37 Wilson Disease

Clinical Presentation

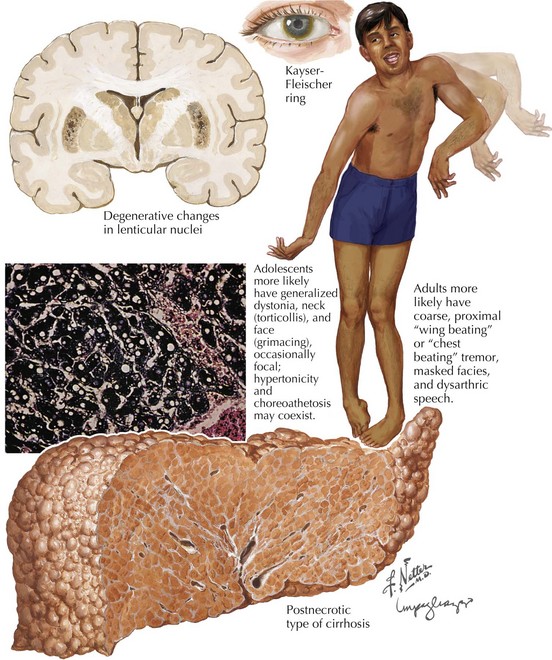

The subcortical nervous system is particularly sensitive to the free-ranging excess copper. Approximately 60% of WD patients present with a neurologic disorder (Box 37-1). Often they do not present until young adulthood with a variety of neurologic manifestations, including dysarthria, tremor, dysphagia, bradykinesia, and behavioral disturbance. Speech manifestations vary from rapid articulation to hypophonia and dysarthria. Any young adult patient who develops unexplained speech impairment needs to be evaluated for WD.

Box 37-1 Clinical Consideration for Diagnosis of Wilson Disease

Ophthalmologic manifestations are not only common in WD but also are often crucial to a specific diagnosis. The classic and best-known finding is the dull, yellow-brown pigment at the limbus of the cornea. These are known as KF rings. They (Fig. 37-1) are most dense at the upper and lower poles of the cornea. These result from copper deposition in the Descemet membrane at the limbus of the cornea. KF rings are present in nearly all patients with WD who present primarily with neurologic or psychiatric symptoms. However, the uninitiated physician must maintain a level of clinical suspicion, or the actual identification of these KF rings may be missed on casual examination. This is particularly noticeable in the majority of patients as brown irises are the most common, providing a means for the copper deposition to inconspicuously blend into the human landscape. It is here that our ophthalmologic colleagues provide a major diagnostic keystone. Slit-lamp examination is often absolutely necessary for detection and verification. Early on KF rings are often absent in the asymptomatic individuals and in up to 50% of persons having a hepatic presentation. Other abnormal ophthalmologic signs include reduced saccadic velocity, interruption of smooth pursuit by saccadic intrusions, and sunflower cataracts (15–20% of patients).

Diagnosis

Early diagnosis of WD is crucial to effective treatment and potential for a cure. This most depends on astute clinical collation in reference to the sometimes vague signs and symptoms (Box 37-1 and Fig. 37-1). This diagnosis should always be considered in patients between 10 and 40 years old who have unexplained dysarthria or tremor or psychiatric or hepatic disease. Devastating neurologic and hepatic deterioration may be prevented with early diagnosis and treatment.

Ceruloplasmin levels are reduced in patients with WD, often with levels below 20 mg/dL (Box 37-2). A serum ceruloplasmin value less than 20 mg/dL and concomitant slit-lamp definition of a KF ring are diagnostic of WD. In acute liver damage, ceruloplasmin levels may be normal because it is an acute-phase reactant; therefore, a low ceruloplasmin concentration is not an absolute diagnostic test; this may also be seen in hypoproteinemic states.

Daily urinary copper excretion is elevated in WD patients. Its measurement provides a means to monitor the effectiveness of therapy. An elevated non-ceruloplasmin component of plasma copper is increased, filtered by the glomerulus, and incompletely reabsorbed by the renal tubules, causing urinary excretion of copper. The increased renal copper excretion does not adequately compensate for the reduced biliary copper excretion. Measurement of 24-hour copper excretion is a standardized and reliable diagnostic test and is often greater than 100 µg (Box 37-2).

Ala A, Walker AP, Ashkan K, et al. Wilson’s disease. Lancet. 2007;369:397-408. Excellent overview

Glazebrook AJ. Wilson’s disease. Edinb Med J. 1945;52:83-87. Another historical milestone

Merle U, Schaefer M, Ferenci P, et al. Outcome of Wilson’s disease: a cohort study Clinical presentation, diagnosis and long-term outlook. Gut. 2007;56:115-120. An overview

Pabón V, Dumortier J, Gincul R, et al. Long-term results of liver transplantation for Wilson’s disease. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008 Apr;32(4):378-381.

Pfeiffer RF. Wilson’s Disease. Semin Neurol. 2007 Apr;27(2):123-132. A state-of-the-art neurologic review

Scheinberg IH, Gitlin D. Deficiency of ceruloplasmin in patients with hepatolenticular degeneration (Wilson’s disease). Science. 1952;116:484.

Scheinberg IH, Jaffe ME, Sternlieb I. The use of trientine in preventing the effects of interrupting penicillamine therapy in Wilson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:209-213.

Sinha S, Taly AB, Ravishankar S, et al. Wilson’s disease: cranial MRI observations and clinical correlation. Neuroradiology. 2006;48:613-621.

Steindl P, Ferenci P, Dienes HP, et al. Wilson’s disease in patients presenting with liver disease—a diagnostic challenge. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:212.

Walshe JM. Wilson’s disease; new oral therapy. Lancet. 1956;267(6906):25-26.

Wilson SAK. Progressive lenticular degeneration: a familial nervous disease associated with cirrhosis of the liver. Brain. 1912;34:20-509. The classic clinical definition