Chapter 70 Neuroblastoma

Etiology and Epidemiology

Neuroblastoma accounts for 8% to 10% of all childhood cancers, with approximately 650 cases diagnosed annually in the United States.1 It is the most common extracranial solid tumor in children and the most common malignancy of infants. The median age at diagnosis is 17 months, and the male-to-female ratio is 1.1 : 1. Forty percent of patients are diagnosed when younger than 1 year of age, 89% are younger than 5 years of age, and 98% are younger than 10 years of age.2

Most primary neuroblastoma tumors occur in an anatomic distribution that is consistent with the location of neural crest tissue because the tumor arises from primitive adrenergic neuroblasts. The adrenal gland is the most common primary tumor site, accounting for 35% of cases overall. However, children younger than 1 year of age have a tumor arising from the adrenal gland in only 25% of cases. Other common sites include the low thoracic and abdominal paraspinal ganglia (30%) and posterior mediastinum (19%). Ganglia in the pelvic and cervical regions account for 2% to 3% of tumors, and in 1% a primary site is never known.3

Prevention and Early Detection

Because neuroblastomas frequently produce high levels of catecholamines, which can be detected in the urine, mass screening for the disease in infants has been studied in a number of countries. Extensive trials in numerous countries have shown that tumors detected by screening tend to be extremely favorable. Unfortunately, screening has not had an impact on survival or early detection of high-risk neuroblastoma.4

The development and subsequent regression of clusters of neuroblastoma is a normal embryologic event, and the development of clinically detectable neuroblastoma appears to be a consequence of disruption of this process. Microscopic neuroblastoma-like nodules frequently can be found at autopsy in infants who die of unrelated causes.5 Furthermore, clusters of cells consistent with neuroblastoma occur uniformly in the adrenal glands of all fetuses, peaking at between 17 and 20 weeks of gestation, and then spontaneously regress by birth or in early infancy.6

The cause of neuroblastoma is not known in most cases. Prenatal or postnatal exposure to drugs, chemicals, or radiation has never been proven to be associated with an increased incidence of the disease.2 A small fraction of neuroblastomas are considered familial and are associated with a germline mutation. At least 20% of patients with familial neuroblastoma have bilateral or multifocal disease, which tends to present at an earlier age.7

Biologic Characteristics and Molecular Biology

Specific molecular characteristics of neuroblastoma have been well described and have a significant influence on prognosis and selection of therapy. Two of the most notable alterations are deletion of the short arm of chromosome 1 (1p) and MYCN (also known as N-myc) amplification. The former is thought to result in the loss of a tumor suppressor gene on 1p, whereas MYCN is a proto-oncogene found on the distal short arm of chromosome 2. There is a strong correlation between these genetic events, and both are found more commonly in advanced disease and are associated with a significantly worse prognosis.8 MYCN amplification occurs in 25% of primary neuroblastomas overall but in only 5% to 10% in patients with low-stage and stage 4S disease and 30% to 40% in patients with advanced disease.9

Chromosomal ploidy or DNA index (DI) is another significant marker of prognosis that is particularly useful in infants younger than 18 months of age. Near-diploid or pseudo-diploid tumors have near-normal nuclear DNA content but often have structural chromosomal abnormalities, including MYCN amplification. Hyperdiploid or near-triploid tumors typically lack MYCN amplification and 1p deletion and are more likely to have a favorable outcome.10

Pathology and Pathways of Spread

Neuroblastoma is one of many small, round, blue cell tumors of childhood, but it can be distinguished by staining for neuron-specific enolase, synaptophysin, and neurofilament. Electron microscopy can also be used and typically reveals neurosecretory granules that contain catecholamines, microfilaments, and parallel arrays of microtubules within the neuropil.11 The characteristic histologic appearance is that of small, uniform cells containing dense, hyperchromatic nuclei and scant cytoplasm with neuropil. Homer-Wright pseudorosettes representing neuroblasts surrounding areas of eosinophilic neuropil are seen in up to 50% of cases.

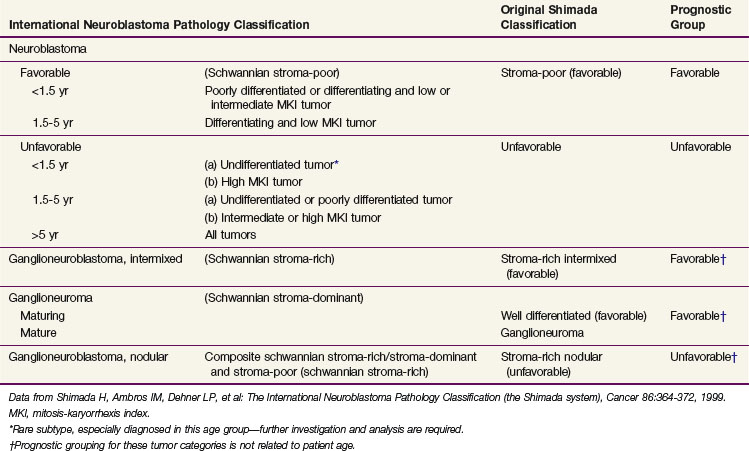

A variety of different classification systems have been used to help define the prognosis for neuroblastoma. The International Neuroblastoma Pathology Committee (INPC) system is the most widely used and validated. Characteristics of this system are listed in Table 70-1. This represents a modification of the Shimada system that classifies tumors according to the degree of differentiation toward ganglion cells, amount of Schwann cell stroma present, whether the tumor is nodular, degree of calcification, and the mitotic-karyorrhexis index.

TABLE 70-1 Prognostic Evaluation of Neuroblastic Tumors According to the International Neuroblastoma Pathology Classification (Shimada System)

Neuroblastoma commonly spreads via lymphatics to regional lymph nodes, often in the para-aortic chain, and less commonly to the next echelon of lymphatics, such as the left supraclavicular fossa (Virchow node) in patients with abdominal tumors. Hematogenous spread often occurs to bone marrow, bone, and liver. Neuroblastoma appears to have a proclivity for the bones of the skull and especially the posterior orbit, which can cause the clinical presentation of “raccoon eyes” from periorbital ecchymosis. Lung and brain metastases are rare at presentation. However, with improvements in systemic therapy, isolated parenchymal brain metastases are now occurring with a relatively high incidence in high-risk patients after apparent disease remission. These central nervous system relapses require craniospinal radiation therapy (RT) because of a high risk of leptomeningeal dissemination.12

Clinical Manifestations, Patient Evaluation, and Staging

A plain radiograph of the chest or abdomen may show a soft tissue mass representing the primary tumor, and calcifications are present in 85% of tumors. Staging of neuroblastoma requires numerous imaging modalities. The primary tumor and regional lymph nodes should be imaged with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging.13,14 These studies should also be used to assess for metastases in the liver as well as spinal extension and resectability of the primary tumor. They also may be used to clarify the extent of bone metastases in specific locations, such as the skull.

Bone metastases may be determined with technetium-99m (99mTc)–labeled bone scintigraphy, with metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy, and/or with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-labeled positron emission tomography (FDG-PET). For high-risk patients, it may be worthwhile to perform all three studies because different forms of imaging may be more useful than others for different patients. MIBG is a sensitive and specific method (close to 90%) to assess the primary tumor and metastatic disease. A 99mTc bone scintiscan is typically used for detection of bone metastases even if MIBG studies are used.15,16 Studies regarding the utility of FDG-PET for neuroblastoma are ongoing. Complete staging includes two bilateral posterior iliac crest bone marrow aspirates and biopsies. A single positive result is sufficient for the documentation of bone marrow involvement.17

Because excess catecholamines are produced in most cases, urine catecholamines and their metabolites, specifically norepinephrine, vanillylmandelic acid, 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol, and/or homovanillic acid are typically measured. Urinary levels of catecholamines are often given as ratios to the urinary creatinine value.18

Previous staging systems including the Evans and D’Angio classification,19 historically used by the Children’s Cancer Group, and a system formerly used by the Pediatric Oncology Group20,21 have been replaced by the International Neuroblastoma Staging System (INSS) as the standard staging system (Table 70-2). To interpret the literature, it is necessary to make comparisons between the INSS and the two other staging systems, because differences can be significant. INSS stage 1 is similar to stages I and A. Stage 4 is essentially the same as stages IV and D, and stage 4S is the same as IVS and D-S. The greatest differences are in the middle stages (II and III; B and C). In the INSS system, stage 2 is divided into 2A (incompletely excised tumor) and 2B (ipsilateral lymph node involvement). The INSS has also formalized definitions of response to treatment in an attempt to facilitate cross-study comparisons.17

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Localized tumor with complete gross excision, with or without microscopic residual disease; representative ipsilateral lymph nodes negative for tumor (nodes adherent to and removed with the primary tumor may be positive). |

| 2A | Localized tumor with incomplete gross excision; representative nonadherent lymph nodes negative for tumor microscopically. |

| 2B | Localized tumor with or without complete gross excision, with ipsilateral, nonadherent lymph nodes positive for tumor. Enlarged contralateral lymph nodes must be negative microscopically. |

| 3 | Unresectable unilateral tumor infiltrating across the midline,* with or without regional lymph node involvement; or localized unilateral tumor with contralateral regional lymph node involvement; or midline tumor with bilateral extension by infiltration (unresectable) or by lymph node involvement. |

| 4 | Any primary tumor with dissemination to distant lymph nodes, bone, bone marrow, liver, skin, and/or other organs (except as defined in stage 4S). |

| 4S | Localized primary tumor (as defined for stage 1, 2A, or 2B), with dissemination limited to skin, liver, and/or bone marrow† (limited to infants <1 year of age). |

* The midline is defined as the vertebral column. Tumors originating on one side and crossing the midline must infiltrate to or beyond the opposite side of the vertebral column.

† Marrow involvement in stage 4S should be minimal, that is, less than 10% of total nucleated cells identified as malignant on bone marrow biopsy or on marrow aspirate. More extensive marrow involvement would be considered to be stage 4. The MIBG scan (if performed) should be negative in the marrow.

Data from Brodeur GM, Seeger RC, Barrett A, et al: International criteria for diagnosis, staging and response to treatment in patients with neuroblastoma, J Clin Oncol 6:1874-1881, 1988; and Brodeur GM, Pritchard J, Berthold F, et al: Revisions in the international criteria neuroblastoma diagnosis, staging and response to treatment, J Clin Oncol 11:1466-1477, 1993.

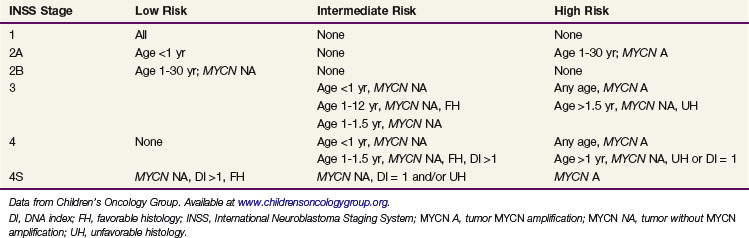

Current protocols for neuroblastoma are based on risk stratification. The proposed risk groups based on clinical and biologic features are outlined in Table 70-3. Survival varies from 85% to 99% for low-risk patients to 20% to 40% for high-risk patients. Disease stage and patient age at diagnosis, as well as biologic characteristics (MYCN, ploidy), have major prognostic significance. The International Neuroblastoma Pathology Classification, based on the original Shimada system, is likely to become the new international standard.

Primary Therapy

The therapeutic approach for neuroblastoma varies tremendously, depending on risk group stratification. The available treatment modalities include surgery, chemotherapy, RT, and a number of newer treatments such as immunotherapy. The following is a discussion of therapy for low-, intermediate-, and high-risk disease, with an emphasis on the role of RT. A basic treatment algorithm for each risk group is shown in Figure 70-1.

Figure 70-1 Treatment algorithm for low-risk (A), intermediate-risk (B), and high-risk (C) neuroblastoma.

Low-Risk Neuroblastoma

Patients with low-risk neuroblastoma (see Table 70-3) can often be cured with surgery alone, even when only a partial resection is obtained. Adjuvant RT was used in the past for incompletely resected tumors but has been shown to be unnecessary. Chemotherapy and RT are now reserved for progressive or recurrent disease. The Children’s Cancer Group recently reported on the outcome of Evans stage I to II neuroblastoma treated with surgery as primary therapy. Event-free survival and overall survival for all patients with stage I disease were 93% and 99%, respectively, and for patients with stage II disease they were 81% and 98%, respectively. Additional therapy (RT, surgery, and/or chemotherapy) was needed in only 10% of patients with stage 1 disease and 20% of patients with stage 2 disease.22 MYCN amplification is rare in low-risk neuroblastoma and has not been shown to convey a worse prognosis in this group.23 In the current Children’s Oncology Group protocol for low-risk neuroblastoma (#P9641), a dose of 21 Gy is recommended for patients with stage 1 and 2 disease who require RT.

Most patients with stage 4S neuroblastoma are in the low-risk category. In spite of having disseminated disease on presentation (as defined in Table 70-2), spontaneous regression occurs frequently and overall survival is excellent.24 However, infants with rapidly progressive disease can suffer fatal respiratory compromise or bowel ischemia caused by severe hepatomegaly. Low-dose irradiation should be immediately considered for such patients. Treatment can be given efficiently, because simulation and anesthesia are not necessary; the liver generally fills the entire abdomen and can be seen on a port film, and the patients are young enough to be immobilized in a papoose. The typical fractionation schedule in this setting is 1.5 Gy for three fractions, which usually leads to rapid relief of symptoms. The risk of long-term harm to the child from radiation exposure is very small because of the low dose.

Intermediate-Risk Neuroblastoma

The current treatment approach for intermediate-risk disease (see Table 70-3) consists of surgery for the primary tumor as well as standard-dose, multiple-agent chemotherapy for 4 to 8 months. An initial biopsy is always performed to obtain a diagnosis and to analyze biologic features. Definitive surgery may be delayed until after chemotherapy, which often makes the tumor more easily resectable. The survival rate for patients with intermediate-risk disease has been reported to be 75% to 98%.

Older studies that addressed the use of radiation for intermediate-risk disease have used a variety of outdated staging systems that make interpretation of the data very difficult. Analysis of Children’s Cancer Group data for stage 2 disease showed a 6-year survival of 98% for those treated initially with surgery alone compared with 95% for those receiving RT and/or chemotherapy.25 Therefore, intermediate-risk patients with stage 2 disease do not require RT as part of their initial treatment.

For patients with stage 3 intermediate-risk neuroblastoma, the older literature supported the use of RT.26 However, because of changes in the staging system with incorporation of biologic features as well as more sensitive diagnostic tools and more intensive chemotherapy, these findings may not be applicable to current management. Patients with stage 3 disease with favorable biology who are treated with surgery and chemotherapy alone have excellent outcomes.

High-Risk Neuroblastoma

Although survival rates have improved for high-risk neuroblastoma with increasingly intensive therapy, considerable progress is still needed. Children older than 1 year of age with stage 4 disease who were enrolled in Children’s Cancer Group studies from 1978 to 1985 had a 4-year survival of 9% compared with 30% for patients treated from 1991 to 1995.27 This group completed a phase III trial that demonstrated that high-dose chemotherapy and RT followed by transplantation of autologous bone marrow is superior to conventional chemotherapy as consolidation in children with high-risk neuroblastoma with 3-year event-free survivals of 34% and 22%, respectively. In the same study, 3-year event-free survival for patients randomized to receive 13-cis-retinoic acid at the completion of cytotoxic therapy was 46% compared with 29% for those who received no further therapy.28

The current therapeutic approach for high-risk disease includes intensive induction chemotherapy, surgical resection of the primary tumor, and possible myeloablative consolidation therapy with stem cell rescue, followed by targeted therapy for residual disease. Patients who have a complete or very good partial response to induction chemotherapy have a better prognosis.29

Evidence for the benefit of primary site RT comes from single-institution trials such as those at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, where a total dose of 21 Gy is given in twice-daily 1.5-Gy fractions. Among 99 patients treated with irradiation to the primary site, the local failure rate was 10%.30 Only 7 of these patients had disease at the primary site at the time of irradiation, and 3 of these had local recurrence, suggesting that 21 Gy is not an adequate dose for gross residual disease.

In spite of an improved outcome for patients with high-risk neuroblastoma who were treated with autologous transplantation, including 10 Gy of total-body irradiation, on the randomized Children’s Cancer Group study 3891, local failure was a major component of unsuccessful treatment. The 5-year locoregional recurrence rate was 51% for patients who received continuation chemotherapy compared with 33% for patients who received transplantation. Patients with residual tumor at the primary site after chemotherapy and surgery received 10 Gy of local RT, whether or not they were randomized to receive total-body irradiation.28

Haas-Kogan and colleagues31 examined the role of RT on local control in the Children’s Cancer Group study 3891. It appears that both 10 Gy to the primary site as well as 10 Gy of total-body irradiation decreased the local recurrence rate. The largest benefit was seen when patients received both local RT and total-body irradiation, for a total dose of 20 Gy. Because RT was not randomized in this study, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions, yet these data, along with single-institution data, argue that RT to the primary site improves outcomes in high-risk patients. Currently, the Children’s Oncology Group recommends 21.6 Gy in once-daily fractions of 1.8 Gy to the primary tumor site with myeloablative chemotherapy that does not include total-body irradiation. The ideal timing for RT is after myeloablative chemotherapy and resection, when the volume of disease is minimal.

Targeted radiopharmaceuticals are also under investigation as an alternative means of delivering specific RT to metastatic tumor sites, either for refractory disease or as part of a myeloablative regimen. Targeted radioisotope therapy using anti-GD2 antibody or MIBG for delivery of radiation in the form of iodine-131 has been tested extensively in clinical trials in patients with relapsed neuroblastoma. Kushner and associates32 have reported on the use of 131I-3F8 (anti-GD2 antibody) for treatment of refractory neuroblastoma with excellent responses, especially for disease in the bone marrow. They have also treated newly diagnosed patients using 131I-3F8 in high doses followed by bone marrow rescue and further treatment with cold antibody after transplant.

Recurrent Disease and Palliation

Current approaches for treating recurrent or refractory neuroblastoma include novel cytotoxic agents and targeted delivery of radionuclides, retinoids, and immunotherapy. Topotecan, paclitaxel, irinotecan, rebeccamycin, and oral etoposide are the most frequently investigated cytotoxic agents.32–36 RT plays an important role in palliation for neuroblastoma. Patients with incurable disease often live for an extended period of time. However, they often suffer severe pain and functional impairment from metastases, most commonly to bone. External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is the most effective tool for managing painful metastases. Fractionation schemes depend on the site, field size, marrow reserves, and anticipated life span of the patient. A high-functioning child may benefit from 2-Gy fractions to 30 Gy, whereas a patient with end-stage disease may be better served by a single fraction of 7 to 8 Gy.

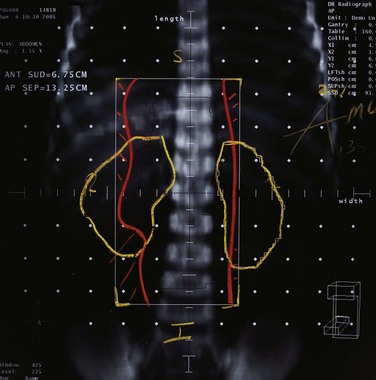

Irradiation Techniques

Irradiation techniques depend on the site being treated. Most commonly, patients with high-risk disease have a primary tumor arising from the adrenal gland. Radiation volume for localized neuroblastoma is determined by the surgeon’s operative findings and presurgical imaging studies. Margins and normal tissue-sparing parameters vary from protocol to protocol. Based on patterns of failure data, it is important to include the para-aortic lymph nodes in the radiation field.37 Computed tomographic planning is imperative to delineate precisely the target region as well as normal tissues, including the kidneys, liver, and, in some cases, ovaries. Treatment should encompass entire vertebral bodies to reduce the risk of scoliosis. Simple anterior and posterior beams, as demonstrated in Figure 70-2, are often the best solution, but intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) may be helpful if standard techniques do not provide adequate sparing of critical organs. Bone metastases are also often best treated with simple opposed beams. However, more sophisticated approaches, such as IMRT, may be needed when treating sites in the head and neck because of the complex anatomy and critical structures.

Treatment Algorithms, Controversies, Challenges, Future Possibilities, and Clinical Trials

Intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT) has been studied as an alternative to EBRT. Gillis and colleagues38 reported results for 31 patients who received IORT with electron-beam energies that ranged from 4 to 16 MeV, and the median dose was 10 Gy (range, 7 to 15 Gy). They concluded that IORT for the primary tumor produced excellent local control after a gross total resection but was inadequate after a subtotal resection. However, a follow-up publication by the University of California, San Francisco, group reported a high rate of severe aortic complications in patients receiving IORT.39 Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center reported a relatively favorable 50% rate of local control and low rate of complications for 44 patients who underwent subsequent surgery and re-irradiation with IORT for locally relapsed neuroblastoma.40

Iodine-131(131I)-labeled MIBG therapy is one example of targeted radiation. 131I-MIBG is bound at the cell membrane and is actively transported into cells by most neuroblastomas. Therapeutic use of 131I-MIBG has been used in patients with unresectable disease with excellent results. Trials combining 131I-MIBG with chemotherapy, surgery, and RT are currently in progress. In addition to 13-cis-retinoic acid, new retinoids are being developed to treat recurrent or refractory disease. Fenretinide is one such compound that induces apoptosis even in cells resistant to 13-cis-retinoic acid.39

The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center has excellent long-standing results using the 3F8 murine monoclonal antibody against GD2.40 More recently, a randomized study41 confirmed superior event-free and overall survival when high-risk patients received consolidation with immunotherapy. They used a chimeric human-murine anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody that was given in alternating sequence with granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-2. Two-year event-free survival was 66% with immunotherapy compared with 46% in the control group.

Consideration for long-term complications is critical when treating neuroblastoma. Patients treated years ago with higher doses of radiation frequently suffered from spinal deformities secondary to surgery and RT.42 Major orthopedic problems from RT still occur but are infrequent with a dose of 21 Gy. Symmetric treatment of vertebral bodies is recommended.

It is possible that the kidneys of infants and young children are more sensitive to RT than are those of adults and older children. Abnormal creatine clearance has been reported in infants with stage IVS disease who received 12.25 and 14 Gy.43 As a general rule, it is desirable to limit as much of each kidney as possible to doses less than 15 to 18 Gy to prevent major impairment in renal function. One must also inform parents about the low risk of second malignancies.44 A recent study of long-term survivors of high-risk neuroblastoma shows that the majority have late complications of therapy, including hearing loss, hypothyroidism, ovarian failure, musculoskeletal abnormalities, and pulmonary dysfunction. However, most complications were considered to be of mild-to-moderate severity.45 All members of multimodality teams that care for neuroblastoma patients must be mindful of late effects and strive to minimize complications while ensuring the best chance for cure.

1 Smith M, Ries L, Gurney J. Cancer incidence and Survival Among Children and Adolescents. United States SEER Program 1975-1995. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 1999.

2 Brodeur G, Maris J. Neuroblastoma. In: Pizzo P, Poplack D, editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. ed 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:895-937.

3 Halperin E, Constine L, Tarbell N, Kun L. Neuroblastoma. In Pediatric Radiation Oncology, ed 3, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:163-203.

4 Schilling FH, Spix C, Berthold F, et al. Neuroblastoma screening at one year of age. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1047-1053.

5 Beckwith J, Perrin E. In situ neuroblastomas. A contribution to the natural history of neural crest tumors. Am J Pathol. 1963;43:1089.

6 Ikeda Y, Lister J, Bouton JM, Buyukpamukcu M. Congenital neuroblastoma, neuroblastoma in situ, and the normal fetal development of the adrenal. J Pediatr Surg. 1981;16:636.

7 Kushner BH, Gilbert F, Helson L. Familial neuroblastoma. Case reports, literature review, and etiologic considerations. Cancer. 1986;57:1887.

8 Fong CT, Dracopoli NC, White PS, et al. Loss of heterozygosity for the short arm of chromosome 1 in human neuroblastomas. Correlation with N-myc amplification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:3753.

9 Brodeur GM, Seeger RC, Schwab M, et al. Amplification of N-myc in untreated neuroblastomas correlates with advanced disease stage. Science. 1984;224:1121-1124.

10 Matthay KK. Neuroblastoma. Biology and therapy. Oncology. 1997;11:1857-1866.

11 Delellis RA. The adrenal glands. In: Sternbert SS, editor. Diagnostic Surgical Pathology, vol 1. New York: Raven Press; 1989:445.

12 Croog VJ, Kramer K, Cheung NK, et al. Whole neuraxis irradiation to address central nervous system relapse in high-risk neuroblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:849-854.

13 Golding SJ, McElwain TJ, Husband JE. The role of computed tomography in the management of children with advanced neuroblastoma. Br J Radiol. 1984;57:661.

14 Fletcher BD, Kopiwoda SY, Strandjord SE, et al. Abdominal neuroblastoma. Magnetic resonance imaging and tissue characterization. Radiology. 1985;155:699.

15 Heisel MA, Miller JH, Reid BS, et al. Radionuclide bone scan in neuroblastoma. Pediatrics. 1983;71:206.

16 Voute PA, Hoefnagel C, Marcuse HR, et al. Detection of neuroblastoma with [I-131]meta-iodobenzylguanidine. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1985;175:389-398.

17 Brodeur GM, Pritchard J, Berthold F, et al. Revisions in the international criteria neuroblastoma diagnosis, staging and response to treatment. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1466.

18 LaBrosse EH, Comay E, Bohuan C, et al. Catecholamine metabolism in neuroblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976;57:633-643.

19 Evans AE, DAngio G, Randolph J. A proposed staging for children with neuroblastoma. Children’s Cancer Study Group A. Cancer. 1971;27:374.

20 Nitschke R, Smith EI, Shochat S, et al. Localized neuroblastoma treated by surgery. A Pediatric Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:1271.

21 Hayes FA, Green A, Hustu HO, et al. Surgicopathologic staging of neuroblastoma. Prognostic significance of regional lymph node metastases. J Pediatr. 1983;102:59-62.

22 Perez CA, Matthay KK, Atkinson JB, et al. Biologic variables in the outcome of stages I and II neuroblastoma treated with surgery as primary therapy. A Children’s Cancer Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:18-26.

23 Cohn SL, Look AT, Joshi VV, et al. Lack of correlation of N-myc gene amplification with prognosis in localized neuroblastoma. A Pediatric Oncology Group study. Cancer Res. 1995;55:721-726.

24 Nickerson HJ, Matthay KK, Seeger RC, et al. Favorable biology and outcome of stage IV-S neuroblastoma with supportive care or minimal therapy. A Children’s Cancer Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:477-486.

25 Matthay KK, Sather HN, Seeger RC, et al. Excellent outcome of stage II neuroblastoma is independent of residual disease and radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:236-244.

26 Castleberry RP, Kun LE, Shuster JJ, et al. Radiotherapy improves the outlook for patients older than 1 year with Pediatric Oncology Group stage C neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:789-795.

27 Matthay KK, Lukens J, Stram D, et al. Improving survival from 1978-1995 using risk based treatment for neuroblastoma: Children’s Cancer Group (CCG). Med Pediatr Oncol. 1996;27:220.

28 Matthay KK, Villablanca JG, Seeger RC, et al. Treatment of high-risk neuroblastoma with intensive chemotherapy, radiotherapy, autologous bone marrow transplantation, and 13-cis-retinoic acid. Children’s Cancer Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1165-1173.

29 Matthay KK, Castelberry RP. Treatment of advanced neuroblastoma. The U.S. experience. In: Brodeur GM, Sawada T, Tsuchida Y, Voute PA, editors. Neuroblastoma. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 2000:437-452.

30 Kushner BH, Wolden S, La Quaglia MP, et al. Hyperfractionated low-dose radiotherapy for high-risk neuroblastoma after intensive chemotherapy and surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2821-2828.

31 Haas-Kogan DA, Swift PS, Selch M, et al. Impact of radiotherapy for high-risk neuroblastoma. A Children’s Cancer Group study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:28-39.

32 Kushner BH, Kramer K, Cheung NK. Phase II trial of the anti-G(D2) monoclonal antibody 3F8 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4189-4194.

33 Saylors RLIII, Stewart CF, Zamboni WC, et al. Phase I study of topotecan in combination with cyclophosphamide in pediatric patients with malignant solid tumors. A Pediatric Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 1989;16:945-952.

34 Furman WL, Stewart CF, Poquette CA, et al. Direct translation of a protracted irinotecan schedule from a xenograft model to a phase I trial in children. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1815-1824.

35 Weitman S, Moore R, Barrera H, et al. In vitro antitumor activity of rebeccamycin analog (NSC #655649) against pediatric solid tumors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1998;20:136-139.

36 Davidson A, Gowing R, Lowis S, et al. Phase II study of 21 day schedule oral etoposide in children. New Agents Group of the United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group (UKCCSG). Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:1816-1822.

37 Wolden SL, Gollamudi SV, Kushner BH, et al. Local control with multi-modality therapy for stage 4 neuroblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46:969-974.

38 Gillis AM, Sutton E, Dewitt KD, et al. Long-term outcome and toxicities of intraoperative radiotherapy for high-risk neuroblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:858-864.

39 Sutton EJ, Tong RT, Gillis AM, et al. Decreased aortic growth and middle aortic syndrome in patients with neuroblastoma after radiation therapy. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39:1194-1202.

40 Rich BS, McEvoy MP, LaQuaglia MP, et al. Local control, survival, and operative morbidity and mortality after re-resection, and intraoperative radiation therapy for recurrent or persistent primary high-risk neuroblastoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:97-102.

41 Yu AL, Gilman AL, Ozkaynak MF, et al. and the Children’s Oncology Group: Anti-GD2 antibody with GM-CSF, interleukin-2, and isotretinoin for neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1324-1334.

42 Paulino AC, Mayr NA, Simon JH, et al. Locoregional control in infants with neuroblastoma. Role of radiation therapy and late toxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:1025-1031.

43 Peschel RE, Chen M, Seashore J. The treatment of massive hepatomegaly in stage IV-S neuroblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1981;7:549-553.

44 Kushner BH, Cheung NK, Kramer K, et al. Neuroblastoma and treatment-related myelodysplasia/leukemia. The Memorial Sloan-Kettering experience and a literature review. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3880-3889.

45 Laverdiere C, Cheung NK, Kushner BH, et al. Long-term complications in survivors of advanced stage neuroblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:324-332.