharmaceutical chemists set about refining the structures of these agents to achieve specific pharmacologic effects. Table 9-1 lists some common drugs derived from natural sources.

| Compound | Source |

|---|---|

| Penicillin | Penicillium mold |

| Morphine | Opium poppy |

| Cyclosporine | Fungus |

Penicillin

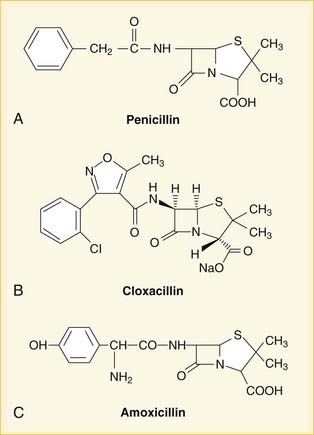

Once the chemical structure of penicillin was established, chemists began work on synthesizing new versions, each with its own distinct properties (Figure 9-1). Penicillin-resistant bacteria produce β-lactamase enzymes that attack the penicillin structure. A simple modification of the structure of penicillin created a bulky chemical chain that blocks β-lactamases from the β-lactam site, resulting in the β-lactamase–resistant drug cloxacillin.

Endogenous Ligands

Target-Centered Drug Discovery

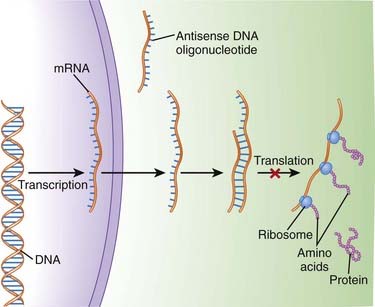

An understanding of the genetic basis for disease also provides new targets and will lead to gene-based therapies. The ultimate goal will be to selectively target genes that cause or contribute to disease, and prevent their expression. One of the most promising examples of this target-centered approach is antisense (Figure 9-3).

The sequences in mRNA are known as the “sense” strand, and when these sequences are known, a complementary “antisense” strand is designed to bind this sense strand in a sequence-specific manner. Once bound, the antisense strand prevents the mRNA from being translated into a protein.

The sequences in mRNA are known as the “sense” strand, and when these sequences are known, a complementary “antisense” strand is designed to bind this sense strand in a sequence-specific manner. Once bound, the antisense strand prevents the mRNA from being translated into a protein.

Second-generation antisense agents are designed to signal for destruction of the sense strand, once they have bound to it. The sense strand is destroyed by enzymes (RNAses), allowing the antisense strand to be used again.

Second-generation antisense agents are designed to signal for destruction of the sense strand, once they have bound to it. The sense strand is destroyed by enzymes (RNAses), allowing the antisense strand to be used again.

The newest generation of antisense is small interfering RNA (siRNA). These substances behave similarly to second-generation antisense, although they occur naturally in the body. Several siRNA agents are in clinical trials.

The newest generation of antisense is small interfering RNA (siRNA). These substances behave similarly to second-generation antisense, although they occur naturally in the body. Several siRNA agents are in clinical trials.The concept of gene-based therapeutics is covered in Chapter 6.

Tools Used in Drug Discovery

Combinatorial chemistry

Combinatorial chemistry

This is an automated method allows for the generation of a large number of compounds from a small number of precursors. This technology allows pharmaceutical companies to create very large libraries of compounds that systematically cover most or all of the possible variations in structure that may occur around a common precursor.

This is an automated method allows for the generation of a large number of compounds from a small number of precursors. This technology allows pharmaceutical companies to create very large libraries of compounds that systematically cover most or all of the possible variations in structure that may occur around a common precursor.Preclinical Testing

Pharmacokinetics

A key step in the development process is to determine the route of metabolism for the drug. If metabolized by CYP450 enzymes, the isoenzymes involved will be identified. Tests will also be performed to determine whether the drug is an inducer or inhibitor (or neither) of metabolizing enzymes, again with a focus on CYP450.

A key step in the development process is to determine the route of metabolism for the drug. If metabolized by CYP450 enzymes, the isoenzymes involved will be identified. Tests will also be performed to determine whether the drug is an inducer or inhibitor (or neither) of metabolizing enzymes, again with a focus on CYP450. Being an inhibitor or inducer of metabolizing enzymes is generally considered to be a weakness for a new drug, owing to the potential for drug interactions. Early tests can be performed on isolated enzymes in vitro, but in vivo testing will inevitably be performed to determine the effects of a drug in a whole animal.

Being an inhibitor or inducer of metabolizing enzymes is generally considered to be a weakness for a new drug, owing to the potential for drug interactions. Early tests can be performed on isolated enzymes in vitro, but in vivo testing will inevitably be performed to determine the effects of a drug in a whole animal.Toxicology

Tests for the toxic effects of a drug are generally performed on live animals, most commonly rats and mice. These tests are considered necessary because of the current limitations with using either in vitro testing or computer modeling to simulate the effects of a drug in a human.

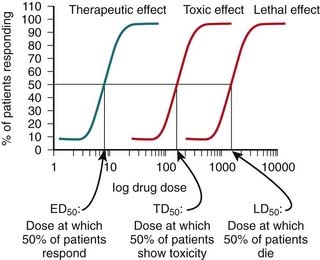

Tests for the toxic effects of a drug are generally performed on live animals, most commonly rats and mice. These tests are considered necessary because of the current limitations with using either in vitro testing or computer modeling to simulate the effects of a drug in a human. A key feature of these toxicology studies is that increasingly high, supraphysiologic doses of drug are administered. The therapeutic index of a drug is determined using quantal dose-response curves (see pharmacodynamics chapter for further description of quantal dose-response curves). The therapeutic index is the ratio of the toxic (TD) or lethal dose (LD) of a drug to its effective dose (ED) (Figure 9-4).

A key feature of these toxicology studies is that increasingly high, supraphysiologic doses of drug are administered. The therapeutic index of a drug is determined using quantal dose-response curves (see pharmacodynamics chapter for further description of quantal dose-response curves). The therapeutic index is the ratio of the toxic (TD) or lethal dose (LD) of a drug to its effective dose (ED) (Figure 9-4).Chemical and Pharmaceutical Development

Once the manufacturer has fully characterized the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and toxicology of the new chemical, the manufacturer must also consider practical issues, such as how the drug will be produced and what form it will take. The chapter on pharmacokinetics provides a complete description of various dosage forms. Typically, the oral route is the preferred route.

Once the manufacturer has fully characterized the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and toxicology of the new chemical, the manufacturer must also consider practical issues, such as how the drug will be produced and what form it will take. The chapter on pharmacokinetics provides a complete description of various dosage forms. Typically, the oral route is the preferred route. At this stage, the manufacturer will also get an idea of the cost of producing the new drug. Small molecules, which are simple chemical structures, are typically very inexpensive to produce, often pennies per tablet. At the other end of the spectrum are biologics, which require a much more sophisticated and expensive production procedure. Although not proportional, this increased cost of production is one of the reasons cited for the high price of biologic agents.

At this stage, the manufacturer will also get an idea of the cost of producing the new drug. Small molecules, which are simple chemical structures, are typically very inexpensive to produce, often pennies per tablet. At the other end of the spectrum are biologics, which require a much more sophisticated and expensive production procedure. Although not proportional, this increased cost of production is one of the reasons cited for the high price of biologic agents.Clinical Process

Stages in the Drug Approval Process

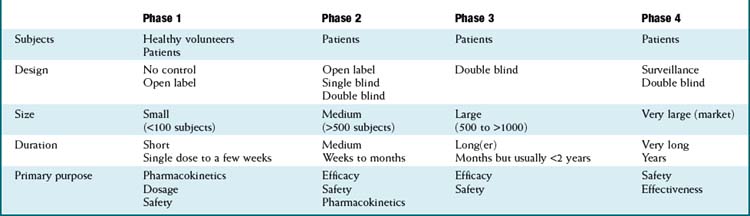

Once a new drug application has been filed, manufacturers may begin the process of clinical trials, with the overall goal of proving that the drug is both efficacious and safe. The process is traditionally carried out in phases, with increasingly large numbers of patients in each phase. The manufacturer is responsible for the conduct of these trials, although regulatory agencies may conduct site inspections to confirm that studies are being conducted properly. Table 9-2 lists the key characteristics of each phase of the clinical trial process.

Phase 1

Purpose: establish the pharmacokinetic profile of the drug. This includes the area under the curve (AUC) and the half-life (t1/2), as well as the metabolic routes of the drug.

Purpose: establish the pharmacokinetic profile of the drug. This includes the area under the curve (AUC) and the half-life (t1/2), as well as the metabolic routes of the drug. Until recently, this stage was primarily carried out in healthy (usually) male volunteers, because of (among other considerations) concerns over running experiments on sick individuals who might benefit from proven therapies. Males were preferred owing to liability issues from teratogens. Lately, especially in the case of serious diseases such as cancer, phase I trials have included patients as well, providing these individuals with an earlier (faster) exposure to promising new agents.

Until recently, this stage was primarily carried out in healthy (usually) male volunteers, because of (among other considerations) concerns over running experiments on sick individuals who might benefit from proven therapies. Males were preferred owing to liability issues from teratogens. Lately, especially in the case of serious diseases such as cancer, phase I trials have included patients as well, providing these individuals with an earlier (faster) exposure to promising new agents.Phase 2

In phase 2 we begin to see the drug compared with results in a control group, usually a placebo control. These trials include patients and are of moderate size, usually 100 subjects per group or less. By this time, a range of doses should be established, such that the main purpose is to determine efficacy and safety.

In phase 2 we begin to see the drug compared with results in a control group, usually a placebo control. These trials include patients and are of moderate size, usually 100 subjects per group or less. By this time, a range of doses should be established, such that the main purpose is to determine efficacy and safety.Phase 3

Phase 3 represents the final stage before drug approval and establishes the efficacy of the doses that will be used in the clinic. By this time, obvious safety issues should have been seen, so phase 3 trials are open to a much larger group of patients. However, owing to the size of these trials, less-obvious safety issues may arise, sometimes either preventing the approval of the drug or warranting a strong warning on the labeling.

Phase 3 represents the final stage before drug approval and establishes the efficacy of the doses that will be used in the clinic. By this time, obvious safety issues should have been seen, so phase 3 trials are open to a much larger group of patients. However, owing to the size of these trials, less-obvious safety issues may arise, sometimes either preventing the approval of the drug or warranting a strong warning on the labeling. Once a drug has successfully completed phase 3, the manufacturer can apply for a Notice of Compliance (NOC) from the FDA or equivalent regulatory agency. The FDA will review the efficacy and safety data then make a decision as to whether the drug should be approved for widespread use. Typically around 30 drugs receive an NOC each year in the United States.

Once a drug has successfully completed phase 3, the manufacturer can apply for a Notice of Compliance (NOC) from the FDA or equivalent regulatory agency. The FDA will review the efficacy and safety data then make a decision as to whether the drug should be approved for widespread use. Typically around 30 drugs receive an NOC each year in the United States.Phase IV

Phase 4 is also referred to as postmarketing surveillance. Regulatory agencies may require double-blind controlled trials in this phase, depending on how many unresolved issues remain from phase 3. Phase 4 has not been a regulatory requirement, although recent events with drugs such as rofecoxib have illustrated the importance of postmarketing surveillance.

Phase 4 is also referred to as postmarketing surveillance. Regulatory agencies may require double-blind controlled trials in this phase, depending on how many unresolved issues remain from phase 3. Phase 4 has not been a regulatory requirement, although recent events with drugs such as rofecoxib have illustrated the importance of postmarketing surveillance.Limitations of the Drug Approval Process

Clinical trials are typically not large enough to reveal rare but serious adverse events that may become obvious once the drug is available to the general population.

Clinical trials are typically not large enough to reveal rare but serious adverse events that may become obvious once the drug is available to the general population. Clinical trials are typically of too short a duration to reveal serious adverse effects that may take years of continual use to develop.

Clinical trials are typically of too short a duration to reveal serious adverse effects that may take years of continual use to develop. Studies that follow ICH guidelines provide assurance to countries that are using data from these studies that they follow a set of standards.

Studies that follow ICH guidelines provide assurance to countries that are using data from these studies that they follow a set of standards.Clinical Trial Design

Randomization is a process by which study participants are randomly assigned to one of the interventions in the trial.

Randomization is a process by which study participants are randomly assigned to one of the interventions in the trial.

One of the goals of randomization is to stratify groups in the trial so that the composition of each intervention group is identical to that of the other. Demographic and relevant baseline characteristics of the participant’s medical condition should be balanced to ensure that comparison groups all begin from the same starting point.

One of the goals of randomization is to stratify groups in the trial so that the composition of each intervention group is identical to that of the other. Demographic and relevant baseline characteristics of the participant’s medical condition should be balanced to ensure that comparison groups all begin from the same starting point. It is also essential that randomization be carried out in a way that ensures that the identity of treatment allocation is not revealed to the investigators (physicians, nurses), the patients, or anyone directly involved in the trial.

It is also essential that randomization be carried out in a way that ensures that the identity of treatment allocation is not revealed to the investigators (physicians, nurses), the patients, or anyone directly involved in the trial. Ideally, to maintain allocation concealment, randomization should be carried out by a third party; an automated interactive voice response system (IVRS) is typically used for this purpose. With an IVRS, the patient interacts with a computer (typically over the phone), and the computer randomizes the patient to a treatment group, assigning the patient a number.

Ideally, to maintain allocation concealment, randomization should be carried out by a third party; an automated interactive voice response system (IVRS) is typically used for this purpose. With an IVRS, the patient interacts with a computer (typically over the phone), and the computer randomizes the patient to a treatment group, assigning the patient a number. Blinding ensures that patients and providers are not influenced by knowledge of their assigned intervention.

Blinding ensures that patients and providers are not influenced by knowledge of their assigned intervention.

This is particularly important for subjective outcomes, such as quality-of-life scales, that rely on a patient’s own assessment of well-being. Patients who know they have been assigned to the placebo group, for example, may be less likely to believe they are benefiting from therapy.

This is particularly important for subjective outcomes, such as quality-of-life scales, that rely on a patient’s own assessment of well-being. Patients who know they have been assigned to the placebo group, for example, may be less likely to believe they are benefiting from therapy. Blinding should again be carried out in a way that ensures allocation concealment. The most important step in ensuring allocation concealment is to make sure all interventions are identical in appearance. Therefore the authors of a study should explicitly state that interventions were identical in appearance.

Blinding should again be carried out in a way that ensures allocation concealment. The most important step in ensuring allocation concealment is to make sure all interventions are identical in appearance. Therefore the authors of a study should explicitly state that interventions were identical in appearance. The simplest design is a superiority design, in which one intervention is determined simply to be statistically superior to another. Superiority designs typically involve a comparison with placebo.

The simplest design is a superiority design, in which one intervention is determined simply to be statistically superior to another. Superiority designs typically involve a comparison with placebo. In a noninferiority design, the goal is to confirm that a given intervention is not inferior to a comparator. Noninferiority trials are typically conducted between two active comparators.

In a noninferiority design, the goal is to confirm that a given intervention is not inferior to a comparator. Noninferiority trials are typically conducted between two active comparators. A margin for noninferiority is defined before the start of the trial.

A margin for noninferiority is defined before the start of the trial.

Analyzing Data from Clinical Trials

Efficacy Data

Subsequently, the ARR is expressed as a reciprocal, the number needed to treat (NNT). The NNT is the number of patients who must be treated with a given intervention to prevent an event in one patient.

Subsequently, the ARR is expressed as a reciprocal, the number needed to treat (NNT). The NNT is the number of patients who must be treated with a given intervention to prevent an event in one patient.

In the example, out of every 100 smokers who do not take statins, 10 will develop heart disease and 90 will not. Therefore the odds of developing heart disease in these patients are 10/90, or 0.11.

In the example, out of every 100 smokers who do not take statins, 10 will develop heart disease and 90 will not. Therefore the odds of developing heart disease in these patients are 10/90, or 0.11.Pooling Data from Studies: the Meta-Analysis

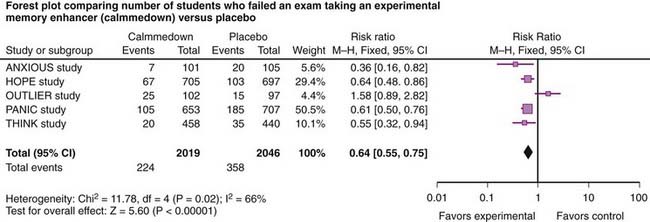

The data from a meta-analysis are often presented as a forest plot (Figure 9-5). The plot provides a quick graphical representation of the data, as well as numeric summaries to the left of the plot.

The plot gives a quick summary of the direction of the data. In this case, four of five studies favor the experimental drug over placebo, the only exception being the OUTLIER study.

The plot gives a quick summary of the direction of the data. In this case, four of five studies favor the experimental drug over placebo, the only exception being the OUTLIER study. The plot also provides an indication of the relative size of studies. The PANIC study has the largest point estimate (blue square) and is the largest study. The OUTLIER study is the smallest study.

The plot also provides an indication of the relative size of studies. The PANIC study has the largest point estimate (blue square) and is the largest study. The OUTLIER study is the smallest study. The horizontal line running through the point estimate gives an indication of the confidence interval, or the degree of variation within the study. Note that larger studies have less variation.

The horizontal line running through the point estimate gives an indication of the confidence interval, or the degree of variation within the study. Note that larger studies have less variation. Studies whose point estimate or confidence interval crosses unity (1 on the graph) show no statistical difference between comparison groups. In this case, all comparisons are statistically significant except OUTLIER.

Studies whose point estimate or confidence interval crosses unity (1 on the graph) show no statistical difference between comparison groups. In this case, all comparisons are statistically significant except OUTLIER. The plot also provides a summary point estimate, the final black diamond at the bottom. Again, if the black diamond does not cross unity, the results of the meta-analysis are statistically significant, in this case favoring the study drug.

The plot also provides a summary point estimate, the final black diamond at the bottom. Again, if the black diamond does not cross unity, the results of the meta-analysis are statistically significant, in this case favoring the study drug.The final key piece of information that a forest plot provides is an indication of the heterogeneity between studies. In Figure 9-5, the results of four studies are fairly consistent, with the exception of the OUTLIER study. An important consideration when assessing the reliability of these data is heterogeneity of the included studies.

The meta-analysis in Figure 9-5 also provides a measure of heterogeneity, expressed as either a P value or an I2 value. When the test for heterogeneity yields P < .05, significant heterogeneity is considered to exist within the meta-analysis. The higher the I2 value, the greater the heterogeneity. In this case, another analysis should be performed to account for this heterogeneity.

The meta-analysis in Figure 9-5 also provides a measure of heterogeneity, expressed as either a P value or an I2 value. When the test for heterogeneity yields P < .05, significant heterogeneity is considered to exist within the meta-analysis. The higher the I2 value, the greater the heterogeneity. In this case, another analysis should be performed to account for this heterogeneity.