Chapter 7. X-rays

The questions in this chapter cover a variety of appearances. In all questions interpretation of the X-ray will be needed. In many the probable diagnosis and a management plan will also be expected.

QUESTIONS

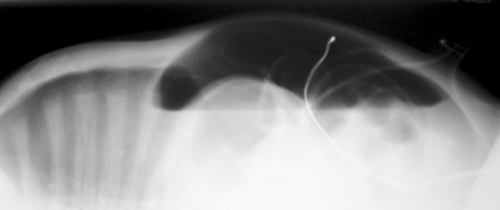

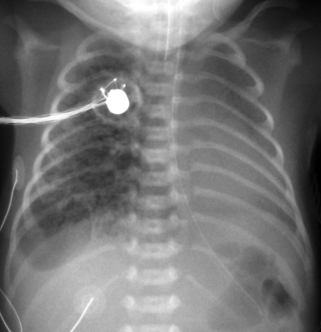

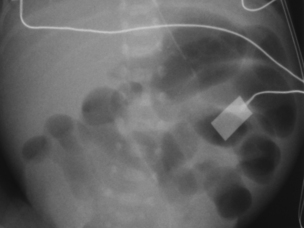

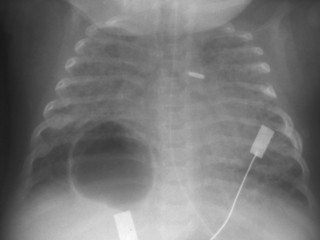

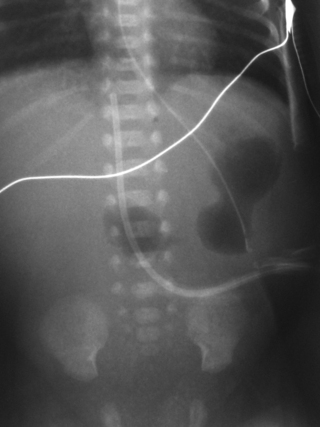

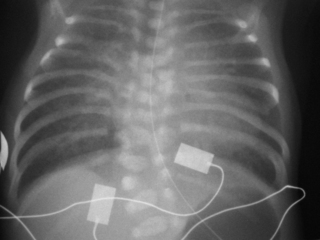

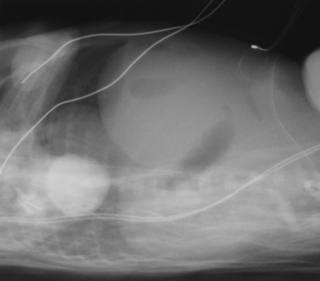

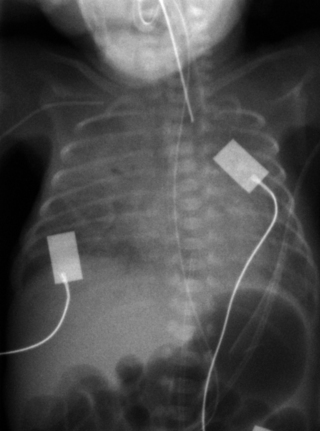

2. A 28 week baby is 10 days old. Abdominal distension has been noted and the following X-ray is obtained.

|

| Figure 7.2. |

a. Describe the abnormalities on the X-ray.

b. What is the diagnosis?

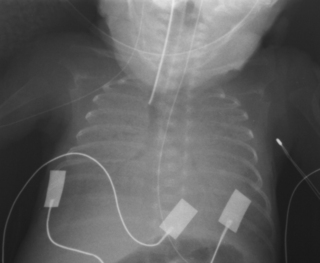

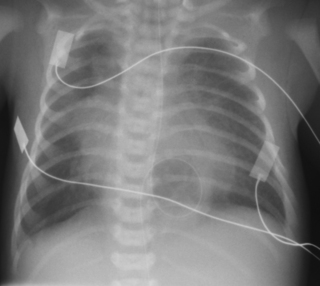

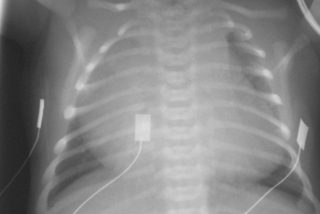

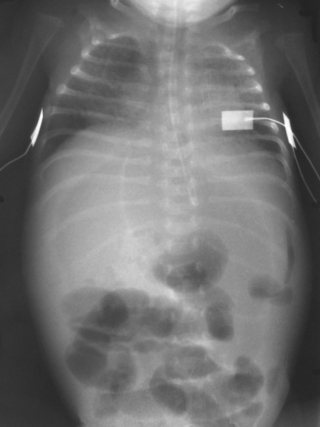

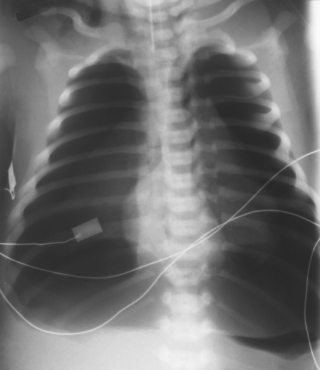

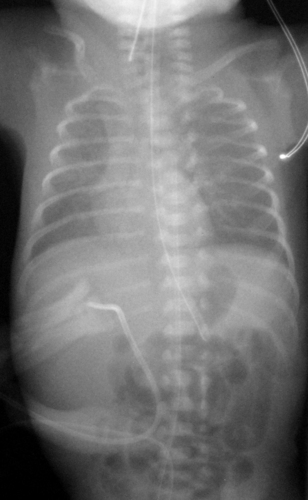

4. A 37 week gestation baby is noted to have frequent small vomits. At 24 hours of age he is noted to be tachypnoeic and he is admitted to the neonatal unit. A chest X-ray is obtained.

|

| Figure 7.4. |

a. Describe the abnormalities on the X-ray.

b. What are the diagnoses?

c. What is the management of the baby?

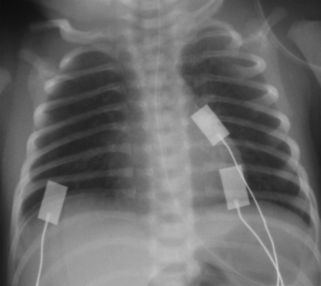

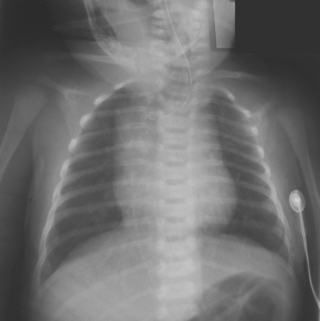

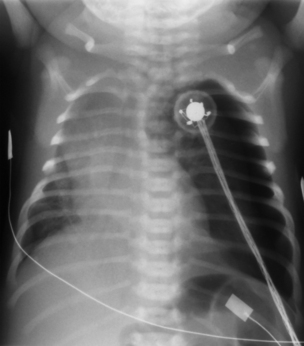

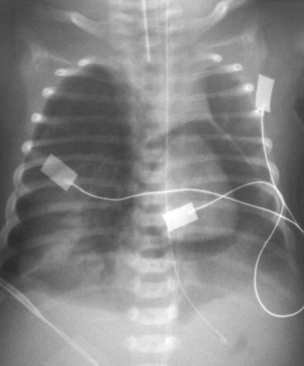

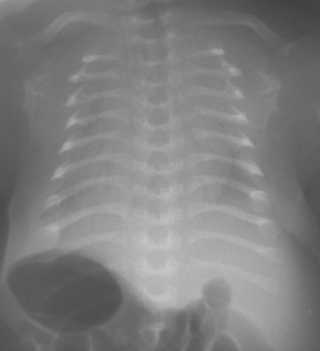

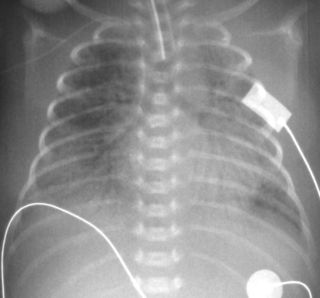

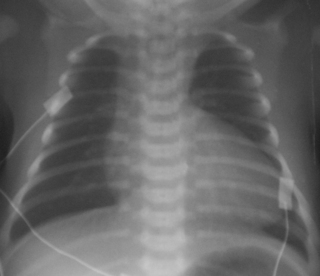

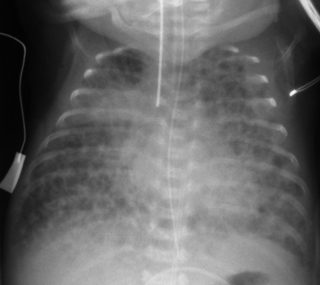

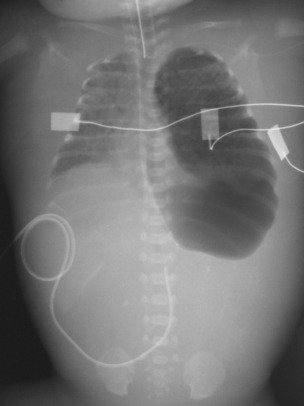

6. A 27 week infant is ventilated for RDS. Ventilatory requirements have increased over the last hour. A chest X-ray is obtained.

|

| Figure 7.6. |

a. Describe the abnormalities on the X-ray.

b. What is the management of the baby?

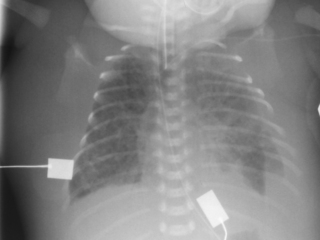

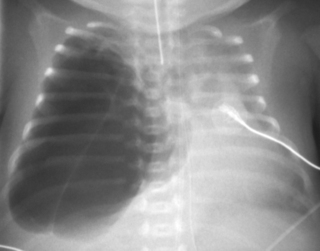

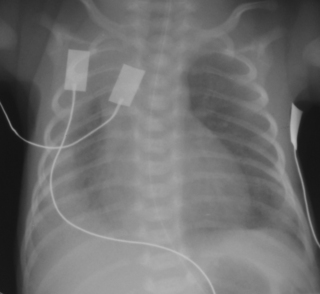

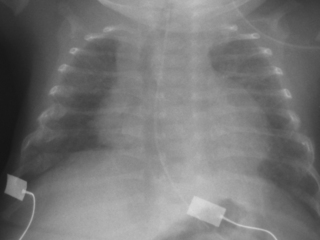

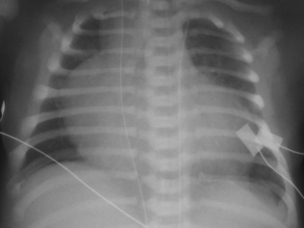

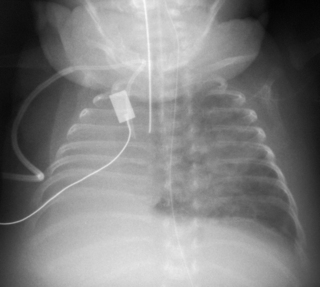

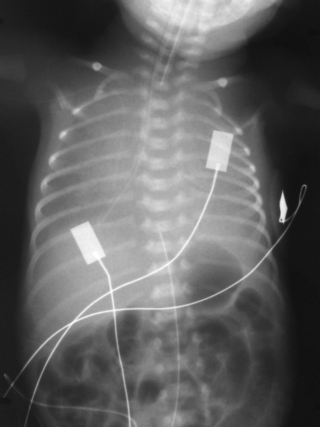

7. A term baby is noted to have a degree of frontal bossing, as does his mother. A chest X-ray is performed.

|

| Figure 7.7. |

a. Describe the abnormalities on the X-ray.

b. What is the diagnosis?

c. What is the inheritance of this condition?

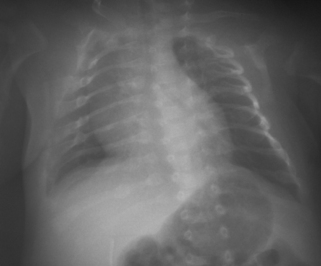

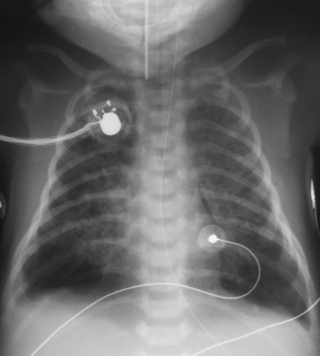

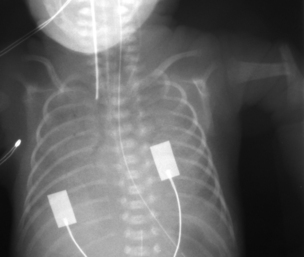

8. A 29 week gestation baby has been on CPAP for moderate respiratory distress and has been stable in 35% oxygen. He is active and has been noted to have quite marked intercostal recession on occasion. He suddenly deteriorates with persistent recession and an increase in oxygen requirements to 95%. A chest X-ray is taken.

|

| Figure 7.8. |

a. Describe the abnormalities on the X-ray.

b. What is the management of the baby?

9. A 27 week gestation infant is ventilated for respiratory distress. Ventilation requirements have been moderately high and two doses of surfactant have been given. Oxygen requirements have steadily risen from 55% to 95%. In response to a profound bradycardia and desaturation he receives ventilation down his endotracheal tube using a resuscitation bag. He deteriorates further and a chest X-ray is obtained.

|

| Figure 7.9. |

a. Describe the abnormalities on the X-ray.

b. What is the management of the baby?

10. A 31 week gestation infant is admitted to the intensive care unit. Mother booked late and there has been minimal antenatal care. The baby needs resuscitation at delivery and is transferred to the unit ventilated. Ventilation proves very difficult and a chest X-ray is obtained.

|

| Figure 7.10. |

a. Describe the abnormalities on the X-ray.

b. What is the differential diagnosis?

c. What is the management of the baby?

12. A term baby is thought to have an absent Moro reflex and limited movement of the arm. An X-ray is taken. In view of these changes a chest X-ray is then performed.

|

| Figure 7.12a. |

|

| Figure 7.12b. |

a. Describe the abnormalities on the arm X-ray.

b. Describe the abnormalities on the chest X-ray.

c. What is the most likely diagnosis?

d. What management would you consider?

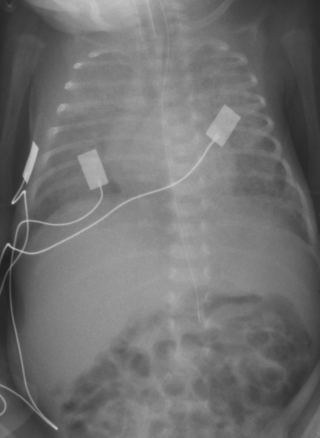

13. A 27 week gestation infant is now 4 weeks old. She needs 0.4 L/min supplementary oxygen but this has recently risen to 0.8 L/min. A chest X-ray is performed.

a. Describe the abnormalities on the X-ray.

b. What management has this baby had in the past that is clearly evident on the X-ray?

c. What management will you initiate in response to the abnormality on this chest X-ray?

|

| Figure 7.13. |

14. Antenatal ultrasounds have suggested a growth retarded fetus. At birth, the baby has obvious limb abnormalities and requires ventilation. Limb and chest X-rays are performed.

|

| Figure 7.14a. |

|

| Figure 7.14b. |

a. Describe the abnormalities on the limb X-ray.

b. Describe the abnormalities on the chest X-ray.

c. What is the most likely diagnosis?

d. What is the prognosis?

15. A baby is born at term and is noted to be cyanosed at rest. There is moderate recession. There is bilateral lower limb oedema. Femoral pulses are weak. The anterior fontanelle is bulging and a loud bruit can be heard when listening over it. A chest X-ray is performed.

|

| Figure 7.15. |

a. What abnormalities are there?

b. What possible explanation do you have?

c. What initial further investigations would you consider?

16. A baby is born at 26 weeks and requires ventilation from birth. Surfactant was given on delivery suite. Ventilation has steadily increased and the baby is in 95% oxygen at pressures of 28/6 at 24 hours of age. Blood gases are poor. A chest X-ray is performed.

|

| Figure 7.16. |

a. What abnormalities are there?

b. What is the most likely diagnosis?

c. What treatment would you consider?

17. A term infant is born following a severe asphyxial insult. There is thick meconium present and the oro-pharynx and trachea are suctioned under direct vision and meconium is removed. Ventilation is required and requirements steadily increase. At 8 hours of age the pressures are 32/4 and 100% oxygen is required. The blood gas shows a pH of 7.01, PO 2 of 3.4 and PCO 2 of 7.2.

|

| Figure 7.17. |

a. What does the X-ray show?

b. What is the diagnosis and what complication may be present?

c. What action could be taken?

18. A 36 week gestation infant has mild respiratory distress at birth. He requires 30% oxygen and there is mild recession. As symptoms persist an X-ray is performed at 6 hours of age.

a. What does the X-ray show?

b. If this is the only problem with the baby, what is the most likely diagnosis?

c. If the baby is asymptomatic, what should you do?

d. If the baby is symptomatic, what would you consider?

e. What other investigations would be warranted?

|

| Figure 7.18. |

19. A term infant is born by elective caesarean section because of previous caesarean sections. Shortly after birth the baby is noted to be mildly dusky and grunting and there is mild recession. A septic screen is performed and a chest X-ray obtained. Antibiotics are started.

|

| Figure 7.19. |

a. What abnormality is seen on this X-ray?

b. What is the most likely diagnosis?

c. What management steps do you need to take?

d. What is the prognosis for the baby?

21. A 26 week infant is in 0.5 L/min of supplementary oxygen at 36 weeks corrected age. He has mild recession and capillary gases show a fully compensated respiratory acidosis. A chest X-ray is taken as part of a work-up for chronic lung disease.

|

| Figure 7.21. |

a. Describe the X-ray.

b. What is the likely diagnosis?

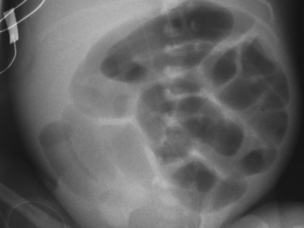

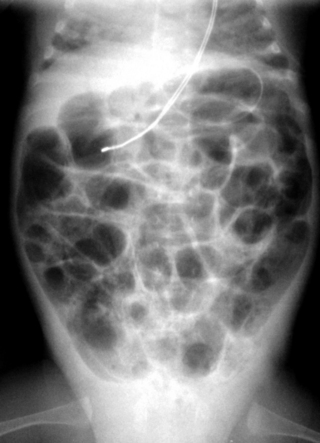

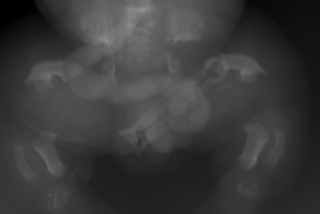

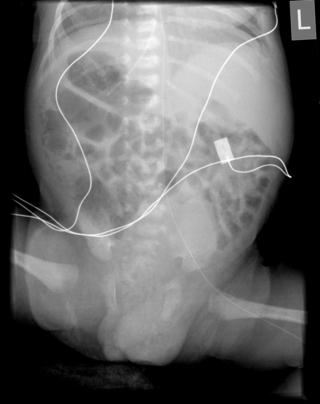

22. A baby born at 24 weeks gestation is 2 weeks old. He has been stable on low ventilation pressures but has not tolerated CPAP. Attempts have been made to start nasogastric feeds on several occasions but he does not appear to tolerate them as there are reasonable volume gastric aspirates on most occasions. Over the last 48 hours the aspirates have become increasingly bilious and an abdominal X-ray is taken.

a. Describe the X-ray abnormalities.

b. What is the diagnosis?

c. What is this diagnosis commonly associated with?

d. What is your immediate management plan?

e. What is the likely outcome for this baby?

|

| Figure 7.22. |

23. A 26 week infant has been ventilated for RDS. He was weaned onto CPAP after 16 days and was initially stable. Six days after starting CPAP his oxygen requirements started to rise (from 35% to 65%) and he was commenced on a course of dexamethasone; 36 hours after starting dexamethasone he deteriorates substantially. An X-ray is taken.

|

| Figure 7.23. |

a. What abnormalities are seen on this X-ray?

b. What is the diagnosis?

c. What is your management plan?

24. A term baby becomes cyanosed 6 hours after birth. Increasing the inspired oxygen concentration only partially treats this. On examination the chest is clear and there are no abnormal sounds. A chest X-ray is obtained.

|

| Figure 7.24. |

a. Describe the chest X-ray.

b. What is your diagnosis?

c. What will you do next?

26. A term infant is born to a mother who is known to have insulin dependent diabetes. He is grunting from birth and oxygen saturations are poor. A chest X-ray is obtained.

|

| Figure 7.26. |

a. Describe the X-ray.

b. What is your diagnosis?

c. What will you do next?

27. A 32 week gestation infant has been born. There has been a 10-week history of oligohydramnios. The baby has required ventilation from birth. Blood gases are poor at high ventilation pressures. A chest X-ray is taken at 3 hours of age.

|

| Figure 7.27. |

a. Describe the X-ray.

b. What is your diagnosis?

30. A 28 week gestation infant has been ventilated for 12 days. He is now 6 weeks old and requires 0.6 L/min of oxygen. A chest X-ray is taken.

|

| Figure 7.30. |

a. What does the X-ray show?

b. What action will you take?

31. A 25 week gestation infant has been ventilated since birth and is now 9 days old. A chest X-ray is taken.

|

| Figure 7.31. |

a. What does the X-ray show?

b. What is responsible for these changes?

33. A baby is born at 36 weeks to a mother with insulin dependent diabetes. He does not tolerate feeds and abdominal distension is noted. A chest and abdominal X-ray is taken at 36 hours of age.

|

| Figure 7.33. |

a. What does the X-ray show?

b. What do you think has happened?

c. What will you do next?

34. A term infant shows minimal respiratory effort and requires ventilation. A chest X-ray is taken. On talking to the parents you notice that the mother shows little expression in her facial movements.

|

| Figure 7.34. |

a. Describe the X-ray?

b. What do you think may be the explanation for these appearances?

c. What will you do?

35. A 25 week gestation infant has been ventilated since birth. Three doses of surfactant have been given with little effect. A chest X-ray is taken at 48 hours of age.

|

| Figure 7.35. |

a. What does the X-ray show?

37. A 24 week infant requires ventilation from birth and is now 4 weeks old. He is known to have duodenal atresia but the surgeons do not want to operate until he is a lot bigger. He has been to theatre for a surgical procedure. A chest X-ray is taken to check that the procedure has been performed correctly. The appearance of the right lung is as it has been since birth.

|

| Figure 7.37. |

a. What does the X-ray show?

b. What was the surgical procedure?

c. What is the explanation for the appearances of the right lung?

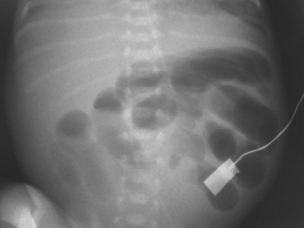

38. A 28 week gestation infant has been born and has needed relatively little ventilatory support. Feeds are introduced on day 3 and increased slowly. On day 5 he deteriorates and there is obvious abdominal distension. An X-ray is obtained.

|

| Figure 7.38. |

a. What does the X-ray show?

b. What do you think has happened?

c. What will you do next?

39. A term infant is born in poor condition following an ante-partum haemorrhage. The infant takes a few deep gasps and then stops breathing. Heart rate is 57 bpm. Bag and mask ventilation is commenced. There is poor chest movement and there is little response to ventilation. Transillumination is performed and there is no difference between the two sides. An endotracheal tube is inserted and ventilation does not improve. A butterfly needle is inserted into the right chest. A few bubbles are seen but this then stops. An X-ray is taken.

|

| Figure 7.39. |

a. What does the X-ray show?

b. How do you explain the clinical story?

c. What will you do next?

40. A 36 week gestation infant has been born and is in poor condition. She is very growth retarded and there is a widespread petechial rash. An X-ray is taken at 6 hours of age.

|

| Figure 7.40. |

a. What does the X-ray show?

b. How might these appearances link with the clinical history?

c. What treatment would you consider?

41. A 26 week gestation infant is 4 days old. A central venous line has been inserted into the left long saphenous vein and shortly afterwards abdominal distension is noted. An X-ray is performed.

a. List three major abnormalities in the intestines.

b. How is the position of the central line relevant?

c. What are the underlying diagnoses?

|

| Figure 7.41. |

42. A 26 week gestation infant has had severe RDS and has not responded well to surfactant. Because of deteriorating gases at high peak pressures high frequency oscillation is commenced. He initially improves and his inspired oxygen falls from 100% to 45%. After 24 hours he starts to deteriorate again and inspired oxygen increases to 90%. A chest X-ray is taken at 4 hours of age.

|

| Figure 7.42. |

43. A 27 week gestation infant has had moderate RDS and ventilation is weaning fairly rapidly. Extubation to CPAP is being considered when she deteriorates and abdominal distension is seen. NEC is suspected and a chest and abdominal X-ray is requested.

|

| Figure 7.43. |

a. What does the X-ray show?

b. What is the reason for her deterioration?

c. What action will you take?

44. A 26 week infant is born in poor condition and needs high pressure ventilation from the outset. The baby has caused considerable concern to the fetal medicine specialists and an intra-uterine procedure has been performed. A chest and abdominal X-ray is obtained shortly after birth.

|

| Figure 7.44. |

a. What does the X-ray show?

b. What intra-uterine procedure was performed?

c. What do you think the underlying diagnosis is?

45. A 28 week gestation infant has mild RDS. There was significant growth retardation and Dopplers showed reversed end-diastolic flow. The abdomen looks moderately distended and stage 1 NEC is suspected. A decision has been taken not to feed for at least for 10 days. A chest X-ray is obtained.

|

| Figure 7.45. |

a. What does the X-ray show?

b. What action will you take?

47. A 26 week gestation infant has required ventilation from birth. A chest and abdominal X-ray is taken at 4 hours of age.

|

| Figure 7.47. |

a. What does the X-ray show?

b. What action will you take?

48. A 25 week gestation infant has required ventilation from birth and has needed high pressures. She is now 2 weeks old and there has been a sudden deterioration. The cause is not obvious on examination and a chest and abdominal X-ray is requested.

a. What does the X-ray show?

b. Why was this not detected on examination?

c. What action will you take?

|

| Figure 7.48. |

50. A 29 week gestation infant deteriorates rapidly after birth and requires ventilation. A chest and abdominal X-ray is taken at 24 hours of age.

|

| Figure 7.50. |

a. What does the X-ray show?

b. What is the explanation?

c. What will you do next?

ANSWERS

1.

a.

i. The heart is displaced to the left of the chest.

ii. There are bowel loops visible in the chest cavity on the right.

b. Right-sided diaphragmatic hernia. These are much less common than left-sided diaphragmatic hernias. The baby is not ventilated (no endotracheal tube visible on CXR) and this therefore suggests that this defect was not recognised antenatally. The optimal management for these babies is intubation and ventilation immediately after birth avoiding lung inflation using a mask.

c. This baby should be ventilated to prevent the bowel from distending any more with swallowed air. A paediatric surgical opinion should be sought.

2.

a.

i. There is a nasogastric tube in situ.

ii. The bowel loops are dilated.

iii. The bowel wall is thickened.

iv. There is no air in the rectum.

v. There is widespread intramural gas.

b. The diagnosis is necrotising enterocolitis. There are staging criteria for NEC described by Bell. The features described in the above X-ray are consistent with Bell stage 2 NEC. 1

3.

a. The lateral abdominal X-ray shows free air. There are loops of bowel extending into the gas filled area.

b. The baby has a perforation. This would increase the stage of NEC to Bell stage 3.

c. The baby should be reviewed by a paediatric surgeon. If ventilation is compromised a drain should be inserted through the abdominal wall to release the pressure from build up of free gas in the abdomen. There have been recent studies to compare drain insertion with laparotomy for NEC. These have not demonstrated superiority of one technique over the other, but have confirmed the poor outlook of babies requiring surgery for perforated NEC. 2. and 3.

4.

a.

i. There is a large patch of opacification in the mid zone on the right side of the chest. There is some patchy shadowing elsewhere.

ii. There is a nasogastric tube in place.

iii. The nasogastric tube is coiled in a pouch in the thorax, behind the heart.

b. This baby has a sliding para-oesophageal (hiatus) hernia. The prevalence in newborns is unknown but it is thought to be relatively uncommon. It can be discovered on a routine X-ray but usually presents with features of gastro-oesophageal reflux. In this case the changes in the lung would be compatible with aspiration in association with reflux.

5.

a. With the exception of chest leads and a nasogastric tube there are no abnormalities on this X-ray. It is normal.

b. Normal.

c. The chest X-ray does not reveal anything that needs treatment.

6.

a.

i. The endotracheal tube is down the right main bronchus.

ii. The left lung is inadequately aerated.

iii. There is a nasogastric tube in situ.

b. The endotracheal tube should be withdrawn and the correct position confirmed with a repeat chest X-ray.

7.

a. The clavicles are absent.

b. Cleidocranial dysostosis. In this condition, the clavicle is either hypoplastic or absent and the ribs are short. The anterior fontanelle often closes late and there may be delayed eruption of teeth. There can be bossing of the forehead.

c. Autosomal dominant. It results from a mutation in the CBFA1 gene, which controls a key transcription factor in osteoblast differentiation.

8.

a.

i. Large tension pneumothorax on the left.

ii. Mediastinal shift to the right with tracheal deviation.

iii. Transcutaneous oxygen electrode on left upper chest.

iv. Surprisingly the infant is not intubated.

b.

i. Immediate drainage of the pneumothorax.

ii. Intubation and ventilation is very likely to be needed.

9.

a.

i. Intubated infant.

ii. Right pneumothorax.

iii. Pneumopericardium.

iv. Umbilical arterial catheter.

v. Bilateral hyperinflation of the chest.

vi. There is abnormal shadowing at the right base which is difficult to assess without other X-rays. This turned out to be a cystic adenomatoid malformation.

b. The pneumothorax should be drained. The decision to drain the pneumopericardium will be dictated by the clinical condition of the infant, specifically with respect to cardiac function.

10.

a.

i. Intubated infant.

ii. High UAC.

iii. Large cystic mass in right lung with a septum running across the middle.

b. These appearance would be consistent with a large cystic adenomatoid malformation (which was the case in this infant) or lobar emphysema. The latter is unlikely as this condition usually develops after birth as opposed to presenting with problems at birth. There is debate about the use of the word ‘congenital’ as some authorities maintain that the lobar emphysema develops as a result of airway problems that develop postnatally.

c. The management of these conditions is extremely difficult. Close co-operation with paediatric surgeons is essential. Direct puncture has a high chance of leading to formation of a broncho-pleural fistula. The infant may be too sick to tolerate thoracotomy, yet respiratory compromise may become so severe that intervention is necessary.

11.

a. There is a large bore (Replogle) nasogastric tube, partially coiled in the upper oesophagus. There is a shadow of air in the upper oesophagus but none lower down, suggesting an oesophageal atresia. There is evidence of gas in the gastrointestinal tract, suggesting a tracheo-oesophageal fistula.

b. Management is complex and requires close collaboration with paediatric surgeons. If the infant is mature and clinically stable, surgery should be considered in the relatively near future. If the infant is very sick or immature, then a decision may be made to defer surgery until a more stable state is achieved, or the baby has grown.

12.

a.

i. The X-ray shows a fracture of the left humerus.

ii. There is marked osteopenia of all bones, especially marked in the bones of the forearm.

b.

i. Marked rotation of the film.

ii. There is thinning of the ribs with what are almost certainly fractures with callous formation.

iii. Osteopenia of all bones.

c. Osteogenesis imperfecta.

d. Pamidronate infusions have been used to improve bone density and reduce the risk of further fractures. Such management should only be undertaken in specialist centres as general experience of this management is extremely limited.

13.

a.

i. Clip in left upper chest.

ii. Abnormal separation of left 4th and 5th ribs.

iii. Widespread patchy opacification of both lungs.

iv. Large bulla in right lung base.

v. Nasogastric tube in situ.

b. The PDA has been clipped.

c. None. This infant is not intubated and ventilated and unless there are signs of severe respiratory distress, no action is needed. The infant has what appears to be quite severe chronic lung disease and would not benefit from re-ventilation. Although the bulla looks fairly large on X-ray, it is only occupying a relatively small proportion of the intra-thoracic space. The majority resolve spontaneously over time, as was the case with this infant.

14.

a.

i. Short long bones (compare to size of cord clamp).

ii. Marked bowing of bones, particularly noticeable in femurs.

b. The chest is very narrow with abnormal ribs that are short and thin with splayed ends. The vertebral bodies are flattened with wide intervertebral spaces.

c. The appearance is that of a congenital skeletal dysplasia. In this case the most likely diagnosis is thanatophoric dysplasia as indicated by the extremely short limbs with classic ‘telephone receiver’ shaped femurs.

d. Thanatophoric dysplasia is invariably fatal, usually shortly after birth.

15.

a. The heart is grossly enlarged in all dimensions.

b. The enlarged heart does not in itself point to a specific diagnosis and conditions such as a cardiomyopathy, structural heart defect, storage disorder, maternal diabetes and heart failure are all possibilities. In this case the combination of a large heart, peripheral oedema and a bruit over the bulging anterior fontanelle should raise the possibility of an intracranial arteriovenous malformation resulting in high output cardiac failure (as was the case in this baby).

c.

i. Echocardiogram.

ii. Cranial ultrasound, CT scan or MRI.

iii. Four limb BP and oxygen saturations.

iv. Check maternal history and antenatal ultrasounds.

16.

a.

i. There is widespread opacification throughout both lung fields.

ii. There are clear air bronchograms on both sides.

iii. The heart border is not clearly defined.

iv. The costophrenic and cardiophrenic angles are not clearly visualised.

v. There is an endotracheal tube.

vi. There is a central venous line entering by the left arm and with a tip at the junction of the SVC and right atrium.

b. Respiratory distress syndrome is the most likely diagnosis.

c. Surfactant should be given if the dose has not been repeated since birth. Ventilatory requirements are high and some centres would consider high frequency oscillatory ventilation at this point. If this is not available ventilation will probably need to be adjusted to improve the blood gases.

17.

a.

i. There is patchy opacification that is most marked in the perihilar region.

ii. There are basal bullae, most apparent on the right.

iii. The lungs are relatively hyperexpanded, 11 posterior rib ends are showing.

iv. There is a transcutaneous oxygen electrode, chest leads and a nasogastric tube.

v. There is an endotracheal tube.

b. The history and chest X-ray appearances are typical of meconium aspiration syndrome. It is very possible that a significant degree of persistent pulmonary hypertension is contributing to the clinical picture.

c. There is evidence that both high frequency ventilation and nitric oxide may be useful in this condition, and are particularly useful in combination. In severe cases extracorporeal membrane oxygenation may be life saving and referral should be made early. There is some evidence from animal studies and limited human data to support the use of surfactant, either by bolus administration of by surfactant lavage.

18.

a.

i. There is a nasogastric tube in situ.

ii. There is loss of the costophrenic angle on the right and increased shadowing in the lower peripheral right chest.

b. Right pleural effusion. Pleural effusions can occur for many reasons. If diagnosed antenatally, they are associated with chromosomal or congenital abnormalities. Congenital viral infections can also cause effusions. Isolated effusions can be a chylothorax or idiopathic.

c. If asymptomatic and there are no other concerns it is appropriate to simply observe the infant. Idiopathic effusions may resolve while a chylothorax may increase once feeding is commenced. Careful observation and repeat X-rays are essential.

d. If there is respiratory distress the infant may need respiratory support and draining of the effusion.

e. This would depend upon how unwell the baby was and whether fluid had been drained. In an asymptomatic baby baseline haematology and biochemistry may be indicated and little else. If unwell, viral titres may be indicated, as may chromosome analysis. If pleural fluid is drained, the fluid should be sent for cytology, biochemical and microbiological analysis. A high lymphocyte count indicates a chylothorax.

19.

a. There is fluid in the horizontal fissure and some peri-hilar streaking.

b. The most likely diagnosis is transient tachypnoea of the newborn. However due to the difficulty in accurately diagnosing infection it is common to consider this as a possible differential diagnosis.

c. Close observation and respiratory support such as CPAP may be needed for a short while. Affected infants rarely require more than 40% oxygen or respiratory support for more than three days. Antibiotics should be given until infection has been excluded.

d. The prognosis is good. Most infants recover over 24 hours. There is debate regarding whether infants with TTN are more prone to wheezing in childhood. 4

20.

a.

i. There is an endotracheal tube in situ.

ii. There is a nasogastric tube in situ.

iii. Both lungs show inflammatory and cystic change consistent with bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

iv. The lungs appear hyperinflated – note the bulging pleura on the right.

v. There is loss of the left costophrenic angle and obvious outlining of the lungs on the left side with fluid.

vi. There is abnormal separation of the upper ribs on the left.

vii. There is a long line in situ in the left subclavian vein. The position of the tip seems satisfactory.

viii. There is marked oedema visible most obviously outside the chest.

b. The separation of the ribs on the left side of the chest is highly suggestive of a ductal ligation in the recent past. The chylothorax which is present is a well recognised complication of the procedure.

c. This infant has bronchopulmonary dysplasia and is still ventilated. The treatment options available at this stage would be a short course of diuretics or steroids. Diuretics can improve oxygenation and lung compliance, but it is prudent to give a short course to assess for response before embarking on long-term diuretic use due to the high incidence of side effects.

21.

b. The chest appearances are consistent with chronic lung disease and in this case the tracheal deviation is likely to be due to fibrotic changes in the right upper chest. The baby is likely to have been in hospital for some weeks and osteopenia of prematurity has developed. The rib fractures are probably a result of the osteopenia. In this particular case it is of interest to note that alkaline phosphatase and plasma calcium and phosphate had been within the normal ranges throughout the majority of the admission.

22.

a. There is a ‘double bubble’ with a dilated stomach and duodenum.

b. Duodenal atresia.

c. Additional problems may be Down syndrome, cardiac abnormalities and malrotation.

d. A large-bore nasogastric tube must be inserted and left on free drainage; electrolyte and blood gas anomalies must be corrected.

e. Isolated duodenal atresia can be successfully corrected by surgery although experience at such early gestation is very limited. Other anomalies such as cardiac defects (which are much commoner with duodenal atresia) will affect the prognosis.

23.

a.

i. There is a naso-jejunal tube in situ.

ii. There is a very large translucency covering much of the abdomen. This ‘football sign’ indicates free air in the peritoneal cavity.

iii. There is a white line running to the right of and almost parallel to the vertebral column. This is the falciform ligament and it only becomes visible when there is free intraperitoneal gas.

iv. The lung fields are patchy throughout. They are extremely low volume yet appear hyperinflated with marked upward slanting of the ribs. It is difficult to interpret how many of these changes are due to intrinsic lung disease and how much to compression from abdominal distension.

b. There is obvious chronic lung disease and definite gastrointestinal perforation. The latter is quite possibly related to the administration of steroids.

c. Management will depend upon the severity of illness. If his condition has become unstable and gases have deteriorated, ventilation will be required. If the abdominal distension compromises ventilation an abdominal drain may well be required. Surgical review and consideration for a laparotomy will be needed early in the process.

24.

a.

i. The heart shape is ovoid (egg-shaped).

ii. The upper mediastinum is narrow.

iii. The lung fields appear normal.

b. Transposition of the great arteries.

c. The diagnosis should be confirmed by echocardiography. A prostaglandin infusion should be started and the case should be discussed with the nearest paediatric cardiac centre as soon as possible.

25.

b. Respiratory distress with incorrectly placed UAC and ET tube.

c.

i. The UAC will need to be withdrawn into a more appropriate position.

ii. The endotracheal tube will need to be inserted further.

iii. A nasogastric tube should be inserted and the intestines decompressed.

iv. Surfactant administration should be considered.

26.

a.

i. The heart is much larger than normal.

ii. The lung fields appear well aerated.

iii. Pleura bulging on both sides.

iv. UAC on the left – very high (probably – this cannot be confirmed to be the UAC until the abdomen is X-rayed and the caudal loop is seen).

v. UVC on the right, very high (position confirmation needed as above).

b. A diabetic cardiomyopathy is the most likely diagnosis. Although septal hypertrophy is the best described association, biventricular hypertrophy may develop with significant and serious reduction in stroke volume.

c.

i. Reposition the lines.

ii. Echocardiography.

iii. Seek expert advice if haemodynamically unstable.

27.

a.

i. The chest is small.

ii. The ribs are thin and slope downwards steeply.

iii. There is a UVC about 1 cm above the diaphragm.

iv. The UAC tip is at T9.

v. The endotracheal tube tip is very high and is only just visible on the X-ray.

b. Pulmonary hypoplasia secondary to oligohydramnios.

28.

a.

i. There is free gas in the peritoneal cavity.

ii. There are dilated loops of bowel, several of which appear to have very irregularly thickened walls.

iii. The right diaphragm appears thickened.

iv. There is no gas in the rectum.

b. There is intestinal perforation which has probably been present some time to result in the degree of bowel wall thickening that is apparent. The presence of irritant material is also probably responsible for thickening of the diaphragm. It is not clear why the bowel has perforated but the absence of rectal gas may be suggestive of an obstruction. In this baby’s case there was colonic atresia.

c. The free gas will need drain insertion, unless a laparotomy is performed immediately. Surgical review is essential and the baby should be stabilised as dictated by clinical condition.

29.

a.

i. The film is extremely rotated and it is difficult to accurately place anything in the picture.

ii. There is a line to the right of the vertebral column that could be a UAC, but this cannot be stated with any certainty.

iii. There is an endotracheal tube which is slightly high.

b. The line position is almost certainly unsatisfactory.

c. The line should be removed. A further non-rotated film could be obtained but the position of the line is likely to be more lateral if this is done.

30.

a.

i. The lungs show diffuse patchy opacities consistent with chronic lung disease.

ii. The lungs are relatively small volume and hyperinflated, with upward sloping ribs.

iii. There are vertebral abnormalities.

b. No action is indicated although it is assumed that a detailed examination has already been performed to exclude any other anomalies that may be associated with the vertebral abnormalities.

31.

a.

i. The lungs are hyperinflated.

ii. There is a nasogastric feeding tube in place.

iii. There is what is probably a UAC, with the tip at around T8.

iv. There is an endotracheal tube.

v. There is widespread patchy shadowing which appears consistent with cystic changes throughout both lung fields.

b. These apparently cystic changes are compatible with chronic lung disease. Although the diagnosis of CLD (or BPD) is dependent on a prolonged oxygen requirement changes may be present well before then and can be seen histologically in infants who have died only a few days after birth. The distribution and pattern of the changes is different from that expected with pulmonary interstitial emphysema, which also gives widespread cystic changes.

32.

a.

i. There is an endotracheal tube.

ii. There is a nasogastric tube.

iii. There is opacification of the left lung, consistent with RDS.

iv. The right lung has cystic change throughout, consistent with pulmonary interstitial emphysema.

v. There is a large bulla at the base of the right lung.

b. The presence of pulmonary interstitial emphysema in the right lung and what appears to be quite severe RDS in the other lung suggests that the endotracheal tube may have been in the right main bronchus at the time of the first surfactant administration. As one lung is now well expanded and the other solid, any further surfactant is likely to also go into the right lung.

c. Ventilatory management of this baby will be difficult. The left lung needs aeration and thus recruitment of alveoli. The ideal way to do this is to use higher ventilatory pressures to both recruit and retain alveolar expansion. Unfortunately the right lung is showing signs of cystic change and over-distension with a bulla in the right base, and high pressures will result in further damage. High frequency may be useful and anecdotally it has been suggested that paralysing the baby and ventilating with the PIE side down may minimise damage to the PIE side and facilitate inflation of the atelectatic side.

33.

a.

i. There is a nasogastric tube.

ii. There are loops of dilated bowel but no evidence of inflammatory changes, thus making NEC unlikely.

iii. There is no air in the rectum.

b. Either structural or functional bowel obstruction is likely. There is nothing on the X-ray that allows differentiation between possible causes. Maternal diabetes is associated with a small left colon in the newborn baby. This results in a functional obstruction that usually resolves with time (as it did with this infant).

c. A contrast study is probably indicated. Further investigations will depend on the result of this. The baby should not be fed, intravenous fluids should be given and a nasogastric tube should be left on free drainage.

34.

a.

i. There is extremely poor lung inflation.

ii. The diaphragms are very high.

iii. The ribs are thin, particularly on the posterior aspect.

b. Myotonic dystrophy.

c. The baby will need ventilating. There is normally some improvement over time, although it may be a long time before breathing is strong enough to allow extubation.

35.

a.

i. There is an endotracheal tube in place.

ii. There is a line with a tip at approximately T11. It is not clear what this line is.

iii. There is an endotracheal tube at an appropriate position.

iv. There is what appears to be a central venous line with the tip below the sternal end of the left clavicle.

v. Both lungs are very poorly aerated.

vi. There is a fracture of the left arm. The bones do not appear particularly osteopenic and this is presumably traumatic in origin.

36.

a.

i. There is a nasogastric tube with the end in the mid-thoracic oesophagus.

ii. The lungs have diffuse patchy opacification consistent with chronic lung disease.

b. The nasogastric tube needs to be repositioned and as much gas removed from the intestines as possible.

37.

a.

i. There is an endotracheal tube and nasogastric tube.

ii. There is a fine-bore central venous catheter with the tip in the thoracic inlet.

iii. There is a large-bore central venous catheter on the right with the tip at the junction of the SVC and right atrium.

iv. The right lung is opaque with no areas of aeration.

b. Surgical placement of a central venous catheter. The large-bore catheter is a Broviac line.

38.

a.

i. There is free gas above the liver in this lateral X-ray.

b. Gastrointestinal perforation.

c. Surgical referral. A drain may need to be inserted pending laparotomy.

39.

a.

i. There are bilateral pneumothoraces.

ii. There is an endotracheal tube in position.

b. Pneumothoraces may have been present at birth, following the gasping respirations or following initial ventilation. Bilateral pneumothoraces may be difficult to diagnose because all signs are equal on both sides. Although a needle drain may allow re-inflation the lung will expand onto the needle which can easily become blocked.

c. Immediate insertion of bilateral chest drains.

40.

a.

i. There is an endotracheal tube, the tip of which is too high.

ii. There is a nasogastric tube.

iii. There is patchy opacification of both lungs.

iv. There is enlargement of both liver and spleen.

b. The combination of growth retardation, a petechial rash and hepato-splenomegaly is highly suggestive of a congenital infection. Cyto-megalovirus is the most likely candidate. A pneumonitis may develop with CMV infection although it is rarely present at birth and most commonly associated with perinatally acquired infection.

c.

i. Blood needs to be sent for CMV testing.

ii. Further investigations should look for other evidence of CMV damage – an echocardiogram to look for congenital heart defects and cerebral ultrasound, CT or MRI to look for intracranial calcification and evidence of lissencephaly or polymicrogyria that may occur with early infection.

iii. If the diagnosis is confirmed, treatment with anti-CMV chemotherapy should be considered. There is some encouraging information on the use of ganciclovir.

41.

a.

i. There is dilated bowel with thickened walls, mainly on the right side of the abdomen.

ii. There are areas of bowel with intramural gas.

iii. The gut distribution is opposite to that expected. The stomach (see NGT position) is on the right, liver on the left.

b. The central line is passing to the left of the spine.

c. The appearances suggest necrotising enterocolitis in a baby with situs inversus. The appearances are typical of NEC. The distribution of the abdominal contents and the left sided position of the inferior can only be explained by situs inversus. The very small amount of heart visible appears to be on the left but further investigation would be needed to exclude dextrocardia.

42.

a.

i. There is an endotracheal tube with a high tip.

ii. There is a central line which is probably an umbilical arterial line with the tip at T8.

iv. The lungs are hyperinflated with 11 posterior rib ends showing and with flat diaphragms.

v. The heart appears moderately compressed.

b. Mean airway pressure should be reduced or ventilation should be changed to a different modality.

43.

a.

i. There is a central venous catheter entering from the right arm.

ii. There is patchy shadowing of both lungs.

iii. There is a nasogastric tube, the end of which cannot be seen.

iv. There is gaseous distension of the stomach and intestines.

v. The endotracheal tube is not in the trachea – it is almost certainly in the oesophagus.

b. Ventilation of the gastrointestinal tract.

c. Remove the ET tube and either re-intubate or try CPAP. Gas should be sucked out of the gastrointestinal tract if possible and the nasogastric tube should then be put on free drainage.

44.

a.

i. There is an endotracheal tube in the correct position.

ii. There is a central line which is probably an umbilical arterial catheter with the tip at T11–12.

iii. The lungs are very small volume.

iv. There are pleural effusions, more marked on the right than the left.

v. There are two echodensities over the right lung field and one over the left. Each has the appearance of a small cylinder.

b. In-utero drainage of pleural effusions using drains with pigtails on both ends. The echodense bodies are markers – one on each end of the drains.

c. Pleural effusions of this severity are uncommon. In the absence of other signs of hydrops, pulmonary lymphangiectasia is a definite possibility.

45.

a.

i. There is an endotracheal tube that is high.

ii. There is a nasogastric tube in position.

iii. The lungs show patchy shadowing in both fields.

iv. There is a central venous line which appears to have been inserted through a scalp or neck vein. The end is resting within the right atrium.

b. The central venous line needs to be withdrawn to lie outside the heart.

46.

a.

i. There is an endotracheal tube.

ii. There is a nasogastric tube.

iii. There is a central venous line which appears to have been inserted through a vein in the right arm. It has passed in a cephalad direction. The tip is not visible but probably lies in either the neck or the head.

b. The line needs to be withdrawn until the tip lies in the region of the thoracic inlet.

47.

a.

i. There is an endotracheal tube that is very high.

ii. There is a nasogastric tube with the tip in the stomach.

iii. There is an umbilical arterial line with the tip at T5.

iv. There is an umbilical venous catheter which deviates to the right and appears to lie within the liver.

48.

a.

i. There is an endotracheal tube that is slightly high.

ii. There is a central venous line with the tip at the thoracic inlet.

iii. There is an umbilical venous line with a very low tip.

iv. There is a large amount of oedema, very obvious on the sides of the chest.

v. The lungs show dense shadowing and there may be some parenchymal cysts compatible with pulmonary interstitial emphysema.

vi. There is a left tension pneumothorax with mediastinal shift to the right.

b. Although a pneumothorax of this size should be easily detected by trans-illumination the oedema around the chest will have resulted in a diffuse brightness that may well have concealed the pneumothorax.

c. A chest drain must be inserted immediately.

49.

a. There are fixed loops of dilated bowel that do not change from one X-ray to another.

b. This unchanging appearance is highly suggestive of dead bowel. NEC is the most likely underlying cause.

c. Surgical referral is needed. A laparotomy will be required at some point and an abdominal drain may be required as an interim measure.

50.

a.

i. There is an endotracheal tube that is high.

ii. There is a central venous line entering from the right arm that is slightly too long.

iii. There is what is probably an umbilical arterial line, with the tip at T8/9.

iv. The lung fields are poorly aerated.

v. There is a nasogastric tube which is passing down into the right lung.

vi. There is gas in the stomach.

b. There is a tracheo-oesophageal fistula or cleft. Although it is possible to pass a nasogastric tube into the trachea it should not be possible to do so when an endotracheal tube is in place as is the case here. The nasogastric tube is gaining access to the trachea through a fistula or cleft lower down.

c. The nasogastric tube needs to be removed. The endotracheal tube should be inserted further to see if it can block a fistula, otherwise ventilation will be very difficult. A surgical opinion should be sought.

REFERENCES

1. Bell, MJ; Ternberg, JL; Fagin, RD; et al., Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging, Ann Surg 187 (1978) 1–7.

2. Blakely, ML; Tyson, JE; Lally, KP, Laparotomy versus peritoneal drainage for necrotizing enterocolitis or isolated intestinal perforation in extremely low birth weight infants: outcomes through 18 months adjusted age, Pediatrics 117 (2006) e680–e687.

3. Moss, RL; Dimmitt, RA; Barnhart, DC; et al., Laparotomy versus peritoneal drainage for necrotizing enterocolitis and perforation, N Engl J Med 354 (2006) 2225–2234.

4. Shohat, M; Levy, G, Transient tachypnoea of the newborn and asthma, Arch Dis Child 64 (1989) 277–279.