42 Psychogenic Movement Disorders

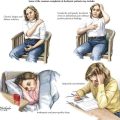

Psychogenic tremor, dystonia, myoclonus, chorea, and parkinsonism are the typical means for a functional movement disorder to present and are particularly common in women (Fig. 42-1). These patients usually have multiplicity and variability of symptoms superimposed on a significant psychiatric background. The neurologic findings do not fit a specific diagnostic set typical of the classic organic movement disorders. These factitious patients present with movements that are consistently inconsistent and are particularly liable to change or decrease during distraction. Frequently, patients with psychogenic movement disorders display uneconomic postures demonstrating a most exaggerated effort during examination that may also produce fatigue. They may demonstrate marked slowness when asked to perform certain tasks such as rapid alternating movements.

Therapeutically, psychogenic movement disorders often respond to placebo or suggestion.

Clinical Presentations

Fahn S, Williams D. Psychogenic dystonia. Adv Neurol. 1988;50:431-455.

Halle M, Fahn S, Jankovic J, et al. Psychogenic Movement Disorders. Neurology and Neurosurgery. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

Koller WC, Marjama J, Troster A. Psychogenic movement disorders. In: Jankovic J, Tolosa E, editors. Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1998:859-868.