203 White Blood Cell Disorders

• White blood cell disorders are the result of cell overproduction, underproduction, or dysfunction.

• Hematologic malignant diseases have variable initial presentations and significant associated complications.

• Rapid evaluation and intervention are essential to minimize morbidity and mortality in the immunocompromised patient.

Epidemiology

The National Cancer Institute estimated that approximately 137,260 new cases and 54,020 deaths from hematologic malignant diseases (leukemias, lymphomas, and plasma cell disorders) occurred in 2010. On January 1, 2007, approximately 908,512 men and women living in the United States had a history of hematologic malignant disease. In adults, non-Hodgkin lymphomas and chronic lymphocytic leukemia are the most common of these diseases.1 Of a total of 26,446 childhood cancers (age 1 to 19 years) diagnosed in the United States from 2001 to 2003, leukemias were the most common (26.3%). The lymphoid leukemias were the type with the highest incidence. Lymphomas, comprising 14.6% of new childhood malignant diseases, were the third most common cancers.1,2 A history of malignant disease is a common feature in the emergency department (ED) patient population. In a retrospective review of 5640 patients in a community teaching hospital with an annual ED census of 31,000, cancer history was identified in 5% of patients. Ten percent of patients with oncology-related visits died during the admission, and 48% died within 1 year of the ED visit.3

Pathophysiology

White blood cells (WBCs), or leukocytes, are the primary cells responsible for the inflammatory and immune response. WBCs include granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils) and mononuclear cells (T and B lymphocytes, monocytes). These cells are all produced from a common stem cell in the bone marrow, and they differentiate through various cytokines including colony-stimulating factors and interleukins. Normal blood leukocyte counts are 4.34 to 10.8 × 109/L, with neutrophils representing 45% to 74% of cells, bands representing 0% to 4%, lymphocytes representing 16% to 45%, monocytes representing 4% to 10%, eosinophils representing 0% to 7%, and basophils representing 0% to 2%.4 WBC disorders are the result of cell overproduction, underproduction, or dysfunction (Box 203.1). The WBC count with differential lacks specificity and sensitivity but is the most frequent laboratory test ordered by emergency physicians.5

Box 203.1

Differential Diagnosis of White Blood Cell Disorders by Pathogenesis

Adapted from Lepin HD, Powell BL. White cell disorders. In: Halter JB, Ouslander J, Tinetti M, et al, editors. Hazzard’s geriatric medicine and gerontology. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

Leukopenia

Leukopenia, or a WBC count less than 1.5 × 109/L, is most clinically relevant with significant neutropenia and its complications (primarily increased risk of infection, further outlined in Chapter 201). Although neutropenia is most common in patients with bone marrow suppression secondary to chemotherapy, Box 203.2 outlines a differential diagnosis of certain infections that characteristically manifest with neutropenia. Lymphocytopenia is a nonspecific finding that is present in many bacterial, fungal, viral, and protozoan infections.6

Leukocytosis

Leukocytosis, or an increased number of WBCs, is defined as an elevation in the total number of circulating WBCs greater than 2 standard deviations above the age-based mean circulating WBC count. This disorder is most commonly secondary to infections or systemic stressors; however, an increase in a subset of WBCs (neutrophilia, monocytosis, lymphocytosis, eosinophilia, or basophilia) may guide the differential diagnosis. Bacteria are the culprit in two thirds of infection-related cases of neutrophilia.7 Box 203.3 outlines infectious causes of lymphocytosis, with Bordetella pertussis being the rare bacterial exception. Eosinophilia is classically caused by multicellular parasites that invade tissue, most commonly seen in invasive parasitic disease, but it may also be seen in protozoan and fungal infections.8

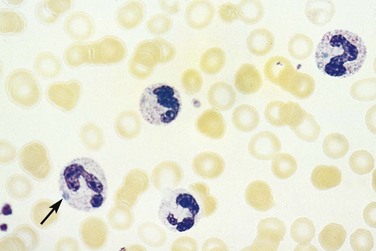

Morphologic Changes

In addition to altered numbers, changes in cellular morphology found in a peripheral blood smear may aid in the diagnosis. A left shift (or greater percentage of immature cells, such as metamyelocytes) may be present in severe infection. Intracellular abnormalities including toxic granulations, cytoplasmic vacuolization, and Dohle bodies are likely secondary to infection (Fig. 203.1).6

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Acute Myelogenous and Lymphoid Leukemias

Acute Myelogenous Leukemia

Patients with leukemia present with signs and symptoms secondary to the invasion of other organs by leukemic cells and decreased production of normal hematopoietic cells. Fever, malaise, and a viral-like syndrome are common presenting symptoms. Diffuse bony tenderness, as a result of expansion of the intramedullary space or periosteal infiltration by leukemic cells, is the initial symptom in 25% of patients.9

Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) typically affects all three cells lines and results in anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia. Pallor, dyspnea, and chest pain reflect anemia, whereas petechiae, ecchymosis, and excessive bleeding are a result of thrombocytopenia. One third of patients will have significant infections on diagnosis.10 Splenomegaly occurs in up to 50% of patients, and lymphadenopathy is rare.9

AML has several skin manifestations. Raised, nontender plaques or nodules (leukemia cutis) are manifest in many forms of leukemia, but they are most commonly seen in AML (Fig. 203.2).11 Tender, pseudovesicular, erythematous plaques are a characteristic feature of Sweet syndrome, which may precede the diagnosis of AML by months (Fig. 203.3). Gingival hyperplasia may also be present (Fig. 203.4).

Fig. 203.2 Leukemia cutis in a patient with monoblastic leukemia.

(From Miller KB, Pihan G. Acute myeloid leukemia. In: Hoffman R, Benz Jr EJ, Shattil SJ, et al, editors. Hematology: basic principles and practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2009.)

Fig. 203.3 Sweet syndrome in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia.

Tender, pseudovesicular, erythematous plaques are a characteristic feature of this syndrome.

(From Cohen PR. Acral erythema: a clinical review. Cutis 1993;51:175, with permission.)

Fig. 203.4 Generalized gingival hyperplasia in a patient with leukemia.

(Courtesy of Dr. Edward V. Zegarelli. In: Ibsen OAC, Phelan JA, editors. Oral pathology for the dental hygienist. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2004.)

Central or peripheral nervous system signs and symptoms on initial presentation are rare, although cranial nerve palsies (most commonly fifth and seventh) or meningeal signs have been documented.10

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia has a wide spectrum of presentations, but most commonly patients are diagnosed after an incidental finding such as enlarged lymph nodes (present in two thirds of patients at diagnosis), a palpable spleen (found in 40% of presenting patients), hepatomegaly (present in 10% of patients with a new diagnosis), or abnormal blood test results. Fatigue, lethargy, decreased appetite, weight loss, and decreased exercise tolerance are nonspecific, but they are again indicative of the effects of compromised hematopoiesis of all three cell lines. Central nervous system infiltration is rare; symptoms are more likely secondary to opportunistic infections.12

Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia

Thirty percent to 50% of patients diagnosed with chronic myelogenous leukemia are asymptomatic. Splenomegaly is present in 50% to 60%, and hepatomegaly occurs in 10% to 20% of new cases. Lymphadenopathy is rare.13

Hodgkin Lymphoma

Fever, night sweats, and weight loss are the classic “B” symptoms associated with Hodgkin lymphoma. Other classic signs are systemic pruritus and painful lymphadenopathy after drinking alcohol. Painless, rubbery, supradiaphragmatic lymphadenopathy, particularly of the neck and supraclavicular nodes, is common. Less than 10% of patients will have a subdiaphragmatic presentation.14

Plasma Cell Disorders

Fatigue and bone pain are the most common presenting symptoms of multiple myeloma.15 Pain may be secondary to characteristic lytic lesions or pathologic fractures (Fig. 203.5). Focal weakness or paresthesias may be secondary to nerve root or spinal cord compression from extramedullary expansion of bony lesions.

Differential Diagnosis, Medical Decision Making, and Treatment

Once the diagnosis of a hematologic malignant disease is suspected, laboratory evaluation should be performed, including a complete blood cell count with manual differential, peripheral blood smear, chemistry studies (including uric acid, creatinine, potassium, phosphorus, and calcium), coagulation factors, and blood type and screen. If the patient is febrile, blood cultures (aerobic, anaerobic, and fungal) should also be obtained, and empiric antibiotics should be initiated early because many of these patients have functional neutropenia, even in the setting of normal neutrophil count, and are at high risk of bacteremia or sepsis.16 Diagnostic imaging should be ordered based on the focality of patients’ symptoms, but a chest radiograph is a general starting point to evaluate any of the intrathoracic complications associated with these malignant diseases. An electrocardiogram should be performed to evaluate for evidence of electrolyte abnormalities.

Patients presenting with hyperleukocytosis (an extreme elevation of the blast count or WBC count >100,000/mm3) and many different symptoms affecting multiple organ systems are at an increased risk of hyperviscosity syndrome (see Box 203.5), a medical emergency with mortality rates as high as 40%.17 Metabolic and electrolyte abnormalities are common. The most serious complication is tumor lysis syndrome, a result of the massive cell lysis, which releases intracellular urate, phosphate, and potassium (please refer to Chapter 201 for details on tumor lysis syndrome).

Cardinal Presentations and Complications of Patients with Known White Blood Cell Cancer

Abdominal pain, dyspnea, fever, and malaise are all key chief complaints that require a comprehensive ED evaluation in patients with WBC disorders. Box 203.4 lists the differential diagnosis of these complaints.

Box 203.4 Differential Diagnosis of White Blood Cell Disorders by Signs and Symptoms

Abdominal Pain

Dyspnea

Malaise and Body Pains

• Elevated uric acid levels or gouty arthritis

• Osteopenic fractures (corticosteroid induced)

• Amyloidosis pains (accumulation of monoclonal plasma cells in tissues and organs, frequently the heart)12

ALL, Acute lymphocytic leukemia; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Abdominal Pain

Gastrointestinal symptoms are the most common chief complaints of patients with cancer who present to the ED.3 Immunosuppressed patients represent a diagnostic challenge, because classic examination findings of an acute abdomen may be replaced by nonspecific signs or systems such as tachycardia, hypotension, and altered mental status.18

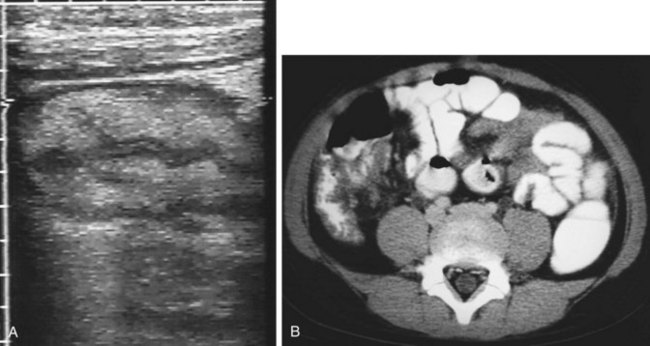

In addition to disorders present in the immunocompetent host, disorders secondary either to the malignant disease or to the therapy used to combat it should be considered. Opportunistic infections, intestinal obstruction, perforation, typhlitis, and venoocclusive disease of the liver (Budd-Chiari syndrome) should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient with cancer who has an acute abdomen. In a retrospective series of patients with acute leukemia who developed severe abdominal infections during chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, 68% presented with enterocolitis (primarily bacteremia, but also fungal and viral infections).19 A broad diagnostic strategy, including abdominal diagnostic imaging (computed tomography [CT] or ultrasound, or both), is usually necessary in the thorough evaluation of these patients.

Typhlitis, or neutropenic enterocolitis, is a necrotizing inflammation of the ascending colon or cecum that is a common cause of the acute abdomen in a neutropenic patient (Fig. 203.6).18 Although the incidence varies (from 0.8% to 26%), typhilitis has a mortality rate of 50% and higher.20 The pathogenesis is unclear, but theories have implicated failed mucosal integrity secondary to chemotherapy or the migration of bacteria causing bowel necrosis and hemorrhage secondary to the effects of neutropenia.21 Several case reports have described typhlitis as a presentation of acute leukemia.22,23 Signs and symptoms vary. In a retrospective case review of 10 patients, all presented with fever, and some had abdominal pain (most commonly right lower quadrant), nausea, diarrhea, and hypotension.24 CT imaging shows bowel wall thickening and cecal distention. Ultrasound imaging may show bowel wall thickening but is not specific. Therefore, CT is recommended in addition to ultrasound, to assess potential complications, including colonic wall hemorrhage, pneumatosis intestinalis, pneumoperitoneum, and abscesses, more thoroughly.25 Broad-spectrum antibiotics (covering enteric gram-negative organisms, Pseudomonas, and anaerobes including Clostridium difficile), bowel rest, surgical evaluation, and supportive care are recommended.

Fig. 203.6 Typhlitis.

(From Adam A, Dixon AK, editors. Grainger and Allison’s diagnostic radiology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2007.)

Hepatic venous outflow obstruction caused by thromboses, or Budd-Chiari syndrome, results from a hypercoagulable state or direct tumor invasion of the hepatic venous system. Venous stasis and hepatic congestion lead to cell death and eventual liver failure.26 Symptoms include ascites, hepatomegaly, abdominal pain, jaundice, and, in severe cases, variceal bleeding and portal hypertension. Ultrasound scanning with Doppler is the initial imaging modality of choice; it has a sensitivity of more than 85%, but CT and magnetic resonance imaging are alternatives.27 The initial management strategy consists of sodium restriction, diuretics, anticoagulation, and periodic paracentesis. Portosystemic shunting or liver transplantation is indicated for severe forms of Budd-Chiari syndrome.26

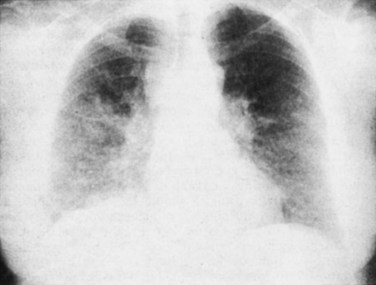

Dyspnea

Acute respiratory failure is the most common cause of admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) in patients with cancer, and it has an incidence of 10% to 50% and an overall mortality rate of 50%.28 Patients with leukemia and lymphoma have a higher incidence of respiratory insufficiency as the cause of ICU admission than do patients with solid tumors.28

Common causes of acute respiratory failure in these patients include pulmonary infections (pneumonia), cardiogenic or noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, antineoplastic (chemotherapy or radiation) therapy-induced lung injury, venous thromboembolism, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH), airway obstruction, and underlying disease progression.29

Pneumonia is the most common cause of respiratory failure in patients with hematologic malignant diseases. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae are the most common organisms in patients with leukemia and myeloma (impaired B-cell immunity). Patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (impaired T-cell immunity) are more likely to be infected with Pneumocystis jiroveci, mycobacteria and fungi, and viruses (including cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus). Presentation may be atypical. Although fever is common, cough and sputum are not, and findings on chest radiography may be normal. Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia can give rise to infection with Staphylococcus aureus, gram-negative bacilli (Pseudomonas and Klebsiella), and opportunistic fungi (Aspergillus).30 Debilitation, malnourishment, prolonged bed rest, and central nervous system metastasis predispose oncologic patients to increased aspiration risk.31

Chemotherapy- and radiation-induced lung injury comprises another syndrome that may manifest with exertional dyspnea, low-grade fevers, and a nonproductive cough during or up to several months after treatment. The various diagnoses include interstitial pneumonitis, acute lung injury, ARDS, capillary leak syndrome, organizing pneumonia, hypersensitivity reaction, bronchospasm, and DAH.30 On examination, bilateral inspiratory crackles may be auscultated, and diffuse or patch ground-glass opacities are seen on chest radiography and CT. Each syndrome requires a multipronged approach, but cessation of the culprit chemotherapeutic agent and treatment with systemic corticosteroids are general management principles.

Venous thromboembolism (deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism) is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with cancer and may be a predictor of worse overall prognosis.32 Chemotherapeutic agents, intrinsic procoagulant tumor activity, indwelling catheters, immobilization, and surgery are risk factors for venous thromboembolism in oncologic patients. Ten percent of patients with lymphoma develop venous thromboembolism.33 Presenting symptoms of dyspnea, pleurisy, and palpitations and signs of tachypnea, hypoxia, and dysrhythmias should prompt a thorough evaluation for venous thromboembolism.

DAH is common in patients with leukemia or multiple myeloma, after bone marrow transplantation, and in patients with thrombocytopenia (platelets < 50,000/mm3). Total body irradiation, thoracic irradiation, and increased age are all risk factors for DAH.30 Patients present with progressive dyspnea, cough, and fever but rarely hemoptysis. Chest radiography may show diffuse interstitial and alveolar infiltrates, and the diagnosis is confirmed by bronchoscopy. Supportive therapy includes corticosteroids, platelet transfusions, and mechanical ventilator support.

Transfusion-related acute lung injury may develop in those patients receiving red blood cells, platelets, or fresh frozen plasma. Patients develop fever, hypotension, hypoxemia, pulmonary hypertension, and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema within 6 hours of transfusion.34 Treatment is supportive and often requires ventilatory support.

Pain

The most common complaint of patients with cancer who present to the ED is pain, with nausea or vomiting and weakness a close second and third most frequent chief complaints.3 Although pain is nonspecific, the ED physician needs to be aware of critical, life-threatening diagnoses that may manifest with pain.

Hypercalcemia may occur in up to 30% of patients with cancer, and they may present with vague symptoms of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or myalgias.35 Hypercalcemia may lead to progressive neurologic symptoms, coma, renal failure, and arrhythmias. In multiple myeloma, hypercalcemia results from bone osteoclastic bone resorption. Lymphomas and myelomas hydroxylate vitamin D into 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1.25(OH)2D), the active form of vitamin D, thus enhancing intestinal absorption of vitamin D and resulting in hypercalcemia.35 This diagnosis is critical in this patient population because approximately 50% of these patients will die within 30 days.36 The diagnosis is best made by using ionized calcium, and an electrocardiogram may show a shortened QT interval. The cornerstone of management is aggressive intravenous and oral hydration. Once volume repletion is achieved, loop diuretics are used for calcium excretion. Bisphosphonates, calcitonin, and steroids are other adjuncts, depending on the response to treatment and the primary cause of the elevated calcium concentration. Please refer to Chapter 201 for further details on hypercalcemia.

Acute blood hyperviscosity results from elevations of serum proteins (hyperviscosity syndrome) or WBCs (hyperleukocytosis) in the blood circulation. Leukocytosis and leukostasis (Fig. 203.7) have mortality rates that range from 20% to 40%, and these conditions therefore represent an emergency diagnosis.17 Boxes 203.5 and 203.6 outline the presentations and management of both conditions.

Box 203.5

Hyperviscosity Syndrome Presentation and Management

Adapted from Adams BD, Baker R, Lopez JA, Spencer S. Myeloproliferative disorders and hyperviscosity syndrome. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2009;27:459–76.

Box 203.6

Hyperleukocytosis Syndrome Presentation and Management

Adapted from Adams BD, Baker R, Lopez JA, Spencer S. Myeloproliferative disorders and hyperviscosity syndrome. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2009;27:459–76.

Matasar MJ, Zelenetz AD. Overview of lymphoma diagnosis and management. Radiol Clin North Am. 2008;46:175–198.

Mattu A. Cancer emergencies. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2009;27:174–354.

Menon KV, Shah V, Kamath PS. The Budd-Chiari syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:578–585.

Nau KM, Lewis WD. Multiple myeloma: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78:853–859.

Swenson KK, Rose MA, Ritz L, et al. Recognition and evaluation of oncology-related symptoms in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;26:12–17.

1 National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program. http://www.seer.cancer.gov/.

2 Li J, Thompson TD, Miller JW, et al. Cancer incidence among children and adolescents in the United States, 2001-2003. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1470–e1477.

3 Swenson KK, Rose MA, Ritz L, et al. Recognition and evaluation of oncology-related symptoms in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;26:12–17.

4 Holland SM, Gallin JI. Disorders of granulocytes and monocytes. Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, et al. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 18th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012. http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=9113657. Accessed April 27, 2012.

5 Young G. CBC or not CBC? That is the question. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15:367–371.

6 Marks P, Rosenthal D. Hematologic manifestations of systemic disease: infection, chronic inflammation, and cancer. Hoffman R, Benz Jr, EJ., Shattil SJ, et al. Hematology: basic principles and practice, 5th ed, Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2009.

7 Emerson W, Ieve P, Krevens J. Hematological changes in septicemia. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1970;126:69–76.

8 Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilia. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1592–1600.

9 Miller K, Pihan G. Clinical manifestations of acute myeloid leukemia. Hoffman R, Benz Jr, EJ., Shattil SJ, et al. Hematology: basic principles and practice, 5th ed, Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2009.

10 Appelbaum F. Acute myeloid leukemia in adults. Abeloff M, Armitage J, Niederhuber J, et al. Abeloff’s clinical oncology, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2004.

11 Seckin D, Senol A, Gurbuz O, Demirkesen C. Leukemic vasculitis: an unusual manifestation of leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:519–521.

12 Kantarjian H, O’Brien S. The chronic leukemias. Goldman L, Ausiello DA, Arend W, et al. Cecil medicine, 23rd ed, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2007.

13 Kantarjian H, Cortes J. Chronic myeloid leukemia. Abeloff M, Armitage J, Niederhuber J, et al. Abeloff’s clinical oncology, 4th ed, Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2008.

14 Horning S. Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Abeloff M, Armitage J, Niederhuber J, et al. Abeloff’s clinical oncology, 4th ed, Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2008.

15 Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:21–33.

16 Nazemi KJ, Malempati S. Emergency department presentation of childhood cancer. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2009;27:477–495.

17 Porcu P, Farag S, Marcucci G, et al. Leukocytoreduction for acute leukemia. Ther Apher. 2002;6:15–23.

18 Scott-Conner CE, Fabrega AJ. Gastrointestinal problems in the immunocompromised host: a review for surgeons. Surg Endosc. 1996;10:959–964.

19 Gorschlüter M, Glasmacher A, Hahn C, et al. Severe abdominal infections in neutropenic patients. Cancer Invest. 2001;19:669–677.

20 Gorschlüter M, Mey U, Strehl J, et al. Neutropenic enterocolitis in adults: systematic analysis of evidence quality. Eur J Haematol. 2005;75:1–13.

21 Katz JA, Wagner ML, Gresik MV, et al. Typhlitis: an 18-year experience and postmortem review. Cancer. 1990;65:1041–1047.

22 Kaste SC, Flynn PM, Furman WL. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia presenting with typhlitis. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28:209–212.

23 Sloas MM, Flynn PM, Kaste SC, Patrick CC. Typhlitis in children with cancer: a 30-year experience. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:484–490.

24 Hsu TF, Huang HH, Yen DH, et al. ED presentation of neutropenic enterocolitis in adult patients with acute leukemia. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22:276–279.

25 Gorschlüter M, Marklein G, Höfling K, et al. Abdominal infections in patients with acute leukaemia: a prospective study applying ultrasonography and microbiology. Br J Haematol. 2002;117:351–358.

26 Menon KV, Shah V, Kamath PS. The Budd-Chiari syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:578–585.

27 Bolondi L, Gaiani S, Li Bassi S, et al. Diagnosis of Budd-Chiari syndrome by pulsed Doppler ultrasound. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1324–1331.

28 Staudinger T, Stoiser B, Müllner M, et al. Outcome and prognostic factors in critically ill cancer patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:1322–1328.

29 Azoulay E, Mokart D, Lambert J, et al. Diagnostic strategy for hematology and oncology patients with acute respiratory failure: randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1038–1046.

30 Pastores SM, Voigt LP. Acute respiratory failure in the patient with cancer: diagnostic and management strategies. Crit Care Clin. 2010;26:21–40.

31 Pastores SM. Acute respiratory failure in critically ill patients with cancer: diagnosis and management. Crit Care Clin. 2001;17:623–646.

32 Piccioli A, Prandoni P. Approach to venous thromboembolism in the cancer patient. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2011;13:159–168.

33 Lee AY, Levine MN. Venous thromboembolism and cancer: risks and outcomes. Circulation. 2003;107(suppl I):I17–I21.

34 Cherry T, Steciuk M, Reddy VV, Marques MB. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: past, present, and future. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:287–297.

35 Stewart AF. Clinical practice: hypercalcemia associated with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:373–379.

36 Ralston SH, Gallacher SJ, Patel U, et al. Cancer-associated hypercalcemia: morbidity and mortality. Clinical experience in 126 treated patients. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:499–504.