60 Pericarditis, Pericardial Tamponade, and Myocarditis

• The classic symptom of acute pericarditis is sharp, pleuritic retrosternal chest pain that radiates to one or both trapezius ridges and changes with body position.

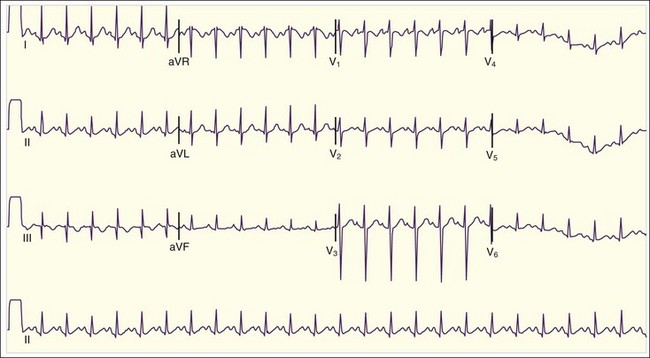

• The hallmark electrocardiographic findings in patients with pericarditis include diffuse ST-segment elevation with PR-segment depression in the same leads.

• High-dose aspirin or a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug with the addition of colchicine is effective treatment of most cases of acute pericarditis.

• Steroids should be avoided in the early treatment of first-time pericarditis because their use may actually increase the chance of recurrence.

• Large pericardial effusions often cause severe tachypnea and dyspnea; however, oxygen saturation levels are usually normal.

• Jugular venous distention is typical in patients with pericardial tamponade, but it may be absent in those with hypovolemia or if the tamponade developed rapidly.

• The hallmark echocardiographic finding in patients with pericardial tamponade is the presence of a large effusion with diastolic collapse of the right heart chambers.

• The classic manifestation of acute myocarditis includes low-grade fever, tachypnea, and tachycardia out of proportion to the fever.

Epidemiology

Acute pericarditis is often subclinical, so its incidence is uncertain. However, rough estimates range from 2% to 6%,1 and this disorder may be responsible for as many as 1 in every 1000 hospital admissions.2 Although acute pericarditis is not usually deadly, it can be painfully disabling if not treated appropriately.

Pericarditis

Pathophysiology

Pericarditis refers to inflammation of the layers of the pericardium. It has many possible causes (Box 60.1), but in most cases the cause is unknown. In the majority of these idiopathic cases the presumed cause is viral, although most attempts to prove a viral cause have low yield. The most common viral cause is coxsackievirus B. The most common cause of pericarditis worldwide is tuberculosis.3

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Classic

Chest pain is the typical complaint of patients with acute pericarditis. Classically, the chest pain is sharp, retrosternal, and pleuritic, and it radiates to one or both trapezius ridges because the phrenic nerve, which traverses the pericardium, innervates these muscles.4 Typically, the pain also changes with body position: it improves when the patient sits up and leans forward and worsens when the patient lies supine.

The physical examination of patients with acute pericarditis is usually nondiagnostic. Although some researchers report the presence of a friction rub in up to 85% of patients at some point in the course of the disease,5 the presence of a friction rub at the time of initial evaluation is unreliable. When a friction rub is present, it is best heard at the left sternal border at end-expiration with the patient leaning forward. The rub is usually described as consisting of three components that correspond to atrial systole, ventricular systole, and rapid diastolic filling. A friction rub is thought to be caused by rubbing of the inflamed layers of the pericardium against each other.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

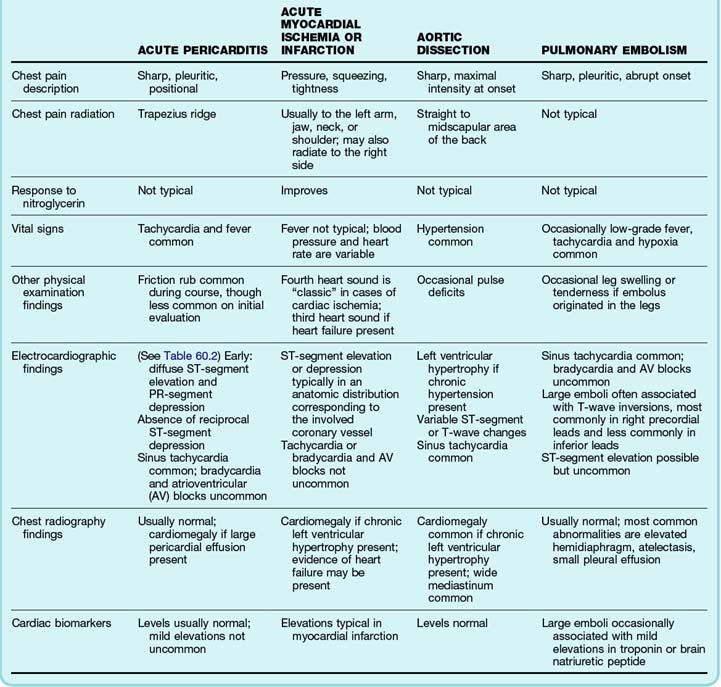

A thorough differential diagnosis of a patient with chest pain is described in Chapter 54. However, the most important initial consideration should always be the deadly causes of chest pain: pericarditis, acute coronary ischemia or infarction, thoracic aortic dissection, and pulmonary embolism. Table 60.1 lists some historical and physical examination features that are helpful in distinguishing among these conditions. Distinction among these causes of chest pain is critical in terms of treatment; patients with pulmonary embolism or myocardial infarction often require treatment with anticoagulants and thrombolytics, medications that can be deadly in patients with acute pericarditis or aortic dissection.

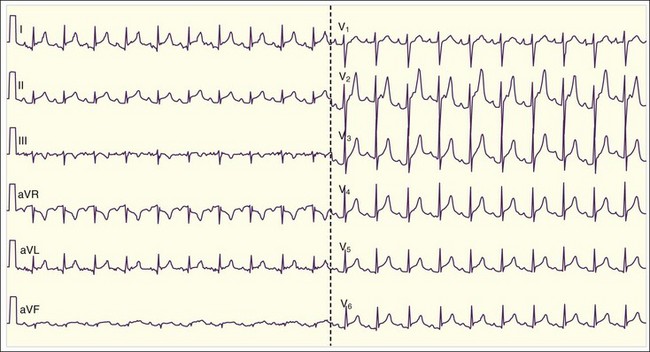

The diagnosis of acute pericarditis is based primarily on the clinical findings. In many cases an electrocardiogram (ECG) is helpful in confirming the diagnosis. Sound knowledge of the ECG findings in patients with acute pericarditis is critical, as well as some findings that help in diagnosing pericarditis versus myocardial infarction (see Table 60.1). Classically, pericarditis evolves through four ECG stages as described in Table 60.2. The first stage of acute pericarditis, characterized by diffuse ST-segment elevation and PR-segment depression or downsloping (Fig. 60.1), is the most common stage encountered in the emergency department (ED). The ST segments should be concave upward; a convex upward (“tombstone”) morphology virtually excludes the diagnosis of pericarditis and rules in acute myocardial infarction. ST-segment depression may be present in leads aVR and V1 in a patient with pericarditis but is unlikely to be present in any of the other 10 leads. In fact, the presence of ST-segment depression in any of the other 10 leads should be considered the “reciprocal” changes of acute myocardial infarction.

Table 60.2 Electrocardiographic Stages of Acute Pericarditis

| Stage I | Diffuse ST-segment elevation and PR-segment depression (except in leads V1 and aVR) |

| Stage II | Resolution of the ST-segment and PR-segment changes T-wave flattening in the same leads |

| Stage III | T-wave inversions in the same leads |

| Stage IV | Normalization of electrographic abnormalities |

Treatment

Treatment of patients with acute pericarditis should be targeted at the underlying cause. The majority of patients with viral, rheumatologic, posttraumatic, or idiopathic pericarditis are effectively treated with high-dose aspirin (2 to 4 g daily) or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Ibuprofen is effective in most cases and has fewer side effects than other NSAIDs; the pain usually improves significantly within days with ibuprofen therapy. If the patient’s symptoms persist, an alternative NSAID is indicated. Indomethacin is often used for severe cases because of its stronger antiinflammatory effect, although it should be avoided in patients with a history of ischemic heart disease because it may decrease coronary blood flow.4,7 Evidence now suggests that addition of colchicine (1.0 to 2.0 mg for the first day and then 0.5 to 1.0 mg/day for 3 months) to the standard regimen is effective in hastening the resolution of acute symptoms and also preventing recurrence rates, regardless of the cause of the pericarditis.8 Colchicine is also effective in cases of recurrent pericarditis.9,10 The use of corticosteroids is generally reserved for recurrent cases of pericarditis that are unresponsive to aspirin or NSAIDs plus colchicine. Initiation of steroids early in the course of first-time pericarditis may actually be an independent risk factor for recurrence.8

Follow-Up and Next Steps in Care

The majority of patients with acute pericarditis can be treated as outpatients, with the symptoms generally resolving within 2 weeks. Outpatient management is suitable for patients with mild symptoms, hemodynamic stability, and ability to tolerate oral medications. Reasonable indications for admission include fever or suspicion of a bacterial cause of the pericarditis, immunosuppression, pericarditis associated with trauma, presence of a moderate to large pericardial effusion, and hemodynamic instability. A history of active anticoagulant use is generally considered a poor prognostic factor and warrants hospital admission as well.4

Pericardial Tamponade

Pathophysiology

Trauma or inflammation of the pericardium can cause fluid to accumulate within the intrapericardial space. Normally, the pericardium is capable of stretching and accommodating 2 L of fluid or more when the fluid accumulates very slowly.11 However, if the fluid accumulates more rapidly than can be accommodated by the distensibility of the pericardium, especially in the case of trauma, in the presence of fibrotic pericardium, or if the volume of pericardial fluid is excessive, significant intrapericardial pressure results and can produce pericardial tamponade.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Classic

The typical symptoms associated with a large pericardial effusion are nonspecific. Malaise, generalized weakness, ascites, and edema are common in patients with subacute or chronic effusions as a result of poor cardiac function.12 Many other symptoms are related to compression of adjacent mediastinal structures by the effusion. Dyspnea and cough are common and may be due to displacement or compression of bronchial structures or lung tissue by the effusion. Dyspnea on exertion is common as well and results from impairment of venous return and cardiac output. Patients often report a sense of dysphagia, which is due to esophageal compression. Hiccups may occur as a result of esophageal compression and involvement of the phrenic and vagus nerves. Hoarseness may result from compression of the recurrent laryngeal nerve.12

Physical findings are also often nonspecific. Tachycardia and tachypnea are common. Despite the presence of tachypnea and dyspnea, however, oxygen saturation levels are usually normal because the effusion itself does not impair alveolar air exchange. Lung sounds are generally normal as well. Findings of hypoxia or focal abnormalities on lung examination should suggest a superimposed pulmonary condition or an alternative diagnosis. Fever is common if the underlying cause is infectious. Pericardial friction rubs are reportedly common if the underlying cause is inflammatory,13 although diminished heart sounds are also frequent because of reduced cardiac function and attenuation of their transmission by the effusion.

When a pericardial effusion produces pericardial tamponade, additional findings are notable. Decreased cardiac function produces hypotension and shock. Jugular venous distention is typically present because of impaired venous return. Pulsus paradoxus (drop in systolic blood pressure of greater than 10 mm Hg during normal inspiration) is also typical, although its presence has limited specificity for pericardial tamponade. Several other conditions that are associated with hypotension or dyspnea (or both) can also produce pulsus paradoxus, including massive pulmonary embolism, hemorrhagic shock, and obstructive lung disease.12 Death is usually preceded by pulseless electrical activity.14

Typical Variations

Although the symptoms and physical findings already noted are common, certain conditions may produce unexpected findings in the presence of pericardial tamponade. Patients who have severe hypothyroidism or uremia or who take atrioventricular nodal blocking agents (e.g., calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, digoxin) may have a relative bradycardia. Jugular venous distention is typical in pericardial tamponade as well, but it is often absent in patients who are hypovolemic or in whom the pericardial tamponade developed very quickly (e.g., after cardiac trauma). Overt hypotension may be absent as well in patients with a history of severe antecedent hypertension.12,15

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

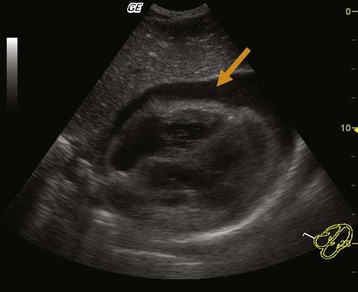

The primary means of diagnosing pericardial tamponade is via two-dimensional echocardiography. A pericardial effusion is easily seen in most patients on subcostal or parasternal views (Fig. 60.2). An echo-free space should be visible throughout the cardiac cycle when the pericardial effusion is at least 25 mL.3 The presence of a pericardial effusion in combination with hypotension and echocardiographic evidence of early diastolic right ventricular collapse and late diastolic right atrial collapse is diagnostic of pericardial tamponade. In approximately 25% of cases, the left atrium also demonstrates collapse, a very specific sign of tamponade. The left ventricle rarely demonstrates collapse except in specific conditions such as localized postoperative tamponade.12 Other echocardiographic findings that may be found in patients with pericardial tamponade are a dilated inferior vena cava without inspiratory collapse and beat-to-beat swinging of the heart within the pericardial fluid (when the effusion is large).3

Fig. 60.2 Large pericardial effusion.

(Courtesy Dr. Brian Euerle, Director of Emergency Ultrasound, Emergency Medicine Residency, University of Maryland School of Medicine.)

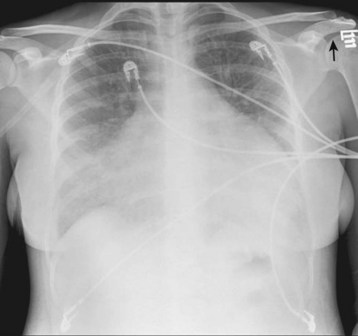

Other imaging studies can be helpful in evaluating these patients as well. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging are very accurate in detecting pericardial effusions, in addition to diagnosing alternative conditions. However, they should not be used in patients with borderline or overt hemodynamic instability because of the need to remove such patients from the ED for the procedures. Chest radiography is primarily used to evaluate the patient for alternative diagnoses as well, such as pneumonia or pulmonary edema. In patients with a large pericardial effusion, cardiomegaly is a nearly universal finding (Fig. 60.3). The chest radiograph is particularly helpful in this setting if previous radiographs are available that demonstrate a normal-sized heart. Previous radiographs that show the massive cardiomegaly to be new are highly suggestive of a large pericardial effusion.

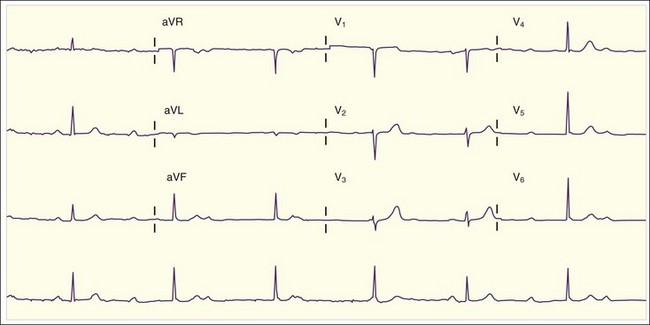

The ECG can be helpful in the diagnosis of large pericardial effusions. The most common abnormality is tachycardia, especially in the presence of tamponade. Low voltage is common as well and is caused by attenuation of the electrical impulse as it passes through the effusion before reaching the ECG electrodes. Although low voltage is nonspecific, the presence of new low voltage (in comparison with previous ECGs) is much more specific for large pericardial effusions. The third “classic” ECG abnormality is electrical alternans. Electrical alternans refers to beat-to-beat variation in amplitudes of the ECG complexes (Fig. 60.4) and is attributed to “swinging” of the heart back and forth within the pericardial fluid. Electrical alternans is present in less than one third of cases of pericardial tamponade. Although none of these three findings individually is completely diagnostic of large pericardial effusions, the combination of all three is very highly specific.

Treatment

Initial management of patients with pericardial tamponade should focus on the typical ABCs of resuscitation (airway, breathing, circulation). Certain caveats should be made, however. Although the primary pathophysiologic abnormality underlying hemodynamic compromise in patients with pericardial tamponade is ventricular filling, the benefit of volume infusion to improve filling is controversial. Animal studies have shown variable results with respect to the hemodynamic benefit of volume infusion,12,16 which may improve systemic perfusion only in patients with hypovolemia. Strong supporting data in humans are lacking, however. In patients with traumatic pericardial tamponade, large-volume infusions may actually precipitate further deterioration.17 Strong evidence supporting specific inotropic agents is lacking as well, although theoretically agents that reduce the elevated vascular resistance,12 such as dobutamine and milrinone, would seem ideal. Mechanical ventilation should generally be avoided except in patients with respiratory failure; the positive airway pressure associated with mechanical ventilation decreases venous return and cardiac output.

Treatment of pericardial tamponade is drainage of the intrapericardial fluid (pericardiocentesis). Drainage is best performed via needle aspiration under echocardiographic, CT, or fluoroscopic guidance. In patients who exhibit rapid cardiac decompensation or are in cardiac arrest, the EP should perform emergency pericardiocentesis without waiting for imaging guidance. The procedure is performed with a 16- or 18-gauge needle, most commonly inserted into the left paraxiphoid area of the chest. The needle is pointed downward at an approximately 30-degree angle to the chest to bypass the left costal margin and is aimed toward the left shoulder. The needle should be inserted and advanced slowly until the pericardium is penetrated and fluid is aspirated. Use of a sheathed needle can facilitate the process—once the pericardium has been penetrated, the core of the needle can be removed with the sheath left in the pericardial space to assist in further removal of fluid.12 Some researchers have advocated attaching ECG leads to the hub of the needle so that when the pericardium is penetrated, an injury pattern (i.e., ST-segment elevation) will be noted.18 However, a recent review recommends against this practice because of the likelihood of misleading results.12

In patients with acute cardiac decompensation, aspiration of even 10 to 20 mL of blood should be sufficient to produce some hemodynamic improvement. However, once full cardiac arrest has occurred, pericardiocentesis has a limited success rate. Potential complications of pericardiocentesis include puncture or laceration of the cardiac chambers, injury to coronary vessels, pneumothorax, ventricular dysrhythmias, pneumopericardium, and delayed infection.19 These complications are more common in the setting of emergency pericardiocentesis, which is sometimes performed without imaging guidance.

Myocarditis

Pathophysiology

Myocarditis is an inflammatory condition that causes myocardial damage, usually because of infectious, immunologic, or toxin-mediated conditions (Box 60.2). Myocarditis can be manifested as mild constitutional symptoms, moderate cardiopulmonary symptoms, or fulminant cardiopulmonary decompensation leading to death. In the majority of adult cases, the myocardial damage is believed to be caused by autoimmune processes that are often triggered by viral or other infections,20 whereas in neonates and infants, injury to myocytes is believed to occur more often because of direct injury by the pathogen itself.21

Approximately 10% of postmortem examinations demonstrate some degree of histologic evidence of myocarditis. However, most of the patients were not clinically symptomatic before death.22 Conversely, in patients in whom myocarditis is diagnosed clinically, only one third have histologic findings consistent with the disease. Even in cases that progress to dilated cardiomyopathy, only 40% of patients have microscopic evidence of myocarditis. Consequently, the actual incidence of myocarditis is unknown.23

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Classic

The clinical manifestations of myocarditis usually begin days to weeks after the acute infection, especially when viruses are implicated as the cause. However, only 50% of patients report a recent upper respiratory or gastrointestinal viral type of infection.23 The initial symptoms are nonspecific and constitutional in nature: low fever, fatigue, malaise, myalgia, and arthralgia. These mild symptoms are often the reason for initial misdiagnosis or delays in proper diagnosis of this condition. Cardiopulmonary symptoms, especially mild dyspnea and chest pain, are common as well. The chest pain can be pleuritic, sharp, and positional, much like pericarditis, or substernal and squeezing, much like typical ischemic pain. Patients with congestive heart failure may report more significant dyspnea, as well as cough, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and edema. Less commonly, patients may initially be seen after a syncopal episode, usually the result of a bradydysrhythmia.

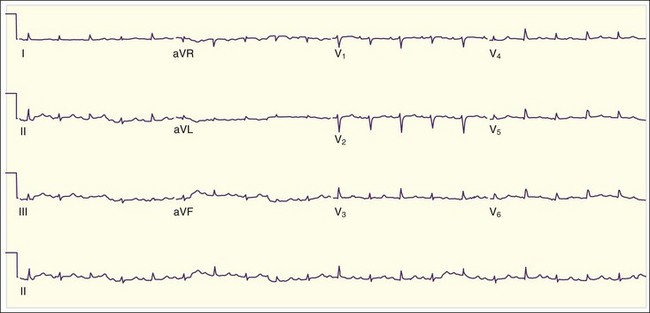

The physical findings are often notable for low-grade fever, tachypnea, and tachycardia. Classically, the patient has “tachycardia out of proportion to the fever”—extreme tachycardia without obvious hypovolemia or high fever (Fig. 60.5). Patients may also experience bradycardia if a high-grade atrioventricular block develops (Fig. 60.6). Evidence of congestive heart failure is frequently present as well: jugular venous distention, bibasilar rales on lung examination, a third heart sound (S3) on cardiac examination, and peripheral edema. Patients with advanced or fulminant myocarditis may arrive at the ED in full cardiogenic shock.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The initial diagnostic evaluation should be prompted by clinical suspicion. The finding of cardiopulmonary complaints, unexplained tachycardia, or evidence of congestive heart failure on examination in young patients should prompt consideration of myocarditis. An ECG and chest radiograph are appropriate initial tests in these patients. Despite the absence of a specific or single diagnostic ECG abnormality, the majority of patients with myocarditis have at least some abnormality noted on the ECG. The most common abnormalities are sinus tachycardia (see Fig. 60.5) and nonspecific ST-segment or T-wave changes. Other abnormalities that may occur in patients with myocarditis are conduction abnormalities (new fascicular blocks, new bundle branch blocks, and atrioventricular blocks), atrial or ventricular tachydysrhythmias and bradydysrhythmias, overt ischemic changes (T-wave inversions, ST-segment changes), and Q-wave formation. The ischemic changes are often indistinguishable from those seen with true cardiac ischemia or myocardial infarction. If the pericardium is also involved (myopericarditis), PR-segment depression with concurrent ST-segment elevation may be found. If a pericardial effusion develops, low voltage may occur. The ECG findings are rarely completely normal.

Echocardiography may also be helpful in the ED, especially when there is confusion in distinguishing between myocarditis and acute coronary syndrome. Echocardiography in patients with acute coronary syndrome (with active ischemia) usually demonstrates focal wall hypokinesis. Patients with myocarditis can also have focal hypokinesis, but they are more likely to have diffuse hypokinesis and multichamber dilation as well.23 In addition, the echocardiogram can demonstrate evidence of complications, such as pericardial effusion or intracardiac thrombus.

Endomyocardial biopsy is usually considered the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of myocarditis. Evidence of microscopic myocardial inflammation with various levels of necrosis is generally used to diagnose and categorize stages of myocarditis.23,24 However, biopsy is not feasible in the ED. Additionally, recent reports have questioned the sensitivity and specificity of the test.23,25

Treatment

Close attention should be paid to the ABCs of resuscitation because patients with fulminant myocarditis can decompensate rapidly. The mainstay of treatment of myocarditis is primarily supportive with a focus on hemodynamic support and management of complications. Congestive heart failure and hypoxia should be treated as usual, with high-flow oxygen, preload and afterload reduction, and diuretics. The patient’s fluid status must also be monitored closely because of the risk for congestive heart failure. Bradydysrhythmias should be managed as usual. Patients with high-degree atrioventricular blocks often require pacemaker placement. Tachydysrhythmias should generally be managed as usual, although preference should be given to titratable medications because drugs with negative inotropic effects can precipitate unpredictable hemodynamic collapse in these patients with myocarditis, whose status is tenuous. Intramural thrombi noted on echocardiography should be treated with anticoagulation. The benefit of prophylactic anticoagulation is uncertain, especially given the risk that these patients have for hemopericardium. Additional myocardial workload reduction can be accomplished through fever reduction and correction of anemia.23

Patients in shock should be treated aggressively. Adequate perfusion should be achieved in hypotensive patients through the use of vasopressors (e.g., dopamine, norepinephrine) and positive inotropic agents (e.g., dobutamine). Ventricular assist devices, intraaortic balloon counterpulsation, and cardiopulmonary bypass have been used successfully in some patients during the wait for clinical improvement or cardiac transplantation.23

Antiviral therapy may be helpful during the patient’s hospital course if a viral cause of the myocarditis has been determined. Other therapies should be focused on the determined underlying condition (e.g., Lyme carditis, toxin-induced myocarditis). Immunosuppressive medications have been used successfully in some patients in the later stages of illness, but this experience appears to be anecdotal only.26 The use of corticosteroids lacks good evidence of benefit as well. High-dose intravenous gamma globulin has been used successfully in some pediatric patients, with improvement in ventricular function at 1 year.23

1 Mast HL, Haller JO, Schiller MS, et al. Pericardial effusion and its relationship to cardiac disease in children with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:548.

2 Lorell BH. Pericarditis. In: Braunwald E, ed. Heart disease. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1997:1478.

3 Aikat S, Ghaffari S. A review of pericardial diseases: clinical, ECG and hemodynamic features and management. Cleve Clin J Med. 2000;67:903.

4 Lange RA, Hillis LD. Acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2195.

5 Zayas R, Anguita M, Torres F, et al. Incidence of specific etiology and role of methods for specific etiologic diagnosis of primary acute pericarditis. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:378.

6 Spodick DH. Pericardial rub: prospective, multiple observer investigation of pericardial friction in 100 patients. Am J Cardiol. 1975;35:357.

7 Schifferdecker B, Spodick DH. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of pericarditis. Cardiol Rev. 2003;11:211.

8 Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, et al. Colchicine in addition to conventional therapy for acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2005;112:2012.

9 Adler Y, Finkelstein Y, Guindo J, et al. Colchicine treatment for recurrent pericarditis: a decade of experience. Circulation. 1998;97:2183.

10 Millaire A, de Groote P, Decoulx E, et al. Treatment of recurrent pericarditis with colchicine. Eur Heart J. 1994;15:120.

11 Reddy PS, Curtiss EI, O’Toole JD, et al. Cardiac tamponade: hemodynamic observations in man. Circulation. 1978;58:265.

12 Spodick DH. Acute cardiac tamponade. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:684.

13 Spodick DH. Pericardial rub: prospective, multiple observer investigation of pericardial friction in 100 patients. Am J Cardiol. 1975;35:357.

14 Cooper JP, Oliver RM, Currie P, et al. How do the clinical findings in patients with pericardial effusions influence the success of aspiration? Br Heart J. 1995;73:351.

15 Ramsaran EK, Benotti JR, Spodick DH. Exacerbated tamponade: deterioration of cardiac function by lowering excessive arterial pressure in hypertensive cardiac tamponade. Cardiology. 1995;86:77.

16 Cogswell TL, Bernath GA, Keelan MH, Jr., et al. The shift in the relationship between intrapericardial fluid pressure and volume induced by acute left ventricular pressure overload during cardiac tamponade. Circulation. 1986;74:173.

17 Hashim R, Frankel H, Tandon M, et al. Fluid resuscitation–induced cardiac tamponade. Trauma. 2002;53:1183.

18 Harper RJ. Pericardiocentesis. In: Roberts JR, Hedges JR. Clinical procedures in emergency medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:316.

19 Tsang TS, Oh JK, Seward JB. Diagnosis and management of cardiac tamponade in the era of echocardiography. Clin Cardiol. 1999;22:446.

20 Klingel K, Hohenadl C, Canu A, et al. Ongoing enterovirus-induced myocarditis is associated with persistent heart muscle infection: quantitative analysis of virus replication, tissue damage, and inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:314.

21 Ledford DK. Immunologic aspects of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 1992;268:2923.

22 See DM, Tilles JG. Viral myocarditis. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:951.

23 Brady WJ, Ferguson JD, Ullman EA, et al. Myocarditis: emergency department recognition and management. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2004;22:865.

24 Lieberman EB, Herskowitz A, Rose NR, et al. A clinicopathologic description of myocarditis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;68:191.

25 Baughman KL. Diagnosis of myocarditis: death of Dallas criteria. Circulation. 2006;113:593.

26 Mason JW, O’Connell JB, Herskowitz A, et al. A clinical trial of immunosuppressive therapy for myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:269.