94 Altered Mental Status and Coma

• Because the differential diagnosis of coma is broad, a systematic approach to patient evaluation and diagnostic testing is required.

• Patients with altered mental status may have subtle neurologic dysfunction, so careful neurologic examination is necessary.

• Quickly reversible causes should be sought before the initiation of a more lengthy diagnostic work-up. Naloxone, dextrose, and thiamine administration should be considered initially in patients with undifferentiated coma.

• Structural brain lesions that may require operative intervention dictate immediate consultation with a neurosurgical service.

Pathophysiology

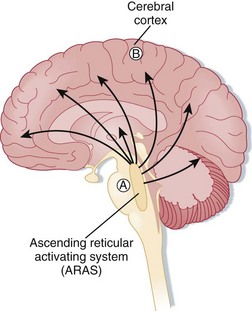

Coma can be caused by damage to the brainstem (Fig. 94.1), the cerebral cortex, or both. These structures are vulnerable to toxins, metabolic derangements, and mechanical injury. Localized, unilateral lesions in the cerebral cortex do not usually induce altered mental status or coma, even with other cognitive functions being impaired. However, if both cerebral hemispheres are affected, altered mental status or coma can occur, depending on the size of the insult and its speed of progression. The ascending reticular activating system can also be vulnerable to small, focal lesions in the brainstem, which can result in coma.1,2

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Regardless of the circumstance, the EP will frequently need to use alternative sources of information to answer key historical questions that may alter the breadth and speed of the diagnostic work-up undertaken. Common sources of information include family members, neighbors, prehospital personnel, law enforcement, and nursing home staff.3 They may know of preceding symptoms such as headache, nausea, vomiting, or fever. It is important to determine the rate of symptom onset and whether the patient had any history of trauma, exposure to drugs or toxins, or new medications or change in dosage. Family members usually have some knowledge regarding the patient’s past medical history. Additionally, previous medical records should be reviewed whenever possible to confirm or augment the information provided. If the patient’s historical baseline mental status cannot be established, the current findings must be assumed to be an acute change.4

The age of the patient can be a key historical tool that may focus the physician on the most probable cause of the patient’s symptoms (Box 94.1).

In infants, infectious causes of altered mental status are most common; however, nonaccidental trauma and metabolic derangements from inborn errors of metabolism are also possible causes.5 Toxic ingestions are commonly seen in young children. Adolescents and young adults are often seen in the ED after recreational drug use. The elderly are particularly susceptible to infectious causes and to disorders related to changes in medications or drug doses, use of over-the-counter medications, and alterations in their living environment. Psychiatric illness should be considered in the adolescent through elderly population and must be distinguished from medical illness as a cause of the patient’s symptoms.

As with all patients, specific attention should first be paid to assessment of the ABCs and specific vital signs. Alterations in respiratory patterns such as hyperventilation, Kussmaul or Cheyne-Stokes breathing, agonal breathing, or apnea should be noted and may suggest toxic or metabolic derangements or primary central nervous system abnormalities. Marked hypotension or hypertension should be addressed immediately even if the underlying cause is unknown. Bradycardia may be the result of increased intracranial pressure as seen in the Cushing response and suggests a state of hypoperfusion. Tachycardia may also result in hypoperfusion and can be the result of toxic, metabolic, or primary cardiac causes. Assessment of temperature is crucial because both hypothermia and hyperthermia can cause altered mental status from infectious, structural (Box 94.2), environmental exposure, or toxic or metabolic causes (Box 94.3).

Box 94.3 Metabolic and Systemic Causes of Altered Mental Status and Coma

Neurologic Evaluation

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) can be used to assess the patient’s level of consciousness. The GCS does not differentiate between causes of altered mental status or coma or assess cognition. However, it is useful in monitoring changes in mental status when serial examinations are performed and serves as an objective reference when communicating with consultants (Table 94.1).6

| SCORE | ||

|---|---|---|

| Eye opening | Spontaneous | 4 |

| To voice | 3 | |

| To pain | 2 | |

| None | 1 | |

| Verbal response | ||

| Adult | Oriented | 5 |

| Confused | 4 | |

| Inappropriate words | 3 | |

| Incomprehensible words | 2 | |

| None | 1 | |

| Pediatric | Appropriate | 5 |

| Cries, consolable | 4 | |

| Persistently irritable | 3 | |

| Restless, agitated | 2 | |

| None | 1 | |

| Motor response | Obeys commands | 6 |

| Localizes pain | 5 | |

| Withdraws to pain | 4 | |

| Flexion to pain | 3 | |

| Extension to pain | 2 | |

| None | 1 | |

| Maximum score | 15 | |

A focal neurologic deficit usually suggests a structural cause. Pupillary findings such as unilateral dilation or a “blown pupil” and loss of reactivity indicate uncal herniation, which is a neurosurgical emergency. Funduscopic examination can demonstrate hemorrhage in the setting of trauma or papilledema, which suggests increased intracranial pressure.2

Testing of eye movements is a hallmark in the neurologic examination of patients with altered mental status or coma. Eye movements are coordinated by ocular centers in the cerebral cortex and the medial longitudinal fasciculus located in the brainstem. The extraocular muscles are innervated primarily by cranial nerves III, IV, and VI. Disconjugate gaze in the horizontal plane is common and can be associated with sedated or drowsy states or alcohol intoxication. Disconjugate gaze in the vertical plane is more ominous and points to pontine or cerebellar lesions. A persistently adducted eye is caused by cranial nerve VI paresis, whereas a persistently abducted eye is caused by cranial nerve III paresis. These are nonlocalizing lesions; however, elevated intracranial pressure or mass effects from trauma, for example, can compromise cranial nerve functions via extrinsic compression. In the absence of contraindications, oculocephalic (doll’s eyes) or oculovestibular reflex testing can be very helpful. If intact, these reflexes demonstrate functional integrity of a significant majority of the brainstem, thus making it exceedingly unlikely as the anatomic location for the cause of the patient’s altered mental status.1,2,5,7

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The differential diagnosis of altered mental status and coma is extensive and can be daunting for the busy EP (see Boxes 94.1 to 94.3). Fortunately, there are many distinguishing features in the physical examination that, when combined with information gleaned from the patient’s history of the present illness, past medical history, and response to therapy (i.e., dextrose, naloxone), point to a particular cause and are frequently of greater diagnostic value than imaging, electrocardiograms (ECGs), and laboratory tests.1 However, a systematic approach is best and reduces the likelihood of missing an important clue.1,2,8

Diagnostic Testing

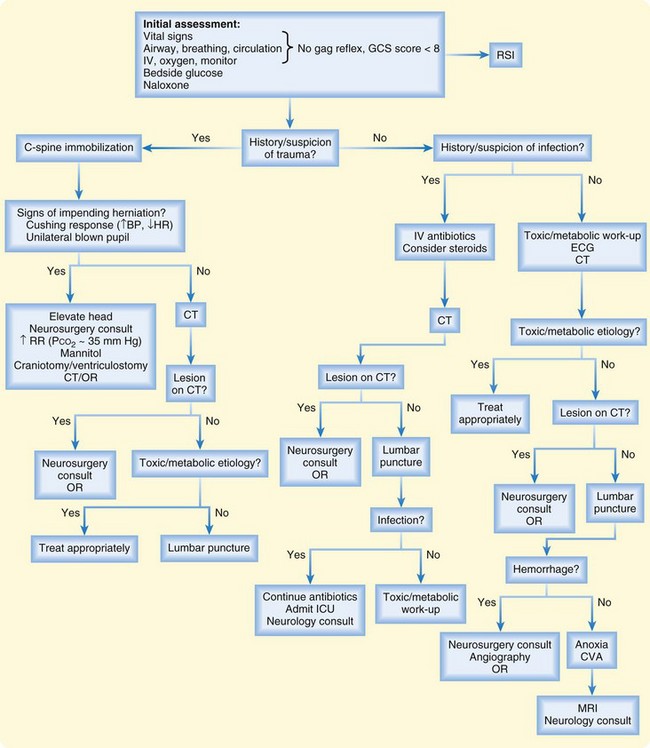

Diagnostic testing in patients with altered mental status or coma is based on information gathered from the history and physical examination, which in most cases will point toward a structural versus systemic or metabolic cause. Extensive metabolic work-ups should not precede neuroimaging studies in patients with altered mental status or coma that may be due to structural causes. Similarly, treatment of suspected narcotic overdose or hypoglycemia should not be delayed in favor of imaging studies. However, in undifferentiated patients, diagnostic tests should be performed in parallel whenever possible to avoid unnecessary delays in initiating treatment. A general approach to the diagnostic work-up of patients with altered mental status or coma is shown in Figure 94.2.

Laboratory Evaluation

A complete blood cell count may demonstrate profound anemia from witnessed or occult blood loss. A low white blood cell count raises concern for an immunocompromised state, but an elevated white blood cell count is less helpful in making the diagnosis as a nonspecific marker for infection, inflammation, or stress. Low platelet levels may indicate sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, or intracranial bleeding. Serum coagulation studies may be performed to look for bleeding dyscrasias or supratherapeutic levels of anticoagulants (warfarin) or, when combined with other liver function studies, may provide evidence of liver dysfunction. Both platelet counts and coagulation studies should be performed before obtaining central venous access and performing lumbar puncture or other invasive procedures if time or the patient’s condition allows. Checking the serum ammonia level is controversial; it has not been shown to be a reliable marker for the cause of altered mental status because it can be normal in patients with hepatic encephalopathy but can also be elevated in those with acute hepatic failure from other causes, as well as valproic acid toxicity and inborn errors of metabolism.9

Imaging

A limitation of brain CT scanning is the potential poor view of the posterior fossa as a result of linear artifacts created by the thick skull base. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is more helpful in identifying structural lesions in this area; however, its cost and limited availability, as well as the inability to monitor unstable patients, make this imaging modality less feasible in some ED settings.4 CT angiography or venography may be available for the diagnosis or treatment (or both) of vertebral or basilar artery stenosis or occlusion, intracerebral aneurysms, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, or arteriovenous malformations. If brain abscess or metastatic lesions are a concern, contrast-enhanced head CT can be useful in making the diagnosis.

Treatment

In the setting of suspected toxic ingestion, activated charcoal with or without sorbitol is indicated. Gastric lavage has been used in patients with recent (less than 60 minutes since ingestion), potentially lethal toxic ingestion (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants, beta-blockers); however, this intervention is somewhat controversial and associated with potential complications, including aspiration and esophageal damage. Specific antidotes, if applicable based on the history and physical examination, should be initiated early. Finally, early hemodialysis should be considered in patients who have ingested substances amenable to this therapeutic modality.10

American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy for the initial approach to patients presenting with altered mental status. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:251–281.

Feske SK. Coma and confusional states: emergency diagnosis and management. Neurol Clin. 1998;16:237–256.

Hoffman R, Goldfrank L. The poisoned patient with altered consciousness. JAMA. 1995;274:562–569.

Kanich W, Brady WJ, Huff JS, et al. Altered mental status: evaluation and etiology in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:613–617.

Koita J, Riggio S, Jagoda A. The mental status examination in emergency practice. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:439–451.

1 Plum F, Posner J. The diagnosis of stupor and coma, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 1980.

2 Bateman DE. Neurological assessment of coma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:13–17.

3 Kanich W, Brady WJ, Huff JS, et al. Altered mental status: evaluation and etiology in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:613–617.

4 American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy for the initial approach to patients presenting with altered mental status. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:251–281.

5 Kirkham FJ. Non-traumatic coma in children. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85:303–312.

6 Koita J, Riggio S, Jagoda A. The mental status examination in emergency practice. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:439–451.

7 Devuyst G, Bogousslavsky J, Meuli R, et al. Stroke or transient ischemic attacks with basilar artery stenosis or occlusion. Arch Neurol. 2002;9:567–573.

8 Feske SK. Coma and confusional states: emergency diagnosis and management. Neurol Clin. 1998;16:237–256.

9 Elgouhari HM, O’Shea R. What is the utility of measuring the serum ammonia level in patients with altered mental status? Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76:252–254.

10 Hoffman R, Goldfrank L. The poisoned patient with altered consciousness. JAMA. 1995;274:562–569.