Chapter 14 Visual Loss

Visual loss commonly accompanies neurological disease and is one of the most disturbing symptoms a patient may experience. While visual loss is often due to a benign or treatable process, it can be the first sign of a blinding or life-threatening disease. Common causes of visual loss include uncorrected refractive error, corneal disease, cataract, glaucoma, retinal and choroidal disease, and amblyopia. Ophthalmic causes of visual loss are often not apparent to the neurologist, whereas neurological causes of visual loss often confuse ophthalmologists. Thus, the approach to evaluating visual loss must be systematic, so that important causes are not missed and simple causes are not overinvestigated. In this chapter, we discuss the patterns and temporal profiles of visual loss; examination techniques are discussed in Chapter 36 and funduscopic abnormalities are discussed in Chapter 15.

Pattern of Visual Loss

Central Visual Loss

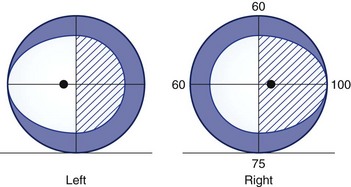

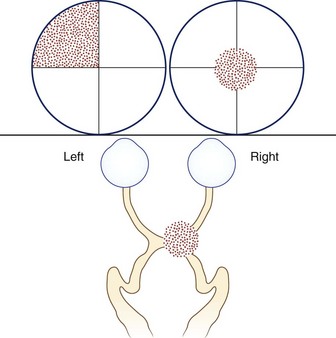

A defect in the visual field surrounded by normal vision is called a scotoma, from the Greek word meaning “darkness.” Loss of central vision, resulting in a central or cecocentral scotoma, is usually quickly noticed and reported. Peripheral visual field defects, such as homonymous hemianopia, can be asymptomatic but when noticed are frequently referred to the eye with the greater extent of field loss (i.e., the eye with temporal field loss) (Fig. 14.1). Central and cecocentral scotomas are usually due to lesions of the central retina or optic nerve. When the lesion is at the junction of the optic nerve and chiasm, there will be an ipsilateral central scotoma due to optic nerve involvement, and a contralateral temporal defect due to chiasmal involvement; this highly-localizing visual field defect is known as a junctional scotoma (Fig. 14.2). Patients with junctional scotomas are often unaware of the contralateral temporal defect, emphasizing the importance of assessing each eye separately during history taking and visual field evaluation.

Fig. 14.2 Junctional scotoma from a lesion at the junction of the optic nerve and chiasm. The lesion affects both the right optic nerve, producing a cecocentral scotoma in the right eye, and crossing fibers in the optic chiasm, producing an upper temporal visual field defect in the left eye. The temporal field defect of a junctional scotoma often goes unnoticed by the patient and may only be detected with visual field testing (see Chapter 36).

In general, scotomas caused by retinal disease are so-called positive scotomas, since they are perceived as a black or gray spot in the visual field. Patients with macular pathology can also have metamorphopsia, where there is distortion of images such that straight edges or geometrical figures appear warped. Metamorphopsia is almost always caused by retinal disease. In contrast, optic nerve lesions characteristically produce negative scotomas, areas of absent vision that are otherwise not perceivable, in conjunction with decreased color vision, contrast vision, and light brightness perception. On occasion, paradoxical photophobia, especially with fluorescent lighting, can occur with optic nerve lesions. Photopsias (light flashes) can occur with vitreoretinal traction (e.g., posterior vitreous detachment), retinal disease (e.g., cancer-associated retinopathy), toxicity from certain drugs (e.g., digitalis), or optic nerve disease (e.g., in the healing phase of optic neuritis, in which case they may be evoked by sound). Photopsias can also occur as part of migrainous visual aura. Aside from ocular diseases, bilateral central visual loss can result from lesions involving both optic nerves, the optic chiasm, or the part of the occipital cortex concerned with central vision. The possibility of nonorganic visual loss must also be considered, but it remains a diagnosis of exclusion (see Chapter 36).

Peripheral Visual Loss

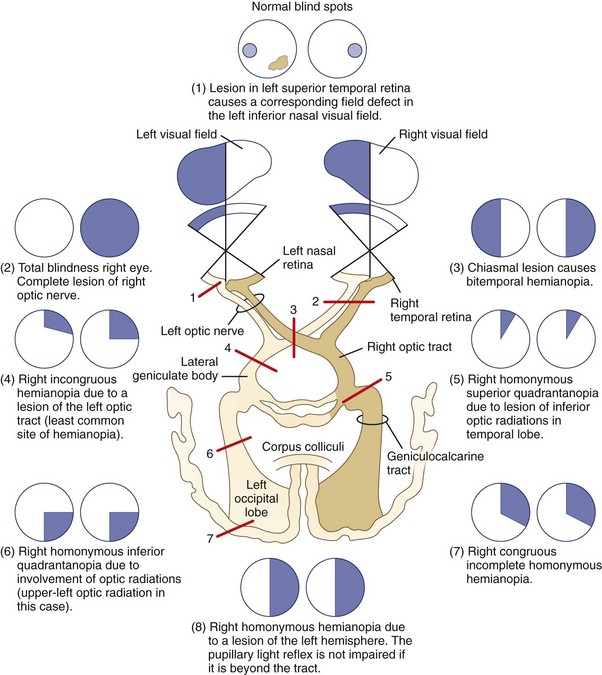

For simplicity, visual field defects can be classified into one of three groups: prechiasmal, chiasmal, or retrochiasmal. Unilateral prechiasmal lesions affect the visual field of one eye only, chiasmal lesions affect the fields of both eyes in a non-homonymous bitemporal fashion, and retrochiasmal lesions cause homonymous field defects with variable degrees of congruity (i.e., similarity) depending on their location (Fig. 14.3). See Chapter 36 for further discussion of patterns of visual field loss.

Temporal Profile of Visual Loss

Sudden-Onset Visual Loss

Visual loss of sudden onset can be divided into three temporal patterns: transient (Box 14.1) (Thurtell and Rucker, 2009), nonprogressive, and progressive.

Box 14.1 Causes of Transient Monocular Visual Loss

Transient Monocular Visual Loss

Amaurosis Fugax

The term amaurosis fugax is often used to describe the transient monocular visual loss (TMVL) caused by emboli from the carotids, aortic arch, or heart to the retinal circulation. Typically, these attacks are sudden in onset, last from several to 15 minutes, and are characterized by altitudinal visual field loss that is often described as being like a curtain descending over the eye (Donders, 2001). Patients may also describe having separate attacks with hemispheric symptoms, such as weakness and speech disturbance, rather than visual loss.

Retinal Artery Vasospasm

Transient monocular visual loss can be caused by retinal artery vasospasm and is called retinal migraine when accompanied by migraine headache (Hill et al., 2007). Vasospastic TMVL is usually benign and often responds to calcium channel blockers (Winterkorn et al., 1993).

Visual Loss in Bright Light

Some patients with reduced blood supply to the eye due to a high-grade stenosis or occlusion of the internal carotid artery report TMVL in bright light, which is likely due to impaired regeneration of photopigments secondary to ocular ischemia (Kaiboriboon et al., 2001). The TMVL can also occur following meals or with postural changes. A variety of ophthalmic abnormalities, including midperipheral retinal hemorrhages, can be present and collectively comprise the ocular ischemic syndrome (Chen and Miller, 2007). Other retinal diseases, such as cone dystrophies and age-related macular degeneration, can cause evanescent visual loss in bright light, also known as hemeralopia or day blindness. The visual loss in these diseases is usually bilateral, whereas it is unilateral in patients with unilateral carotid disease.

Transient Binocular Visual Loss

Other than transient visual obscurations occurring in patients with bilateral optic disc edema, simultaneous complete or incomplete transient binocular visual loss is almost always due to transient dysfunction of the visual cortex. Visual migraine aura is probably the most common cause of transient binocular visual loss, especially in patients younger than 40 years (see Chapter 69). Transient binocular visual loss can also result from cerebral hypoperfusion due to vasospasm, thromboembolism, systemic hypotension, hyperviscosity, or vascular compression (Box 14.2) (Thurtell and Rucker, 2009). Transient binocular visual loss can occur in association with seizures, although they more commonly cause visual hallucinations, which can be elementary or complex depending on the location of the seizure focus (Bien et al., 2000). Transient cortical blindness can occur in association with headache, altered mental status, and seizures in the posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (Hinchey et al., 1996). Transient cortical blindness can sometimes occur after head trauma, especially in children. Lastly, transient bilateral visual loss can occasionally be nonorganic in etiology, but this should remain a diagnosis of exclusion.

Sudden Monocular Visual Loss without Progression

Visual loss due to optic nerve or retinal ischemia is characteristically sudden in onset (Box 14.3) and is usually nonprogressive, although a stuttering decline in vision may occur over several weeks in approximately 10% of patients with anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy is a common cause of optic neuropathy and occurs secondary to loss of blood supply to the optic nerve head, resulting in optic disc edema (Rucker et al., 2004). In affected patients younger than 60 years, it is usually nonarteritic in etiology, being caused by a combination of factors that impair blood supply to the optic nerve head. In patients older than 60 years, giant cell (temporal or cranial) arteritis must be considered; urgent investigations and empirical treatment with high-dose steroids may be required in these patients to prevent further devastating visual loss. Retrobulbar optic nerve infarction, also known as posterior ischemic optic neuropathy, is far less common but can result from perioperative hypotension (e.g., with spinal surgery or cardiac bypass surgery) and other causes of hemodynamic shock (Rucker et al., 2004). Giant cell arteritis should be specifically considered in elderly patients with posterior ischemic optic neuropathy.

Box 14.3 Causes of Sudden Monocular Visual Loss without Progression

Optic nerve ischemia very rarely results from embolism or migraine. In contrast, central or branch retinal artery occlusions are caused mostly by embolic or thrombotic events. Opacification of the retinal nerve fiber layer with a cherry-red spot at the macula is the classic funduscopic appearance of acute central retinal artery occlusion (see Chapter 15). Retinal arterial occlusions can produce altitudinal, quadrantic, or complete monocular visual loss. The triad of branch retinal artery occlusions, hearing loss, and encephalopathy results from a rare microangiopathy known as Susac syndrome (Susac et al., 2007). A distinctive pattern of white-matter lesions with involvement of the corpus callosum is seen on magnetic resonance imaging in this disease.

Idiopathic central serous retinopathy can manifest as a positive scotoma of sudden onset, often with symptoms of metamorphopsia or micropsia and a positive light-stress test result (see Chapter 36). It results from leakage of fluid into the subretinal space and most often occurs in young adult men with type-A personalities. The diagnosis can be difficult to make without the aid of fluorescein angiography or optical coherence tomography, as the retinal findings are subtle. Spontaneous recovery usually occurs within weeks to months, but occasionally laser photocoagulation is required to seal leaking vessels.

Traumatic optic neuropathy (TON) usually results in sudden permanent optic nerve dysfunction. The trauma can be severe or deceptively minor, causing a contusion or laceration of the optic nerve in its canal or a shearing of its nutrient vessels with subsequent ischemia. Treatments for TON, such as steroids, remain controversial and mostly ineffective (Levin et al., 1999).

Sudden Binocular Visual Loss without Progression

Sudden, permanent, binocular visual loss, if not caused by trauma, most commonly results from a stroke involving the retrochiasmal visual pathways and causes an homonymous visual field defect (Box 14.4) (Rizzo and Barton, 2005). In patients who have no other neurological symptoms or signs, the lesion usually involves the occipital lobe. Bilateral occipital lobe infarcts can result in tubular visual field defects, checkerboard visual field defects, or complete loss of vision in both eyes, a condition called cortical blindness. Cortical blindness, especially from infarction, can be accompanied by a denial of the visual loss and confabulation, a condition known as Anton syndrome.

Sudden binocular visual loss can result from simultaneous bilateral ischemic optic neuropathies and chiasmal compression due to pituitary apoplexy. Pituitary apoplexy can also cause headache, diplopia, altered mental status, and hemodynamic shock (Sibal et al., 2004), but the presentation can be subtle such that the diagnosis is missed.

Sudden Visual Loss with Progression

Sudden-onset, painful monocular visual loss that subsequently worsens is commonly due to optic nerve inflammation (optic neuritis). The visual loss typically progresses over hours to days before stabilizing and then improving. Optic neuritis is well known to be associated with multiple sclerosis and may be the first sign of the disease. The prognosis for visual recovery without treatment is excellent in most patients, although there is a poor recovery in some, such as those with optic neuritis occurring in association with neuromyelitis optica (Wingerchuk et al., 2007).

Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON), a maternally transmitted disease resulting from mutations in the mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) genes encoding subunits of respiratory chain complex I, can also cause sudden visual loss with subsequent progression. Primary mutations have been identified at positions 11778, 3460, 15257, and 14484 in the mitochondrial DNA. Many other mutations have been reported but occur less frequently (Yu-Wai-Man et al., 2009). LHON produces acute or subacute painless, often permanent, central visual loss, usually in young adult men. The visual loss is initially monocular, but the other eye usually becomes affected within 6 months. Visual recovery is variable and infrequent, and depends on the mitochondrial DNA mutation. The 11778 mutation carries the worst visual prognosis and the 14484 mutation the best. In the acute phase, the classic triad of ophthalmic findings includes telangiectatic vessels around the optic disc, nonedematous elevation of the optic disc, and absence of leakage from the disc on fluorescein angiography. Arteriolar narrowing can be marked, and vascular tortuosity is often a clue early in the disease. LHON can also cause loss of vision in women, but it tends to be less severe than in men.

Careful questioning of the patient with “sudden” visual loss may reveal a long-standing deficit that has suddenly been noticed (e.g., when covering the good eye) or that has worsened over time. In such cases, the clinician should evaluate for a slow-growing compressive lesion (Box 14.5).

Progressive Visual Loss

Progressive visual loss is the hallmark of a lesion compressing the afferent visual pathways. Common compressive lesions include pituitary tumors, aneurysms, craniopharyngiomas, and meningiomas (see Box 14.5) (Gittinger, 2005; Glaser, 1999). Granulomatous disease of the optic nerve from sarcoidosis or tuberculosis can cause chronic progressive visual loss. Optic nerve compression at the orbital apex from thyroid-associated orbitopathy can occur with minimal orbital signs or ocular motility disturbance. In each of these cases, the visual loss can be so insidious as to go unnoticed until it is fortuitously discovered during a routine examination.

Hereditary or degenerative diseases of the optic nerves or retina must be included in the differential diagnosis of gradual-onset visual loss. The hereditary optic neuropathies are bilateral and are usually diagnosed during the first 2 decades of life (Yu-Wai-Man et al., 2009). The most common inherited optic neuropathy is the autosomal dominant variety, known as dominant optic atrophy. A number of mutations involving the OPA1 gene have been described in dominant optic atrophy (Yu-Wai-Man et al., 2009). The visual loss can range from mild to severe and can sometimes be asymmetrical. Characteristically, there are central or cecocentral scotomas with sparing of the peripheral fields, and temporal pallor and cupping of the optic discs. Color vision is usually abnormal. Other ophthalmic and neurological abnormalities may be present.

Drusen of the optic nerve head are extracellular deposits of plasma proteins and a variety of inorganic materials that can compress optic nerve axons near the surface of the nerve head as they enlarge (Auw-Haedrich et al., 2002). Drusen are a common cause of pseudopapilledema and can produce visual field defects including arcuate defects, sectorial scotomas, blind spot enlargement, and generalized visual field constriction (Lee and Zimmerman, 2005). Loss of visual acuity is atypical but can result from development of a secondary choroidal neovascular membrane, with subsequent hemorrhage into the macula, or anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. “Buried” drusen (i.e., those not visible with the ophthalmoscope) can also cause visual field loss; the diagnosis can be confirmed by identifying calcified deposits in the optic nerve head on ophthalmic ultrasound. Buried drusen can occasionally be seen with computed tomography if they are large enough, and appear as calcifications. If central visual loss occurs in patients with optic disc drusen and no obvious retinal lesion, a search for a retrobulbar lesion should be undertaken.

Normal-tension glaucoma (NTG) is a controversial entity that creates a diagnostic and therapeutic conundrum, since a number of conditions can give rise to a similar clinical picture (Tomsak, 1997). In true NTG, glaucomatous optic disc and visual field changes develop despite normal intraocular pressure. NTG is bilateral in 70% of patients, and the average age at diagnosis is 66 years. Women are affected approximately twice as frequently as men. NTG can be either progressive or static (Anderson et al., 2001).

Chronic papilledema from any cause of intracranial hypertension can produce progressive optic neuropathy (see Chapter 59). The optic discs often develop a milky gray color, and there is sheathing of peripapillary retinal vessels. The visual fields become constricted, with nasal defects occurring initially, followed by gradual constriction, with central vision being spared until late. Optociliary collateral vessels can develop, and sudden visual loss from ischemic optic neuropathy can rarely occur. On occasion, optic atrophy develops in the absence of papilledema or despite a decrease in intracranial pressure, possibly due to retrobulbar optic nerve compression (Thurtell et al., 2010).

Toxic and nutritional optic neuropathies are bilateral and usually progressive (Phillips, 2005; Tomsak, 1997). The nutritional variety is characterized by a history of inadequate diet, a gradual onset of painless visual loss over weeks to months, prominent dyschromatopsia, cecocentral scotomas, and development of optic atrophy late in the disease. Most cases of so-called tobacco-alcohol amblyopia are probably related to vitamin B deficiencies. Other conditions that lead to nutritional deficiency, such as bariatric surgery and ketogenic diet, can also cause bilateral optic neuropathies. Medications that are toxic to the optic nerves, including ethambutol, amiodarone, isoniazid, chloramphenicol, and iodoquinol (formerly diiodohydroxyquin), can cause a gradual onset of painless visual loss (Phillips, 2005). Retinal toxins such as vigabatrin, digitalis, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and phenothiazines can also cause painless progressive binocular visual loss.

Slowly progressive visual loss from radiation damage to the anterior visual pathways, especially the retina, can result from direct radiation therapy to the eye for primary ocular tumors or metastases, or can occur after periocular irradiation for basal cell carcinomas, sinus carcinomas, and related malignancies. It can also occur after whole-brain irradiation for metastases or gliomas, or after parasellar radiation therapy for pituitary or other parasellar neoplasms (Lessell, 2004). Radiation retinopathy becomes clinically apparent after a variable latent period of several months to a few years following the radiation therapy and is usually irreversible. Its incidence relates to the fraction size, total radiation dose, and use of concomitant chemotherapy. Radiation-induced retinal capillary endothelial cell damage is the initial event that triggers the retinopathy, which is usually indistinguishable from diabetic retinopathy.

Rapidly progressive bilateral visual loss in patients with cancer can be caused by paraneoplastic processes that affect the retina or optic nerves (Ko et al., 2008). Small cell carcinoma of the lung is the most commonly associated tumor, but gynecological, endocrine, breast, and other tumors have been implicated. The visual loss is usually accompanied by photopsias, often precedes the diagnosis of cancer, and is associated with circulating antibodies to the tumor and retinal or optic nerve antigens (see Chapter 52G). Findings similar to those of retinitis pigmentosa are present, including night blindness, constricted visual fields, and an extinguished electroretinogram. No effective treatment is available.

Anderson D.R., Drance S.M., Schulzer M., et al. Natural history of normal-tension glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:247-253.

Auw-Haedrich C., Staubach F., Witschel H. Optic disc drusen. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47:515-532.

Bien C.G., Benninger F.O., Urbach H., et al. Localizing value of epileptic visual auras. Brain. 2000;123:244-253.

Chen C.S., Miller N.R. Ocular ischemic syndrome: review of clinical presentations, etiology, investigation, and management. Compr Ophthalmol Update. 2007;8:17-28.

Donders R.C. Clinical features of transient monocular blindness and the likelihood of atherosclerotic lesions of the internal carotid artery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:247-249.

Gittinger J.W.Jr. Tumors of the pituitary gland. In: Miller N.R., Newman N.J., Biousse V., et al. Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology. sixth ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:1531-1546.

Glaser J.S. Topical diagnosis: the optic chiasm. In: Glaser J.S., editor. Neuro-ophthalmology. third ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:199-238.

Hill D.L., Daroff R.B., Ducros A., et al. Most cases labeled as “retinal migraine” are not migraine. J Neuroophthalmol. 2007;27:3-8.

Hinchey J., Chaves C., Appignani B., et al. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:494-500.

Kaiboriboon K., Piriyawat P., Selhort J.B. Light-induced amaurosis fugax. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:674-676.

Ko M.W., Dalmau J., Galetta S.L. Neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations of paraneoplastic syndromes. J Neuroophthalmol. 2008;28:48-68.

Lee A.G., Zimmerman M.B. The rate of visual field loss in optic nerve head drusen. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:1062-1066.

Lessell S. Friendly fire: neurogenic visual loss from radiation therapy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2004;24:243-250.

Levin L.A., Beck R.W., Joseph M.P., et al. The treatment of traumatic optic neuropathy: the International Optic Nerve Trauma Study. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1268-1277.

Phillips P.H. Toxic and deficiency optic neuropathies. In: Miller N.R., Newman N.J., Biousse V., et al. Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology. sixth ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:447-464.

Rizzo M., Barton J.J.S. Central disorders of visual function. In: Miller N.R., Newman N.J., Biousse V., et al. Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology. sixth ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:575-645.

Rucker J.C., Biousse V., Newman N.J. Ischemic optic neuropathies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004;17:27-35.

Sibal L., Ball S.G., Connolly V., et al. Pituitary apoplexy: a review of clinical presentation, management and outcome in 45 cases. Pituitary. 2004;7:157-163.

Susac J.O., Egan R.A., Rennebohm R.M., et al. Susac’s syndrome: 1975-2005 microangiopathy/autoimmune endotheliopathy. J Neurol Sci. 2007;257:270-272.

Thurtell M.J., Newman N.J., Biousse V. Visual loss without papilledema in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neuroophthalmol. 2010;30:96-98.

Thurtell M.J., Rucker J.C. Transient visual loss. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2009;49:147-166.

Tomsak R.L. Handbook of Treatment in Neuro-Ophthalmology, second ed. Boston: Butterworth Heinemann; 1997.

Wingerchuk D.M., Lennon V.A., Lucchinetti C.F., et al. The spectrum of neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:805-815.

Winterkorn J.M., Kupersmith M.J., Wirtschafter J.D., et al. Treatment of vasospastic amaurosis fugax with calcium-channel blockers. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:396-398.

Yu-Wai-Man P., Griffiths P.G., Hudson G., et al. Inherited mitochondrial optic neuropathies. J Med Genet. 2009;46:145-158.