49 Viral Diseases

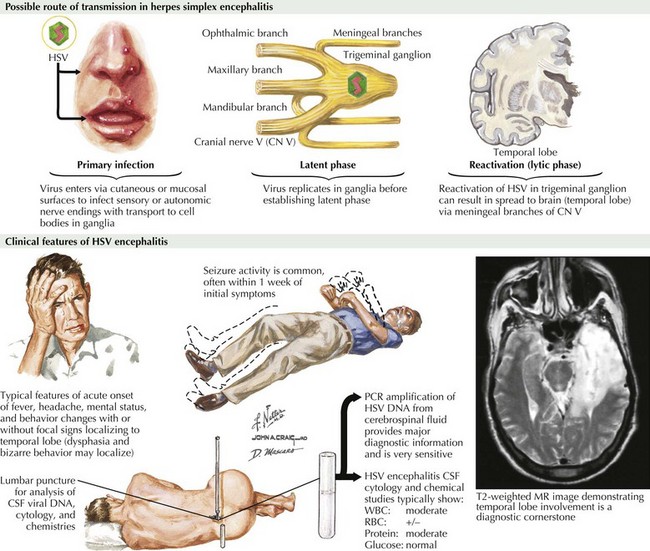

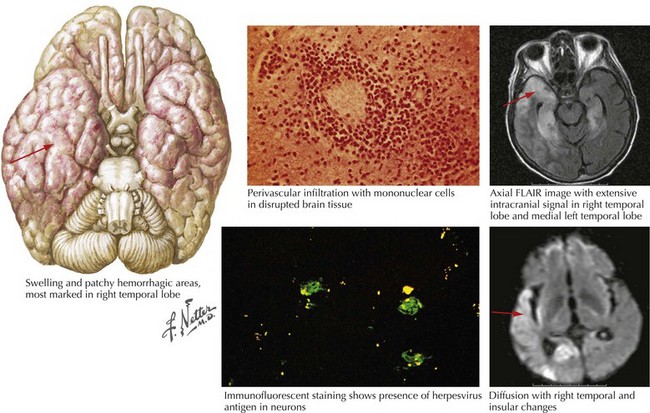

Herpes Simplex Encephalitis

Clinical Presentation

The symptoms and signs of patients with subacute or acute focal encephalitis are generally rather nonspecific, with fever, headache, and altered consciousness being the most common. Focal manifestations often include seizures, typically complex partial in character because of the temporal lobe’s predisposition to develop a herpes infection. It is common for these patients to also develop language difficulties, personality changes, hemiparesis, ataxia, cranial nerve defects, and papilledema (Fig. 49-1). The differential diagnosis includes stroke, brain tumors, other viral encephalitides, bacterial abscesses, tuberculosis, cryptococcal infections, and toxoplasmosis.

Diagnosis

For patients with suspected encephalitis, the initial diagnostic studies must include a CT scan (to rule out a mass effect) and then immediate CSF examination. CT scan results are abnormal in 50% of cases early on and usually demonstrate localized edema, low-density lesions, mass effects, contrast enhancements, or hemorrhage. MRI and EEG may be subsequently obtained for further confirmation. These usually demonstrate major temporal lobe damage (Fig. 49-2); however, a normal study does not exclude an HSE diagnosis. If such does occur, it is often wise to repeat the study within a few days, particularly if the patient continues to be confused.

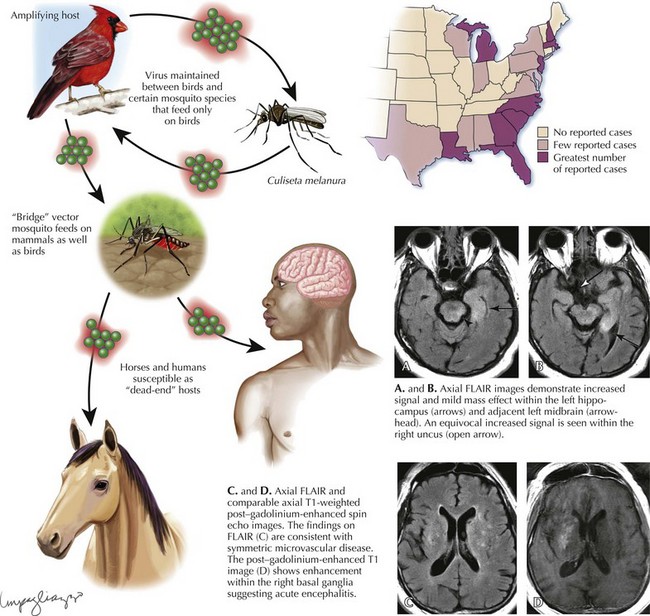

Eastern Equine Encephalitis

Diagnosis

Laboratory diagnosis of EEE virus infection is based on serology, especially IgM testing of serum and CSF, and neutralizing antibody testing of acute- and convalescent-phase serum. MRI is the most sensitive imaging modality for diagnosis of EEE (Fig. 49-3). The most commonly affected areas of the central nervous system (CNS) include the basal ganglia (unilateral or asymmetric, with occasional internal capsule involvement) and thalamic nuclei. Other areas include the brain stem (often the midbrain), periventricular white matter, and cortex (most often temporally). Affected areas appear as increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images.

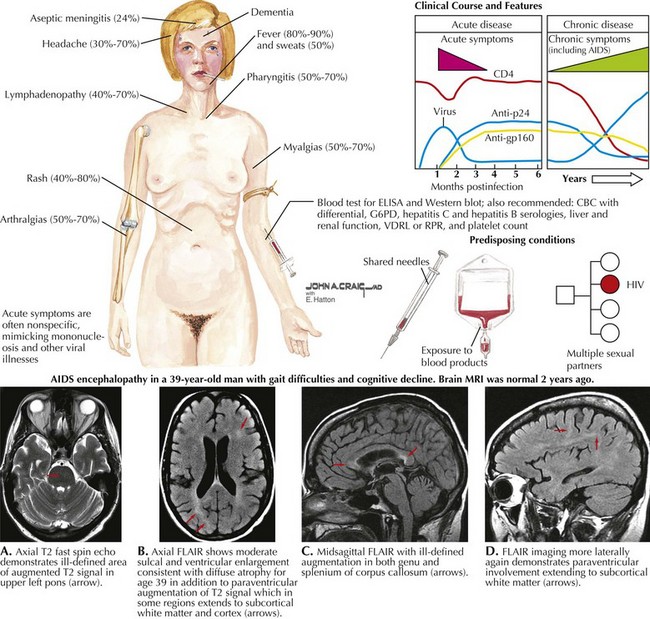

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

Primary Neurologic HIV Infection (PNHI)

Acute aseptic meningitis is the most common neurologic disorder to develop among individuals presenting with primary HIV infection (PNHI) (Fig. 49-4). Such patients present with headache, meningismus and sometimes myalgias, and arthralgias. As per the above vignette, on rare occasions, a meningoencephalitis, an encephalopathy, an acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, a myelopathy, a meningoradiculitis, and a peripheral neuropathy, particularly a Guillain–Barré syndrome may be seen as the presenting clinical picture of HIV. Other systemic symptoms and signs seen with acute HIV infection include fever, night sweats, weight loss, rash, fatigue, lymphadenopathy, oral ulcers, thrush, pharyngitis, gastrointestinal upset, and genital ulcers. As HIV antibody testing may be negative in PNHI, laboratory clues to the presence of seroconversion include leucopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated transaminases. In such cases, determination of serum HIV viral load may yield a positive result. A repeat HIV antibody study is often positive if the patient survives the initial neurologic illness. The primary infectious encephalitic forms have a significant morbidity and mortality perhaps as high as 50%. Its importance in adolescents is illustrated by the finding that in the United States, HIV is the seventh leading cause of death among patients aged 15–24 years. Once seroconversion occurs, AIDS patients are at risk for a host of neurologic complications.

HIV Dementia

AIDS dementia complex (ADC) is the most important “primary” neurologic complication of HIV infection. It is almost universal for HIV-1 infection to occur within the cerebrospinal fluid when AIDS is previously unrecognized and thus untreated. This was quite common early on in the AIDS epidemic prior to the availability of specific highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) protocols. These individuals presented with a varied dementia that was particularly characterized by early- to mid-adult-age changes in mental function. Such patients often were noted to have a relatively rapid to subacute change in personality with prominent apathy, inattention, inability to form new memory, and language dysfunction. ADC individuals were unable to carry out the basic requirements of normal activities of daily living. Although a number of AIDS patients develop a variety of opportunistic brain infections, as per Chapter 51, at autopsy many proved to have a primary subacute demyelinating process with some mild cellular response, particularly characterized by clusters of foamy macrophages, microglial nodules, and multinucleated giant cells.

HIV Myelopathy

Occasionally a primary vacuolar and inflammatory myelopathy is the presenting feature of AIDS. Its predisposition for the dorsal lateral spinal cord mimics the distribution and thus the clinical spectrum of B12 or copper deficiency syndromes (Chapter 45). There is no effective treatment for HIV-associated myelopathy. The introduction of HAART has made little difference to its natural history. Spinal cord pathology reveals vacuolization and inflammation.

HIV Anterior Horn Cell Myelopathy

Very rarely, one may see various forms of a motor neuron, anterior horn cell, disorder with HIV infection. This is attributed to direct HIV damage to the motor neurons by neurotoxic HIV viral proteins, cytokines and chemokines. Opportunistic viruses may also directly attack motor neurons in the AIDS clinical setting mirroring those of progressive spinal muscular atrophy (Chapter 67). This may result in an inexorably progressive disorder of upper and lower motor neurons. One most unusual presentation has been the rare patient presenting with severe bilateral arm and hand weakness unassociated with either bulbar and/or leg weakness or any corticospinal tract findings. This is referred to as a neurogenic “man-in-the-barrel” syndrome or brachial amyotrophic diplegia.

Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

Clinical Presentation

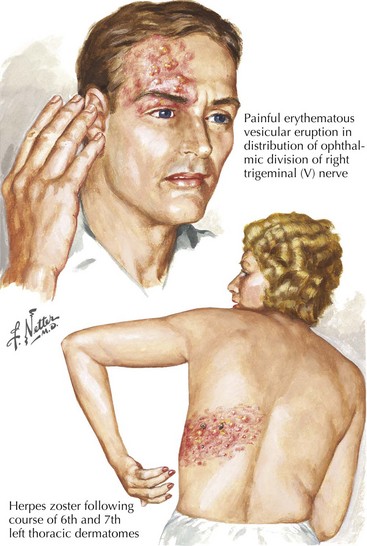

The eruption is unilateral and typically does not cross the midline. It overlaps adjacent dermatomes in 20% of cases. A vesicular skin rash, within a dermatomal distribution, forms the clinical signature of VZV reactivation in the dorsal root ganglion. Although any spinal segment or cranial nerve may be involved, the lower thoracic roots and the ophthalmic sensory ganglia are most commonly affected and thus a zoster rash is found frequently in these levels. Vesicles usually appear 72–96 hours later (Fig. 49-5). The lesions have an erythematous base with a tight, clear bubble that becomes opaque and crusts after 5–10 days.

Ophthalmic herpes zoster with involvement of the first division of the trigeminal nerve is the most common cranial nerve affected. If the rash involves the tip of the nose, it is likely that ophthalmic herpes zoster is present (Fig. 49-1). All patients with ophthalmic shingles require formal evaluation with a slit lamp and fluorescein study to assess any zoster dendrites and subsequent risk of corneal scarring. Surveillance is warranted because iritis and retinal necrosis may have delayed onset. Patients with this site of herpes zoster involvement are uniquely predisposed to developing a stroke from large vessel carotid vasculitis ipsilateral to the ophthalmic division involvement.

Rabies

Etiology and Epidemiology

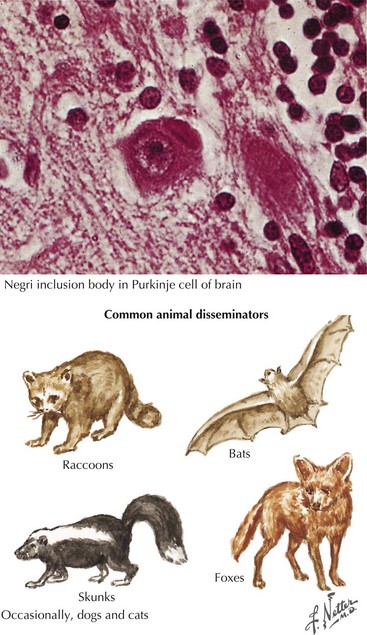

Animals predominantly infected and involved in rabies transmission vary by geographic area. During 2007 in the United States, 7258 cases of rabies were identified by the CDC in animals, representing a 4.6% increase. Approximately 93% of the cases were in wildlife, and 7% were in domestic animals. Relative contributions by the major animal groups included 2659 raccoons (36.6%), 1973 bats (27.2%), 1478 skunks (20.4%), 489 foxes (6.7%), 274 cats (3.8%), 93 dogs (1.3%), and 57 cattle (0.8%). This represents a significant increase in those related to bats and foxes with a diminution in the incidence of raccoon source whereas skunks maintain an important steady-state source (Fig. 49-5). Among domestic sources, cats are three times more likely than dogs to be a potential human source. Cases of rabies in dogs and in sheep and goats increased 17.7% and 18.2% in 2007, respectively, whereas cases reported in cattle, cats, and horses and mules decreased 30.5%, 13.8%, and 20.8%, respectively. These are unusual sources of animal rabies in the United States because of the prevalence of rabies vaccinations. Nevertheless, dog and cat bites continue to account for the vast majority of human rabies cases worldwide. Just one case of human rabies was reported in the United States in 2007.

Diagnosis

Clinical manifestations contrast strikingly with neuropathologic findings. Only mild congestion and perivascular inflammation are noted. The Negri body, a neuronal cytoplasmic inclusion with a dark central inner body, is pathognomonic of rabies at autopsy (Fig. 49-6).

Poliomyelitis

Pathogenesis

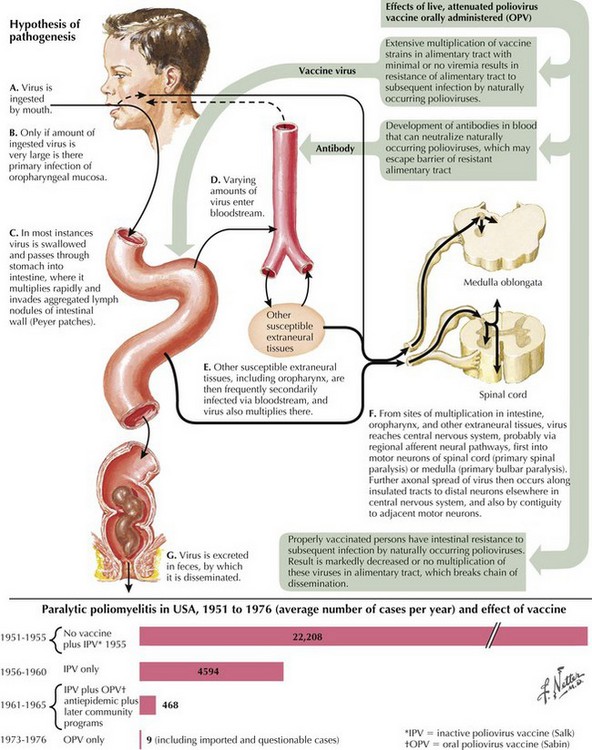

Poliovirus is a member of the family Picornaviridae, enterovirus subgroup. Enteroviruses are transient inhabitants of the gastrointestinal tract and are stable at acid pH. Picornaviruses have an RNA genome; the three poliovirus serotypes (P1, P2, and P3) have minimal heterotypic immunity among them. The virus enters through the mouth and multiplies primarily at the implantation site in the pharynx and gastrointestinal tract; usually, it is present in the throat and stool before clinical onset (Fig. 49-7). Within 1 week of clinical onset, little virus exists in the throat, but it continues to be excreted in the stool for several weeks. The virus invades local lymphoid tissue, enters the bloodstream, and then may infect CNS cells. Viral replication in anterior horn and brainstem motor neuron cells results in cell destruction and paralysis.

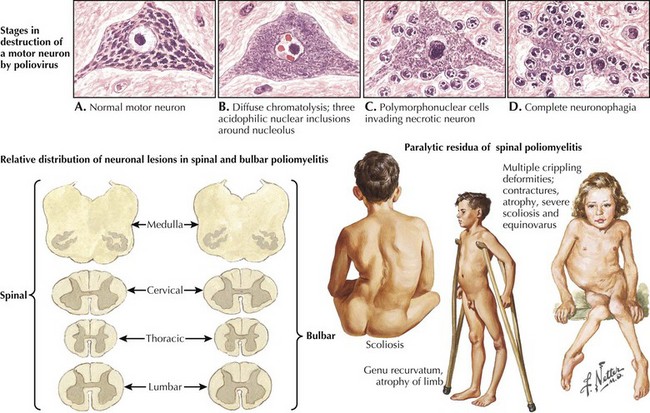

Clinical Presentation

Three types of paralytic polio are described. Most common is spinal polio (approximately 79% of cases in the 1970s), characterized by asymmetric paralysis usually involving the legs (Fig. 49-8). Bulbar polio (2%) causes weakness of muscles innervated by cranial nerves. Bulbospinal polio (19%) is a combination of the two. Mortality in paralytic polio cases is lower in children (2–5%) than in adults (15–30%) and highest (25–75%) with bulbar involvement.

Prognosis

Evidence

Power C, Boissé L, Rourke S, et al. Neuro AIDS: an evolving epidemic. Can J Neurol Sci 2009 May;36(3):285-295. Prevention of herpes zoster. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5705a1.htm Accessed April 28, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report summary of the clinical trials supporting efficacy of herpes zoster vaccine and recommendations for its use in adults ≥60 years of age

Arboviral encephalitides. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/Arbor/index.htm. Accessed April 28, 2011. Comprehensive site maintained by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that includes basic fact sheets on the most common arboviral encephalitides along with information about transmission and life cycles, current global epidemiology, and information about clinical presentation

CDC Shingles Vaccination website http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/shingles/default.htm Accessed April 28, 2011. Comprehensive resource on the herpes zoster vaccine, its use, and information about shingles

Tunkel AR, Glaser CA, Bloch KC, et al. The Management of Encephalitis: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:303-327. Available at http://www.idsociety.org/content.aspx?id=4430#en Accessed April 28, 2011. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with encephalitis prepared by an Expert Panel of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, intended for use by health care providers who care for patients with encephalitis. Includes data on the epidemiology; clinical features; diagnosis; and treatment of many viral, bacterial, fungal, protozoal, and helminthic etiologies of encephalitis and provides information on when specific etiologic agents should be considered in individual patients with encephalitis

World Health Organization Poliomyelitis web page http://www.who.int/topics/poliomyelitis/en/ Accessed April 28, 2011. Comprehensive resource with up-to-date information on global outbreaks, disease history and clinical findings, and current eradication efforts