2 Who Should Have a Fetal Heart Scan

I. GENERAL INFORMATION AND BACKGROUND

B. Level II or specialized fetal anatomical ultrasound

1. Specialized ultrasound is performed when an anomaly is suspected on the basis of history or biochemical abnormalities or when the results of either the limited or standard scan suggest the presence of fetal pathology.

2. Specialized ultrasound is performed by obstetricians, perinatologists, radiologists, and sonographers who have additional expertise in obstetric ultrasound.

C. Fetal echocardiography

1. Two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiographic evaluation includes detailed assessment of the cardiac anatomy, blood flow, heart rate and rhythm, and heart function.

2. Fetal echo is performed in pregnancies at risk for or with suspected structural, functional, or rhythm-related fetal heart disease.

3. Responsible personnel include:

a. Pediatric cardiologists with expertise in fetal and pediatric echocardiography.

b. Obstetrics or radiology personnel with training in fetal echocardiography but with assistance from pediatric cardiologists for interpretation of the findings and prenatal counseling.

II. INDICATIONS

A Maternal indications

1. Maternal metabolic disorders.

a. Type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus (preconception).

2. Maternal congenital (or familial) heart disease.

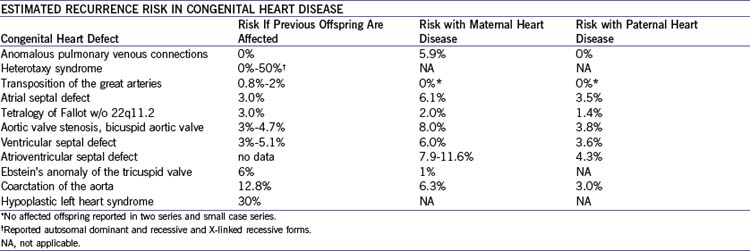

a. Congenital heart disease: Risk depends upon the specific lesion (Table 2-1) but in general ranges from 5% to 13%.

3. Maternal autoimmune disease, specifically those associated with anti-Ro or anti-La autoantibodies (4%-25% risk in affected women).

a. Fetal atrioventricular heart block typically appears after 17 weeks’ gestation in a mother with autoantibodies and with or without clinical autoimmune disease.

b. Fetal cardiomyopathy with endocardial fibroelastosis.

4. Exposure to teratogens such as:

a. Alcohol: Atrial and ventricular septal defects.

B. Fetal indications

1. Obstetric ultrasound suggesting fetal heart disease.

a. Structural cardiac pathology is the indication that has been shown to provide the highest yield for true fetal structural cardiac pathology, which provides support for the critical importance of obstetric ultrasound screening.

2. Obstetric ultrasound suggesting fetal extracardiac disease.

a. Structural pathology involving other organ systems.

b. Increased nuchal translucency in the first trimester, with a normal or abnormal karyotype.

c. Findings suggesting chromosomal abnormality or aneuploidy or documented abnormal fetal karyotype.

C. Familial indications

1. Paternal congenital heart disease (see Table 2-1).

a. Holt–Oram syndrome (autosomal dominant).

b. DiGeorge’s syndrome (22q11.2 deletion, autosomal dominant): Conotruncal cardiovascular pathology (examples below).

c. Noonan’s syndrome (autosomal dominant).

d. Williams’ syndrome (autosomal dominant).

e. Ellis–van Creveld syndrome (autosomal recessive).

f. Familial cardiomyopathy is the most common. Inheritance is autosomal dominant for both hypertrophic and dilated forms.

III. TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

A. Indications

1. Fetal echocardiography is indicated for pregnancies at risk for structural, functional, and rhythm-related fetal heart disease.

2. Indications for fetal echocardiography can be classified as maternal, fetal, and familial

3. The indication with the greatest positive yield is a finding of suspected fetal heart disease at routine fetal or obstetric ultrasound.

Abu-Sulaiman RM, Subaih B. Congenital heart disease in infants of diabetic mothers: Echocardiographic study. Pediatr Cardiol. 2004;25(2):137-140.

Ardinger RH. Genetic counseling in congenital heart disease. Pediatr Ann. 1997;26:99-104.

Boughman JA, Berg K, Astemborski JA, et al. Familial risks of congenital heart defect assessed in a population based epidemiologic study. Am J Med Gen. 1987;26:839-849.

Burn J, Brennan P, Little J, et al. Recurrence risks in offspring of adults with major heart defects: Results from first cohort of British collaborative study. Lancet. 1998;351:311-316.

Copel JA, Pilu G, Kleinman CS. Congenital heart disease and extracardiac anomalies: Associations and indications for fetal echocardiography. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;154:1121-1124.

Digilio MC, Marino B, Giannotti A, et al. Recurrence risk figures for isolated tetralogy of Fallot after screening for 22q11 microdeletion. J Med Gen. 1997;34:188-190.

Gladman G, McCrindle BW, Boutin C, Smallhorn JF. Fetal echocardiographic screening of diabetic pregnancies for congenital heart disease. Am J Perinatol. 1997;14(2):59-62.

Gladman G, Silverman ED, Law YM, et al. Fetal echocardiographic screening of pregnancies of mothers with anti-Ro and/or anti-La antibodies. Am J Perinatol. 2002;19(2):73-80.

Hyett J, Perdu M, Sharland G, et al. Using fetal nuchal translucency to screen for major congenital cardiac defects at 10-14 weeks of gestation: Population based cohort study. BMJ. 1999;318:81-85.

McAuliffe FM, Hornberger LK, Winsor S, et al. Fetal cardiac defects and increased nuchal translucency thickness: A prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(4):1486-1490.

Nicolaides KH, Brizot ML, Snijders RJM. Fetal nuchal translucency thickness: Ultrasound screening for fetal trisomy in the first trimester of pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101:782-786.

Nora JJ. From generational studies to a multilevel genetic–environmental interaction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:1468-1471.

Nora JJ, Nora AH. Update on counseling the family with a first degree relative with a congenital heart defect. Am J Med Gen. 1988;29:137-142.

Rouse B, Azen C, Koch R, et al. Maternal Phenylketonuria Collaborative Study (MPKUCS) offspring: Facial anomalies, malformations, and early neurological sequelae. Am J Med Genet. 1997;69(1):89-95.

Souka AP, Krampl E, Bakalis S, et al. Outcome of pregnancy in chromosomally normal fetuses with increased nuchal translucency in the first trimester. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;18:9-17.

Tennstedt C, Chaoui R, Korner H, Dietel M. Spectrum of congenital heart defects and extracardiac malformations associated with chromosomal abnormalities: results of a seven year necropsy study. Heart. 1999;82:34-39.