195 The Violent Patient

• Patient risk factors for violent behavior include evidence of agitation (e.g., pacing), substance abuse, a previous history of violence, arrival at the emergency department in police custody, and male gender.

• Disarming protocols and deescalation techniques are critical methods for prevention of violence.

• Agitated or violent behavior is frequently caused by medical conditions, such as hypoglycemia or intoxication.

• Violent patients should be given a verbal warning before they are restrained. Physical restraint should be supplanted by chemical restraint when safety allows.

• Medical complications of incorrect or prolonged physical restraint include hyperthermia, acidosis, rhabdomyolysis, and death.

• Sedation should be tailored to the suspected cause of the agitation, as well as the desired depth and length of sedation.

• A combination of an intramuscular benzodiazepine (lorazepam) and a butyrophenone (haloperidol) provides consistent sedation for many causes.

Epidemiology

The goal of caring for a violent patient is first to protect everyone involved and also to diagnose and treat important medical and psychiatric conditions (see the “Priority Actions” box). These goals are best achieved if warning signs of violence are recognized and the safest and most effective means of behavioral control are used.

The epidemiology of violence in the emergency department (ED) is inexact; past surveys suggest that as many as 80% of events are unreported.1 Still, clear evidence indicates that most EDs experience violent patients routinely. Of greater concern, ED caregivers are often victims. More than 70% of ED nurses have reported being the victim of physical violence during their career.2 The rate of assault on health care workers is 8 per 10,000, as compared with 2 per 10,000 for all private-sector industries, with the ED being one of the highest-risk areas.3

Nearly 60% of EDs in the United States have reported an armed threat on a staff member within 5 years.4 Weapons may be carried by patients, family members, visitors, or even staff members. Patients most likely to carry weapons include those with schizophrenia or paranoid ideation and individuals who have been the victims of gunshot wounds. Many violent patients are intoxicated with alcohol or drugs.

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Goals for the Care of Violent Patients in the Emergency Department

Recognize risk factors and warning signs before violence occurs.

Use deescalation (communication) techniques to prevent violent behavior.

Control the patient and situation to minimize further violence.

Diagnose and treat reversible causes of agitation.

Protect the patient and others through appropriate restraint methods.

How to Predict Violence

Violent behavior rarely erupts without warning. Risk factors for violence include an escalating psychiatric illness (e.g., schizophrenia, personality disorders, mania), alcohol and drug abuse, a previous history of violence, arrival at the ED in police custody, and male gender (Box 195.1). The use of risk factors to predict violent behavior has not been tested in cohorts of emergency physicians; psychiatrists have been only 60% accurate in predicting violence when using risk factors alone.5

Deescalation Techniques

Tips and Tricks

Deescalation Techniques Useful for Prevention of Violence in the Emergency Department

Do

Disrobe and gown all patients regardless of the chief complaint.

Disarm all patients at triage through the use of metal detectors.

Remove dangerous objects from the examination room.

Remove personal objects that can be used as weapons (tie, stethoscope).

Provide preferential, timely, and attentive care.

Make the patient comfortable (offer food, blankets).

Ask permission to enter the room and to examine or touch the patient.

Health care providers can escalate a patient’s behavior through their own instinctive, impulsive, natural human conduct.6 Anger or frustration should never inspire unprofessional behavior or decisions. Physical and emotional distance may minimize the emotional reactions. A buffer zone of at least four body widths between the provider and the patient is recommended.

Treatment

Physical Restraint

Rationale

The use of restraint is indicated when verbal attempts have failed and action must be taken to prevent injury to the patient or staff. Restraint should be used only to facilitate diagnosis and treatment. It is inappropriate to use restraint as punishment or simply to quiet a disruptive patient.7

The Joint Commission has published clear guidelines regarding monitoring, documentation, and the application of physical restraint (Box 195.2). Protection of the patients’ rights, dignity, and well-being is of utmost importance. The decision to apply physical restraint should be assessment driven; the provider must evaluate the individual patient in some way before a restraint is applied. It is inappropriate to maintain standing protocols. The selection of restraint should be individualized, and the least restrictive method is preferred; for instance, it is not necessary to restrain an agitated elderly patient with dementia in the same manner as an aggressive, muscular patient with cocaine intoxication. Hospitals must provide adequate training such that competent staff members are available for the safe application of physical restraint at all times.

Box 195.2

Guidelines for the Application of Physical Restraint

Protect the patient’s rights, dignity, and well-being.

Use of restraint is assessment driven.

Use the least restrictive method.

Trained, competent staff should provide safe application of restraint.

A time-limited order must be noted on the chart.

Document why restraint is necessary—be specific.

Act in the best interests of the patient.

Use restraints to facilitate medical evaluation or treatment.

Nursing documentation should be very thorough.

Monitoring and reassessment of the patient’s clinical condition and needs are essential.

Adapted from The Joint Commission: 2006-2007. Comprehensive accreditation manual for behavioral health care. Oakbrook Terrace, Ill: Joint Commission Resources; 2006.

Documentation

Documentation differs for physicians and for nursing staff. A time-limited order for restraints must be written on the chart before or shortly after restraints are applied. Providers must document why physical restraints were necessary and must cite that verbal techniques failed to calm the patient. Be specific about the patient’s condition and reasons for restraint, including potential danger to the patient or others, the planned medical evaluation or treatment, and assessment of the patient’s decision-making capacity. Nursing responsibilities include monitoring, frequent reassessment, and documentation of the patient’s condition and personal needs. The advent of electronic medical records and computerized physician order entry presents an opportunity to direct documentation that better meets regulatory requirements.8

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Restraint*

Physician

Document why physical or chemical restraint was chosen and necessary. Cite that verbal techniques failed to calm the patient.

Record specific information about the patient’s arrival, the reasons for restraint, the potential danger to self or others, the planned medical evaluation, and an assessment of the patient’s decision-making capacity.

Record the initial evaluation by a licensed, independent provider within 1 hour of the patient’s arrival and restraint.

A time-limited order should be charted within 1 hour of the patient’s arrival.

Update restraint orders every 4 hours for adults, 2 hours for adolescents aged 9 to 17 years, and 1 hour for children younger than 9 years.9

Nursing

* Refer to www.jointcommission.org for more information.

Technique

Safe application of physical restraint is best achieved through systematic, consistent, protocol-driven techniques (Box 195.3). Many hospitals have a restraint team of at least five members who respond to the bedside when called by any provider. One staff member should lead the restraint team, which usually consists of nurses, medical assistants, and security personnel. Ideally, physician involvement in restraint is minimized in an effort to preserve the physician-patient relationship as much as possible. Physicians are held responsible for the negligent application of restraint, however, so they should limit their involvement only if another experienced team member is available to lead the restraint team.

Positioning

Restraint position may be changed depending on the patient’s clinical status and the needs of the staff. Restraining a patient in the supine position is more comfortable for the patient and allows greater ease of examination. Patients with an increased risk for aspiration should be restrained on their side. Patients should not be restrained in a “hog-tied” position (Fig. 195.1).

Agitated patients are able to generate significant force and momentum and have been known to overturn gurneys if they are not restrained in the proper position. If all four limbs are to be restrained, the patient should have one arm up and one arm down. When only two limbs are restrained, the contralateral arm and leg should be restrained. It is more difficult to generate enough force to overturn a gurney in these positions (Fig. 195.2).

Complications

Abrasions and bruising account for the majority of complications resulting from restraint.10 However, serious complications and death can occur if restraints are applied inappropriately or the patient is not adequately monitored.

One small subset of physically restrained patients, usually accompanied by law enforcement, suffers cardiac arrest shortly before or after arrival at the ED. For many years their demise was attributed to positional asphyxia related to the prone or hobble position.11 Positional asphyxia results from an alteration in respiratory mechanics with ensuing decreased pulmonary function and increased cardiac output caused by the patient’s position. This change in pulmonary function is not clinically relevant in normal volunteers subjected to prone restraint, however. More recent studies have found that factors related to the excited delirium are more likely to contribute to sudden death in these restrained individuals. Protracted struggle against physical restraint by patients with altered pain sensation may complicate or lead to hyperthermia, increased sympathetic tone with vasoconstriction, and release of lactic acid from prolonged isotonic muscle contractions. Profound metabolic acidosis is associated with cardiovascular collapse in many restraint-related deaths.12 Cocaine and other sympathomimetic intoxications are frequently seen in this patient population.

Chemical Restraint, Anxiolysis, and Sedation

Rationale

Many patients with a history of chronic psychiatric conditions know, accurately, that they have the right to refuse antipsychotic medication in nonemergency settings. However, this right does not extend to patients who are acutely combative and in whom violent behavior threatens life or limb by failure to become calm through verbal or physical means.13 Although it is difficult to accurately predict the cause of agitated behavior, the choice of chemical restraint agent should be tailored to the suspected cause of agitation, the optimal duration of sedation, and the depth of sedation needed.

Butyrophenones

Butyrophenones (haloperidol and droperidol) constitute the main class of typical antipsychotic medications recommended for an undifferentiated patient with acute agitation in the ED.14 The butyrophenones are considered high-potency antipsychotic agents because of their strong affinity for the dopamine 2 (D2) receptor in comparison with other typical antipsychotic agents. As a result of this affinity, the butyrophenones are more effective, cause less hypotension, and have fewer anticholinergic effects than older agents do.

Absolute contraindications to the use of butyrophenones include allergy to this class of drugs, anticholinergic drug intoxication, and a history of Parkinson disease. Relative contraindications include pregnancy, lactation, and hypovolemia. Butyrophenones are widely reported to decrease the seizure threshold, yet no conclusive evidence supports this observation, particularly in patients with sympathomimetic use.15

The most common complications of the use of butyrophenones are related to extrapyramidal symptoms, which occur in less than 10% of patients within the first 24 hours of ED care. Dystonic reactions and akathisia are the most common manifestations of extrapyramidal symptoms requiring treatment in the ED. Akathisia is frequently misdiagnosed as psychiatric decompensation when it is manifested as restlessness, pacing, tension, and irritability.16 Extrapyramidal symptoms are treated with either benztropine (Cogentin), 2 mg, or diphenhydramine (Benadryl), 50 mg, intramuscularly or intravenously. Doses may be repeated every 5 minutes up to three times. Relief is rapid and dramatic in most cases. Benzodiazepines may be added for patients who do not respond initially. Many international providers use haloperidol in combination with promethazine because of its antihistamine and sedating properties. Studies show that this combination provides deeper sedation and requires less additional medication at 4 hours than an atypical antipsychotic does alone.17

As with other neuroleptic agents, neuroleptic malignant syndrome has been reported with the use of butyrophenones (Table 195.1). This potentially fatal complex of autonomic instability is marked by high fever, muscle rigidity, and altered mental status. Aggressive symptomatic treatment includes cooling, benzodiazepines, dantrolene, and discontinuation of the offending agent.18

Table 195.1 Managing Acute Complications of Sedation with Antipsychotic Agents

| PROBLEM | TREATMENT |

|---|---|

| Acute dystonic reaction |

Monitor closely for signs of NMS

Add a benzodiazepine for sedation

Discontinue antipsychotic medication

Add a benzodiazepine for sedation

Consider neuromuscular blockade (paralysis) if temperature >40° C

Institute aggressive hydration and alkalinization of urine to prevent renal failure from rhabdomyolysis

Dantrolene indicated for malignant hyperthermia but of unproven clinical benefit for NMS

bid, Twice daily; IM, intramuscularly; IV, intravenously; NMS, neuroleptic malignant syndrome; PO, orally; qd, once daily; qid, four times daily; tid, three times daily.

Haloperidol (Haldol)

Haloperidol may be given in 2.5- to 10-mg increments at 30- to 60-minute intervals for adults. Its onset of action is between 15 and 30 minutes and its duration is 4 hours. Although a dosage ceiling has not been established, it is unusual to require more than three doses to achieve adequate sedation for an acute episode. It is rare to administer more than 60 mg in a 24-hour period.19

Though uncommon, the use of haloperidol in violent pediatric patients is well described. The pediatric dose of haloperidol is 0.075 mg/kg/day, repeated up to every hour (orally) or every 30 minutes (intramuscularly) at a dose of up to 2 mg/day in patients younger than 12 years. Of note, younger children are at greater risk for extrapyramidal symptoms than adolescents are because of increased D2 receptor activity at younger ages.20,21

Haloperidol remains an effective and inexpensive option for the treatment of acute aggression. It is well tolerated if coadministered with an anticholinergic agent.20

Droperidol (Inapsine)

Droperidol has a long history of use for the treatment of acute agitation in the ED. Studies have shown the superiority of droperidol over haloperidol within the first 30 minutes of intramuscular administration. The FDA issued a “black box” warning for droperidol in 2001, however, because of the risk for QT prolongation and ventricular dysrhythmias causing sudden cardiac death. Some authors analyzed the case records cited by the FDA and presented cogent arguments supporting continued use of this drug; these investigators questioned the reasoning behind the “black box” warning.22–24 Administration of droperidol for the treatment of violent patients and migraine headaches is now considered an off-label use of the drug. Droperidol is still approved for intravenous administration to prevent and treat postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Droperidol may be given in 2.5- to 5-mg increments intravenously at 15-minute intervals for adults. The intramuscular dose is 5 to 10 mg. Its onset of action is between 3 and 10 minutes. More than two doses are rarely required to achieve adequate sedation for an acute episode. The time to arousal is approximately 2 hours.19 Droperidol was found to produce more consistent moderate sedation than occurs with midazolam and the combination of droperidol and midazolam together.

Conduction abnormalities can develop with the administration of butyrophenones in high doses. The FDA “black box” warning for droperidol also referred to some cases of conduction abnormalities at low doses. Experts recommend obtaining an electrocardiogram before administering droperidol to patients in the ED, a recommendation that is impractical with an acutely agitated or violent patient. Although many authors disagree with the conclusions of the FDA, it is prudent to avoid the use of butyrophenones in elderly patients, critically ill patients, or patients with known preexisting heart disease.18

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are preferred first-line agents for the acute management of agitation.12 Benzodiazepines are particularly useful for agitation caused by the ingestion of sympathomimetic agents and alcohol withdrawal. Sedation and mild respiratory depression are the most prominent side effects of benzodiazepines. Therefore, these drugs are quite safe in patients with most medical comorbid conditions. Lorazepam and midazolam are the two prototypic benzodiazepines used for the treatment of violent patients in the ED.

Lorazepam (Ativan)

Observational studies have reported that lorazepam is at least as effective as haloperidol in treating patients with acute agitation. Lorazepam is given in 0.5- to 2-mg increments as frequently as every 15 minutes, depending on the patient’s level of sedation and respiratory status. Intramuscular injection is the most common route of administration and is quite reliable. Lorazepam has a shorter half-life than some parenteral benzodiazepines and lacks active metabolites. Lorazepam may also be given intravenously, orally, and sublingually. The time of onset after intravenous or intramuscular injection is between 15 and 30 minutes, and the drug’s effect lasts more than 3 hours. Sublingual or oral administration of lorazepam is a viable alternative route for patients who are cooperative and would benefit from rapid relief of anxiety (Table 195.2). Lorazepam is classified as a class D agent in pregnancy and thus should be avoided in pregnant and lactating women. Pediatric dosing of lorazepam is 0.05 mg/kg with doses of 0.5 to 2 mg orally or intramuscularly. Onset is 30 minutes orally and 15 minutes intramuscularly. The duration of effect is 6 hours orally or intramuscularly.20

Table 195.2 Medication Recommendations for Patients Willing to Take Oral Medications

| CLINICAL SCENARIO | RECOMMENDED ORAL MEDICATION |

|---|---|

| No information on past history | Lorazepam |

| Psychosis in the past; delirium or dementia | Risperidone |

| Cardiac arrhythmias or conduction defects | Lorazepam |

| Diabetes or hyperglycemia | Lorazepam and haloperidol, ziprasidone |

| Obesity | Lorazepam |

| Pediatric ages | Haloperidol, lorazepam, atypical antipsychotic agents, antihistamines |

Midazolam (Versed)

Midazolam is particularly beneficial if rapid sedation is required and prolonged sedation is less important. The first ED study describing midazolam for this indication used an intramuscular dose of 5 mg, which provided rapid sedation with a mean time to onset of 18 minutes and arousal at a mean time of 82 minutes.25 Another study reported the effective sedation time to be 45 minutes for midazolam and more than 2 hours for other agents.26 Fewer cardiorespiratory effects are seen with the intramuscular administration of midazolam; most authors have reported no difference in vital signs or oxygen saturation in comparison with other agents used to sedate agitated or violent patients when the 5-mg dose was administered.20,25 However, other authors have reported increased respiratory depression in patients suffering from alcohol intoxication.27 The intramuscular dose should be decreased by half in elderly patients or when midazolam is used in combination with opioid agents. Larger doses of midazolam (e.g., 10 to 15 mg intramuscularly) result in greater need for airway adjuncts.28

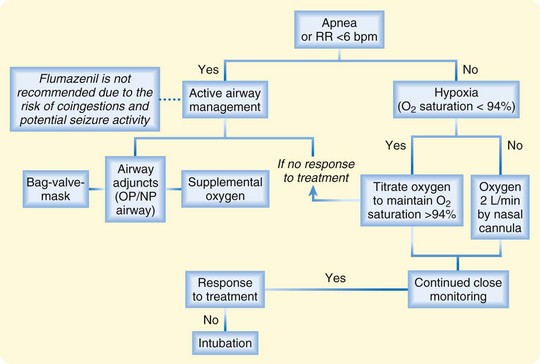

Treatment of oversedation and respiratory depression from the use of benzodiazepines in agitated or violent patients is supportive care (Fig. 195.3). Supplemental oxygen, repositioning, and airway adjuncts such as nasal trumpets suffice in most cases. Active airway management, including jaw thrusts, use of bag-valve-mask ventilation, or endotracheal intubation, is rarely necessary. It is prudent to avoid the use of flumazenil (Romazicon) because of the frequency of epileptogenic coingestion and the use of combination therapy with butyrophenones.

Combination Therapy

The combination of lorazepam, 2 mg, and haloperidol, 5 mg, for sedation of agitated psychotic patients was found to be superior to either agent alone when investigators considered the speed of sedation and frequency of side effects. The duration of sedation was longer in patients receiving combination therapy.29 Lorazepam, haloperidol, and benztropine (Cogentin, 1 mg) can be administered in the same intramuscular syringe.

Atypical Antipsychotic Medications

Ziprasidone (Geodon)

Ziprasidone is approved for the treatment of acute agitation in schizophrenic and bipolar/manic patients. Ziprasidone has not been extensively studied in patients with undifferentiated causes of agitation in the ED. The typical dose is 10 mg intramuscularly every 2 hours or 20 mg intramuscularly every 4 hours. Ziprasidone is associated with the greatest change in the QT interval of the atypical antipsychotics, comparable with the QT prolongation seen with haloperidol. In addition, ziprasidone needs to be diluted and is not as readily available for use as other agents.16 No dosing information is available for the use of ziprasidone in children with agitation, but the drug is used for the treatment of Tourette syndrome at a dose of 5 to 40 mg/day.26

Olanzapine (Zyprexa)

Olanzapine is also approved for the treatment of acute agitation in schizophrenic and bipolar/manic patients in the ED. Olanzapine is available in either an intramuscular or oral disintegrating tablet formulation at 5 to 10 mg. Olanzapine is strongly sedating and demonstrates 160 times the antihistamine potency of diphenhydramine. Olanzapine causes the smallest change in QT interval of the atypical antipsychotics. Long-term use of the drug is associated with weight gain and hyperglycemia.26 The manufacturer does not recommend the combination of intramuscular olanzapine with a parenteral benzodiazepine. Olanzapine has been approved for use in children at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg. Children younger than 12 years may receive 2.5 mg orally or intramuscularly. Children older than 12 years may be administered the adult dose. Its onset of action is 30 minutes orally and 10 to 20 minutes intramuscularly, with a duration of action of up to 24 hours.20

Risperidone (Risperdal)

Risperidone is equivalent to haloperidol for the treatment of psychosis, and it is possibly more effective in treating aggressive behavior. Risperidone may be administered orally in the ED as a liquid formulation or as a rapidly disintegrating tablet at a dose of 1 to 3 mg. Although both methods of oral administration are easier with a cooperative patient, the liquid formulation can be mixed in a beverage or administered orally by syringe to resistant patients. The mean time until sleep was 43 minutes in one study. Risperidone has fewer anticholinergic properties, thus resulting in less confusion and sedation than with other atypical antipsychotic agents. Pediatric dosing of risperidone is 0.025 to 0.05 mg/kg. Children younger than 12 years may receive a dose of 0.25 to 0.5 mg orally. Pubertal pediatric patients may be administered a dose of 0.5 to 1 mg orally. Doses may be repeated two to four times until sedated. Its onset of action is 30 minutes with a peak concentration in 1 to 2 hours.20

Aripiprazole (Abilify)

Aripiprazole is approved for the treatment of acute agitation in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar mania. It is available as a 9.75-mg intramuscular injection and may be repeated every 2 hours. Doses should not exceed more than 30 mg/day. Aripiprazole is equivalent to haloperidol with regard to control of agitation without oversedation.16 An oral dose of 2 mg is recommended for pediatric patients because of autism-related irritability or bipolar mania.

Tips and Tricks

Violence rarely erupts without warning.

Avoid the “us versus them” mentality: Unprofessional staff behavior can elicit violent eruptions by patients.

R-E-S-P-E-C-T goes a long way toward helping patients regain their composure.

Be aware of your own reactions: You can make the situation worse.

“GOT IVS”: The seven do-not-forget reversible causes of altered metal status and violent behavior:

Document, document, document: If restraint is the right thing to do, be sure to say why.

Different situations require different medications and treatment; one drug is not good for all circumstances, so tailor your treatment to the situation.

Allen MH, Currier GW, Carpenter D, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: treatment of behavior emergencies 2005. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11(Suppl 1):6–108.

Hill S, Petit J. The violent patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2000;18:301–315.

Marco CA, Vaughan J. Emergency management of agitation in schizophrenia. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:767–776.

Sorrentino A. Chemical restraints for the agitated, violent, or psychotic pediatric patient in the emergency department: controversies and recommendations. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2004;16:201–205.

Zun LS. A prospective study of the complication rate of use of patient restraint in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2003;24:119–124.

1 Lion JR, Snyder W, Merrill G. Under-reporting of assaults on staff in a state hospital. Hosp Commun Psychiatry. 1981;32:497–498.

2 Mahoney BS. The extent, nature and response to victimization of emergency nurses in Pennsylvania. J Emerg Med Nurs. 1991;17:282–291.

3 National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Violence: occupational hazards in hospitals. NIOSH publication 2002-101. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2002-101/, 2011. Accessed February 1

4 Lavoie FW, Carter GL, Danzl DF, et al. Emergency department violence in United States teaching hospitals. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:1227–1233.

5 Beck JC, White KA, Gage B. Emergency psychiatric assessment of violence. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1562–1565.

6 Blanchard JC, Curtis KM. Violence in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1999;17:717–731.

7 Annas GJ. The last resort: the use of physical restraints in medical emergencies. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1408–1412.

8 Bisantz A, Wears R. Forcing functions: the need for restraint. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:477–479.

9 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Medicare and Medicaid programs; hospital conditions of participation: patients’ rights. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2006;71(236):71377–71428.

10 Zun LS. A prospective study of the complication rate of use of patient restraint in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2003;24:119–124.

11 Chan TC, Vilke GM, Neuman T, et al. Restraint position and positional asphyxia. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30:578–586.

12 Hick JL, Smith SW, Lynch MT. Metabolic acidosis in restraint-associated cardiac arrest: a case series. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:239–243.

13 Hill S, Petit J. The violent patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2000;18:301–315.

14 Allen MH, Currier GW, Carpenter D, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: treatment of behavior emergencies 2005. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11(Suppl 1):6–108.

15 Branney SW, Colwell CB, Aschbrenner JK, et al. Safety of droperidol for sedating out-of-control ED patients. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3:527.

16 Lindenmayer JP, Kanellopoulou I. Schizophrenia with impulsive and aggressive behaviors. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2009;32:885–902.

17 Raveendran NS, Tharyan P, Alexander J, et al. Rapid tranquillisation in psychiatric emergency settings in India: pragmatic randomised controlled trial of intramuscular olanzapine versus intramuscular haloperidol plus promethazine. BMJ. 2007;335(7625):865.

18 Marco CA, Vaughan J. Emergency management of agitation in schizophrenia. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:767–776.

19 Dubin WR, Feld JA. Rapid tranquilization of the violent patient. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7:313–320.

20 Adimando AJ, Poncin YB, Baum CR. Pharmacological management of the agitated pediatric patient. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26:856–860.

21 Sorrentino A. Chemical restraints for the agitated, violent, or psychotic pediatric patient in the emergency department: controversies and recommendations. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2004;16:201–205.

22 Chase PB, Biros MH. A retrospective review of the use and safety of droperidol in a large, high-risk, inner-city emergency department patient population. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1402–1410.

23 Kao LW, Kirk MA, Evers SJ, et al. Droperidol, QT prolongation, and sudden death: what is the evidence? Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:546–548.

24 Van Zwieten Z, Mullins ME, Jang T. Droperidol and the black box warning. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:139–140.

25 Nobay F, Simon BC, Levitt MA, et al. A prospective, double-blind, randomized trial of midazolam versus haloperidol versus lorazepam in the chemical restraint of violent and severely agitated patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:744–749.

26 Martel M, Sterzinger A, Miner J, et al. Management of acute undifferentiated agitation in the emergency department: a randomized double-blind trial of droperidol, ziprasidone, and midazolam. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1167–1172.

27 Isbister GK, Calver LA, Page CB, et al. Randomized controlled trial of intramuscular droperidol versus midazolam for violence and acute behavioral disturbance: the DORM study. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:392–401.

28 Spain D, Crilly J, Whyte I, et al. Safety and effectiveness of high-dose midazolam for severe behavioural disturbance in an emergency department with suspected psychostimulant-affected patients. Emerg Med Australas. 2008;20:112–120.

29 Battaglia J, Moss S, Rush J, et al. Haloperidol, lorazepam, or both for psychotic agitation? A multicenter, prospective, double-blind, emergency department study. Am J Emerg Med. 1997;15:335–340.