186 Wound Repair

• Thoughtful consideration of the patient, characteristics of the wound, and selection of an appropriate technique for closure is the most important aspect of wound care.

• Antibiotics are not a substitute for adequate wound preparation, irrigation, and exploration.

• Following gross decontamination, the pressure of an irrigating stream must be sufficient to overcome the adhesive force of bacteria (5 to 12 psi).

• Proper skin eversion and suture placement make a difference and take no significantly greater amount of time than does hastily managing a wound.

• Address tetanus status and allergies in all patients.

• Immobilization, a clean moist environment, elevation, and avoidance of sun are the key elements of aftercare.

• Diligent documentation needs to include information regarding the patient’s characteristics, the wound’s appearance, previous care, assessment of the functionality of surrounding structures before and after intervention, and steps taken to reduce infection, as well as the actual closure technique.

Acknowledgment and thanks to Dr. E. Parker Hays, Jr., for his work on the first edition.

Epidemiology

Approximately 12 million wounds are treated in EDs in the United States each year.1 Data on the true incidence of wounds are limited because many are thought to be treated away from the ED or urgent care setting. Of individuals with wounds seen in the ED, the majority are men.2 Wounds can clearly occur anywhere on the body, but lacerations on the upper extremities, head, and neck constitute the majority of cases encountered in EDs.

Pathophysiology

Skin, the largest organ in the body, has numerous functions, most prominently heat exchange, prevention of infection, and provision of a tactile interface with the environment. The layers of skin—epidermis, dermis, and connective tissue—all play different roles in wounds and healing. The thickest and most important layer, the dermis, serves as structural integument, supports conveyance of nutritional and waste products, and contains cutaneous nerves (Fig. 186.1).

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Wound repair may be sought intentionally or be required following evaluation of other complaints, such as a syncopal event. It is not uncommon for patients to be entirely unaware of their wounds (as in trauma) or to be unimpressed with the severity of their lesion because of more painful conditions, such as a fracture. For all these reasons, a thorough physical examination plus evaluation of all wounds is required. Through this evaluation and assessment of the patient’s unique situation, an appropriate approach may be undertaken to address a wound. The overall risk for infection and the likelihood of complications can be predicted by considering wound and host factors. A major pitfall of wound management is fixation on the wound without sufficient attention to the host. For example, a 4-cm linear laceration on the arm of a healthy 18-year-old patient has a different prognosis than the same wound on the shin of a 73-year-old diabetic patient with peripheral vascular disease (Box 186.1).

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Patient Evaluation

A wound is the physical manifestation of an injurious force exerted on the body. Accordingly, careful evaluation of the patient as a whole is critical. A common pitfall is focusing on the most visible injury and not recognizing other lesions that were caused by one event, such as trauma. Understanding the injurious mechanism also enables better prediction of the wound’s severity. As an example, blunt force injuries have significantly greater potential for diffuse tissue nonviability and are consequently more prone to infection.3 Once all injuries have been catalogued, each may be addressed. Important considerations include knowing how the patient was injured (shear, abrasion, compression), whether the location of the wound is in a cosmetically or functionally vital area, and whether potentially confounding influences on the potential for healing are present.

Injury to Underlying Structures

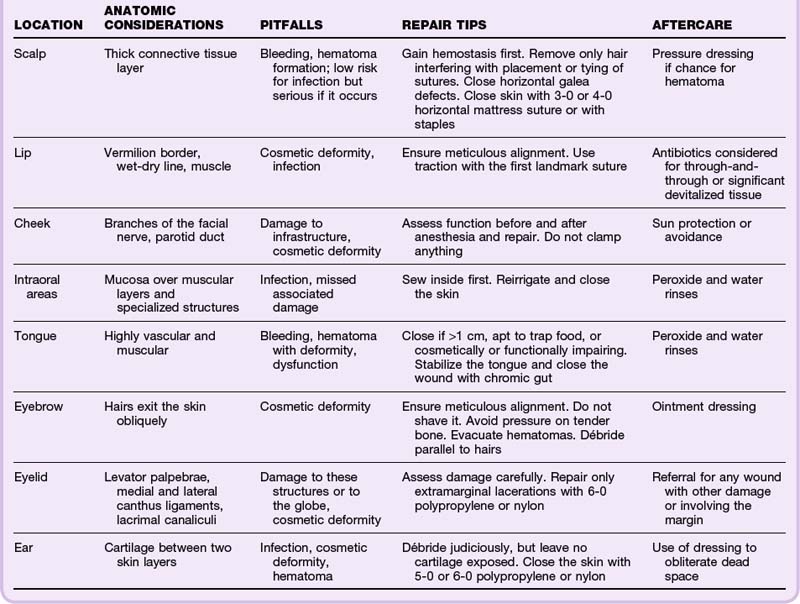

When sufficiently breached, skin fails in its protective role and may allow underlying structures to be injured (Fig. 186.2). Diligent assessment of the functionality of surrounding anatomic structures is of utmost importance.

Foreign Bodies

Foreign bodies can be driven into wounds through innumerable routes of entry. Common situations include shattered glass in motor vehicle accidents, vegetative material in wounds during outdoor pursuits, and puncture wounds through footwear. Foreign bodies increase the risk for infection and may prevent healing. The following section on puncture wounds specifically addresses foreign bodies in these situations. For additional discussion of foreign body evaluation and management, see Chapter 187.

Treatment

The emergency physician (EP) can close most wounds; some situations requiring specialist consultation are listed in Box 186.2.

Box 186.2 Wounds Requiring Specialty Consultation

Wound Preparation

Tips and Tricks

Wound Preparation

Sterile Technique

Use of sterile fields, gloves, caps, masks, and gowns is de rigueur in operating room surgery but not as well established in routine wound closure. Studies have shown that the use of sterile versus nonsterile boxed gloves in routine wound management may not have a significant effect on the rate of infection.4 Powdered gloves should be avoided because of their association with granuloma formation, and EPs must be aware of possible latex allergy.

Anesthesia

In general, anesthesia should precede significant efforts at cleansing, irrigation, exploration, and closure. Despite long-held dogma, lidocaine with epinephrine can be used in most areas of the body, including the majority of hand wounds and digital blocks.5 For a complete discussion of local and regional anesthesia, please see Chapter 188.

Wound Cleansing and Irrigation

The goals of wound cleansing and irrigation are to remove gross contaminants and particulate matter, reduce bacterial counts in the wound, and avoid impeding the host’s responses and natural defenses. In general, ideal wound irrigation requires sufficient pressure and volume while providing drainage and preventing operator exposure. If large particles are present, gross decontamination should be performed before pressure irrigation. A sink, an intravenous infusion set, or holes made in the plastic top of a saline solution bottle can be used to make a spray of water for removing leaves, dirt, and other large contaminants. Following gross decontamination, the pressure of the irrigating stream must be sufficient to overcome the adhesive force of bacteria (5 to 12 psi). Such pressure can be produced with a 35- or 50-mL syringe and a 19-gauge catheter or a commercial device with an integrated splash cup.6 Excessive pressure during irrigation may actually cause additional harm and should be avoided.

The composition of irrigating fluid has been debated and studied inconclusively, but no significant inferiority has been demonstrated for normal saline. Antiseptics such as povidone-iodine kill bacteria in wounds, but they can also kill fibroblasts and harm normal tissue in the process, particularly if the antiseptics are not diluted to less than the typical 10% preparations. Anecdotally, some clinicians reserve diluted povidone-iodine irrigation for grossly contaminated or high-risk wounds and use saline solution for other wounds, but no conclusive evidence supports this approach.7 At the other end of the spectrum, some studies demonstrate favorable results when irrigation with tap water is used rather than sterile water or saline solution.8 The benefits of using water for irrigation include ease of use and drainage and some modest cost savings. Tap water may be used for irrigation of wounds on body parts well suited to it (e.g., the hand), either alone or as an adjunct to subsequent pressure irrigation, depending on the risks associated with the individual wound and host. In summary, the composition of the fluid is much less important than its mechanical action in decontaminating a wound.

Planning the Repair

The first decision to be made is whether to close a wound primarily. The time elapsed since the injury, the degree of contamination, host factors, and wound factors all play a role in deciding the best option. Primary closure refers to mechanical apposition of the wound edges with subsequent wound healing. Delayed primary closure is the same technique carried out 4 to 5 days after the injury.9 At this point the host’s defenses against infection have been mustered locally, and the risk for subsequent infection with primary closure declines significantly. In secondary closure (secondary intention), gaps between the wound edges become filled with granulation tissue by the body and reepithelialization subsequently occurs.

No well-accepted studies have established firm guidelines for the timing of closure on different portions of the body. Nonetheless, many clinicians agree that certain wounds on the face and head, especially in pediatric patients, have such a low risk for infection that they may be closed after protracted times from injury, including up to 1 to 2 days later. However, wounds of the same size on the hand or forearm of adults probably do have a higher risk for infection after passage of a similar amount of time from injury.10

Wound Closure Techniques

Suture Repair

Selection of sutures for a wound should be based on size, absorbability, tissue reactivity, risk for infection, and ease of use. In general, nonabsorbable and monofilament sutures are the easiest to use and have the least tissue reactivity and risk for infection. They are best for percutaneous closure. Traditionally, absorbable suture is used for subcutaneous closure. However, some cutaneous closures can be done with absorbable suture, thus obviating the need for removal.11,12

Tips and Tricks

Suture Placement

Use longitudinal traction to assess how the wound edges correspond and affix the wound (even temporarily) to maintain appropriate alignment.

If you place a suture that seems poor, use the spot to place another knot and remove the original one.

Muscle can typically be repaired by aligning adjacent tissue.

Do not place sutures in high-risk wounds.

The goal of suturing is to have a trapezoidal stitch to disperse tensile force.

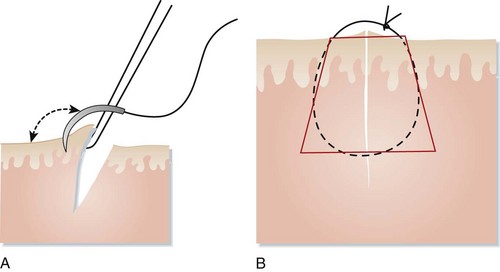

At a minimum, four basic suture patterns should be at the command of EPs: the simple interrupted suture, the corner stitch, and two mattress suture techniques. One should master the simple interrupted pattern first and then move to the others and subsequently to more advanced subcuticular and plastic techniques as required (Fig. 186.3, A and B).

Deep Sutures

Subcutaneous or deep sutures are useful to eradicate a large dead space that could accumulate hematoma and to give structural support to the wound and skin. By drawing the skin edges closer together, these sutures also reduce the tension needed to close the wound percutaneously or may allow closure of the skin with tissue adhesive (Fig. 186.4, A and B).

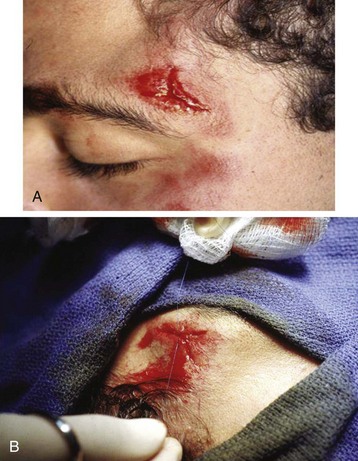

Corner Stitch

A corner suture should be considered when a Y- or V-shaped incision is encountered. The shape of the wound should be assessed for the most advantageous flap to secure into an apex. A corner suture encompasses both percutaneous and subcutaneous portions, but as a single first stitch it can achieve excellent overall wound alignment and thus facilitate placement of subsequent interrupted sutures to finish closing the wound (Fig. 186.5, A and B).

Mattress Sutures

Both horizontal and vertical mattress sutures provide, as a single benefit, better eversion of the wound edges than other sutures do. The horizontal mattress pattern has the additional benefit of some added speed by covering more linear wound length with each knot tie. However, it does result in more pressure on the epidermis by the suture material, which can have cosmetic effects. Horizontal mattress sutures may be useful to evert a problematic section of wound that has a tendency to roll inward. It may then either be replaced with interrupted sutures to hold it in place or be left as is with timely suture removal. Similarly, an isolated vertical mattress suture may be useful to effect better skin eversion (Fig. 186.6).

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Wound Repair

Insufficient preparation will also create issues with wound treatment and resolution.

Tendons may be partially torn or lacerated while range of motion remains intact. Thorough evaluation of any suspected lesion is thus warranted.

Excessively tight sutures—or those without appropriate angles—place an undue amount of pressure on the epidermis that increases the risk for tissue dehiscence and decreases the probability of a good cosmetic outcome.

Negligence in providing appropriate aftercare and home care instructions increases the likelihood that the patient will return to the emergency department and decreases the prospects for good recovery from the injury.

Tissue Adhesives

Tissue adhesives have been approved for use in the United States since 1998. The majority of products today consist of 2-octylcyanoacrylates. These compounds are similar to cyanoacrylate, commonly known as superglue. Additional modifications to the chemical composition have been made in an effort to reduce tissue reactivity, increase pliability of the finished bond, and make the substance more suitable for use on human skin. Studies have demonstrated antibacterial properties of these products as well.13

Tips and Tricks

Placement of Adhesive

Place the patient so that any excess adhesive runs away from important structures such as the eyes.

Have both hands free to place the adhesive; an aide may be useful.

Because each brand of adhesive is different, ensure that the number of coats recommended for the product is applied.

Maintain the wound in the desired position for a sufficient amount of time.

Wound Tape and Strips

Wound tapes or strips may be an option for wounds in which placement of a foreign body (i.e., suture) may be disadvantageous, in initial management of wounds that may undergo delayed primary closure, or in wounds with a protracted time until treatment. Many wounds that were previously closed with wound tapes or strips are now amenable to closure with tissue adhesive. Examples of wounds and their preferred and alternative closure methods are presented in Table 186.1.

Puncture Wounds

By their nature, puncture wounds are different from other lacerations in mechanism, risk, and prognosis. No definitive studies exist to guide evaluation, acute management, or risk stratification of puncture wounds. Despite years of publications, the data available are largely retrospective and observational. What is clear is that plantar puncture wounds, in particular, are commonplace and that many patients do not go to the ED for evaluation. One self-reported survey indicated that 44% of persons had experienced a plantar puncture wound at some time during their life. However, perhaps only half of those wounded underwent medical evaluation.14 It has been assumed that puncture wounds may have a higher complication or infection rate than other wounds, but the true incidence is unknown. Wounds on the plantar surface of the foot that become infected may have very serious complications, including osteomyelitis, osteochondritis, and septic arthritis. The bones of the foot are in close proximity to the skin, and the mechanism of injury typically includes significant force of the weight of the body on the penetrating object.

Many authors believe that the timing of arrival at the ED also guides initial evaluation and treatment. Patients seen within 24 hours of injury tend to have lower rates of cellulitis at the time of evaluation, but they may also have a greater possibility of useful manipulative intervention. Patients seen after 24 hours may have concerns about infection and may be more likely to require invasive exploration for foreign material in the wound.15 One study indicated that 3% of plantar puncture wounds had a foreign body after initial cleansing without exploration.16

Anesthesia of the sole of the foot is mandatory to allow a good degree of wound care and possible exploration or excision. Ankle blocks are relatively easy to perform, they can provide adequate anesthesia for the plantar surface, and they obviate the need for painful injections into the thick connective tissue of the sole (see Chapter 188).

Patients with overt signs of infection should be assumed to have a foreign body in the wound. A thorough radiographic, ultrasonographic, and local search for foreign bodies should be conducted. In the presence of infection or when the clinician decides to use prophylactic antibiotics, a fluoroquinolone may be the best choice because of improved Pseudomonas coverage.17

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Application of an antibiotic ointment is commonly recommended. Whether the petroleum vehicle promotes a moist environment for reepithelialization or the antibiotics have an actual effect is unclear, but at least one study supports the use of these ointments.18 Immobilization should be considered at least until epithelialization occurs (usually 2 days) or considerably longer in wounds subjected to high tension (e.g., laceration over the kneecap or shin). Optimal times for removal of sutures (for a wound that is not under tension) from various body parts are listed in Table 186.2.

| LOCATION | OPTIMAL TIME FOR REMOVAL |

|---|---|

| Hands or fingers | 7-9 days |

| Forearms | 10-12 days |

| Feet | 10-12 days |

| Lower extremity | 10-12 days |

| Torso (chest or back) | 10-12 days |

| Scalp | 5-7 days |

| Face | 3-5 days |

The patient’s scar represents a permanent reminder of the wound, but the medical record is also an enduring account of the events. As a simple guideline with regard to wound documentation, “if you did it or said it, write it” (see the “Documentation” box). Critical elements of record keeping include a description of the mechanism, the patient’s history, and previous home care of the wound; documentation of the function of surrounding structures before and after any medical maneuvers; and description of the steps taken to reduce infection, search for foreign bodies, and close the wound. Furthermore, the instructions given to patients need to include precautions for return, signs of infection, and step-by-step short- and longer-term instructions for aftercare of the wound. Pitfalls in documentation are inadequately addressing the search for a foreign body, irrigation, and assessment of surrounding function, as well as failure to describe the wound’s length and complexity.19

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Wound Repair

History

Detailed mechanism, hand dominance, timing, type of material, whether the object broke on impact or was already broken, whether the wound was soiled, whether anything was pulled out of the wound, FB sensation, paresthesia, weakness, tetanus immunization status, medical conditions that may impair healing or compromise immune function, intravenous drug use, and persistent pain, infection, or drainage

Physical Examination

Position of the hand at rest (if the hand is involved), detailed neurovascular examination distal to the injury including two-point discrimination, ability to perform active range of motion and the presence of pain with passive motion, wound size and depth, tenderness, visible contaminants, infection, tattooing, discoloration, signs of infection, and masses

Patient Teaching

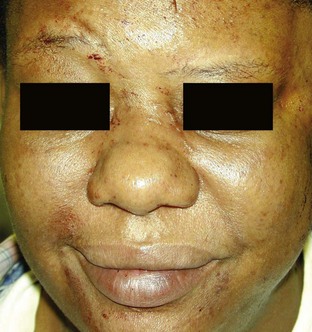

Patients frequently ask, “Will there be a scar?” The inevitable and appropriate answer is yes. However, scars can be minimized by recognition of the aforementioned factors. Patients can serve as their own case controls; earlier scars give clues to how an acute wound may heal. Beyond the initial wound aftercare outlined previously, patients who have a tendency to form hypertrophic or keloid scars should be identified by the EP and informed of treatment options available to decrease the size of the scar. Although many methods have been studied, the only treatments with sufficient prospective data to support their use are silicone gel sheets and intralesional corticosteroid injections.20,21 Additionally, pressure or paper taping and massage over developing scars are simple measures that may be initiated soon after initial wound healing. Sunscreen use is important during the first 6 months to 1 year. Certain topical preparations have been promoted to improve scars aesthetically. Vitamin E cream is popular and available over the counter, but no well-conducted study exists to show its effectiveness for acute lacerations, and at least one study has shown a detrimental effect.22 An onion extract (Mederma) is promoted as a way to make scars “appear” softer and smoother. One prospective study is cited in the company’s literature, but no large studies have yet been published to support its use.23

Capellan O, Hollander J. Management of lacerations in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003;21:205–231.

Dire DJ, Coppola M, Dwyer DA, et al. Prospective evaluation of topical antibiotics for preventing infections in uncomplicated soft-tissue wounds repaired in the ED. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:4–10.

Holger JS, Wandersee SC, Hale DB. Cosmetic outcomes of facial lacerations repaired with tissue adhesive, absorbable, and nonabsorbable sutures. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22:254–257.

Mustoe TA, Cooter RD, Gold MH, et al. International Advisory Panel on Scar Management, 2002: international clinical recommendations on scar management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:560–571.

Singer AJ, Hollander JE, Quinn JV. Evaluation and management of traumatic lacerations. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1142–1148.

1 Singer AJ, Hollander JE, Quinn JV. Evaluation and management of traumatic lacerations. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1142–1148.

2 Capellan O, Hollander J. Management of lacerations in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003;21:205–231.

3 Cardanay C, Rodehaver G, Thacker J, et al. The crush injury: a high risk wound. JACEP. 1976;5:965–970.

4 Martra AK, Adams JC. Use of surgical gloves in the management of sutured hand wounds in the A&E department. Injury. 1986;17:193–195.

5 Denkler K. A comprehensive review of epinephrine in the finger: to do or not to do. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:114–124.

6 Singer AJ, Hollander JE, Subramanian S, et al. Pressure dynamics of various irrigation techniques commonly used in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;24:36–40.

7 Dire DJ, Welsh AP. A comparison of wound irrigation solutions used in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:704–708.

8 Fernandez R, Griffiths R, Ussia C. Water for wound cleansing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2002. CD003861

9 Dimick AR. Delayed wound closure: indications and techniques. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:1303–1304.

10 Morgan MJ, Hutchison D, Johnson HM. The delayed treatment of wounds of the hand and forearm under antibiotic cover. Br J Surg. 1980;67:140–141.

11 Holger JS, Wandersee SC, Hale DB. Cosmetic outcomes of facial lacerations repaired with tissue adhesive, absorbable, and nonabsorbable sutures. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22:254–257.

12 Karounis HG. Plain gut vs. non-absorbable nylon sutures in traumatic pediatric lacerations: long-term. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:448.

13 Quinn JV, Maw JL, Ramotar K, et al. Octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive wound repair versus suture repair in a contaminated wound model. Surgery. 1997;122:69–72.

14 Weber EJ. Plantar puncture wounds: a survey to determine the incidence of infections. J Accid Emerg Med. 1996;13:274–277.

15 Chisholm CD, Schlesser JF. Plantar puncture wounds: controversies and treatment recommendations. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:1352–1357.

16 Schwab RA, Powers RD. Conservative therapy of plantar puncture wounds. J Emerg Med. 1995;13:291–295.

17 Raz R, Miron D. Oral ciprofloxacin for treatment of infection following nail puncture wounds of the foot. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:194–195.

18 Dire DJ, Coppola M, Dwyer DA, et al. Prospective evaluation of topical antibiotics for preventing infections in uncomplicated soft-tissue wounds repaired in the ED. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:4–10.

19 Sullivan DJ. Wound care: retained foreign bodies and missed tendon injuries. ED Legal Lett. 1998;9:45–49.

20 Ahn ST, Monafo WW, Mustoe TA. Topical silicone gel: a new treatment for hypertrophic scars. Surgery. 1989;106:781–786.

21 Mustoe TA, Cooter RD, Gold MH, et al. International Advisory Panel on Scar Management, 2002: international clinical recommendations on scar management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:560–571.

22 Baumann LS, Spencer J. The effects of topical vitamin E on the cosmetic appearance of scars. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:311–315.

23 Chung VQ, Kelley L, Marra D, et al. Onion extract gel versus petrolatum emollient on new surgical scars: prospective double-blinded study. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:193–197.