Chapter 58 Vulvar and Vaginal Carcinoma

Vulvar Carcinoma

Historically, radical vulvectomy and en bloc bilateral inguinal node dissection was the standard approach for the majority of patients, regardless of disease extent.5–8 Consequent to the chronic, often debilitating physical and psychological sequelae of radical vulvectomy in long-term survivors, questions arose regarding the need for radical vulvectomy in patients with limited disease at diagnosis. Unsatisfactory rates of locoregional control in patients with advanced disease as well as the morbidities associated with exenterative surgery stimulated exploration of novel combinations of therapies. Increasing awareness of the sensitivity of squamous vulvar cancer to RT and chemoradiation further suggested management changes.

Etiology and Epidemiology

No universal cause for vulvar cancer has been identified. The etiology is likely multifactorial, but some risk factors have been identified. Many patients with vulvar carcinoma have had previous malignant or premalignant lesions of the genital tract.9–11 Between 2% and 5% of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) 3 lesions (severe dysplasia or carcinoma in situ) will progress to invasive carcinoma.12 The risk factors for progression to invasive cancer are poorly understood but do include advanced age. One study observed that the relative risk for vulvar or vaginal carcinoma after treatment of cervical carcinoma was 2.9% regardless of whether the patient received radiation for treatment of the cervical cancer. Compromised immune status, whether iatrogenic in the setting of organ transplantation, congenital, or acquired based on human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, leads to an increased risk for cancers in the lower genital tract, including the vulva and vagina. Improvement in immune function with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) may decrease the risk in HIV-infected patients,13–22 although longer survival with HAART may permit emergence of papillomavirus-associated anogenital malignancies in long-term survivors of HIV infection.23

The human papillomavirus (HPV) has been implicated as a cause of vulvar cancer. Brinton and colleagues24 established a relative risk of vulvar cancer of 14.6% when there is a history of condylomata acuminata. HPV has been detected widely in sexually active women. The type of HPV is related to the risk for benign versus malignant tumors of the vulva. In patients with condylomata acuminata, the detected HPV is usually type 6 or 11, whereas for vulvar in-situ neoplasia or vulvar carcinoma, HPV 16 and 18 are more common.25,26 Invasive vulvar cancer and condyloma may be present synchronously in the same patient, delaying diagnosis of malignancy in some patients. Multiple studies have investigated the presence of HPV in vulvar carcinoma.27,28 It may be detected in both primary tumors and nodal metastases. Review of published data29 employing polymerase chain reaction or hybrid capture assays for HPV DNA detection in 2790 patients with invasive vulvar cancer—1320 patients with VIN 2 and 3, and 71 patients with VIN 1—reveals HPV prevalence in invasive cancer to be 40.1% in invasive lesions, 80.4% in VIN 2 and 3, and 77.7% in VIN 1. HPV 16 serotype was the most common, detected in 29.3% of invasive cancers and 71.2% of VIN 2 and 3 lesions.

Smoking is an additional risk factor for vulvar carcinoma as it is with cervical cancer, and the combination of smoking with a history of genital warts results in a strong increase in the relative risk for vulvar cancer.11,30 It is possible that smoking and HPV infection have a synergistic effect on the genesis of vulvar cancer, with smoking functioning as a promoter.31,32

Data are conflicting as to the etiologic role of vulvar dystrophies (lichen sclerosus and squamous cell hyperplasia) in the cause of vulvar cancer. These epithelial alterations may be seen in approximately half of patients with vulvar cancer.33–35 Patients with vulvar cancer and associated lichen sclerosus are, on average, significantly older than patients with newly diagnosed lichen sclerosus with or without squamous hyperplasia.36 However, less than 5% of patients with these epithelial alterations will progress to invasive vulvar malignancy.

It has been observed that there are two, broadly different groups of vulvar cancer patients. The first consists of younger patients who more frequently smoke and are at higher risk for HPV infection and whose invasive cancers are commonly associated with VIN. The second, and more common, group consists of elderly patients whose disease may be unrelated to smoking or HPV infection and in whom concurrent VIN is unusual but lichen sclerosus and squamous hyperplasia are common associated findings.37

Investigators have examined a number of molecular and genetic parameters in an effort to define prognostic factors in patients with invasive cancer, as well as to identify patients with lichen sclerosus, squamous hyperplasia, or VIN who are at highest risk for development of invasive malignancy.38–45,46 However, at this time, the use of molecular markers has not become a part of routine clinical practice.

Prevention and Early Detection

No known measures to prevent invasive vulvar cancer exist except for the appropriate treatment of VIN when it is detected. Whether treatment of lichen sclerosus and squamous hyperplasia reduces the risk of subsequent development of invasive cancer is unknown. Pooled data from three prospective clinical trials with mean follow-up of 42 months after initiation of vaccination with quadrivalent HPV vaccine (HPV types 6/11/16/18) show 100% efficacy in prevention of VIN 2 and 3 and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) 2 and 3 among patients treated per protocol and 79% in an intent-to-treat population (HPV exposed and unexposed).47 Whether this will ultimately translate into a clinically meaningful reduction in the incidence of preinvasive and invasive vulvar and vaginal malignancies remains specultative.48 At this time, the target population for whom efficacy would seem most likely consists of sexually naive/HPV unexposed adolescents.

A history of smoking tobacco products is associated both with VIN and invasive vulvar malignancy. Patients who smoke should be encouraged to quit, because the statistical risk of anogenital malignancy associated with former smoking is observed to be substantially less than that associated with current smoking and diminishes with increasing time since cessation of smoking.32 Additionally, women with vulvar or vaginal cancer appear to have a fourfold increased risk of subsequently developing a second primary cancer of the lung.49

Because VIN 3 may be associated with an occult invasive lesion in as many as 20% of symptomatic patients,50 care must be taken when employing treatment techniques that do not include full-thickness histologic evaluation. Excisional techniques, provided that there is minimal loss of functionality and cosmesis, are preferable to ablative techniques without histologic material for study. Core biopsy or excisional biopsy of smaller lesions is suggested for most vulvar abnormalities, if necessary under colposcopic guidance. In circumstances in which there exists a strong clinical suspicion of an invasive cancer, a core biopsy is preferable to an excisional biopsy, in order to preserve the diagnostic accuracy of a subsequent sentinel node procedure. Even if vulvar lesions appear to have a warty appearance and are believed to be benign, confluent warts should be sampled to exclude an underlying diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma.

Pathology and Pathways of Spread

Pathology

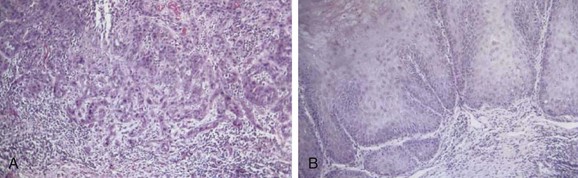

Squamous cancer is the most common malignant lesion of the vulva and constitutes 80% to 90% of vulvar tumors. It may be unifocal or multifocal. Variants of squamous cancer include cancers with discontiguous, infiltrative borders permeating lymphatic spaces with a so-called spray pattern of local invasion51,52 and verrucous cancers with broad, pushing borders53,54,55,56 (Fig. 58-1). Sarcomatoid differentiation is seen in a minority of squamous cancers and can be associated with an aggressive course.

Verrucous cancers may clinically manifest a warty appearance resembling a cauliflower floret, with exuberant hyperkeratosis microscopically. Broad, bulbous borders characterize these tumors, which rarely metastasize to regional nodes. Morphologic and biologic studies on 10 cases of verrucous carcinoma of the vulva support the theory that verrucous cancers constitute a discrete clinicopathologic subset of vulvar cancer.57 Treatment is radical local excision. Despite a tendency for these tumors to recur locally, the role of radiotherapy as adjuvant treatment for this variant remains controversial because of anecdotal reports of clinical radioresistance.

Other, much less common tumors found in the vulva include malignant melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, Merkel cell tumors, carcinoid, transitional cell carcinomas, adenoid cystic carcinoma, vulvar Paget’s disease, and a variety of sarcomas. Tumors metastasizing from other sites may become manifest in the vulva.58

Melanomas constitute less than 10% of primary tumors but are the second most common malignancy of the vulva. Even clinicians at tertiary referral centers will see only one or two patients with melanoma of the vulva annually. Melanomas may arise de novo or from preexisting junctional or compound nevi. Rare, amelanotic vulvar melanomas may occur. Diagnostic assessments, staging, and treatment broadly parallel the that for cutaneous melanoma arising at other sites. Prognosis correlates with depth of invasion59–61 and with the presence or absence of spread to regional nodes. Locoregional therapy is primarily surgical.

Primary malignant tumors of the vulva may arise in the Bartholin complex, and some of these are variants of adenocarcinomas. Adenoid cystic carcinomas uncommonly disseminate to regional nodes and may have an indolent natural history with late local and hematogenous relapse.62 Perineural invasion is common. Tumors in the Bartholin complex also may be squamous and are thought to arise in ductal squamous epithelium.

Bartholin’s tumors tend to be deeply infiltrative and solid, often with the overlying skin remaining intact. This clinical presentation may be confused with benign cysts or infection, causing delay in diagnosis and difficulty in accomplishing surgical clearance with wide, negative margins because of proximity to the anorectum and the ischial ramus. Observational outcomes data suggest that patients with Bartholin’s tumors that are more locally extensive are less likely to manifest local failure when postoperative adjuvant RT is administered compared with patients with more favorable disease treated with surgery as monotherapy.62

The International Society for the Study of Vulvar Disease (ISSVD) recommended abandoning the term microinvasion when applied to carcinoma of the vulva and proposed the current use of stage IA, which incorporates criteria for both tumor size and depth. The depth of invasion is defined as the distance from the epithelial stromal junction of the most superficial adjacent dermal papillae to the deepest point of invasion. Stage IA is defined as a solitary squamous cancer of the vulva measuring less than 2 cm in diameter, with clinically negative nodes in which the depth of invasion is 1 mm or less.63,64 This definition encompasses the previous understanding of microinvasion, because the risk of nodal involvement with invasion less than 1 mm is close to 0%. In addition to tumor stage and depth, other pathologic features of the primary tumor should be noted, including presence or absence of vascular space invasion, tumor grade, and tumor growth pattern.65

Pathways of Spread

Vulvar cancer spreads by direct extension to adjacent structures, including the vagina, urethra, perineum, anus, and ischial rami. Tumor may spread by embolization through the lymphatics to the regional nodes. Permeation of in-transit regional lymphatic vessels is uncommon but may account for the occasional patient with recurrence in the skin bridge conserved when vulvar cancer is treated surgically employing separate incisions for the primary tumor and the regional node dissection. This is rare in the absence of extensive groin node metastases.66

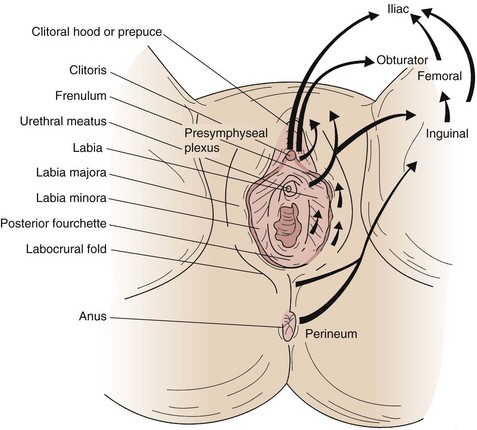

The lymphatics of the vulva (Fig. 58-2) consist of a network that covers the entire labia minora, fourchette, prepuce, and distal vagina below the hymenal membrane. Lymphatics coalesce anteriorly, forming larger trunks, which run lateral to the clitoris to the mons veneris, acquiring tributaries from the lymphatics of the labia majora, which run in a parallel fashion anteriorly from the perineal body. At the mons veneris, the vulvar lymphatic trunks diverge laterally to the inguinal nodes. Study of the localization of dye or radiolabeled tracer in regional lymph nodes after focal injection of discrete sites in the vulva and on the perineum reveals that the lymphatic drainage of the perineum, clitoris, and anterior labia minora is often bilateral whereas the lymph flow from well-lateralized sites (>2 cm from midline structures) in the vulva is predominantly to the ipsilateral groin.67

Figure 58-2 Lymphatic drainage of the vulva and perineum. Arrows indicate the flow patterns.

Adapted from Russell AH: Cancer of the vulva. In Leibel SA, Phillips TL (eds): Textbook of Radiation Oncology, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 2004, p 1179.

Primary lymphatic drainage is usually to the superficial inguinal nodes with secondary lymphatic drainage through the cribriform fascia to the femoral nodes, with subsequent tertiary flow under the inguinal ligaments to the external iliac nodes. However, metastases have been reported to the femoral lymph nodes without involvement of the superficial inguinal lymph nodes,68,69 especially from carcinomas of the clitoris and Bartholin’s gland. Sentinel node studies have demonstrated primary lymphatic flow to deep nodes in as many as 16% of cases,70 and a Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study also found an unexpectedly high incidence of ipsilateral groin recurrences secondary to presumed involvement of lymph nodes deep to the cribriform fascia despite prior negative superficial inguinal lymphadenectomy.71 The actuarial risk of groin recurrence at 5 years was 16% (19/119) among patients with vulvar cancer treated with groin node dissection alone at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, of whom 111 had superficial inguinal node dissections. Of these patients, 117 had groin specimens histopathologically negative for metastases.72 Groin recurrence after superficial and deep groin dissection retrieving histologically negative nodes is 2% or less.73–75

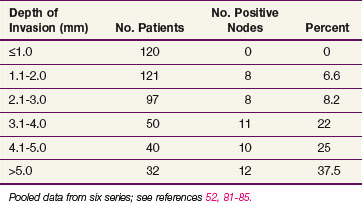

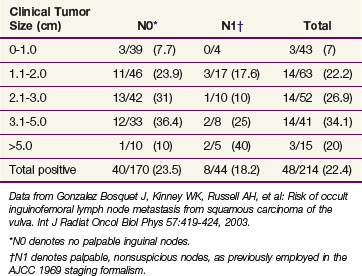

Clinical assessment of groin node status by palpation is notoriously inaccurate, with approximately 20% of groins judged clinically nonsuspicious harboring occult node metastases and approximately 20% of groins considered clinically suspicious for metastases containing only reactive or inflammatory nodes* (Table 58-1). The frequency of lymph node metastases to the inguinal-femoral nodes is related to the depth of stromal invasion52,81–85 (Table 58-2), defined as the distance from the epithelial stromal junction of the most superficial adjacent dermal papillae to the deepest point of invasion. In Table 58-3 the incidence of occult nodal involvement in clinically nonsuspicious groin nodes treated by complete lymphadenectomy is cross-tabulated by primary tumor size.86

TABLE 58-1 Clinical Assessment of Inguinofemoral Nodes by Palpation

| Node Status | Histologically Negative | Histologically Positive |

|---|---|---|

| Clinically negative (451 patients) | 363 (80.5%) | 88 (19.5%) |

| Clinically positive (243 patients) | 53 (21.8%) | 190 (78.2%) |

Pooled data from six institutions; see references 7, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80.

TABLE 58-2 Incidence of Groin Node Metastasis Correlated with Depth of Invasion for Primary Tumors 2 cm or Smaller

TABLE 58-3 Probability of Clinically Occult Metastasis to Inguinofemoral Lymph Nodes Correlated with Primary Tumor Size in Operable Vulvar Cancer

With lateralized primary tumors, metastases to the contralateral groin in the absence of ipsilateral groin metastases may be seen in up to 15% of patients with very advanced primary disease.87 Metastases to contralateral groin nodes in the setting of uninvolved ipsilateral groins have been reported in patients with Bartholin’s gland primary disease88 and tumors of the anterior labia minora.83 In the absence of spread to ipsilateral nodes, discrete (≤2 cm diameter), well-lateralized primary cancers limited to the vulva and not approaching midline structures manifest spread to contralateral groin nodes in less than 1% of patients undergoing bilateral lymphadenectomy.82–85,89–91 However, 5 patients (2.6%) of 192 pooled patients with T1 lateralized cancers managed with ipsilateral groin dissection with no evidence of nodal disease have manifested contralateral groin recurrence.71,85,92–96 A theoretic explanation for this discrepancy is the possibility that dissection of negative groin nodes may be therapeutic in a small number of patients in whom routine sectioning of groin nodes (as opposed to pathologic ultrastaging) may fail to detect minute micrometastases consequent to undersampling.

The overall incidence of metastases to the pelvic lymph nodes is 5%. Lymphadenectomy will detect metastatic involvement in pelvic nodes in 15% to 28% of patients with metastases to inguinal nodes.* Pelvic node metastasis is extremely rare in the absence of groin node metastases and very uncommon in the context of occult, microscopic involvement of a single groin node.

Hematogenous spread, usually to lung and bone, is unusual in the absence of prior inguinofemoral lymph node involvement and generally occurs late in the course of the disease. Most patients who die of disease do so with uncontrolled locoregional disease. However, in patients with three or more positive lymph nodes the ultimate risk of hematogenous spread is 66%. In contrast, patients with fewer than three positive lymph nodes have only a 4% risk of hematogenous spread.102,103

Biology and prognostic factors

In multivariate analysis the presence or absence of lymph node involvement remains the single most important prognostic factor in outcomes of treatment for vulvar cancer.104 For those with negative lymph nodes, the average 5-year overall survival (OS) from nine large literature series is 91% (range, 83% to 100%).† For those with involved lymph nodes treated with curative intent, the average 5-year OS is 52% (range, 38% to 61%).‡ Ninety-five percent of relapses after primary surgical treatment occur in the vulva, perineum, or groins.73,82,109–112 The extent of lymphatic involvement is prognostic and includes volume of tumor in the involved nodes, extracapsular penetration, number of positive nodes, and level of metastatic disease in the nodal chain.3,4,28,105,113

A number of primary tumor-related characteristics, identified on multivariate analysis, predict for vulvar relapse regardless of nodal involvement, among them tumor size and depth of invasion.77 The latter correlates not only with locoregional recurrence but also with the risk of node metastasis. Heaps and colleagues65 identified stage, width of surgical margin, depth of invasion, tumor thickness, growth pattern (infiltrative as opposed to pushing), and presence of vascular space invasion as factors predictive of local recurrence after primary surgery.

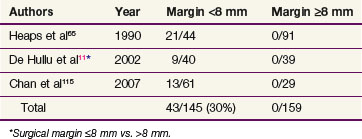

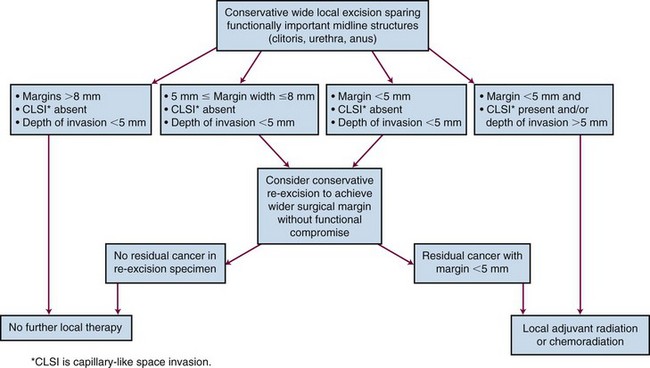

Three publications65,114,115 have reported a clear association between risk of vulvar recurrence and width of surgical resection margins. When microscopic margins are 8 mm or less in formalin-fixed tissue, local recurrence has been observed in 43 of 145 patients (30%)65,114,115 (Table 58-4). These findings have not, however, been consistently observed in all pathology laboratories.116 Allowing for estimated fixation shrinkage artifact between 25% and 45%, this 8-mm pathologic margin correlates with a minimal clinical free space of 1 cm of uninvolved normal tissue, providing a practical guideline for identifying patients who are likely to be advised to undergo postoperative local irradiation for inadequate margins if treated by initial surgery. Under such circumstances, preoperative chemoradiation may be preferable to secure better margins and possibly to reduce the scope of subsequent conservative surgery.

Clinical Manifestations, Patient Evaluation, and Staging

Clinical Manifestations

The virus-related cause of vulvar cancer in some patients, its association with preinvasive or invasive cancers in other parts of the lower genital tract, and its histologic features suggest that vulvar cancer may be one manifestation of a multifocal disease or “field cancerization.”46,117 However, at the time of diagnosis only about 5% of vulvar cancers are multifocal. Patients usually present with a vulvar mass or ulcer often following a variable history of pruritus or vulvar pain. Depending on the location and size of the lesion within the vulva, the patient may also complain of dysuria, difficulty with defecation, bleeding, or discharge. Rarely, patients may present with advanced inguinal node involvement, occasionally with ulcerating masses in the groins or with lower extremity lymphedema resulting from obstruction.

Patient Evaluation

Clinical evaluation of the groin nodes by palpation is inaccurate in approximately 20% of cases. Clinically negative nodes will harbor occult metastases in approximately 20% of cases, and approximately 20% of patients with clinically positive groin nodes will have negative nodes if surgically dissected, presumably because of the confounding presence of inflammatory or reactive changes (see Table 58-1). Assessment of groin nodes is particularly compromised in the obese patient, when even superficial inguinal nodes may be several centimeters below the skin. Because of the imprecision of clinical assessment, pathologic verification of nodal status is desirable, when feasible, and is required for assignment of FIGO stage.

Staging

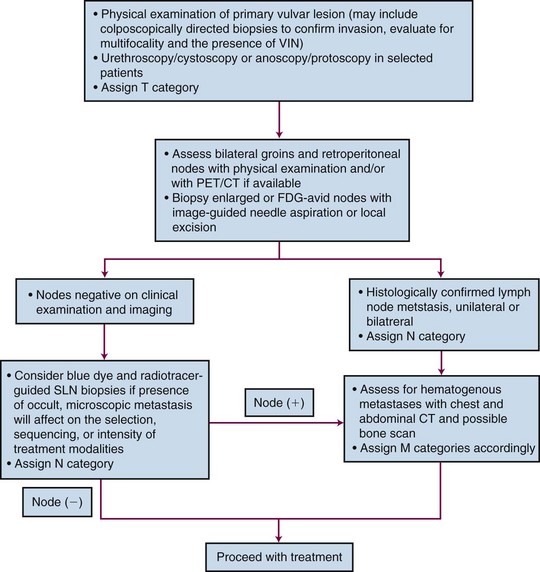

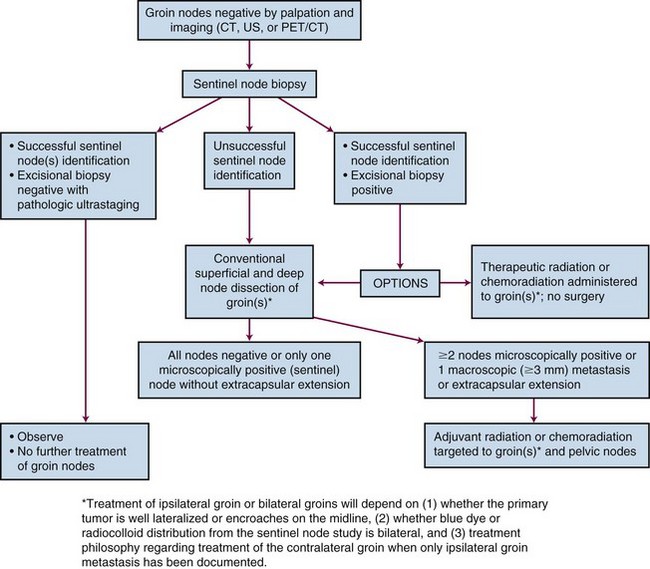

In 1988, FIGO introduced a surgical staging system for vulvar cancer that has since undergone several revisions, most recently in 2009 (Table 58-5). Staging systems are intended to standardize reporting of treatment efficacy, allowing comparison of the outcomes of treatment from different institutions and comparison of results employing different treatment strategies. Ideally, stage should not be employed to determine therapy and should be assigned prior to any major therapeutic intervention such as surgery. Unfortunately, the current clinicopathologic system defines stage for many patients based, in part, on information derived subsequent to surgical treatment of the groin nodes. Because of the strong association between prognosis and the number and size of groin node metastases, the staging system appears to implicitly endorse surgical management of the groin nodes when this may not be prudent or feasible in all clinical circumstances. In a patient with a locally advanced primary tumor requiring preoperative chemoradiation in an effort to avoid compromise of functionally important midline structures, it may be medically sensible to electively include clinically negative groin nodes in the irradiated volume, provided that they appear grossly uninvolved by physical examination and diagnostic imaging. Without subsequent groin dissection and without sampling of groin nodes prior to treatment, such patients are reported to have a very low probability of treatment failure of groin disease if treatment is carried out with appropriate technique.118,119 Such patients are, however, “unstaged.” Comprehensive pretreatment evaluation of disease extent may be less important when institutional treatment policy is to perform initial surgery in all patients with medically operable and technically resectable disease, even in the presence of limited node metastases. If the detection of nodal disease before treatment will impact the selection, sequencing, or intensity of treatment modalities, the diagnostic cascade illustrated in Figure 58-3 may help to guide therapy. No consensus standard exists for the pretreatment evaluation of disease extent. PET/CT may not be available in many locations, and lack of reimbursement may prove an additional obstacle even when the technology is available for other indications. Experience with sentinel node identification is not universal, and its routine use outside tertiary referral centers remains controversial. Thus the algorithm in Figure 58-3 may not be applicable in all venues.

| Stage | Description |

| I | Tumor confined to the vulva |

| IA | Lesions ≤2 cm, confined to the vulva or perineum and with stromal invasion ≤1.0 mm*; no nodal metastasis |

| IB | Lesions >2 cm or with stromal invasion >1.0 mm,* confined to the vulva or perineum, with negative nodes |

| II | Tumor of any size with extension to adjacent perineal structures (one-third lower urethra, one-third lower vagina, anus) with negative nodes |

| III | Tumor of any size with or without extension to adjacent perineal structures (one third lower urethra, one third lower vagina, anus) with positive inguinofemoral lymph nodes. |

| IIIA |

* The depth of invasion is defined as the measurement of the tumor from the epithelial-stromal junction of the adjacent most superficial dermal papilla to the deepest point of invasion.

From Pecorelli S: Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 105:103-104, 2009.

Because lymphatic drainage from the anterior labia minora may be bilateral,67,120 bilateral groin assessment should be considered for lesions arising in these areas even if otherwise apparently lateralized because contralateral groin metastases with negative ipsilateral groin nodes have been described with primary tumors in this location.83 Possibly because precise tumor extent may be more difficult to appreciate on physical examination, contralateral groin node metastases with negative ipsilateral groin nodes have similarly been reported in patients with primary cancers of the Bartholin complex, suggesting consideration of bilateral histologic groin assessment in such patients as well.88

Sentinel nodes (Fig. 58-4) may be identified for selective excisional biopsy by injection of blue dye and radiocolloid at the primary site.70,121–126 It is increasingly clear that use of a blue dye alone is insufficient to identify sentinel nodes. Results are better when a radioactive tracer is used in combination with blue dye. Sentinel nodes should be both “hot and blue” for greatest accuracy. When sentinel nodes are enlarged or heavily infested with metastatic cancer, a sentinel node study may be falsely negative consequent to altered patterns of lymphatic flow. Imaging of the groins before identification of the sentinel node, with ultrasonography or CT, should reduce the probability of a false-negative sentinel node study by identifying grossly enlarged or suspicious nodes, which may or may not be palpable, whose status requires clarification regardless of the findings from a sentinel node study.

Pathologic ultrastaging of groin nodes has been used to increase the sensitivity of sentinel node excisional biopsy in the detection of microscopic groin node metastases.124,127 Ultrastaging may include thin step-sectioning of retrieved nodes with or without immunohistochemical staining. When nodal disease is advanced and initial surgery to the groin area is not planned, histologic confirmation of metastatic contamination may be obtained by fine-needle biopsy or aspiration cytology.

Noninvasive imaging with PET/CT, MRI, or ultrasonography may assist in assessing lymph node status, particularly in larger or obese patients in whom femoral nodes may be many centimeters below the skin and well beyond a depth where node palpation is feasible.128–131 Metabolic imaging may sometimes detect metastases in the absence of gross nodal enlargement. CT alone is less sensitive owing to the frequency with which groin nodes are nonspecifically enlarged due to inflammatory or reactive changes and/or fat replacement. Spatial imaging may identify nodes accessible for image-guided fine-needle biopsy. Although clinically useful in some patients, the results of imaging assessment, unless confirmed histologically, do not alter assignment of FIGO stage. Accurate measurement of the depth of femoral nodes below the anterior skin surface at the level of the femoral artery as it passes under the inguinal ligament is critical in the design and implementation of radiation-based therapy for undissected groins as well as in the context of adjuvant irradiation of the groins after superficial or total inguinal lymph node dissection.132,133 Axial imaging is probably the most precise means of making this measurement.

Primary Therapy

The treatment of patients with vulvar cancer has been in a state of evolution for more than 3 decades. Previously, radical vulvectomy with en bloc bilateral groin dissection with or without bilateral pelvic node dissection was the treatment of choice for all patients with vulvar cancer.5–7 Although extirpative surgery improved cancer outcomes compared with results obtained during previous eras, it was associated with substantial acute and chronic postoperative morbidity as well as major psychological sequelae. Leg lymphedema after radical groin and pelvic node dissection may be either temporary or permanent and disabling.97,134 Pelvic relaxation, organ prolapse, and urinary incontinence can develop in some patients, particularly when removal of the distal urethra or a portion of the lower vagina is required to achieve surgical clearance. Vaginal introital stenosis can occur, and the absence of the vulva and venereal fat can have the functional equivalence of shortening effective vaginal depth and removing a protective cushion from the pubic arch. These changes may contribute to dyspareunia in many patients. Additionally, removal of the clitoris will profoundly diminish capacity for sexual arousal and climax. The psychosexual consequences of vulvectomy are frequently devastating.135–137

The clinical extent of vulvar cancer at the time of diagnosis may be decreasing, possibly consequent to more enlightened attitudes regarding the pathogenesis of the disease and improved access to health care. Among patients with operable disease undergoing radical groin dissection, the frequency of lymph node metastasis decreased from approximately 50% in reports from the 1940s and 1950s6,138 to approximately 30% in surgical literature from the 1970s and 1980s.3,78,105–107 As younger, sexually active patients were being diagnosed with preinvasive disease or unifocal disease of minimal volume and depth of invasion, modifications in the surgical approach to vulvar cancer were provoked by concerns about the chronic morbidities of radical vulvectomy, particularly in patients with disease of limited extent.

Refined understanding of pathologic predictive factors, patterns of failure after standard radical surgery, and efficacy and tolerability of radical radiation in vulvar cancer has led to progressive change from the recommendation for radical surgery in all patients. The focus of vulvar cancer management has moved toward decreasing the morbidity and mortality of radical vulvectomy in patients with early-stage, prognostically favorable tumors, and improving results without increasing morbidity in patients with advanced, poor-prognosis disease by using integrated multimodality therapy that includes irradiation, chemotherapy, and functionally conservative surgery.8 The diversity of the disease and the afflicted patients requires tailoring the nature and extent of treatment to the location and severity of the cancer while being cognizant of the activity, efficacy, and toxicity of each available treatment modality used alone or in combination.

Surgical Trends Including Sentinal Node Studies

Radical surgery for vulvar cancer has moved away from the classic radical vulvectomy with en bloc bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection toward less extensive vulvar and groin surgery, particularly in patients with early-stage lesions. Indicators of this trend include the use of separate vulvar and groin incisions (so-called triple incision) with preservation of the intervening skin bridges; use of less comprehensive groin node surgery coupled with irradiation in patients with gross inguinofemoral node metastases; and pelvic irradiation in lieu of pelvic node dissection superior to the inguinal ligament in patients with confirmed groin node metastases.84,90,139,140 The definition of radical vulvar surgery has changed with the realization that the efficacy of radical surgery may best be defined by the closest resection margin65,114,115,141 rather than by achievement of total organ ablation (vulvectomy).

In patients with limited disease and clinically negative groin nodes or occult groin node metastases, utilization of separate incisions for the primary and groins is associated with decreased acute and chronic morbidity without compromise of disease-specific (DSS) or OS compared with en bloc resection.142 However, when corrected for other prognostic variables in a multivariate analysis, the type of surgical treatment (triple incision vs. en bloc) was an independent predictor for vulvar recurrence but not for inguinal/pelvic relapse.143 The lack of impact on DSS and OS may be attributed to high salvage rates for isolated vulvar recurrence reported in some clinical series,111,144 although 2-year actuarial survival after vulvar recurrence has been reported to be as low as 25% and uncontrolled local recurrence was a contributing cause of death in 15 of 16 patients dying of cancer in one series.141 Risk of recurrence in preserved skin bridges appears related to trapped dermal lymphatic emboli in patients with extensive groin adenopathy and is rare in the absence of groin adenopathy because lymphatic dissemination in vulvar cancer is characteristically embolic rather than permeative.

Radical excision for invasive tumors extends to the level of the deep perineal fascia usually 1 to 2 cm below the skin. Although there is some uncertainty about the optimal extent of surgical margin after wide local excision, data from three clinical series reveal high local control rates for cases in which the surgical margin was greater than 8 mm in the fixed state postoperatively (see Table 58-4). This suggests that, in the nonfixed state, tumor margins of at least 1.0 to 1.5 cm in all dimensions are desirable to achieve high local control rates. Many clinicians endorse a margin of 1.5 to 2 cm.

Effective management of the inguinal nodes is essential because approximately 95% of patients who experience relapse in regional lymph nodes after unsuccessful initial therapy will ultimately die of cancer.* Patients whose primary lesion in the vulva invades to a depth less than 1 mm and is smaller than 2 cm (stage IA) have a negligible risk of groin node metastasis and do not require exploration and management of the inguinal region52,81–85 (see Table 58-2). In every patient with a primary tumor larger or more deeply invasive (≥ stage IB), surgical treatment must include the ipsilateral groin dissection unless a successful sentinel node study confirms at least one negative sentinel node. For patients with well-lateralized primary tumors, preferably 1.5 cm or more from midline structures, treatment of the contralateral groin may be omitted unless the ipsilateral groin is contaminated.

The move toward more conservative, tailored surgical management has led to changes in the extent of groin dissection and the use of unilateral groin dissection for selected patients. The standard radical bilateral inguinofemoral lymph node dissection, including both superficial and deep nodes, results in as much as a 50% incidence of acute wound breakdown, lymphangitis, or lymphocyst formation and a 10% to 25% incidence of chronic lower extremity lymphedema.77,97,134,148 The surgical morbidity associated with limited, superficial groin dissections is generally acknowledged to be less than that associated with superficial and deep dissections.139 The rationale for limiting the extent or depth of groin dissection relates to the somewhat orderly sequence of metastatic progression in the groin nodal chain and the observation that involvement of the deep femoral nodes without involvement of the superficial nodes is uncommon. However, the actuarial risk of groin recurrence at 5 years was 16% among vulvar cancer patients treated with superficial groin node dissection alone at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center72 and anatomic study of sentinel node location has shown that sentinel nodes will include deep femoral nodes in as many as 16% of patients.70 Surgical results might be improved by extending the superficial groin dissection to remove the medial portion of the cribriform fascia and underlying femoral nodes en bloc with the superficial inguinal fat pad.149 Routine study of sentinel nodes by combined injection of blue dye and lymphoscintigraphy might further reduce the risk of groin failure by identifying the minority of patients with direct lymphatic pathways to deep nodes.70,121–126

If careful study of sentinel nodes shows no evidence of tumor contamination, full therapeutic groin dissection may be sensibly omitted in patients with discrete, unifocal tumors less than 4 cm in diameter because subsequent groin relapse will be rare. A large international observational study (GROINSS-V, GROningen INternational Study on Sentinel nodes in Vulvar cancer) on sentinel node detection using radioactive tracer and blue dye was conducted in 15 institutions. Team skill verification in sentinel node biopsy technique was required before patient enrollment. Patients with a unifocal primary tumor confined to the vulva and less than 4 cm in diameter with one or more sentinel nodes identified and histologically negative by ultrastaging had their disease treated by vulvar surgery without groin dissection. A total of 623 groins were studied in 403 assessable patients. Among 259 patients meeting criteria for groin observation, six groin recurrences were subsequently diagnosed (2.3%). Short-term morbidity was decreased in patients after sentinel node dissection only, compared with patients who had a positive sentinel node biopsy who underwent complete inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy. Acutely, groin wound breakdown was seen in 11.7% of sentinel node biopsy–only patients versus 34.0% of patients undergoing complete groin dissection. Cellulitis was observed in 4.5% versus 21.3% of patients, respectively. Chronic morbidity also was less frequently observed after removal of only the sentinel node compared with sentinel node removal and inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy. Recurrent erysipelas was seen in 0.4% versus 16.2% of patients, respectively, and lymphedema of the legs was observed in 1.9% of patients undergoing sentinel node biopsy versus 25.2% of patients undergoing full groin dissection. The 3-year DSS rate for patients with unifocal disease and negative sentinel nodes was 97%.150

A parallel multi-institutional study of the diagnostic accuracy of the sentinel node procedure was conducted in the United States by the GOG (GOG 173), which enrolled 510 patients from 47 institutions beginning in December 1999. Importantly, skill verification in sentinel node biopsy technique was not required before study participation, and patients with primary cancers 2 to 6 cm in diameter were included. Initially the node identification was accomplished by blue dye technique with lymphoscintigraphy optional, but in 2001 the protocol was amended to require preoperative lymphoscintigraphy with intraoperative radiolocalization. After sentinel node retrieval, groin dissection was performed to define the sensitivity (true positive/true positive + false negative), negative predictive value (true negative/true negative + false negative), and false-negative predictive value (1 − negative predictive value) associated with this technique. In preliminary analysis of 411 fully reviewed and assessable patients of whom 129 had groin node metastases, the sentinel node biopsy sensitivity was 89.9%, the negative predictive value was 95.6%, and the false-negative predictive value was 4.4%.151 The false-negative rate was 6.9% for patients with primary tumors less than 4 cm in diameter and 14% in patients with tumors of 4 to 6 cm.151

If one or more sentinel nodes were involved with tumor in the GROINSS-V study and other sentinel node studies, surgery would generally proceed to complete the full therapeutic groin node dissection. A limited retrospective outcome analysis of conservative node debulking followed by RT compared with full groin dissection in patients with gross nodal metastases152 has shown no obvious differences in the rates of groin relapse or survival. This provides grounds for cautious optimism that limiting groin treatment to removal of only microscopically positive sentinel nodes followed by RT or chemoradiation may provide equivalent control in the affected groin compared with historical results obtained by more comprehensive groin node dissection.

A study by Rob and associates70 is informative for the determination of radiation target volumes and the design of radiation ports for patients with clinically and radiographically negative groins undergoing elective or prophylactic groin irradiation. Four regions were defined: the superficial medial group located above and medial to the femoral vein and medial to the saphenous vein; the superficial intermediate group located in the vicinity of but superior and lateral to the saphenous and femoral veins; the superficial lateral group located in the outer third of the groin; and the profundum nodes located deep and medially along the femoral vein. Of the 118 sentinel lymph nodes found in 82 groins in this study, 84% were in the superficial medial region or in the superficial intermediate region, and 16% were in the profundum group. Importantly, no sentinel lymph nodes were found in the superficial lateral region. Covering only tissues overlying and medial to the femoral vessels allows substantial reduction in radiation dose to the femoral necks and metaphyseal regions while ensuring that first echelon nodes are comprehensively included. Because insufficiency fractures of the femur constitute a rare but serious complication of groin node irradiation, tailored treatment volumes based on understanding of the relative risk of different node groups within the groin may be helpful in reducing the risk of this serious cause of delayed treatment morbidity.

For patients with small lateralized lesions and no involvement of the ipsilateral nodes, the incidence of contralateral groin node involvement is extremely low and routine dissection of the contralateral nodes is omitted.67,90 Bilateral dissections are recommended for patients whose tumors involve or approach within 1 cm of midline structures or involve the anterior labia minora.

When nodal disease is fixed or ulcerating, the local tumor burden is large and unlikely to be controlled by either surgery or irradiation alone. In such patients, combined therapy with chemoradiation and surgery may offer the best chance of local control.153

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy for vulvar cancer was pioneered in Europe in the early 20th century in an era when surgical options for advanced vulvar cancer were limited. As radical surgery became more feasible and surgical results improved owing to improvements in anesthesia, postoperative nutritional support, blood transfusion, antibiotics, and refinements in reconstructive surgery and wound care that evolved in response to the carnage of two world wars, primary RT was largely abandoned. Because of the acute desquamation accompanying radical irradiation of the vulva and the severe late effects of radiation on the vulva in long-term survivors, the use of RT was largely restricted to palliative cases and patients with anatomic extent of disease or medical comorbidities precluding operative intervention.154–157 Radiotherapy equipment and techniques were primitive in comparison to current technology, and radiation fractionation and total dose were naive with respect to potential late normal tissue effects. The perception that RT was a poor second choice as a curative modality stemmed, in part, from the low survival rates reported in early series for patients selected for RT who were unsuitable for primary surgery because of poor general medical condition, advanced disease, or both.

Despite these concerns, the use of irradiation (alone or in concert with concurrent radiopotentiating chemotherapy) in the treatment of vulvar cancer has increased dramatically in the past three decades. Commonly administered as adjuvant therapy before or after conservative surgery, chemoradiation has also emerged as a rational alternative treatment for patients whose extent of disease would require exenterative procedures or other extensively deforming surgical interventions. Two important prospective clinical trials of the GOG (i.e., GOG 37, GOG 101)98,158 helped form the foundation for these changes in management. Additionally, two randomized prospective trials159,160 demonstrated the superiority of chemoradiation to RT alone in the treatment of cancers of the anal canal. Extension of chemoradiation to the treatment of patients with vulvar cancer was a natural extrapolation from encouraging reports of successful treatment of anal canal cancer patients with anatomic and functional preservation of the anorectum.

Adjuvant Postoperative Radiation Therapy

A beneficial role for adjuvant nodal irradiation for involved nodes was established through a GOG randomized trial (GOG 37). This trial compared ipsilateral pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) (node dissection cephalad to the inguinal ligaments, n = 55) to RT (45 to 50 Gy, n = 59) administered to the bilateral groins and pelvis (excluding the tumor bed and residual vulva) in 114 surgically treated patients who were found to have groin node metastasis. Pelvic nodes were involved in 15 of 53 patients (28%) undergoing pelvic lymphadenectomy, 9 of whom died within 1 year. With median follow-up in survivors of 74 months, the OS was 51% in irradiated patients at 6 years compared with 41% in patients treated by PLND. The cancer-related death rate was 51% after PLND, compared with 29% after irradiation (p = .015). Subset analysis in this relatively small trial suggested that the benefit of radiation was confined to patients with gross node metastasis, extracapsular extension, or metastases to two or more nodes. The major effect of RT was a reduction in groin failures; the irradiated patients had a 5% crude incidence of groin relapse compared with 24% after PLND. The tumor bed and residual vulvar tissues were not irradiated, and a 12% crude incidence of vulvar recurrence was observed across both treatment arms.140 Data from two other studies suggest that macroscopic involvement of a single node and extracapsular invasion confer a risk of inguinal recurrence after surgery that is as high as in those with multiple lymph node involvement, suggesting that such patients may also benefit from postoperative irradiation.4,161 However, after therapeutic groin dissection, patients with microscopic intracapsular metastasis to a single groin node do not benefit from the addition of irradiation.2

The target volume for adjuvant postoperative RT will depend on the indications for adjuvant therapy. For patients with negative groin nodes but adverse histopathologic factors discerned on study of the excised primary tumor, focal vulvar irradiation targeted at inadequate margins, residual vulva, and adjacent perineal skin is appropriate, although often it is difficult to define clinically the limits of the surgical bed. For patients with unilateral node metastases in whom the contralateral groin has been dissected and is negative, it may not be necessary to include the contralateral groin and pelvic nodes, although they were treated in the GOG study of adjuvant irradiation.98

Many patients with node involvement will also have indications to treat the primary tumor bed. However, whether to routinely include vulvar irradiation in all patients undergoing adjuvant postoperative nodal radiotherapy remains controversial. Assessment of risk factors associated with the primary tumor may assist in making this decision. Dusenbery and colleagues162 reported 27 patients with squamous carcinoma of the vulva and 1 to 15 (average 4) histologically involved inguinal lymph nodes who were treated after radical surgery. Postoperative RT was directed at the bilateral (19) or unilateral (7) groin and pelvic nodes. Twenty-six patients had the primary tumor bed shielded. Actuarial 5-year OS and disease-free survival (DFS) estimates were 40% and 35%. Relapses developed in 63% (17/27) of the patients at a median of 9 months from surgery (range, 3 months to 6 years). Central recurrences (under the midline block) were present in 13 of these 17 patients (representing 50% of the patients treated with the midline blocked), either as central only (8 patients), central and regional (4 patients), or central and distant (1 patient), leading the authors to conclude that the target volume for adjuvant postoperative RT for patients with node metastases should include the tumor bed.162 There is consensus in patients with pathologically uninvolved margins of less than 5 mm that conservative reexcision (if feasible) or adjuvant RT is indicated. For patients with margins less than 8 mm but more than 5 mm there is cordial disagreement. Depth of invasion more than 5 mm and/or the presence of lymphovascular space invasion may tip the decision in favor of local irradiation because reexcision would not overcome these remaining prognostic factors.

Whether adjuvant local RT can overcome the negative prognostic impact of close or positive margins, capillary lymphatic space involvement, and depth of invasion is unproven. However, suggestive evidence regarding margins is provided by the outcomes observational study of Faul and colleagues.141 Sixty-two patients with invasive vulvar carcinoma and either positive or close (<8 mm) margins of excision were retrospectively studied. Thirty-one patients were treated with adjuvant RT to the vulva, and 31 patients were observed after surgery. Local recurrence occurred in 58% of observed patients and in 16% of patients treated with adjuvant RT. Adjuvant RT appeared to significantly reduce local recurrence rates in both the close margin and positive margin groups. On multivariate analysis, adjuvant RT and margins of excision were significant prognostic predictors for local control. The positive margin observed group had a significantly worse actuarial 5-year survival than the other groups (p = .0016), and adjuvant radiation significantly improved survival for this group. The 2-year actuarial survival after developing local recurrence was only 25%, lower than is often reported for salvage therapy, and local recurrence was a significant predictor for death from vulvar carcinoma (risk ratio 3.54).141

Preoperative Radiation Therapy

In the 1960s, Boronow pioneered the use of preoperative RT followed by more conservative surgery in patients with locally advanced or recurrent vulvovaginal cancers as an alternative to pelvic exenteration. After updating his experience with a total of 48 treated cases (37 primary cases and 11 cases of recurrent disease),163 he reported a 72% 5-year survival for all 48 cases treated. One patient required a total pelvic exenteration for local failure, and one had a posterior exenteration for local failure. One bladder and one rectum were lost to permanent diversion because of radiation injury. Five of 96 viscera (48 urinary bladders and 48 rectums) were lost and 91 (94.8%) were retained. Three small series164–166 totaling 26 patients treated with 30 to 55 Gy of preoperative radiation reported histologically negative surgical specimens in 13 patients (50%) with only microscopic residual disease in others.

Preoperative Chemoradiation

Several single-institution studies reported encouraging results employing preoperative chemoradiation before conservative resection in patients with locally advanced or locally recurrent vulvar cancer.167,168 These reports, along with reported treatment successes using chemoradiation for anal and esophageal cancer, provided much of the foundation for protocol work beginning in 1989 in the GOG.

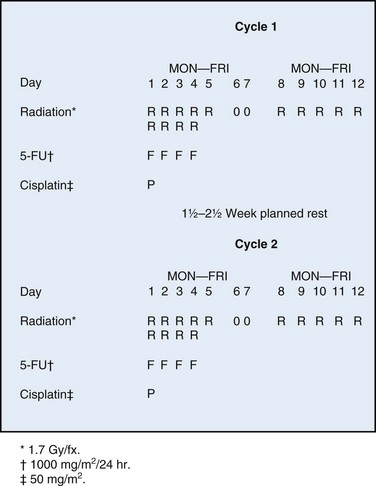

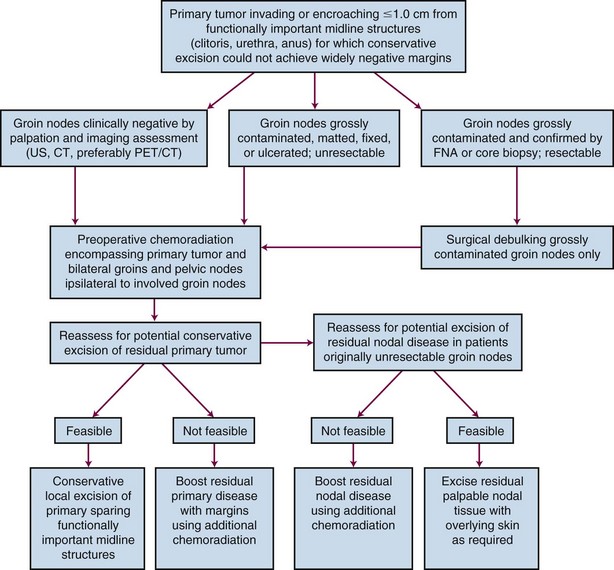

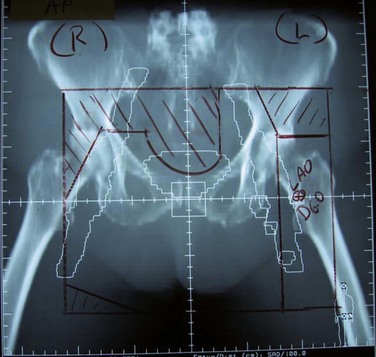

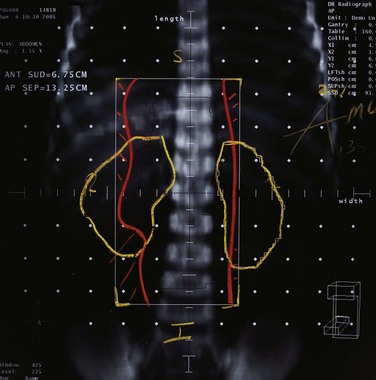

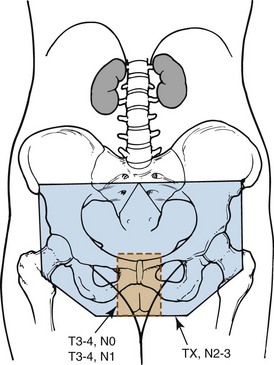

GOG protocol 101 utilized preoperative chemoradiation consisting of 47.6 Gy in once- or twice-daily fractions of 1.7 Gy synchronously with two courses of infusional 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and cisplatin as initial therapy for 73 patients with extensive squamous cancer of the vulva (1969 FIGO stages III and IVA, American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC] 1969 T3/T4, N0/N1), followed by surgical excision of residual primary tumor plus bilateral inguinofemoral lymph node dissection.158 The dose-fractionation schedule for chemoirradiation employed in GOG 101 is schematically depicted in Figure 58-5, and the target volume irradiated is shown in Figure 58-6. The planned 1.5- to 2.5-week treatment interruption was intended to mitigate the severity of acute radiation dermatitis that can progress to confluent moist desquamation, as well as to permit hematologic recovery. Twice-daily irradiation was employed to optimize the radiation drug synergism. Seven patients did not undergo a post-treatment surgical procedure because of deteriorating medical condition (2 patients); other medical condition (1 patient); unresectable residual tumor (2 patients); and patient refusal (2 patients). After chemoradiation, 33 of 71 (46.5%) patients had no visible vulvar cancer at the time of planned surgery; in the 31 of 33 who proceeded to surgical resection, a pathologic complete response was found in 22 (70%). Of the 38 patients who had gross residual cancer before surgery (53.5%), 5 had positive resection margins and 4 of 5 had either further RT to the vulva (3 patients) or wide local excision and vaginectomy (1 patient). Only 2 of 71 patients (2.8%) ultimately had residual unresectable disease. Urinary or fecal continence was not preserved in only 3 patients. The authors158 concluded that preoperative chemoradiation is feasible and may reduce the need for more radical surgery, including primary pelvic exenteration.

Figure 58-6 Volumes irradiated in GOG protocol 101.158 Small rectangular volume (dashed lines) was irradiated in patients with AJCC 1969 T3-4, N0-1 disease with clinically uninvolved groin nodes. Larger volume (solid lines) was irradiated in patients with grossly involved groin nodes (AJCC 1969 TX, N2-3).

Adapted from Moore DH, Thomas GM, Montana GS, et al: Preoperative chemoradiation for advanced vulvar cancer. A phase II study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 42:79-85, 1998.

In parallel with the study of preoperative chemoradiation for patients with locally advanced primary vulvar cancer, the GOG studied patients presenting with advanced disease in the inguinofemoral nodes (1969 nodal classification N2/N3), including some patients with matted, fixed, or ulcerated groin nodes not judged resectable by initial surgery.153 The identical preoperative chemoradiation schedule was employed to treat 46 patients except the treatment volume was increased to encompass the groins and caudal pelvic nodes as depicted in Figure 58-6. Three patients died during treatment, and 1 refused to complete the therapy. Four patients who completed chemoradiation did not undergo planned surgery—2 patients dying of non–cancer-related causes and 2 patients with disease that remained unresectable. After preoperative chemoradiation, the disease in the lymph nodes was judged resectable in 38 of 40 patients. Two patients who completed chemoradiation did not undergo surgery because of pulmonary metastasis. One underwent radical vulvectomy and unilateral node dissection and the other had only radical vulvectomy. The operative lymph node specimen was histologically negative in 15 of 37 patients. Nineteen patients developed recurrent and/or metastatic disease. Local control of the disease in the lymph nodes was achieved in 36 of 37 and in the primary area in 29 of 38 patients. Two patients died of treatment-related complications. The authors153 concluded that resectability and local control of advanced nodal disease may be obtained with a high probability after preoperative chemoradiation in patients with carcinoma of the vulva with extensive groin adenopathy.

Acute toxicity in GOG 101 was primarily in the irradiated skin, with moist desquamation reported in “many” patients, although this was probably underreported. Major hematologic toxicity was rare. When initial radiation target volume includes the groins and pelvic nodes (see Fig. 58-6) because of confirmed node metastasis, hematologic and gastrointestinal toxicities can be expected to be significantly more severe.

Preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy (without irradiation) has been used in the treatment of locally advanced vulvar cancer.169–171 Response rates have been quite variable; and although complete clinical or pathologic responses have been recorded,170,171 these are very rare. This approach has not gained broad acceptance, because response to combined chemoradiation is more reliable and predictable.

Primary Radiation or Chemoradiation

Treatment of Primary Lesions

Whether RT, in higher dose than employed preoperatively, alone or combined with concurrent chemotherapy, can or will replace radical surgery as treatment for vulvar cancer is unknown. Reports of radiotherapy using contemporary techniques and dose-fractionation schedules used as monotherapy after biopsy are uncommon. Owing to probable selection biases in choosing patients for such treatment, it is impossible to meaningfully compare outcomes to alternative treatment strategies. It only can be concluded that a significant proportion of patients may be considered cured when managed in this fashion.172,173

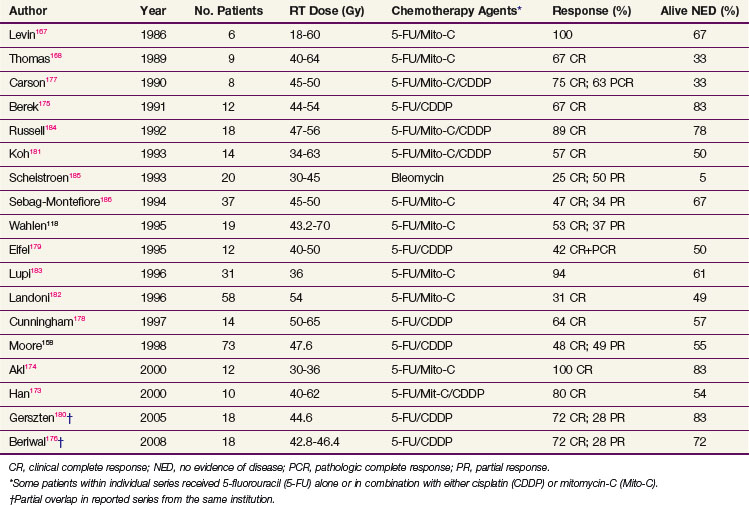

Increasingly, the trend is to employ definitive chemoradiation (irradiation and synchronous radiopotentiating chemotherapy) for disease judged to be too extensive for functionally conservative surgery or for small lesions that are critically located in proximity to important midline structures. Reports of response rates for initial chemoradiation used either preoperatively or as definitive therapy* are tabulated in Table 58-6.

Unfortunately, the heterogeneity of the small numbers of patients selected for this approach, using variable selection criteria, the drugs employed, the radiation doses utilized, and the duration of follow-up are so diverse as to defy identification of an optimal regimen. However, as experience continues to accumulate and observational data become more mature, it seems probable that definitive chemoradiation will emerge as a viable treatment plan for patients whose disease is unresectable by virtue of its extent or who are medically inoperable due to comorbidities. The majority of series have employed 5-FU–based regimens, often with cisplatin or mitomycin-C as second agents.†

In a nonrandomized, retrospective outcomes comparison of two different chemoradiation approaches used contemporaneously in the treatment of 44 patients with advanced vulvar cancers at two Harvard Medical School–affiliated radiation oncology departments in Boston (Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Dana-Farber Cancer Center)191 there were no clear differences in the apparent efficacy of treatments based on 5-FU (n = 28), with or without cisplatin or mitomycin (similar to GOG 101), and treatments based on weekly cisplatin alone (n = 16).

Treatment of Inguinal Nodes

A randomized study conducted by the GOG192 compared primary inguinal dissection with primary groin irradiation to control the inguinofemoral nodes in conjunction with radical vulvectomy in patients with T1/T2 squamous cancer of the vulva and clinically nonsuspicious groins. This study was terminated before completion of accrual when interim monitoring revealed an excess of nodal relapse and death among patients treated with nodal irradiation. Radiation therapy consisted of 50 Gy in daily 2-Gy fractions administered to a depth of 3 cm below the anterior skin surface. On the groin dissection trial arm there were 5 of 25 (20.0%) patients with positive groin nodes. Those node-positive patients received postoperative irradiation. There were five groin relapses among the 27 (18.5%) patients randomized to receive the groin radiation regimen and none among patients treated with initial groin dissection. Patients who had initial groin dissection had significantly better progression-free interval (p = .03) and survival (p = .04). Although resistance of the inguinal node metastases to radiation is one possible reason for the unacceptable groin failures after RT alone, a subsequent analysis of that study indicated that the groin radiation technique employed was inadequate to encompass the nodal bed with the prescribed tumor dose,132 because it was assumed that the inguinal lymph nodes lay 3 to 4 cm below the surface. It was subsequently illustrated that the median depth of lymph nodes in the groin was 6 cm from the surface but could be as deep as 17 cm in large patients. Kalidas133 obtained measurements of the inguinal node depths of 31 patients with cervical, vaginal, or vulvar malignancies from planning CT scans. Twenty-four of 81 superficial inguinal node depth measurements were greater than 3 cm, and all of 84 deep inguinal (femoral) node measurements were beyond the 3-cm range. In planning radiation-based therapy to the groins there can be no substitute for direct measurement of groin node depth, by CT or ultrasonography. Depth of the deep femoral lymphatics, for radiation prescription purposes, is now usually specified as the depth of the femoral artery as it passes beneath the inguinal ligament.

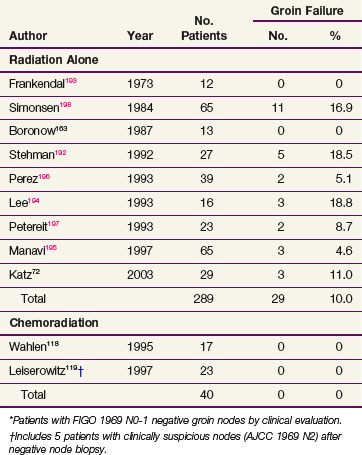

A review of primarily observational studies72,163,192,193–198 indicates that the risk of groin node failure after irradiation in patients with clinically negative groin nodes is approximately 10% (Table 58-7). These studies did not always report the expected incidence of nodal disease in the patients irradiated, so the efficacy of RT is uncertain. However, approximately 20% of patients with clinically nonsuspicious groin nodes are expected to have subclinical metastases if elective nodal dissection is performed (see Table 58-1).

TABLE 58-7 Results of Elective Groin Radiation Therapy or Chemoradiation in Patients with Vulvar Cancer and Clinically Negative Inguinofemoral Lymph Nodes*

Two articles provide indirect evidence that RT without surgery can eradicate microscopic disease in clinically negative groin nodes in some patients. Frankendal and associates193 performed radical vulvectomy without inguinal node dissection in 29 patients with clinically negative groin nodes. Twelve patients received elective inguinal nodal irradiation; the radiation dose ranged from 30 to 60 Gy in 15 to 55 days. There were no nodal recurrences. Seventeen patients received no irradiation, and 3 experienced inguinal failure. Manavi and colleagues195 reported on 135 patients who underwent simple vulvectomy for T1 cancers without groin dissection. Sixty-five patients underwent elective groin irradiation. Those patients had, on average, less favorable primary tumors than the 70 patients who had no treatment to their groins. There were three groin recurrences in the irradiated patients (4.6%) and seven groin recurrences in the unirradiated patients (10%).

Two observational studies totaling 40 patients reported the outcome for patients treated for locally advanced vulvar cancer with chemoradiation that included elective treatment of undissected groin nodes. There were no groin relapses.118,119

Treatment Algorithms and Approaches

Early, Favorable or Low-Risk Disease

A practical definition of early, favorable (low risk) disease is disease that can be reasonably expected to be curatively managed by conservative surgery alone. The extent and location of the primary tumor are amenable to radical excision without sacrificing the function of the urethra, the anorectum, the clitoris, and vagina. Generally this will include patients without palpable or imaging evidence of inguinal node metastasis. For low-risk cancers that are unifocal and well lateralized, radical wide local excision of the primary lesion in the vulva is recommended for most patients. The reported results from observational studies of radical wide local excision for T1 or T2 tumors suggest an average survival rate of approximately 90%. The criteria proposed for the selection of patients for such conservative surgical resection vary but in general include patients with tumors less than 2 cm in diameter and depth of invasion less than 5 mm.71,90,92,139,199

Although wider excision, if feasible, may for some patients eliminate the risk of close margins, it may not be feasible or advisable for medial or deep margins and will not overcome other risk factors. One retrospective series of 62 patients with positive or close (<8 mm) margins showed, on multivariate analysis, that adjuvant irradiation significantly reduced local recurrence rates and significantly improved survival rates for the positive margin group.141 The role of adjuvant RT after radical wide local excision of vulvar cancer was being explored in a Gynecology Oncology Group randomized clinical trial, but the trial had to be abandoned because of lack of accrual.

Historically, standard management of the inguinal regions for all patients with invasive disease of larger than 2 cm or greater than 1 mm depth of invasion (FIGO stage IA) has been groin dissection. Results from the GROINSS-V study suggest that in selected patients with unifocal primary tumors less than 4 cm without encroachment on the urethra, vagina, or anus and with successful retrieval of sentinel node(s) that are negative by pathologic ultrastaging, the acute and chronic morbidities of groin dissection may be avoided. The risk of subsequent groin relapse is low, and, with careful observation, isolated node recurrence may rarely (anecdotally) be salvaged by secondary treatment of an undissected groin. However, the majority of patients with relapse of the disease in the groin will die of vulvar cancer.* If this approach is adopted, pretreatment nodal assessment by CT, MRI, or ultrasonography should be performed to exclude the presence of bulky metastatic nodes and minimize the risk of false-negative sentinel node studies.

Postoperative RT to the inguinal and pelvic nodes is recommended for patients with involvement of two or more nodes and for those with a single node with macroscopic metastasis (>3 mm) or extranodal extension. In patients with diagnostic imaging (preferably PET/CT) that shows no evidence of pelvic adenopathy, the superior border of the treatment volume should probably extend no more cephalad than the inferior or middle of the sacroiliac joints in order to limit acute and chronic enteric morbidity. The randomized study from which these recommendations are largely drawn (GOG 37) administered adjuvant radiation to both groins even when involvement was unilateral.98 The benefit of adjuvant RT to the contralateral negative groin is uncertain, and treatment of that volume may be unnecessary. Two issues remain controversial. Whether residual vulva and tumor bed should routinely be included in the treatment volume when groins and pelvic nodes require irradiation remains unclear, although histopathologic features associated with the primary tumor may suggest that this is prudent in many if not all patients. Whether concurrent chemotherapy should be administered with purely adjuvant treatment to further enhance the regional efficacy of irradiation is also the substance of conjecture and debate. Hypothetically, the increase in acute toxicity could be offset by improved regional control, possibly with a reduced dose of irradiation that might translate into diminished late radiation effects. This hypothesis remains untested. Algorithms for management of patients with early, lateralized disease found in Figure 58-3 and Figure 58-7 are premised on the presence of a team skilled in the performance of sentinel node biopsies or the availability of PET/CT. Absent either capability, radical wide local excision and at least ipsilateral inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy is recommended. Predicated on histopathologic findings from study of the excised groin nodes and the primary tumor, subsequent management is suggested by the algorithms in Figures 58-7 and 58-8.

Small Primary Tumors Encroaching on Midline Structures

Although surgical excision remains the historical standard treatment for patients with small, midline primary tumors, it is not unreasonable to consider treating a primary midline lesion, regardless of size, with a localized field of primary irradiation or chemoradiation if surgical excision would result in predictable loss of cosmesis or function. Although such patients can be cured with surgery as monotherapy, the functional and cosmetic impairments can be psychologically devastating. In many patients, clinical shrinkage after a modest dose (45 to 54 Gy) of irradiation or chemoradiation will permit conservative excision of residual tumor with excellent preservation of function and cosmesis (Fig. 58-9).

Locally Advanced Disease and Palliation

Historically, adequate surgical clearance of large primary tumors that involve the anus, rectum, vagina, rectovaginal septum, or proximal urethra would usually include radical vulvectomy plus some type of pelvic exenteration. Five-year survival rates with primary surgery for locally advanced disease range up to 50%.201 However, physical and psychological morbidity from such surgical procedures is high.

Boronow and colleagues,163 in a landmark study, explored the use of preoperative irradiation in locally advanced disease with the intent to reduce the scope of subsequent surgery. Thirty-seven patients with locally advanced vulvar cancer were treated with variable doses of radiation (median, 48 Gy) followed by surgery. The 5-year survival rate was 75.6%. Approximately 40% of patients had no residual disease in the operative specimen after preoperative irradiation.

Subsequently, multiple investigators reported favorable results with preoperative chemoradiation for selected patients with locally advanced disease treated with the intent of permitting subsequent nonexenterative surgery (see Table 58-6). Consequent to these studies as well as the results of GOG 101 there is a growing acceptance by gynecologic oncologists that concurrent chemotherapy and RT constitute the initial treatment of choice for primary management of patients with locally advanced disease.

Randomized trials for vulvar cancer have not been performed to test whether concurrent chemotherapy confers additional benefit to irradiation alone. The drug regimens commonly used include 5-FU, alone or in combination with cisplatin or mitomycin-C, or weekly cisplatin alone (GOG 205).* Results with bleomycin have been found unsatisfactory either owing to gross tumor persistence or to a high local relapse rate after initial favorable response.185,188 Information from prospective controlled trials of chemoradiation (RT alone compared with RT with concurrent 5-FU and mitomycin-C) for cancers of the anal canal suggests that the addition of chemotherapy is useful and may permit some reduction in the total radiation dose necessary to eradicate disease.159,160 An algorithm for the management of patients with locally advanced primary cancer, with or without locally extensive groin metastases, is shown in Figure 58-10.

Locally Advanced Nodal Disease

Patients with initially bulky resectable involved nodes may undergo either initial surgical removal of the bulky nodes followed by postoperative RT or chemoradiation or initial RT or chemoradiation followed by operative removal of any residuum. The optimal sequencing of therapies remains controversial, because surgery will delay initiation of RT and because preoperative irradiation may compromise wound healing. Commonly, patients with bulky inguinal nodes will also have locally advanced primary tumors, in which case initial RT or chemoradiation is a logical sequence choice. Conversely, initial gross adenopathy may be difficult to reliably identify and excise after preoperative chemoradiation, and a good case can be made for initial surgical removal as depicted in the algorithm in Figure 58-10. If there is clinical uncertainty whether all gross adenopathy can be removed from the groins, imaging with ultrasonography, CT, or MRI may aid in elucidating the spatial relationships between blood vessels, nerves, bone, and metastatic adenopathy. These imaging modalities may be particularly useful in defining disease extent in large patients.

Regardless of the sequencing of therapies, groin surgery should be limited to removal of gross adenopathy rather than an en bloc removal of all groin lymphatic tissue. It should be accomplished through the smallest feasible incision to accomplish this objective. The intent of such surgery is to reduce groin cancer volume to a microscopic, occult burden that can be controlled by modest doses of fractionated radiation. Conversely, radiation dose administered either before or after surgical cytoreduction should generally be restricted to an effective dose for controlling microscopic or occult disease. By limiting the extent of groin dissection in anticipation of subsequent radiation, and by limiting radiation dose in anticipation of surgical removal of residual, bulky disease, some acute complications (wound dehiscence, infection) and late sequelae (lymphedema, femoral fracture, arterial occlusion) might be reduced in severity or avoided altogether. One retrospective series describing outcomes after debulking groin surgery and radiation compared with complete groin dissection and RT reported no difference in groin recurrence-free survival or OS.152

Locally Recurrent or Metastatic Cancer

The outcome for patients who experience relapse of vulvar cancer after primary therapy is markedly dependent on the site of relapse. Although salvage rates for isolated vulvar recurrences are substantial, relapses in groins or pelvic nodes or hematogenous metastases are almost uniformly fatal, regardless of salvage modalities employed. For patients with distant metastases, systemic chemotherapy with agents active against squamous cancer is often offered but response rates are disappointing and response durations are generally measurable in a few months.111,202–211

Agents that may be useful when given concurrently with radiation (5-FU, cisplatin, mitomycin-C) have limited efficacy when given alone. Inferential evidence for this statement includes patients with regionally extensive vulvar cancer treated by irradiation and synchronous cytotoxic chemotherapy who manifest prompt and marked response within the irradiated volume while simultaneously developing overt metastatic disease outside the irradiated volume. An example is illustrated in Figure 58-11.

Inguinal recurrences may be amenable to palliative management with irradiation or chemoradiation to provide local control. Few patients, however, survive long term.73,111,112,146,147

Local vulvar recurrence appears to be related to the previously described risk factors and, in particular, to surgical resections with margins less than 8 mm pathologically (in formalin-fixed tissue). Several reports have suggested that up to 75% of patients with vulvar recurrence of cancer may be cured, usually when treated with surgical re-excision.73,212 Boronow and colleagues163 reported a 5-year OS of 63% with modest dose radiation. However, Faul and associates141 reported only a 25% 2-year actuarial survival after vulvar recurrence. Radiation therapy or chemoradiation for local recurrence is an option, particularly when the lesion is not amenable to repeat resection without predictably inadequate surgical margins or compromise of functionally important midline structures.168,184

Irradiation Techniques and TOLERANCE

Groin and Nodal Irradiation

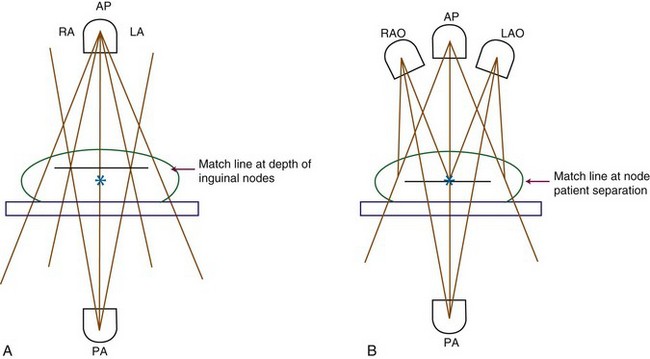

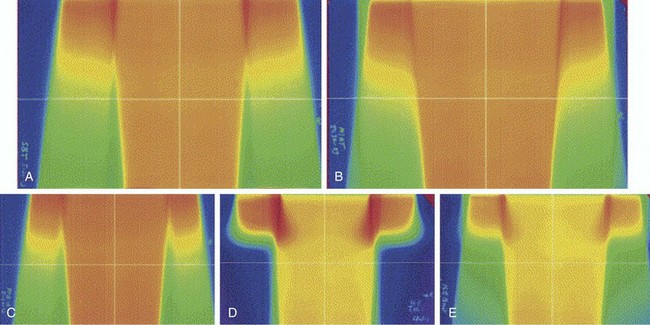

GOG protocol 37,98 which established the usefulness of postoperative adjuvant groin and pelvic irradiation in patients with metastases to inguinofemoral nodes, used external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) bilaterally to the inguinal and femoral dissection beds and pelvic nodes even when node involvement was unilateral. The specific radiation doses in the study (45 to 50 Gy in 1.8- to 2.0-Gy fractions) are in the range commonly prescribed to control occult microscopic disease. The technique utilized an anterior and posterior parallel, opposed pair of fields. The inferior border of the volume recommended was determined clinically using a margin lying parallel and 6 to 8 cm inferior to the inguinal skin crease or ligament. The GOG study used a superior border somewhat arbitrarily placed at the L5-S1 interspace, although the value of extending the field to this level superiorly is uncertain because the observed survival gains appear to be related to improved control of the inguinal regions and not to improved control of the pelvic nodes.140 Treating this volume with this technique necessarily will limit the radiation dose to 45 to 50 Gy because of normal tissue dose limitations (bowel, femoral necks, pelvic girdle).

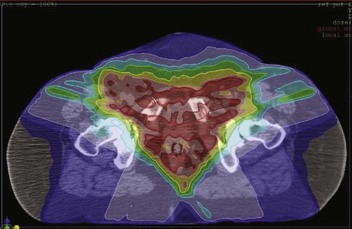

For patients receiving nodal irradiation only, with no indications for vulvar irradiation, midline structures may be spared superfluous treatment. It is important to confirm clinically that the lateral margins of the excluded central tissue do not encroach on the medial aspects of the inguinal node bed and obturator nodes, resulting in underdosage. In general, the shielded midline tissue should be no wider than the distance between the pubic tubercles, because it is intended only to reduce the dose to the distal urethra, vagina, and anorectum and residual vulva. Use of a midline block has been reported to be associated with a high risk of local recurrence in the shielded midline. In a series of 26 patients administered radiation postoperatively for positive groin nodes who had midline shielding, 13 patients (50%) had local recurrence.162 A midline block or other techniques to exclude midline structures should be used only if risk factors for local recurrence are minimal.