chapter 47 Weight problems and eating disorders

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

BACKGROUND

Anorexia nervosa was first described by Sir William Withey Gull in 1873, although he mistakenly assumed that the emaciated woman he discussed had no appetite. Binge eating among anorexia nervosa patients was described in 1979 and the first diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa was proposed in 1979. The prevalence of eating disorders is not increasing but the awareness of these problems by lay people and healthcare professionals has risen exponentially in the past 40 years. The presentation of patients can be slightly different in different cultures and appears to be changing. The emphasis on body image, with adolescent women wanting to be like skinny models and film stars, is declining. Currently the governments and public health professionals in most developed countries are attempting to educate people to try to combat the increasing incidence of obesity in all age groups of people. As a result, more adolescents presenting with eating disorders are aiming to ‘eat healthily and exercise more’, in contrast to ‘lose weight for a perfect body image’.

PREVALENCE

Current information suggests that the figures in Box 47.1 give a reasonable estimate of the prevalence of the eating disorders in women aged 13–30 years. Not all these people have sought treatment for their eating disorder and the majority are not assessed and treated by eating disorder specialists.

BOX 47.1 Prevalence of eating disorders by age 30

Anorexia nervosa: 1% (range 0.5–2%)

Bulimia nervosa: 2% (range 1–3%)

(EDNOS: eating disorder not otherwise specified; includes binge-eating disorder.)

The estimated prevalence of anorexia-nervosa-like problems is probably 3–4% and bulimia-nervosa-like 6–8%. These women are included in the EDNOS prevalence in Box 47.1. The prevalence of binge-eating disorder is thought to be 1–4%, with one in three being male, but this may not include older men and women, and may include adolescent sufferers of any or all of the other eating disorders.

AETIOLOGY

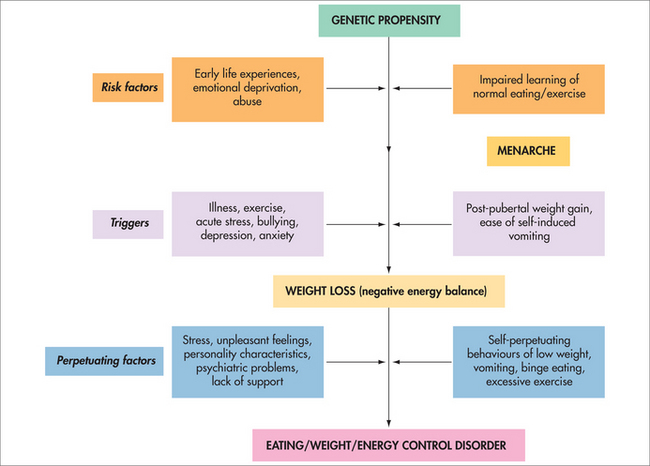

There is no consensus on why eating disorders occur. There are many explanations and these include genetic, physiological, social and psychological perspectives (Fig 47.1) and involve theories relating to childhood and adolescent development. Weight loss precedes the onset of the eating disorder. The initial weight loss may be intentional and in response to post-pubertal weight gain in women, or it may occur for other reasons such as illness or change in exercise routine.

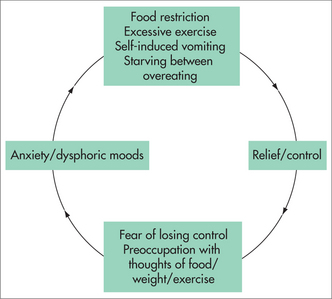

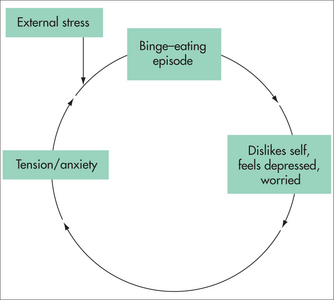

PERPETUATING FACTORS

Factors associated with the beginnings of the eating disorder may not be those that cause it to continue for more than a brief period and possibly to become chronic (Fig 47.2). Simple examples are receiving attention from people, achieving what others cannot, being able to eat anything and not put on weight, or being a scapegoat for family problems.

All the behaviours are associated with temporary decreases in anxiety and dysphoric moods.

ASSESSMENT

It is helpful to see the family or partner.

The risk factors, trigger factor and perpetuating factors involved in the development and maintenance of the eating disorders (Fig 47.3) give a guide to the history. Family medical and psychiatric histories are necessary.

PSYCHOLOGICAL AND PHYSICAL SYMPTOMS

The psychological changes that may accompany low weight are seen in people during starvation (Box 47.2). These same symptoms are seen in women who are not underweight, because they are having episodes of overeating or binge-eating between their periods of severe weight-losing behaviour. Insomnia is thought to be secondary to the hyperactivity, which in turn can be viewed as ‘food-seeking behaviour’. The depressed mood is usually described as feelings of hopelessness, guilt and worthlessness. Some cite anger if their binge eating is disturbed. All are anxious around food.

The physical symptoms (Boxes 47.3 and 47.4) associated with eating disorders result from starvation, the extreme methods of weight control employed and excessive binge eating, and hence include the symptoms of low body weight, high body weight, dehydration and electrolyte disturbance.

GASTROINTESTINAL DISTURBANCE

At low weight there is a reduction in time for gastric emptying and transit in general. Constipation and irritable bowel type symptoms are common. Pain, discomfort and bloating occur when eating is attempted. There may be some sensitivity to fructose and sorbitol at low weight. Bloating is a common symptom following eating if the person is eating infrequently. Most functional gastrointestinal diseases associated with the eating disorders—including functional heartburn and gastro-oesophageal reflux, which are more likely if the patient is binge eating and vomiting, and IBS—improve as recovery progresses.

TREATMENT

NUTRITIONAL REHABILITATION

Nutritional rehabilitation consists of learning ‘normal structured eating’. A dietician can provide a menu plan (guide) that fulfils the criteria for ‘normal eating’ (see Box 47.5). This is not a ‘diet’ and there are no such things as ‘bad’ foods or ‘healthy’ foods in a normal eating plan.

BOX 47.5 ‘Normal structured eating’

SUPPLEMENTATION

A suggested regimen might include:

Adjunctive nutritional rehabilitation may include reducing caffeine, tobacco and alcohol intake, as well as addressing deficiencies with supplementation.

PSYCHOLOGICAL AND LIFE SKILLS MANAGEMENT

MEDICATIONS

Antidepressants

A possible explanation for the ineffectiveness of SSRIs in underweight anorexia nervosa patients is that they may have reduced synaptic 5-HT. 5-HT is derived from tryptophan, and plasma levels are significantly reduced with weight loss and malnourishment in anorexia nervosa.1 This in turn reduces brain 5-HT synthesis and therefore impairs serotonin activity. A previous study showed that depletion of tryptophan will reverse the effects of antidepressants in depressed patients.2

TREATMENT BY WHOM AND WHERE?

PREVENTION

Janet Treasure, A guide to the medical risk assessment for eating disorders, Section of Eating Disorders, Institute of Psychiatry, South London and Maudsley NHS trust. http://www.iop.kcl.ac.uk/sites/edu/downloads/HP/STUDENT_COUNSELLOR_GUIDE_TO_EATING_DISORDERS.pdf.

Suzanne Abraham, Eating disorders: the facts. 6th edn. Oxford: OUP; 2008.