chapter 41 Respiratory medicine

IMPORTANT CONDITIONS

The four diagnoses that are most prominent and/or important in general practice are:

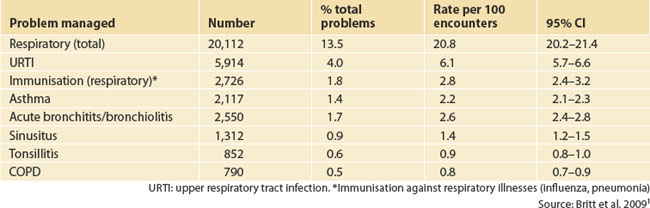

The Bettering the Evaluation And Care of Health (BEACH) data show the distribution of respiratory problems managed in general practice (Table 41.1).1

ASTHMA

BACKGROUND AND PREVALENCE

It is estimated that worldwide as many as 300 million people of all ages have currently diagnosed asthma. The prevalence of asthma in Australia is quite high, with one in six children (14–16%) and one in nine adults (10–12%) having the disease.2 There is variation between countries in the incidence of asthma (this is detailed in the document Global burden of asthma (see Resources list at the end of this chapter)).

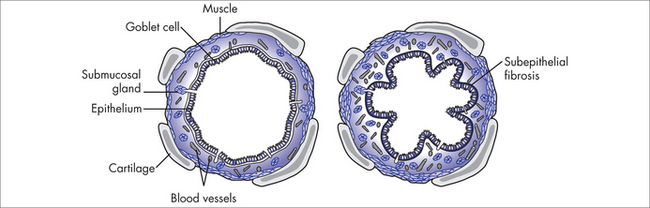

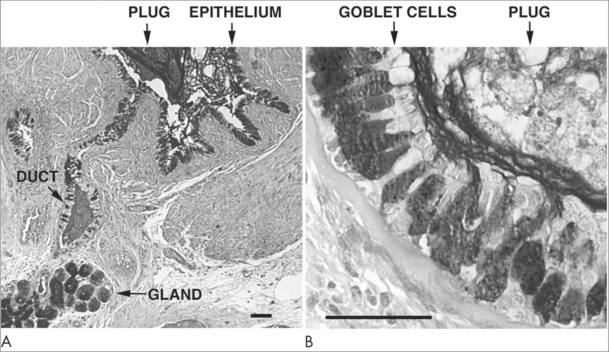

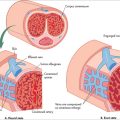

The condition we call asthma involves a number of pathological processes including inflammation, smooth muscle spasm and increased airways secretions. In essence it is a chronic inflammatory disorder affecting the airways. Many types of cells play a role in this inflammatory process, including mast cells, eosinophils, T-lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils and epithelial cells. Individuals who experience asthma generally have a genetic susceptibility that can also be affected by lifestyle and environmental factors. Airway inflammation causes recurrent episodes of asthma associated with the symptoms of wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and also coughing, most commonly at night or in the early morning or in response to exercise. These episodes of wheezing and dyspnoea brought on by widespread airflow obstruction will reverse spontaneously or with treatment.2 In those disposed to airway hypersensitivity, the inflammation is usually triggered by environmental factors such as allergens, irritants and temperature change. Psychological and emotional factors can also trigger or aggravate episodes of asthma.

AETIOLOGY

Asthma manifests as a combination of atopy, bronchial hyper-reactivity and IgE- and non-IgE-mediated acute and chronic immune responses. Most authorities accept that it occurs as a result of the action of a variety of environmental stimuli on genetically predisposed people.3

HISTORY

EXAMINATION

Physical examination is, on most occasions, normal unless the patient is in the midst of an asthma attack (i.e. an episode of bronchospasm). In the past, the chronic untreated asthma sufferer sometimes had a deformed thoracic area with a barrel chest and spreading of the ribs, but this is now only seen, in developed countries, in historical textbooks of medicine.

INVESTIGATIONS

INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT

Prevention

The ‘hygiene hypothesis’4 is a theory, still being debated,5 that links an increased risk of atopic disease with reduced microbial exposure from a variety of sources during childhood. Epidemiological studies are providing increasingly strong evidence that protection from atopic disorders including asthma is afforded by early-life exposure to environmental microbes. For example, children who are raised on farms, who drink unpasteurised milk, have more older siblings or attend day care at an earlier age are protected to some extent against asthma. This may explain to some extent the ‘asthma epidemic that has been occurring, especially in developed nations, over the past several decades’.6

Active surveillance

If we look back to when there were no effective treatments for asthma, the consequences of providing no active intervention are well described. Although patients can sometimes learn to ride out mild asthma attacks using self-help techniques such as breathing exercises, thereby reducing the need for reliever medication, doing nothing for moderate to severe asthma, or not taking preventer medications where asthma episodes are frequent, would not be considered a valid option. A worst-case scenario is that it is life-threatening. This is especially so for those with a history of brittle asthma and severe attacks.

Self-help

House dust mite control

The major allergen in house dust comes from mites. Although methods of reducing dust mite exposure, such as adequate ventilation, keeping a dust-free environment and having regular fresh bed linen, are intended to reduce asthma symptoms, these methods have not been as successful as expected.7

Ion generator

Although marketed for use in homes to reduce asthma by removing dust and smoke particles, and although some studies show that ion generators can alter airways function, ‘the few studies which have been conducted in the homes of people with asthma, demonstrate no significant benefit in improving lung function or symptoms’.8

Pets

Some people with asthma are allergic to their own and others’ pets. The solution for many is the removal of the pets, to reduce exposure to the allergens in their hair and skin, but other methods such as pet washing, sprays and air filtration units can help reduce the amount of allergen in the air and on the floor of the home. The evidence is not at present conclusive.9

Caffeine

Caffeine (a methylxanthine drug) is related to the theophyllines that used to be commonly prescribed for asthma. These have an effect on the airway musculature. Caffeine is commonly found in coffee, tea, cola drinks and cocoa, and it has been found that even small amounts of caffeine can improve lung function for up to 4 hours, but for some the amount required to improve symptoms may be offset by the other side effects of caffeine.10

Fish oil

Many people with asthma who change their diets to include more fish oil do not improve their asthma,11 but other evidence has suggested that others do. There has been some work published on taking fish oil supplements (rather than just increasing fish in the diet). In one study,12 some benefit was shown in people with predominately exercise-induced bronchospasm (EIB) but the authors have given the guarded advice that ‘fish oil supplementation may represent a potentially beneficial non-pharmacological intervention in asthmatic patients with EIB’.

Vitamin C, vitamin E and beta-carotenes

Longitudinal data support the hypothesis that fresh fruit consumption has a beneficial effect on the lung. Among children, consumption of fresh fruit, particularly fruit high in Vitamin C, has been related to a lower prevalence of asthma symptoms and higher lung function.13

The message is therefore that a healthy diet is far more likely to be beneficial in asthma than supplements, particularly in the presence of a poor diet.13

Pharmacological

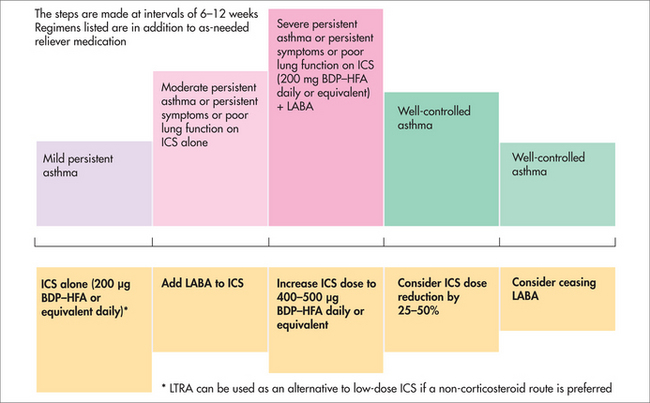

The cornerstone of asthma management is the use of inhaled corticosteroids. The greatest challenge is in deciding when they are required and in what dose. The recommendation of the National Asthma Council Australia is summarised in Figure 41.3.2a

Breathing exercises

The way in which ‘breathing exercise’ or ‘re-training’ is understood varies depending on the form of the therapy, the therapist providing the therapy and the cultural background of the person having the therapy. Some of the earlier studies of breathing exercises were small or had methodological flaws, but more recent studies demonstrate a trend for improvement.15 Evidence on breathing exercises, including yoga-based breathing exercises16, in asthma suggests that they can provide objective and subjective benefit and can be useful in reducing the need for reliever and preventer use.17 The Buteyko method is also widely used in asthma. Evidence suggests that it provides subjective benefit, although results indicating whether it also provides objective benefit have been inconsistent. It is best to learn breathing exercises from health professionals trained in their use.

Complementary therapies

Dietary supplements

There has been much interest in whether specific dietary supplementation can influence the clinical course of asthma. Many entities and results have been examined but the authors of the studies are careful in making claims. One study showed that the lipid extract of New Zealand green-lipped mussel had a beneficial effect in patients with atopic asthma.18

Adolescents with a less nutritious diet, with a lower intake of antioxidants and anti-inflammatory micronutrients, have poorer pulmonary function and increased respiratory symptoms, especially among smokers. The likely explanation is that these nutrients promote respiratory health and lessen the effects of oxidative stress.19 Dietary supplementation or adequate intake of lycopene and foods rich in vitamin A may also be beneficial in asthma.20

Acupuncture

The evidence is not clear and consistent enough to make firm recommendations about the value of acupuncture in asthma.21 It may be that some forms of acupuncture are more beneficial than others, or that acupuncture is beneficial for some variants of asthma but not others.

Alexander Technique

The Alexander Technique is a form of movement-based physical therapy. It is commonly used to correct posture and bring the body into natural alignment, and also as an aid to relaxation and greater body awareness. Although there are some positive findings, a review of trials found that there was not enough evidence to show a benefit of the Alexander Technique in reducing the need to use medication for asthma.22

Herbal treatments

Evidence from 27 trials covering 21 different herbal treatments for both adults and children, and from both inpatient and outpatient settings, was inconclusive generally because of methodological limitations of the trials. Although further trials of high quality are needed to assess the use of herbal treatments in asthma, there is enough positive preliminary evidence to suggest that some of these compounds will prove to be of benefit.23

Homeopathy

Different types of homeopathy are used for asthma, such as classical homeopathy (tailored to an individual’s bodily and psychological constitution and their symptoms) or isopathy (e.g. using a dilution of an agent that causes an allergy, such as pollen). In the existing studies on homeopathy and asthma, the type of homeopathy used varies and study designs are sometimes poor. Consequently, there is no strong evidence that homeopathy is effective for asthma.24

Speleotherapy

Speleotherapy, or staying in an underground environment such as a cave or mine, is believed by some to be of benefit for people with asthma. If benefits are there, it is believed that they come from air quality, underground climate (cool and humid), air pressure or radiation. Evidence is more anecdotal than derived from high-quality randomised controlled trials.25

CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE

BACKGROUND AND PREVALENCE

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of disability, hospital admission and premature death. It is commonly associated with other diseases including heart disease, lung cancer, stroke, pneumonia and depression.26 In a community-based survey that included lung function testing, doctor-diagnosed chronic bronchitis or emphysema was reported by 4.3% of the population. When clinical diagnosis is combined with complex lung function testing and an FEV1/FVC of less than 75%, around 12% of the population have some evidence of emphysema.27 This figure will be considerably higher in countries where anti-smoking legislation and campaigns are less prominent.

AETIOLOGY

COPD is the end result of chronic insults to the lungs. 70% of COPD is related to cigarette smoking28 but it can result from any particulate matter insult (in low-income countries this is often the indoor burning of biomass for cooking and heating) or air pollution.

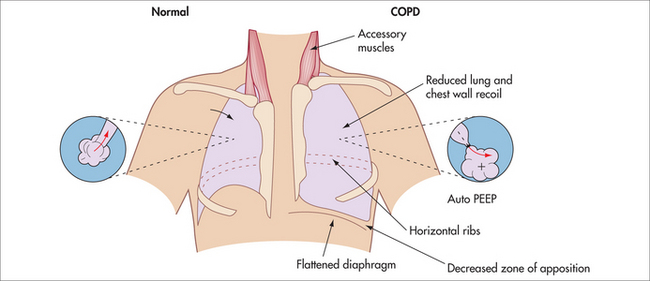

EXAMINATION

The physical examination gives an indication of the predominant pathology:

INTEGRATIVE MANAGEMENT

Of exacerbations, approximately 80% are infectious (40–50% bacterial, 30–40% viral and 5–10% atypical) and 20% are non-infectious (due to either an increase in the environmental load of irritants or non-compliance with management strategies including medications). The viral exacerbations correlate with viral epidemics among children. COPD sufferers who are still smoking get more viral infections than non-smokers and so get more exacerbations.

Self-help

As most smokers quit without any particular medical intervention, simply identifying and advising current cigarette smokers to quit is of benefit (see Ch 62, Substance misuse).

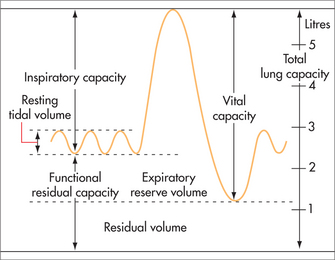

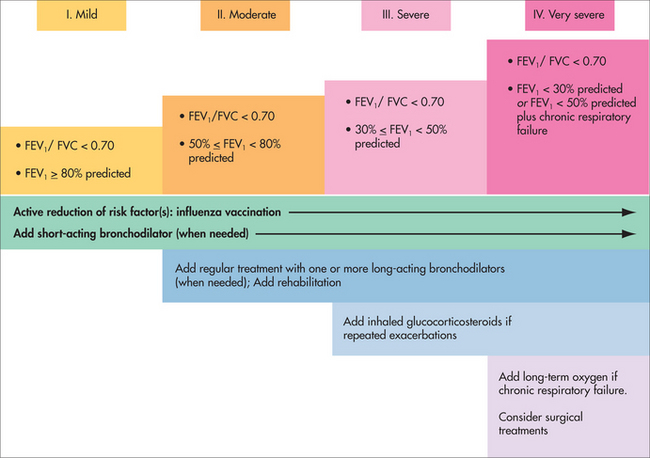

Pharmacological

The stages of COPD are defined using spirometry. The definition depends on having a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio ≤ 0.7. The severity of the COPD is graded on the degree of airflow obstruction compared with the population (in Fig 41.6 this is stated as ‘% predicted’). Therefore, mild COPD is a FEV1/FVC ratio ≤ 0.7 with FEV1 ≥ 80% predicted for a person of the same age, gender, height and ethnicity. Modern electronic spirometers calculate the ‘% predicted’ for the practitioner.

Surgical

Lung volume reduction surgery is a major operation sometimes offered to people with severe emphysema. The assessment of patients being considered for operation is complex and is usually reserved for specialised multidisciplinary units. There is significant perioperative mortality with this surgery. The outcomes of surgery suggest that, in patients who survive up to 3 months post surgery, there is significantly better health status and lung function in those who have the surgery than in those who have the usual medical care alone.29

Complementary therapies

Herbal medicines

The effectiveness of herbal medicines for treating COPD is not well established and so more high-quality trials are needed.30

Nutritional supplementation

Low body weight is common in people with COPD, which impairs heart and lung function enough to reduce the person’s ability to exercise as an aid to recovery. A degree of malnutrition is common in people with COPD and can signify a lack of self-care or other comorbidity, but it is unclear whether this is the cause of their deterioration, or just a sign of disease progression. It is questionable whether nutritional supplementation makes a significant difference to the course of COPD itself, but it will nevertheless be useful for general wellbeing.31

ONGOING REVIEW AND/OR MONITORING

Unfortunately, COPD is a progressive disease. The rate of progression is affected by whether:

PROGNOSIS

COPD is a relentlessly progressive disease and the best that can be hoped for is to slow the rate of progression and minimise symptoms. It is possible to predict the longer-term progression of COPD by using the BODE index.32 The BODE parameters, measurable in general practice, are:

The prognosis of COPD depends on disease severity and, as earlier diagnosis and smoking cessation influence this, all healthcare providers should aim to assess and provide advice on smoking to the people they see in consultation.

LUNG CANCER

According to the World Health Organization, cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide: it accounted for 7.9 million deaths (around 13% of all deaths) in 2007. Most cancer deaths are caused by cancer of the lung, stomach, liver, colon and breast cancer. Tobacco use is the single most important risk factor for cancer.33

In a general practice caring for approximately 10,000 patients, there may be four new lung cancer diagnoses per year.34

Non-small-cell lung cancer represents approximately 80% of lung cancers.35 Non-small-cell lung cancers are broadly divided by their main cell type into squamous cell, adenocarcinoma and large cell. If detected early it can initially be managed with local treatments such as surgery and/or radiotherapy.

INVESTIGATIONS

INTEGRATIVE MANAGEMENT

Prevention

As cigarette smoking and working with dusts and chemicals are known to cause lung cancer, preventive strategies based on encouraging and supporting smoking cessation and mandating protective programs for those who are exposed to noxious dusts and chemicals are critical in preventing lung cancers.

Surveillance

Surveillance alone is not a valid option unless the malignancy is so far advanced that palliation is all that can be offered (see Ch 39, Palliative medicine).

PROGNOSIS

Small-cell lung cancer

Small-cell lung cancer is an aggressive disease. The median survival time for limited disease is 18–24 months, with only 25% of patients alive after 5 years. More extensive disease is treated with chemotherapy and, even with this treatment, median survival is in the order of 12 months, with only 10% of patients surviving for 2 years.36

Non-small-cell lung cancer

Of patients with operable non-small-cell lung cancers that have not metastasised, up to 80% can expect to be alive at 5 years. For tumours that have spread to the lymph nodes, the 5-year survival rate drops to 25–30%. For patients with more widespread metastatic spread but who are still fit enough to receive chemotherapy, the 5-year survival rate is in the order of 15–35%.37

INFECTIONS

Respiratory infections can be classified as viral, bacterial, atypical or tuberculosis.

VIRAL UPPER RESPIRATORY TRACT INFECTIONS

The prevalence of upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) is shown in Table 41.2.

Treatment

Most of the respiratory infections seen in primary care are self-limiting viral URTIs. Even though it is almost impossible for people to avoid coming into contact with these viruses, it is important to keep the defences in the best possible condition and so minimise the number of URTIs contracted. How to maintain the healthiest possible immune system is discussed elsewhere (see Ch 32, Principles of the immune system).

Complementary therapies

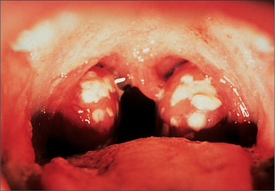

TUBERCULOSIS

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a global problem. In 2008, there were an estimated 9.4 million incident cases worldwide—this is equivalent to 139 cases per 100,000 population. Most of the estimated number of cases in 2008 occurred in Asia (55%) and Africa (30%).43

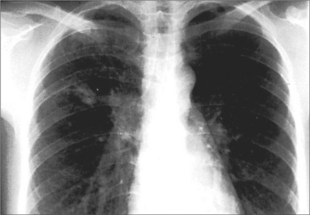

The symptoms of TB are vague (cough, sputum, breathlessness, haemoptysis, weight loss, fever, malaise and anorexia).44 Think of it in the person with a chronic cough, particularly if it is productive. There are also extra-pulmonary manifestations of TB, including lymph nodes, genitourinary tract, pleura, pericardium, bones and joints, meninges, eye, skin, adrenal glands and gut.

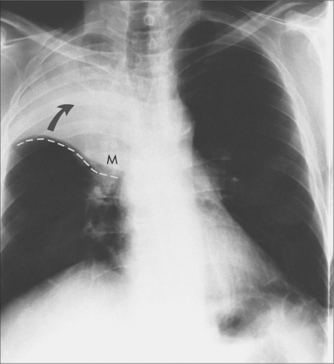

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made on the basis of the chest X-ray and sputum microscopy and culture.44 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) rapid diagnostic tests are available in some places but the more important thing is that the possibility of TB is considered and acted upon.

A Mantoux test may be a useful guide.

Biopsy of accessible extra-pulmonary lesions such as lymph nodes may be performed.

Treatment

According to Australian Therapeutic Guidelines: Respiratory,45 patients with TB should:

Adequate adherence to anti-tuberculous therapy is vital in order to:

Measures to improve adherence include:

The most common drugs used to treat TB are isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, ethambutol and streptomycin, usually in combinations of four. If problems with supply of anti-tuberculous drugs arise, the state health department should be contacted.

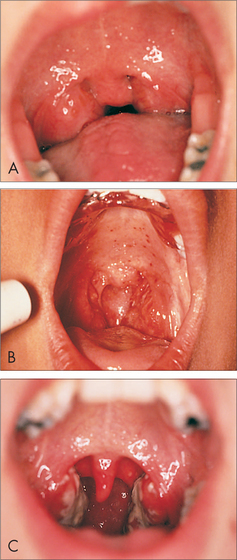

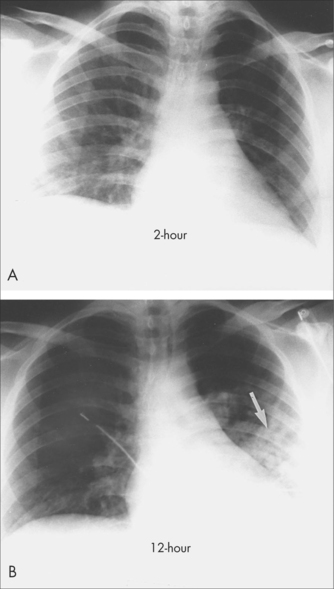

COMMUNITY-ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA AND THE ATYPICAL INFECTIONS

In community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), the patient is unwell, with high fever. It is more than a simple URTI. The disease is more common in the very young and the very old. The most common organism is Streptococcus pneumoniae but, in one study, in 22% of cases of CAP where an organism was identified, it was an atypical organism (Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae and Legionella spp).46

Diagnostic approach

Investigations

Integrated management

Prevention

Some children with specific medical problems require vaccination against invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) separately from the usual immunisation program. These conditions are listed in Box 41.1.

BOX 41.1 Underlying medical conditions predisposing children aged 9 years or younger to IPD47

Ongoing review and/or monitoring

These patients are often very unwell, and hospital admission will need to be considered. There are validated severity scales (e.g. CURB-65) that guide diagnosis, but how to proceed remains a clinical decision.46

Australian Lung Foundation. http://www.lungnet.com.au.

Cancer Council of Australia. http://www.cancer.org.au.

Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA), Global Burden of Asthma. http://www.ginasthma.com.

International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG). http://www.theipcrg.org.

National Asthma Council Australia. http://www.NationalAsthma.org.au.

1 Britt H, Miller GC, Charles J, et al. General practice activity in Australia 2008–09. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, December 2009. Cat. GEP 25; Table 7.2.

2 National Asthma Council Australia (NACA). Asthma management handbook 2006. Melbourne: NACA, 2006;3.

3 Holgate ST, Boushey HA, Fabbri LM, editors. Difficult asthma. London: Martin Dunitz; 1999:183.

4 Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ. 1989;299:1259-1260.

5 Goldberg S, Israeli E, Schwartz S, et al. Asthma prevalence, family size, and birth order. Chest. 2007;131(6):1747-1752.

6 Kline JN. Eat dirt. CpG DNA and immunomodulation of asthma. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:283-288.

7 Gøtzsche PC, Johansen HK. House dust mite control measures for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:CD001187.

8 Blackhall K, Appleton S, Cates CJ. Ionisers for chronic asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2:CD002986.

9 Kilburn S, Lasserson TJ, McKean M. Pet allergen control measures for allergic asthma in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD002989.

10 Welsh EJ, Bara AI, Barley EA, et al. Caffeine for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD001112.

11 Thien FCK, De Luca S, Woods R, et al. Dietary marine fatty acids (fish oil) for asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;2:CD001283.

12 Mickelborough TD, Lindley MR, Ionescu AA, et al. Protective effect of fish oil supplementation on exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in asthma. Chest. 2006;129:39-49.

13 Romieu I, Trenga C. Diet and obstructive lung diseases. (Review) Epidemiol Rev. 2001;23(2):268-287.

14 Ram FS, Ardern KD. Tartrazine exclusion for allergic asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;4:CD000460.

15 Holloway E, Ram FSF. Breathing exercises for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;1:CD001277.

16 Nagendra H, Nagarathna R. An integrated approach of yoga therapy for bronchial asthma: a 3–54 month prospective study. J Asthma. 1986;23(3):123-137.

17 Slader CA, Reddel HK, Spencer LM, et al. Double blind randomized controlled trial of two different breathing techniques in the management of asthma. Thorax. 2006;61:651-656.

18 Emelyanov A, Fedoseev G, Krasnoschekova O, et al. Treatment of asthma with lipid extract of New Zealand green-lipped mussel: a randomised clinical trial. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:596-600.

19 Burns JS, Dockery DW, Neas LM, et al. Low dietary nutrient intakes and respiratory health in adolescents. Chest. 2007;132(1):238-245.

20 Riccioni G, Bucciarelli T, Mancini B, et al. Plasma lycopene and antioxidant vitamins in asthma: the PLAVA study. J Asthma. 2007;44(6):429-432.

21 McCarney RW, Brinkhaus B, Lasserson TJ, et al. Acupuncture for chronic asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;3:CD000008.

22 Dennis J, Cates CJ. Alexander technique for chronic asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD000995.

23 Arnold E, Clark CE, Lasserson TJ, et al. Herbal interventions for chronic asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD005989.

24 McCarney RW, Linde K, Lasserson TJ. Homeopathy for chronic asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;1:CD000353.

25 Beamon S, Falkenbach A, Fainburg G, et al. Speleotherapy for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;2:CD001741.

26 McKenzie DK, Abramson M, Crockett AJ, et al. The COPD-X Plan: Australian and New Zealand guidelines for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 2009. Online. Available: http://www.copdx.org.au/guidelines/.

27 Abramson M, Raven J, Skoric B, et al. Prevalence of COPD amongst middle aged and older adults. Respirology. 2003;8(Suppl 2):A59.

28 Wilson D, Adams R, Appleton S, et al. Difficulties identifying and targeting COPD and population-attributable risk of smoking for COPD. A population study. Chest. 2005;128:2035-2042.

29 Tiong LU, Gibson PG, Hensley MJ, et al. Lung volume reduction surgery for diffuse emphysema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD001001.

30 Guo R, Pittler MH, Ernst E. Herbal medicines for the treatment of COPD: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:330-338.

31 Ferreira IM, Brooks D, Lacasse Y, et al. Nutritional supplementation for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD000998.

32 Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, et al. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1005-1012.

33 World Health Organization. Cancer. Online. Available: www.who.int/cancer/en/index.html, 2 April 2010.

34 McAvoy B, Elwood M, Staples M. Cancer in Australia. An update for GPs. Aust Family Physician. 2005;34(1/2):41-45.

35 Cancer Council Australia. Lung cancer—non small cell. Online. Available: http://www.cancer.org.au/Healthprofessionals/cancertypes/lungcancernonsmallcell.htm. Last updated 2003.

36 Cancer Council Australia. Lung cancer—small cell. Online. Available: www.cancer.org.au/Healthprofessionals/cancertypes/lungcancersmallcell.htm. Last updated 2003.

37 Singh M. Heated, humidified air for the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD001728.

38 Linde K, Barrett B, Wölkart K, et al. Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;1:CD000530.

39 Saxena RC, Singh R, Kumar P, et al. A randomized double blind placebo controlled clinical evaluation of extract of Andrographis paniculata (KalmCold) in patients with uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infection. Phytomedicine. 2010;17(3/4):178-185.

40 Hemilä H, Chalker E, Treacy B, et al. Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;3:CD000980.

41 Hulisz D. Efficacy of zinc against common cold viruses: an overview. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004;44:594-603.

42 Vickers AJ, Smith C. Homoeopathic Oscillococcinum for preventing and treating influenza and influenza-like syndromes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD001957.

43 World Health Organization. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. Global tuberculosis control: a short update to the 2009 report. WHO/HTM/TB/2009.426, pp. 4–5.

44 Campbell IA, Bah-Sow O. Pulmonary tuberculosis: diagnosis and treatment. BMJ. 2006;332:1194-1197.

45 Therapeutic Guidelines. Respiratory. North Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd, 2006.

46 Durrington HJ, Summers C. Recent changes in the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults. BMJ. 2008;336:1429-1433.

47 Australian Government. Australian immunisation handbook, 9th edn. 2008: 246.

48 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s health no. 9. Cat. No. AUS 44. Canberra: AIHW, 2004.