Chapter 8.2 Interdisciplinary management of chronic pelvic pain A US physical medicine perspective

Introduction

As discussed in Chapter 8.1, historically, medical management of chronic pelvic pain (CPP) has frustrated both patients and providers, leading to the evolution of multimodal therapeutic strategies. Specialists are now viewing CPP as a polymorphic syndrome that may include organic pathology, musculoskeletal dysfunction, neuropathology and psychosocial impairments. Medical practice utilizing interdisciplinary, co-ordinated interventions is resulting in more successful treatment outcomes (Montenegro 2008).

• In addition to genital, anal, coccygeal, perineal, buttock and abdominal pain, CPP can include urinary symptoms such as dysuria, urinary urgency, frequency, hesitancy and poor stream strength.

• Bowel complaints include constipation, difficulty with evacuation, dyschezia and ‘pencil stool’ or varied, abnormal shapes of stool.

• Sexually, patients may experience anorgasmia or difficulty achieving orgasm, genital hyperarousal disorder, post-orgasmic pain, pain during or after intercourse, erectile dysfunction and/or excessive or lack of vaginal discharge in women.

Due to the varied symptoms, patients may seek the help of primary care physicians, gynaecologists, urologists, colorectal surgeons, orthopedists, neurologists and/or psychiatrists. It is reported that 85–90% of patients with CPP have musculoskeletal dysfunction (Tu et al. 2006, Butrick 2009) that has been identified as either a primary cause of pain and dysfunction or a secondary consequence of vulvodynia, painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis, chronic pelvic pain syndrome/non-bacterial chronic prostatitis, irritable bowel syndrome, pudendal neuralgia and endometriosis (Tu et al. 2006, Butrick 2009).

Furthermore, 30% of patients seen in primary care settings, and 85% in dedicated pain centres, are diagnosed with myofascial pain syndrome, demonstrating the importance of including musculoskeletal investigation early in the assessment of a patient with CPP (Butrick 2009). Ideally such investigation would be undertaken as part of a team approach to the condition.

Team management

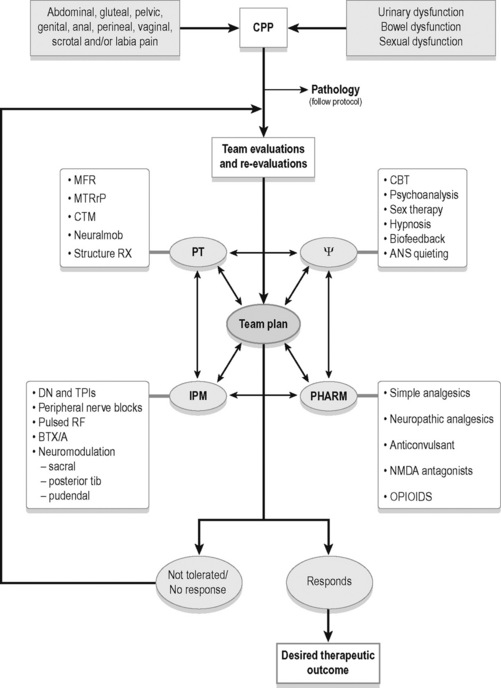

As in the UK, physicians, physical therapists and mental health providers in the US commonly form interdisciplinary teams working with chronic pain in general and CPP in particular (see Figure 8.2.1). Surgical interventions and invasive procedures run the risk of symptom exacerbation in patients with CPP, therefore conservative therapies such as manual physical therapy techniques, psychotherapies and pharmaceuticals are often utilized first to modulate pain. Simultaneously, organic pathology needs to be addressed if identified. Interventional medicine strategies have shown efficacy in treatment of CPP and should be utilized if conservative measures fail (Simons et al. 1999, Zhang et al. 2004, Maria et al. 2005, Amir et al. 2006). Numerous treatment options exist, and more than one medical professional may be able to treat particular pathophysiological features, whereas certain treatments may only be available from one team member. Treatment of CPP should be considered as a dynamic process with many possible effective treatment combinations. Certain treatments will be more or less important than others as a patient’s presentation changes.

As CPP is a syndrome associated with numerous pathophysiological features (see Box 8.2.1), extensive patient education and excellent interdisciplinary communication is imperative. Commonly, the treatment of a single impairment does not translate into the dramatic change the patient may expect. For example, if a patient with a 5-year history of severe vaginal burning is given an anticonvulsant and the pain is reduced, but not eradicated, the patient reports ‘disappointment’, and may think ‘it is not working’. In actuality, studies cited later in this chapter show anticonvulsants are effective for treating the central processing dysfunction this patient likely has. However, this patient may also present with pelvic floor myofascial trigger points and pudendal nerve inflammation, and until these impairments are also addressed, the overall syndrome is likely to persist. Through examinations, re-examinations, differential diagnoses and communication, the team can manage patient expectations more effectively.

The interventions listed in this text are effective treatments for the pathophysiological features listed in Box 8.2.1. The multimodal algorithm (see Figure 8.2.1) helps explain how to turn the complex problem of CPP into a sum of more manageable parts, expanding on the decision-making process to determine when and how to use different modalities. Clinical examples will be used to demonstrate the utility of the interdisciplinary approach.

Organic pathology intervention

Organic pathologies associated with CPP may include: yeast and bacterial infections, urinary tract, bladder and prostate infections, irritable bowel syndrome, endometriosis, colitis, Crohn’s disease, gastritis and sexually transmitted diseases. Symptoms of these pathologies mimic the symptoms of CPP and appropriate treatment protocols for the pathology should be followed (Butrick 2009).

Cognitive behavioural therapy

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) should be considered an important component in a comprehensive treatment plan for patients with CPP. Behavioural interventions for chronic pain have become commonly available alternatives to medical and rehabilitative therapies (Campbell & Mitchell 1996, Gatchel & Turk 1996). CBT has been shown to be an effective treatment for chronic pain patients, by helping to develop self-management skills to improve their personal control of their condition, reduce pain, distress, and pain behaviour, and improve daily functioning (Turk et al. 1983, Eccleston et al. 2009). Treatment that focuses on decreasing negative thinking, emotional responses to pain, and perceptions of disability, while increasing orientation toward self-management, are predictive of favourable treatment outcomes (Morely et al. 1999, McCracken & Turk 2002).

CBT has been shown to be efficacious for the treatment of vulvodynia in two uncontrolled studies (Abramov et al. 1994, Weijmar et al. 1996) and in one well-controlled, randomized study (Bergeron et al. 2008). Masheb et al. conducted a randomized trial to test the relative efficacy of CBT and supportive psychotherapy (SPT) in women with vulvodynia. The results suggest that psychosocial treatments for vulvodynia are well tolerated and produce clinically meaningful improvements in pain. They observed that CBT, relative to SPT, resulted in significantly greater improvements in pain severity and sexual function. Additionally, participants in the CBT condition reported significantly greater treatment improvement, satisfaction and credibility than in the SPT condition (Masheb et al. 2009).

Manual physical therapy intervention

The musculoskeletal impairments that may cause pelvic pain and dysfunction are connective tissue restrictions, muscle hypertonus with or without myofascial trigger points (including muscles of the pelvic floor, trunk and lower extremities), altered neurodynamics of peripheral nerves and pelvic girdle and biomechanical abnormalities. After a thorough history, an extensive physical examination is performed. The entire surface areas of the abdomen, trunk, thighs, pelvis (up to the base of the clitoris and penis including the labia and scrotum) should be examined for connective tissue restrictions (Fitzgerald 2009).

Conservative medical management starts with manual therapy to eradicate or modify the impairments, which may in turn, decrease pain. In 2009, the Urological Pelvic Pain Collaborative Research Network (UPPCRN) concluded that somatic abnormalities, including myofascial trigger points and connective tissue restrictions, were found to be very common in women and men with IC/PBS and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome, respectively (Fitzgerald et al. 2009).

Somatic abnormalities may be the primary abnormality in at least some patients and secondary in others, but in either situation they should be identified and treated. The UPPCRN also published the outcomes of their feasibility trial comparing connective tissue manipulation (CTM) and myofascial physical therapy, versus global therapeutic massage, in patients with CPP. The group receiving skilled CTM and myofascial therapy had a significantly higher response rate than the group receiving massage alone (Fitzgerald et al. 2009). See Chapter 11.2 for a summary of CTM methodology.

Altered neurodynamics

Compromised blood supply and/or neurobiomechanics of peripheral nerves may cause altered neurodynamics, thereby contributing to pelvic pain and dysfunction (Butler 2004). Connective tissue restrictions, muscle hypertonus and faulty joint mechanics can affect the dynamic protective mechanisms of peripheral nerves and lead to burning, stabbing, shooting pain in the territory of the nerve (Butler 2004).

For example, consider a patient with severe pelvic floor hypertonus. This patient may have inflammation around the pudendal nerve, secondary to compression by the muscles. Each time this patient attempts to have a bowel movement he is forced to strain, and several attempts are made before he succeeds at evacuating the stool. In addition to static compression causing inflammation, the muscles can fixate a normally mobile nerve as the patient forcefully lengthens the pelvic floor during straining. This can cause further neural irritation. The patient may experience shooting, stabbing rectal pain, either during or after the bowel movement, reflective of this neural irritation (Prendergast & Rummer 2008).

Treatment of altered neurodynamics involves removing the aggravating stimuli and restoring mobility. Myofascial treatment of connective tissue restrictions and muscle hypertonus may reduce aggravating neural input. Neural mobilization techniques to restore mobility along the path of the nerve have also shown efficacy (Ellis & Hing 2008).

Chapters 2, 9, 11, 12, 13 and 14 discuss the evaluation and treatment of the pelvic floor muscles, myofascial trigger points, biomechanics and the pelvic girdle at length.

Lifestyle modifications and home exercise programmes

All members of the interdisciplinary team can help the patient make temporary lifestyle modifications to improve function while the patient is being treated. Techniques to promote autonomic nervous system quieting, improve sleep hygiene, decrease stress, and improve diet and nutrition are all helpful, if not imperative, to the treatment process. Examples include the use of cushions, posture and/or breathing education, workstation, home and car modifications, clothing and footwear recommendations, and advice on exercise programme development (Prendergast & Rummer 2008).

Pharmacological therapy

The approach to pharmacological therapy for CPP in the USA is very similar to that in the UK. See Chapter 8.1.

Simple analgesics

Acetaminophen has both analgesic and antipyretic activity and has been used in acute and chronic painful conditions (Bannwarth & Pehourcq 2003); however, there is little evidence about its role in CPP. There is also very little evidence for the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in the treatment of CPP and even less for cyclo-oxygenase 2 (COX-2) selective drugs.

Neuropathic analgesics

Tricylic antidepressants are widely used for other chronic pain conditions such as fibromyalgia, chronic headaches, interstitial cystitis and irritable bowel syndrome. They have been studied for several pain disorders and have consistently shown benefit (Ohghena & Van Houdenhove 1992). The benefit of tricyclics is not generated by decreasing depression. If depression is present, it should be treated separately. Amitriptyline is the most commonly studied and has been shown to be an effective treatment for neuropathic pain, but side effects often limit its clinical use (Max 1994, Richeimer et al. 1997). A few studies have compared the use of amitriptyline versus placebo in patients with pelvic pain (McKay 1993). Some authors recommend it as the treatment of choice, whereas others have reported disappointing results (Richeimer et al. 1997, Rose & Kam 2002). Mixed reuptake inhibitors have been shown to be more effective than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of chronic pain (Fishbain et al. 2000, Yokogawa et al. 2002).

Anticonvulsants

Anticonvulsants have been used in pain management for many years. Gabapentin has been reported to be well tolerated and an effective treatment in various pain conditions, particularly in neuropathic pain (Beydoun et al. 1995, Rosenberg et al. 1997). Gabapentin failed to show effectiveness in genitourinary tract pain in some studies, but has shown success in the treatment of diabetic neuropathy, post-herpetic neuropathy, neuropathic pain associated with carcinoma, multiple sclerosis, genitourinary tract pain and vulvodynia in others (Ben & Friedman 1999, Sasaki et al. 2001). Sator-Katzenschlager et al. reported that after 6, 12 and 24 months, pain relief was significantly greater in patients receiving gabapentin either alone or in combination with amitriptyline than in patients on amitriptyline alone. In this study gabapentin was more effective than amitriptyline in improving neuropathic burning or spontaneous, paroxysmal pain (Sator-Katzenschlager et al. 2005). Pregabalin (Lyrica) is a relatively new drug that has been found to be very beneficial for patients with myofascial pain disorder and neuropathic symptoms, such as in fibromyalgia (Butrick 2009).

N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists

The N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor channel complex is known to be an important channel for the development and maintenance of chronic pain. NMDA antagonists have been useful in the management of neuropathic pain (Hewitt 2000). Ketamine has been beneficial in several chronic pain conditions including peripheral neuropathies, but its long-term role remains unclear (Visser & Schug 2006). Challenging pelvic pain conditions may be helped by ketamine if there is nerve injury or central sensitization.

Opioids

Opioids have a role in the management of chronic non-malignant pain, however, opioids in pelvic pain are poorly defined (McQuay 1999). The following guidelines for the use of opioids in chronic/non-acute urogenitial pain are (Fall et al. 2008):

• All other treatments must have been tried and failed;

• An appropriately trained specialist should consult with another physician when instigating opioid therapy;

• With a history or suspicion of drug abuse, psychological consultation is imperative;

• Patient should undergo a trial of opioids;

• Patient should be made aware of the rules and regulations of opioid use as well as the risk of addiction and dependency;

• Morphine is the first-line drug, unless there are contraindications to morphine or special indications for another drug.

Trigger point injection therapy

As described in Chapters 11 and 15, myofascial trigger points (MTrPs) are a nodular and hyperirritable area within a taut band of skeletal muscle. They can cause characteristic referred pain, local tenderness, autonomic phenomena, motor dysfunction and/or weakness and proprioceptive disturbances (Simons et al. 1999). Trigger points can be successfully treated with several approaches, one of which is trigger point injections. The most accepted theory hypothesizes that the mechanical disruption of the skeletal muscle fibres by an anaesthetic injection inactivates the trigger point (Simons 1999). Another possible mechanism is that the fluid injection may dilute nerve-sensitive substances that are present. Therefore, the injection may cause muscle fibre trauma releasing intracellular potassium, which can cause depolarization and block nerve fibres. A study looked at 18 women with pelvic pain for at least 6 months. All the women were found to have three to five trigger points in the pelvic floor muscles upon vaginal examination. Post trigger point injections, there was a significant decrease in a visual analogue scale, and improved patient global satisfaction and patient global cure visual scales (Langford et al. 2007). Trigger point injection therapy appears to be a viable treatment option for MTrPs in patients with CPP and should be considered when developing a comprehensive treatment plan.

Nerve blocks

Nerve blocks can be utilized for therapeutic and/or diagnostic purposes, however, interpreting a diagnostic block can be challenging given the many mechanisms by which a block acts. These mechanisms must be thoroughly understood as local anaesthetic agents are often utilized in nerve blocks. They primarily act by blocking sodium channels and can be effectively used for pain modulation at low doses that do not completely block nerve impulse propagation (Zhang et al. 2004, Amir et al. 2006). When managing neuropathic pain, sodium channels accumulate in the area of neural damage and develop abnormal discharge patterns at the periphery, and in the region of the dorsal root ganglia. Both the periphery and the dorsal root ganglia are sensitive to lidocaine (Ramer et al. 1999, Zhang et al. 2004, Amir et al. 2006). When neuropathic pain has become chronic, the mechanisms change over time resulting in several central and peripheral neural changes (Zhang et al. 2004). The reversal of these peripheral and central sensitizations or up-regulations would require the central nervous system to return to a more normal state, thus reducing pain (Abdi et al. 1998). It has been hypothesized that sodium channel blockade over an extended period can achieve this (Abdi et al. 1998). In addition to local anaesthetic, corticosteroids have also been used in the symptomatic relief of CPP (Antolak & Antolak 2009). The specifics on the techniques used, risks associated with, and the individual specialists performing neural blockades are available in various texts and will not be described here. The effectiveness of neural blockades for the treatment of the CPP population will be reviewed.

• Serial multilevel nerve blocks, including a caudal epidural, pudendal nerve block, and vestibular infiltration of local anaesthetic agents, may be an effective treatment for vulvar vestibulitis (Rapkin et al. 2008).

• A trans-sacrococcygeal approach to a ganglion impar block, for the management of chronic perineal pain may be an effective treatment (Toshniwal et al. 2007).

• Pudendal nerve blocks may be an effective tool for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in the management of pudendal-nerve-related pain and pelvic floor muscle hypertonus (Calvillo et al. 2000, McDonald & Spigos 2000, Kovacs et al. 2001, Hough et al. 2003).

• Peripheral nerve blocks, such as ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric/genitofemoral, may be an effective treatment for the management of neuropathic pain associated with nerve damage (Kennedy et al. 1994).

Botulinum toxin therapy

Botulinum toxin A (BTX/A) has been successfully used with myofascial pain and pain associated with chronic muscle spasm (Acquardo & Borodic 1994, Cheshire et al. 1994, Yue 1995, Porta et al. 1997). Initially it was thought that the mechanism of pain relief involved muscle relaxation induced by blockade of the release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction. Now it is also thought to involve the direct antinociceptive activity of blocking the release of local neurotransmitters involved in pain signalling as well as maintaining stimulation of local inflammatory mediators. This decrease in peripheral sensitization results in a secondary decrease in central sensitization by a direct reduction in neurotransmitter release in the dorsal horn (Aoki 2003). Additionally, there is a reduction in the release of substance P and glutamate within the dorsal horn (Porta 2000). It has been postulated that the relaxation of affected muscles by BTX/A should decompress entrapped nerves in patients with myofascial pain syndrome or pain from chronic muscle spasm and should facilitate physical therapy (Filippi et al. 1993, Rosalis et al. 1996). Physical therapy is imperative if maximum benefits are to be achieved with BTX/A. The effects of BTX/A are typically evident within 3–10 days and last for approximately 3 months (Porta 2000). The potential use of BTX/A in the treatment of CPP has been recognized for more than 10 years (Brin & Vapnek 1997). The literature presents recent evidence for utilizing BTX/A in successfully treating CPP conditions:

• BTX/A has been used with benefit for many pelvic floor hypertonic dysfunctions including vulvodynia, CPP, vaginismus, obstructed defecation, voiding dysfunction, urinary retention, perianal pain disorders and anal fissures (Maria et al. 2005).

• Ghazizadeh and Nikzad showed that 150–400 units of BTX/A resulted in a 75% response rate in women with vaginismus with no recurrence and a mean follow-up of 12 months (Ghazizadeh & Nikzad 2004).

• A double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled trial of BTX/A (80 units) versus physical therapy for CPP caused by levator spasm showed a statistically significant decrease in dyspareunia and non-menstral pain (Abbot et al. 2006).

• In a pilot study, Dykstra and Presthus showed a significant decrease in mean pain score, medication use and improved quality of life in women with provoked vestibulodynia with the use of BTX/A (35 units) (Dykstra & Presthus 2006).

• In 2007 Yoon et al. reported a marked improvement in subjective pain score following treatment with BTX/A (20–40 units) in a group of seven women with intractable genital pain (Yoon et al. 2007).

• A pilot study of 12 women with CPP for more than 2 years were treated with 40 units of BTX/A into the puborectalis and pubococcygeus. The authors reported significant decreases in dyspareunia and dysmenorrhoea. Quality of life and sexual activity were also significantly improved (Jarvis et al. 2004).

• Bertolasi et al. treated 67 women with either lifelong vaginismus or secondary dyspareunia complicated by vulvar vestibulitis with 20 units of BTX/A. They documented 46–76% symptom reduction and a ‘cure’ rate of 20–46% (Bertolasi et al. 2006).

Pulsed radiofrequency

There are two types of radiofrequency used clinically: continuous radiofrequency (CRF) and pulsed radiofrequency (PRF). CRF ablation has been in use for over 25 years. It uses a constant output of high-frequency current and produces temperatures greater than 45°C, which is neuroablative (Racz & Ruiz-Lopez 2006). PRF, on the other hand, uses brief pulses of high-voltage electric current which pauses between pulses to allow heat to dissipate. This causes less nerve destruction since the temperature does not usually exceed 42°C (Racz & Ruiz-Lopez 2006). The exact mechanism of PRF is unknown (Sluijter et al. 1998), but the current hypothesis proposes that PRF acts by modulating pain perception rather than directly destroying neural tissue (Cahana et al. 2006). Current evidence suggests that PRF may be useful in treating refractory neuropathic conditions (Hammer & Menesse 1998, Robert et al. 1998, Munglani 1999, Mikeladeze et al. 2003, Shah & Racz 2003, Van Zundert et al. 2003a,b, 2007, Cahana et al. 2006, Abejon et al. 2007, Martin et al. 2007, Wu & Groner 2007). There has been one reported case study of successfully using PRF on the pudendal nerve for CPP (Rhame et al. 2009). See Chapter 16.

Neuromodulation

Sacral neuromodulation

The pelvic floor is controlled by a complex set of neural reflexes that can be modified through neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity is necessary for activities such as toilet training, but it can result in a disruption of neural reflexes that can cause pelvic floor dysfunction. Neuromodulation, typically of the sacral nerves, can correct this disruption of neural reflexes in approximately 60–75% of patients with urinary retention, urge incontinence and urinary frequency (Chartier-Kastler et al. 2008). Using sacral neuromodulation to treat voiding dysfunction has been studied for many years (Schmidt et al. 1979, Baskin & Tanagho 1992). Neuromodulation has also been used to successfully treat chronic pain conditions such as migraine headaches, back pain and idiopathic angina pectoris (Alo & Holsheimer 2002). Even though it is not typically indicated for pelvic pain, there have been reports of up to 50% resolution of CPP and 85% improvement in pain and quality of life for patients with interstitial cystitis (Peters 2002, Mayer & Howard 2008). The exact mechanism of pain relief by neuromodulation is not known. The treatment is partly based upon the gate control theory. This implies that activity in the large-diameter Aβ fibres inhibit transmission of pain signals to the brain (Alo & Holsheimer 2002). Specific examples in the literature show evidence of sacral neuromodulation as a treatment for pelvic pain:

• Maher et al. reported a significant reduction of pain scores in 15 patients with interstitial cystitis (Maher et al. 2001).

• Siegel et al. reported a 60% significant improvement in pelvic pain in ten patients at a median follow-up of 19 months (Siegel et al. 2001).

• Peters and Konstandt implanted 21 patients with interstitial cystitis and reported a marked to moderate improvement in pain after 15 months in 20 patients. They also noted a corresponding significant reduction in narcotic medication use for control of their pain (Peters & Konstandt 2004).

• Zabihi et al. used bilateral S2–S4 caudal epidural sacral neuromodulation for the treatment of CPP, painful bladder syndrome and interstitial cystitis. They reported that 42% reported more than 50% improvement in their urinary symptoms and their visual analogue pain score improved by 40% (Zabihi et al. 2008).

Posterior tibial nerve stimulation

Percutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) (intermittent stimulation of the S3 nerve) developed as a less-expensive alternative to sacral nerve root stimulation. The goal is to stimulate the tibial nerve via a fine needle electrode inserted into the lower, inner aspect of the leg, slightly cephalad to the medial malleolus. The needle electrode is then connected to an external pulse generator which delivers an adjustable electrical pulse that travels to the sacral plexus via the tibial nerve. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation is currently used to treat lower urinary tract dysfunction such as urge incontinence, urgency/frequency and non-obstructive retention (Stoller 1999, Klingler et al. 2000, Govier et al. 2001, van Balken et al. 2001). Until recently there were few studies that showed improvement in the CPP population with PTNS. Most recently, Kabay et al. conducted a randomized controlled prospective clinical trial to evaluate the clinical effect of PTNS in patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. They reported that after 12 weeks of treatment, the VAS (visual analogue scale) score for pain and the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index significantly improved (Kabay et al. 2009). Kim et al. showed that after 12 weeks of PTNS an objective response occurred in 60% of patients with CPP and 30% had an improvement of 25–50% in the VAS score for pain (Kim et al. 2007). Another study showed PTNS had a positive effect in 39% of 33 pelvic pain patients (van Balken et al. 2003).

Chronic/continuous pudendal nerve stimulation

Another alternative approach to nerve stimulation is chronic or continuous pudendal nerve stimulation (CPNS). Instead of placing the leads at the sacral nerve root, the lead is placed at the pudendal nerve using neurophysiological guidance (Peters et al. 2009). There are few published studies that report outcomes of CPNS. Peters et al. looked at 84 patients who had interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome or overactive bladder. Most of these patients had previously failed sacral neuromodulation. They reported a positive response, ≥50% improvement being achieved in 71.4% (Peters et al. 2009). Electrotherapy and hydrotherapy in the treatment of CPP are discussed further in Chapter 16.

Multimodal treatment algorithm (Figure 8.2.1)

Patients with CPP present with a wide range of symptoms, impairments, disability and syndrome chronicity. Unfortunately, in many cases the patient is also suffering from the neuropathological and psychological consequences of having chronic pain. Thorough evaluations will lead to the initiation of appropriate, individualized treatments. This collection of individual, impairment-based treatments will comprehensively form an effective treatment plan. Once a pelvic pain syndrome has been diagnosed, a multimodal treatment algorithm can be a useful tool to organize the different therapies, re-formulate treatments after re-evaluations, and provide alternatives for ineffectual or intolerable therapies (Figure 8.2.1).

The process starts with the identification of CPP, treating organ pathologies (if present), and introducing the patient to the interdisciplinary team concept. (Fig 8.2.1: top two boxes). The interdisciplinary team (Fig 8.2.1: centre circles) may consist of many providers in four general therapeutic domains: physical therapy, interventional pain management, pharmaceuticals and psychosocial services. As the relevant literature and this chapter describe, the patient will benefit from a physical therapy evaluation to identify somatic dysfunction. The severity and chronicity of the patient’s case will dictate which other therapies are initiated. If a provider suspects central sensitization, anxiety, depression, nutritional, diet and/or sleep issues, simultaneous referrals to the psychosocial domain and for pharmacotherapy management may be indicated and beneficial. Patients are often evaluated over several appointments to identify all pain generators, dysfunction and limiting factors to treatment plans.

The multidirectional arrows of the algorithm stress the interdependent relationships between the providers, treatments and desired therapeutic outcomes. Once a treatment plan has been initiated, each provider needs to think critically about the efficacy of the intended individual treatment for the impairment in question (Fig 8.2.1: upper boxes). When two patients have the same diagnosis under the umbrella of pelvic pain (i.e. vulvodynia, painful bladder syndrome, etc.), it is almost certain their objective findings and treatment plans will be quite different. For example, as mentioned in this text, BTX/A has shown efficacy for decreasing pelvic floor hypertonus, which is known to cause pelvic pain. Often ineffectually, practitioners have administered BOX/A to treat ‘CPP’. However, a patient may have pelvic pain and not necessarily pelvic floor hypertonus. Therefore, BTX/A is likely ineffectual for this patient. Conversely, myofascial trigger points in the adductors, rectus abdominis and gluteal muscles can also cause CPP. The introduction of manual therapy, dry needling or trigger point injections, to the involved muscles, is reasonable and may be helpful. BTX/A may decrease hypertonus and MTrP therapy may eradicate MTrPs. Since the diagnosis of ‘pelvic pain’ does not explain the source of the problem it is more practical to think of interventions as tools for impairments rather than treatments for ‘pelvic pain’. In other areas of medicine, batteries of tests and a history and physical lead to a diagnosis. The diagnosis then dictates treatment. As Figure 8.2.1 depicts, multiple impairments are causal of CPP. The algorithm demonstrates that it is not appropriate to apply a linear therapeutic approach to complex syndromes such as CPP.

The overall treatment plan comprises the sum of individual therapeutic modalities as seen in the algorithm. Providers need to think globally about the function of the patient, but also locally about the intended intervention. Examples of individual treatments include connective tissue manipulation to restricted tissues, manual trigger point therapy to myofascial trigger points, prescribing of a sleep aid, talk therapy for a patient to decrease anxiety or use of hypnosis for pain management (Fig 8.2.1: upper boxes).

Once a treatment is initiated, patients will either respond, not tolerate the intervention, tolerate the intervention but have no response (i.e. a decrease in or elimination of the impairments, not necessarily an immediate change in the pain and/or functional status of the patient), or they may tolerate the treatment but generally not comply with the treatment plan (missed appointments, failure to take or tolerate medications, non-compliance with necessary lifestyle modifications, etc.) (Fig 8.2.1: lowest circles).

Abbot J.A., Jarvis S.K., Lyons S.D., et al. Botulinum toxin type A for chronic painand pelvic floor spasm in women: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol.. 2006;108(4):915-923.

Abdi S., Lee D.H., Chung J.M., et al. The anti-allodynic effects of amitriptyline, gabapentic, and lidocaine in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Anesth. Analg.. 1998;87:1360-1366.

Abejon D., Garcia-del-Valle S., Fuentes M.L., et al. Pulsed radiofrequency in lumbar radicular pain: Clinical effects in various etiological groups. Pain Pract.. 2007;7:21-26.

Abramov L., Wolman I., David M.P., et al. Vaginismus: an important factor in the evaluation and management of vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest.. 1994;38(3):194-197.

Acquardo M., Borodic G. Treatmetn of myofascial pain with botulinum A toxin. Anesthesiology. 1994;80:705-706.

Alo K.M., Holsheimer J. New trends in neuromodulation for the management of neuropathic pain. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:690-703.

Amir R., Argoff C.E., Bennett G.J., et al. The role of sodium channels in chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain. J. Pain. 2006;7:S1-S29.

Antolak S.J., Antolak C.M. Therapeutic pudendal nerve blocks using corticosteroids cure pelvic pain after failure of sacral neurmodulation. Pain Med.. 2009(10):186-189.

Aoki K.R. Evidence for antinociceptive activity of botulinum toxin type A in pain management. Headache. 2003;43(Suppl. 1):S9-S15.

Bannwarth B., Pehourcq F. Pharmacologic basis for using paracetamol: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic issues. Drugs. 2003;63S(2):5-13. [French]

Baskin L.S., Tanagho E.A. Pelvic pain without pelvic organs. J. Urol.. 1992;147:683-686.

Ben D.B., Friedman M. Gabapentin therapy for vulvodynia. Anesth. Analg.. 1999;89:1459-1460.

Bergeron S., Khalife S., Glazer H.I., et al. Surgical and behavioral treatments for vestibulodynia: two-and-one-half year follow-up and predictors of outcome. Obstet. Gynecol.. 2008;111(1):159-166.

Bertolasi L., Bottanelli M., Graziottin A., et al. Dyspareunia, vaginismus, hyperactivity of the pelvic floor and botulin toxin: the neurologists role. G. Ital. Ostet. Ginecol.. 2006;28:264-268.

Beydoun A., Uthman B.M., Sackellares J.C., et al. Gabapentin: pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety. Clin. Neuropharmacol.. 1995;14:469-481.

Brin M.F., Vapnek J.M. Treatment of vaginismus with botulinum injections. Lancet. 1997;349:252-253.

Butler D. Mobilization of the Nervous System. NY: Churchill Livingstone; 2004.

Butrick C.W. Pelvic Floor Hypertonic Disorders: Identification and Management. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am.. 2009;36:707-722.

Cahana A., Van Zundert J., Macrea L., et al. Pulsed radiofrequency: Current clinical and biological literature available. Pain Med.. 2006;7:411-423.

Calvillo O., Skaribas I.M., Rockett C., et al. Computed tomography-guided pudendal nerve block. A new diagnostic approach to long-term anoperineal pain: a report of two cases. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med.. 2000;25(4):420-423.

Campbell J.N., Mitchell M.J. Pain treatment centers at a crossroads: A practical and conceptual reappraisal. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 1996.

Chartier-Kastler E. Sacral neuromodulation for treating the symptoms of overactive bladder syndrome and non-obstructive urinary retention: >10 years of clinical experience. BJU Int.. 2008;101(4):417-423.

Cheshire W.P., Abashian S.W., Mann J.D., et al. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of myofascial pain syndrome. Pain. 1994;59:65-69.

Dykstra K.K., Presthus J. Botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of provoked vestibulodynia. J. Reprod. Med.. 2006;51:467-470.

Eccleston C., Williams A., Morely S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. 2009;15(2):CD007407.

Ellis R.F., Hing W.A., et al. Neural mobilizations: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials with an anaylsis of therapetic efficacy. J. Man. Manip. Ther.. 2008;16(1):8-22.

Fall M., et al. EAU Guidelines on Chronic Pelvic Pain. Eur. Urol.. 2008. Aug 31 [Epub]

Filippi G.M., et al. Botulinum A toxin effects on rat jaw muscle spindles. Acta Oto-laryngol. (Stockh). 1993;113:400-404.

Fishbain D.A., Cutler R., Rosomoff H.L., et al. Evidence-based data from animal and human experimental studies on pain relief with antidepressants: a structured review. Pain Med.. 2000;1(4):310-316.

Fitzgerald M.P., Anderson R.U., Potts J., et al. Randomized feasibility trial of myofascial physical therapy for the treatment of urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes. J. Urol.. 2009;182:570-580.

Gatchel R.J., Turk D.C. Psychological treatments for pain. A practitioners handbook. New York: Guilford Press; 1996.

Ghazizadeh S., Nikzad M. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of refractory vaginismus. Obstet. Gynecol.. 2004;104(5 Pt 1):922-925.

Govier F.E., Litwiller S., Nitti V., et al. Percutaneous afferent neuromodulation for the refractory overactive bladder: results of a multicenter study. J. Urol.. 2001;165(3):1193-1198.

Hammer M., Menesse W. Principles and practice of radiofrequency neurolysis. Curr. Rev. Pain. 1998;2:267-278.

Hewitt D.J. The use of NMDA-receptor antagonists in the treatment of chronic pain. Clin. J. Pain. 2000;16(Suppl. 2):S73-S79.

Hough D.M., Wittenberg K.H., Pawlina W., et al. Chronic perineal pain caused by pudendal nerve entrapment: anatomy and CT-guided perineural injection technique. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol.. 2003;181(2):561-567.

Jarvis S., Abbott J.A., Lenart M.B., et al. Pilot study of botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of chronic pelvic pain associated with spasm of the levator ani muscles. Aust. N.Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol.. 2004;44:46-50.

Kabay S., Kabay S.C., Yucel M., et al. Efficiency of posterior tibial nerve stimulation in category IIIB chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain: a sham-controlled comparative study. Urol. Int.. 2009;83:33-38.

Kennedy E.M., Harms B.A., Starling J.R., et al. Absence of maladaptive neuronal plasticity after genitofemoral ilioinguinal neurectomy. Surgery. 1994;116(4):665-670.

Kim S.W., Paick J.S., Ku J.H., et al. Percutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation in patients with chronic pelvic pain: a preliminary study. Urol. Int.. 2007;78:58-62.

Klingler H.C., Pycha A., Schmidbauer J., et al. Use of peripheral neuromodulation of the S3 region for treatment of detrusor overactivity: a urodynamic-based study. Urology. 2000;56(5):766-771.

Kotarinos R. International Continence Society Annual Meeting. Myofascial findings in patients with chronic urologic pain syndromes. 2009.

Kovacs P., Gruber H., Piegger J., et al. New, simple, ultrasound-guided infiltration of the pudendal nerve: ultrasonographic technique. Dis. Colon Rectum.. 2001;44(9):1381-1385.

Langford C., Udvari Nagy S., Ghoniem G.M. Levator ani trigger point injections: an underutilized treatment for chronic pelvic pain. Neurourol. Urodyn.. 2007;26:59-62.

Maher C.F., Carey M.P., Dwyer P.L., et al. Percutaneous sacral nerve root neuromodulation for intractable interstitial cystitis. J. Urol.. 2001:884-886.

Maria G., Cadeddu F., Brisinda D., et al. Management of bladder, prostatic and pelvic floor disorders with botulinum neurotoxin. Curr. Med. Chem.. 2005;12(3):247-265.

Martin D.C., Willis M.L., Mullinax L.A., et al. Pulsed radiofrequency application in the treatment of chronic pain. Pain Pract.. 2007;7:21-25.

Masheb R.M., Kerns R.D., Lozano C., et al. A randomized clinical trial for women with vulvodynia: cognitive-behavioral therapy vs. supportive psychotherapy. Pain. 2009;141(1–2):8-9.

Max M.B. Antidepressants as analgesics. In: Fields H.I., Liebeskind J.C., editors. Progress in brain research and management. Seattle: IASP; 1994:229-246.

Mayer R.D., Howard F.M. Sacral nerve stimulation: neuromodulation for voiding dysfunction and pain. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5(1):107-113.

McCracken L., Turk D. Behavioral and cognitive-behavioral treatment for chronic pain: outcome, predictors of outcome, and treatment process. Spine. 2002;27(22):2564-2573.

McDonald J.S., Spigos D.G. Computed tomography-guided pudendal block for treatment of pelvic pain due to pudendal neuropathy. Obstet. Gynecol.. 2000;95(2):306-309.

McKay M. Dysesthetic (“essential”) vulvodynia treatment with amitriptyline. J. Reprod. Med.. 1993;38:9-13.

McQuay H. Opioids in pain management. Lancet. 1999;353(9171):2229-2232.

Mikeladeze G., Espinal R., Finnegan R., et al. Pulsed radiofrequency application in treatment of chronic zygapophyseal joint pain. Spine J.. 2003;3:360-362.

Montenegro M.L. Physical therapy in the management of women with chronic pelvic pain. Int. J. Clin. Pract.. 2008;62(2):263-269.

Morely S., Eccleston C., Williams A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behavior therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headaches. Pain. 1999;80:1-13.

Munglani R. The longer term effect of pulsed radiofrequency for neuropathic pain. Pain. 1999;80:437-439.

Ohghena P., Van Houdenhove B. Antidepressant-induced analgesia in chronic non-malignant pain: a meta-analysis of 39 placebo-controlled studies. Pain. 1992;49(2):205-219.

Peters K.M. Neuromodulation for the treatment of refractory interstitial cystitis. Rev. Urol.. 2002;4(Suppl. 1):S36-S43.

Peters K.M., Konstandt D. Sacral neuromodulation decreases narcotic requirements in refractory interstitial cystitis. BJU Int.. 2004;93:777-779.

Peters K.M., Killinger K.A., Boquslawski B.M., et al. Chronic pudendal neuromodulation: expanding available treatment option for refractory urologic symptoms. Neurourol. Urodyn.. 2009. Sept 28 [Epub]

Porta M. A comparative trial of botulinum toxin type A and methylprednisolone for the treatment of myofascial pain syndrome and pain from chronic muscle spasm. Pain. 2000;85(1–2):101-105.

Porta M., et al. Compartment botulinum toxin injections for myofascial pain relief. Dolor. 1997;12(Suppl. 1):42.

Prendergast S.A., Rummer E.H. De-mystifying pudendal neuralgia. Current Directions in Women’s Health, a division of the Canadian Physiotherapy Association; 2008. Fall

Racz G.B., Ruiz-Lopez R. Radiofrequency procedures. Pain Pract.. 2006;6:46-50.

Ramer M.S., Thompson S.W., McMahon S.B. Causes and consequences of sympathetic basket formation in dorsal root ganglia. Pain. 1999(Suppl. 6):S111-S120.

Rapkin A., McDonald J.S., Morgan M., et al. Multilevel local anesthetic nerve blockade for the treatment of vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.. 2008;198:41.e1-41.e5.

Rhame E., Levey K.A., Gharibo C.G. Successful treatment of refractory pudendal neuralgia with pulsed radiofrequency. Pain Physician. 2009;12:633-638.

Richeimer S.H., Bajwa Z.H., Kahraman S.S., et al. Utilization patterns of tricyclic antidepressants in a multidisciplinary pain clinic: a survey. Clin. J. Pain. 1997;13:324-329.

Robert R., Prat-Prada I.D., Labatt J.J., et al. Anatomic basis of chronic perineal pain: Role of the pudendal nerve. Surg. Radiol. Anat.. 1998;20:93-98.

Rosales R.L., Arimura K., Takenaga S., et al. Extrafusal and intrafusal muscle effects in experimental botulinum toxin-A injection. Muscle Nerve. 1996;19:488-496.

Rose M.A., Kam P.C. Gabapentin: pharmacology and its use in pain management. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:451-462.

Rosenberg J.M., Harrell C., Ristic H., et al. The effect of gabapentin on neuropathic pain. Clin. J. Pain. 1997;13:251-255.

Sasaki K., Smith C.P., Chuang Y.C., et al. Oral gabapentin (neurontin) treatment of refractory genitourinary tract pain. Tech. Urol.. 2001;7:47-49.

Sator-Katzenschlager S.M., Scharbert G., Kress H.G., et al. Chronic pelvic pain treated with gabapentin and amitriptyline: A randomized controlled pilot study. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr.. 2005;117(21–22):761-768.

Schmidt R.A., Bruschini H., Tanagho E.A. Urinary bladder and sphincter responses to stimulation of dorsal and ventral sacral roots. Invest. Urol.. 1979;16:300-304.

Seigel S., Paszkiewicz E., Kirkpatrick C., et al. Sacral nerve stimulation in patients with chronic intractable pelvic pain. J. Urol.. 2001;166:1742-1745.

Shah R.V., Racz G.B. Pulsed radiofrequency lesioning of the suprascapular nerve for the treatment of chronic shoulder pain. Pain Physician. 2003;6:503-506.

Simons D.G., Travell J.G., Simons L.S. Travell and Simons’ myofascial main and dysfunction: the trigger point manual, second ed. vol. 1. Baltimore: Lippincott William & Wilkins; 1999.

Sluijter M.E., Cosman E.R., Rittman W.B.II, et al. The effects of pulsed radiofrequency fields applied to dorsal root ganglion – a preliminary report. Pain Clin.. 1998;11:109-117.

Stoller M.L. Afferent nerve stimulation for pelvic floor dysfunction. Eur. Urol.. 1999;35(Suppl. 2):16.

Toshniwal G.R., Dureja G.P., Prashanth S.M. Transsacrococcygeal approach to ganglion impar block for management of chronic perineal pain: a prospective observational study. Pain Physician. 2007;10(6):70-71.

Tu F.F., As-Sanie S., Steege J.F. Prevalence of pelvic musculoskeletal disorders in a female chronic pelvic pain clinic. J. Reprod. Med.. 2006;51(3):185-189.

Turk D.C., Meichenbaum D., Genest M. Pain and behavioral medicine: A cognitive-behavioral perspective. New York: Guilford Press; 1983.

Van Balken M.R., Vandoninck V., Gisolf K.W., et al. Posterior tibial nerve stimulation as neuromodulative treatment of lower urinary tract dysfunction. J. Urol.. 2001;166:914-918.

Van Balken M.R., Vandoninck V., Messelink B.J., et al. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation as neuromodulative treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Eur. Urol.. 2003;43:158-163.

Van Zundert J., Lame I., Jansen J., et al. Percutaneous pulsed radiofrequency treatment of the cervical dorsal root ganglion in the treatment of chronic cervical pain syndromes: A clinical audit. Neuromodulation. 2003;6:6-14.

Van Zundert J., Brabant S., Van de Kelft E., et al. Pulsed radiofrequency treatment of the gasserian ganglion in patients with idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. Pain. 2003;104:449-452.

Van Zundert J., Patijn J., Kessels A., et al. Pulsed radiofrequency adjacent to the cervical dorsal root ganglion in chronic cervical radicular pain: A double blind sham controlled randomized clinical trial. Pain. 2007;127:173-182.

Visser E., Schug S.A. The role of ketamine in pain management. Biomed. Pharmacother.. 2006;60(7):341-348.

Weijmar Schultz W.C., Gianotten W.L., van der Meijden W.I., et al. Behavioral approach with or without surgical intervention to the vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: a prospective randomized and non-randomized study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol.. 1996;17(3):143-148.

Wu H., Groner J. Pulsed radiofrequency treatment of articular branches of the obturator and femoral nerves for the management of hip joint pain. Pain Pract.. 2007;7:341-344.

Yokogawa F., Kiuchi Y., Ishikawa Y., et al. An investigation of monoamine receptors involved in antinociceptvie effects of antidepressants. Anesth. Analg.. 2002;95(1):163-168.

Yoon H., Chung W.S., Shim B.S. Botulinum toxin A for the management of vulvodynia. Int. J. Impot. Res.. 2007;19:84-87.

Yue S.K. Initial experience in the use of botulinum toxin A for the treatment of myofascial related muscle dysfunctions (abstract). J. Musculoskelet. Pain. 1995;3(Suppl. 1):22.

Zabihi N., Mourtzinos A., Maher M.G., et al. Short-term results of bilateral S2–S4 sacral neuromodulation for the treatment of refractory interstitial cystitis, painful bladder syndrome, and chronic pelvic pain. Int. Urogynecol. J.. 2008;19:553-557.

Zhang J.M., Li H., Munir M.A. Decreasing sympathetic sprouting in pathologic sensory ganglia: a new mechanism for treating neuropathic pain using lidocaine. Pain. 2004;109:143-149.