chapter 42 Skin

DIAGNOSIS

TREATMENT PLAN

IMPORTANT PITFALLS IN SKIN MANAGEMENT

SPECIFIC SKIN CONDITIONS

ECZEMA

Eczema is the most common skin reaction. It is an inflammatory disorder and the term is interchangeable with dermatitis, although sometimes ‘dermatitis’ is used when the cause is external or exogenous (Box 42.1).

Contact or exogenous eczema

Constitutional or endogenous eczema

Atopic eczema

Atopic eczema can be likened to a slow-burning scrub fire. It is much more than a steroid-responsive dermatosis. Each patient needs to be managed with an appreciation of the causes, triggers and individual patterns of their disease.

The cause of atopic eczema is probably multifactorial: genetic, immunological and environmental.

Prevention

(See also Ch 55, Child health and development.)

Treatment

These approaches are directed towards young children, but are adaptable to all age groups.

Eczema causes significant morbidity for the patient and their family.6 Treat the patient and the family as a whole. Remember the total load on the system.

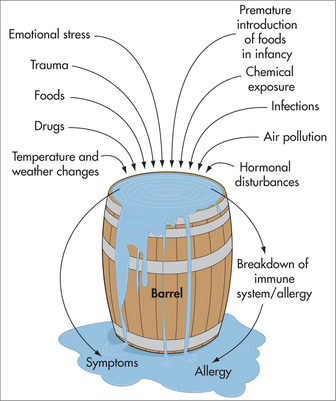

Remember that the body as a whole (including the nervous system and the mind) is always trying to heal itself, always trying to maintain balance in a life of constant ‘wear and tear’. Many factors contribute to this wearing down of the system, and the total load on the individual is always important. When the stressors on the body are too much for it to manage, the ‘barrel’ overflows and symptoms result (Fig 42.2). Stress or anxiety, therefore, having a pro-inflammatory effect, is commonly associated with exacerbations of eczema, whereas stress reduction techniques are associated with improved control and reduced exacerbations.7

PSORIASIS

Causes and triggers

Treatment

Medical treatment depends on the location:

Lifestyle factors including exercise, nutrition and stress management can all influence psoriasis.

Dietary guidelines

Nutritional supplements

Lifestyle

INFECTIONS

Viral infections

Herpes simplex

Fungal and yeast infections

INSECT BITES

Scabies

Treatment

ACNE

Most young people with acne (as with eczema and psoriasis) experience degrees of shame, embarrassment, anxiety, depression, loss of self-confidence or significant difficulty with employment. It is important that practitioners take acne seriously, treat it enthusiastically and encourage regular review.20 Patients need to be reassured that acne is not infectious, is not caused by poor hygiene, and can be controlled.

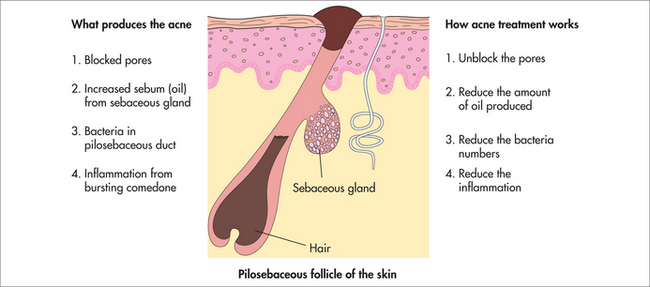

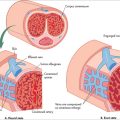

What produces acne?

Acne is produced by pores blocked with plugs of oily secretions and skin material, increased sebum (oil) from the sebaceous glands, bacteria thriving in the oily secretions, and inflammation from oil and bacteria bursting out of the comedones (Fig 42.3).

Treatment

ROSACEA

The following can be aggravants:

Treatment

Acute rosacea (with erythema and papules):

Chronic rosacea with erythema and telangiectasia—treatment is more difficult.

URTICARIA, ANGIO-OEDEMA AND ALLERGIC RASHES

Management

General measures include the following:

| Type | Causes & diagnosis | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Acute (week): likely to be allergic | Drugs: aspirin, antibiotics (beef, chicken), NSAIDs, quinine, morphine, codeine | AH |

| Insect stings: bee, wasp | ||

| Foods: salicylates, amines, benzoates, preservatives, colourings, peanut, shellfish, egg white | Avoidance | |

| Infection: focal sepsis, viral, worms, parasites, e.g. Candida, protozoa | Empirical metronidazole | |

| Idiopathic | ||

| Physical | Cold: icy water | Self-limiting, AH |

| Pressure (delayed): weights for 8 hours | Self-limiting, AH | |

| Solar: sunlight or solar stimulation | ||

| Aquagenic: water | Bicarbonate in water | |

| Cholinergic/heat: heat, exercise or stress. Five minutes of exercise will evoke < 2 mm diameter wheals | ± AH | |

| Dermographism: 2% population, most common | ||

| Chronic (years): non-allergic |

AH: antihistamines; FBE: full blood examination; HepBsAg: hepatitis B virus surface antigen; LFT: liver function test.

ENVIRONMENTAL INJURY AND SKIN CANCER

Skin cancer is the most common cancer in the body, and Australia has the highest incidence in the world. Currently 280,000 skin cancers are diagnosed each year, including 8000 melanomas. Around 1200 Australians die each year of skin cancer and the incidence continues to rise. The highest incidence of melanoma in Australia extends from Sydney up the coast to Far North Queensland. Melanomas are more likely to occur with intermittent sun exposure, such as in weekend beachgoers. Non-melanoma skin cancer is more common inland and appears to be more closely related to total sun exposure.

What causes skin cancer?

Classification

Non-melanoma skin cancer

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer and can be superficial, nodular or tough (pigmented, recurrent, infiltrating, morphoeic, desmoplastic).24 Spread is local. BCC appears as a red papule or plaque, which may have a pearly edge. The pearly edge becomes more obvious when the skin is stretched under good light.

Prevention

Treatment of premalignant lesions

Treatment of malignant skin cancer

Examine the rest of the skin after a malignant skin cancer has been diagnosed.

AGEING SKIN, DRY SKIN AND WOUND HEALING

Wound healing depends on multiple general and local factors. Healing is aided by:

SYSTEMIC DISEASES AND THE SKIN

American Academy of Dermatology. http://www.aad.org/.

Australian College of Dermatologists. http://www.dermcoll.asn.au/public/default.asp.

Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, editors. Textbook of dermatology, 7th edn, Oxford: Blackwell Science, 2004.

du Vivier A. Dermatology in practice. London: Mosby-Wolfe, 1995.

emedicine, dermatology articles. A useful website covering a wide range of dermatological conditions. http://emedicine.medscape.com/dermatology.

Gawkrodger DJ. Dermatology: an illustrated colour text. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1992. A useful and illustrated textbook of dermatology.

Hunter JAA, Savin JA, Dahl MV. Clinical dermatology. 3rd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 2002.

Marks R. Roxburgh’s common skin diseases. 16th edn. London: Chapman & Hall Medical, 1993.

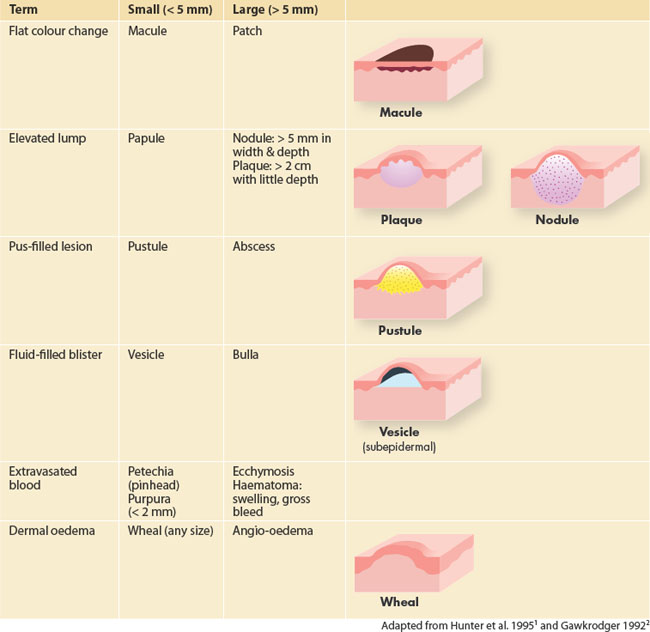

1 Hunter JC, Savin J, Dahl M. Clinical dermatology. 2nd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 1995;36.

2 Gawkrodger DJ. Dermatology: an illustrated colour text. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1992;13.

3 Pommier P, Gomez F, Sunyach MP, et al. Phase III randomized trial of Calendula officinalis compared with trolamine for the prevention of acute dermatitis during irradiation for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(8):1447-1453.

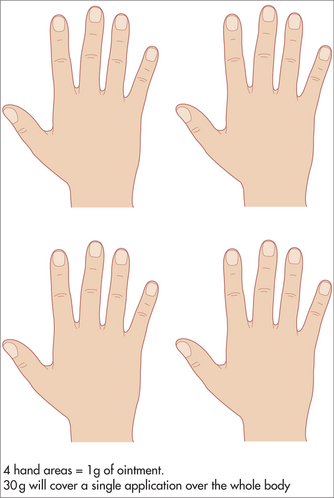

4 Long CC, Findlay AY. The rule of hand. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:1129-1130.

5 Surh Y, Lee J, Choi K, et al. Effects of selected ginsenosides on phorbol ester-induced expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and activation of NF-kappaB and ERK1/2 in mouse skin. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;973:396-401.

6 Holm EA, Wulf HC, Stegmann H, et al. Life quality assessment among patients with atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154(4):719-725.

7 Hoare C, Li Wan Po A, Williams H. Systematic review of treatments for atopic eczema. Health Technol Assess. 2000;4(37):1-191.

8 Michaelsson G, Kristjansson G, Pihl Lundin I, et al. Palmoplantar pustulosis and gluten sensitivity. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(4):659-666.

9 Berbis P, Hesse S, Privat Y. Essential fatty acids and the skin. Allerg Immunol (Paris). 1990;22(6):225-231.

10 Weiss R, Fintelmann V. Herbal medicine. 2nd edn. Stuttgart: Thieme, 2000.

11 Strimpakos A, Sharma R. Curcumin: preventive and therapeutic properties in laboratory studies and clinical trials. Antiox Redox Signal. 2008;10(3):511-545.

12 Choonhakarn C, Busaracome P, Sripanidkulchai, et al. A prospective, randomized clinical trial comparing topical aloe vera with 0.1% triamcinolone acetonide in mild to moderate plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(2):168-172.

13 Brown AC, Hairfield M, Richards D, et al. Medical nutrition therapy as a potential complementary treatment for psoriasis—five case reports. Altern Med Rev. 2004;9(3):297-307.

14 Shin Y-W, Bae E-A, Kim D-H. Inhibitory effect of ginsenoside Rg5 and its metabolite ginsenoside Rh3 in an oxazolone-induced mouse chronic dermatitis model. Arch Pharm Res. 2006;29(8):685-690.

15 Vasange-Tuominen M, Perera-Ivarsson P, Shen J, et al. The fern Polypodium decumanum, used in the treatment of psoriasis, and its fatty acid constituents as inhibitors of leukotriene B4 formation. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1994;50(5):279-284.

16 Anon. Coleus forskohlii. A monograph. Altern Med Rev. 2006;11(1):47-51.

17 Tse W. Use of common Chinese herbs in the treatment of psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28(5):469-475.

18 Al-Gurairi FT, Al-Waiz M, Sharquie KE. Oral zinc sulphate in the treatment of recalcitrant viral warts: randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146(3):423-431.

19 Schneider S, Reichling J, Stintzing F, et al. Anti-herpetic properties of hydroalcoholic extracts and pressed juice from Echinacea pallida. Plant Med. 2010;76(3):265-272.

20 Basra MKA, Sue-Ho R, Finlay AY. The Family Dermatology Life Quality Index: measuring the secondary impact of skin disease. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(3):528-538.

21 Heffernan MP, Nelson MM, Anadkat MJ. A pilot study of the safety and efficacy of picolinic acid gel in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(3):548-552.

22 Amman W. Acne vulgaris and Agnus castus (Agnolyt). Z Allgemeinmed. 1975;51(35):1645-1648.

23 Mills S, Bone K. Principles and practice of phytotherapy. Modern Herbal Medicine. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

24 Dixon AJ, Hall SH. Managing skin cancer. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34(8):669-671.