28 Dysthymia

Clinical Presentation

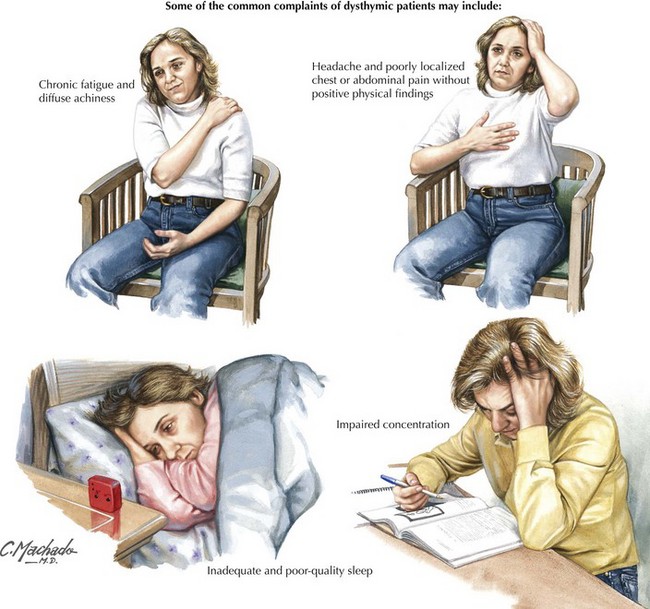

Dysthymic patients have fewer and less-intense depressive symptoms than patients with major depression. To establish the diagnosis, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) requires at least a 2-year course of predominantly depressed mood, while noting that chronic low mood may be such a fixture of the patient’s life as to be unrecognized by the patient. Two other symptoms must also be present from a list, including sleep disturbance, appetite disturbance, fatigue, hopelessness, low self-esteem, and impaired concentration (Fig. 28-1). Dysthymia usually has an early and insidious onset and a chronic course. Family history of mood disorder is common.

Gureje O. The relation between multiple pains and mental disorders: results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Pain. 2008 Mar;135(1-2):82-91.

Ratey J, Johnson C. Shadow Syndromes: The Mild Forms of Major Mental Disorders That Sabotage Us. New York, NY: Pantheon; 1997.

Shedler J, Westen D. Refining personality disorder diagnosis: Integrating science and practice. American J Psych. 2004;161:1350-1365.

Subodh BNJ, Avasthi A, Chakrabarti S. Psychosocial impact of dysthymia: A study among married patients. J Affect Disord.. 2008;109:199-204.