96 Vertigo

• The majority of cases of vertigo arise from a peripheral source (e.g., cranial nerve VIII, vestibular structures) rather than a central source.

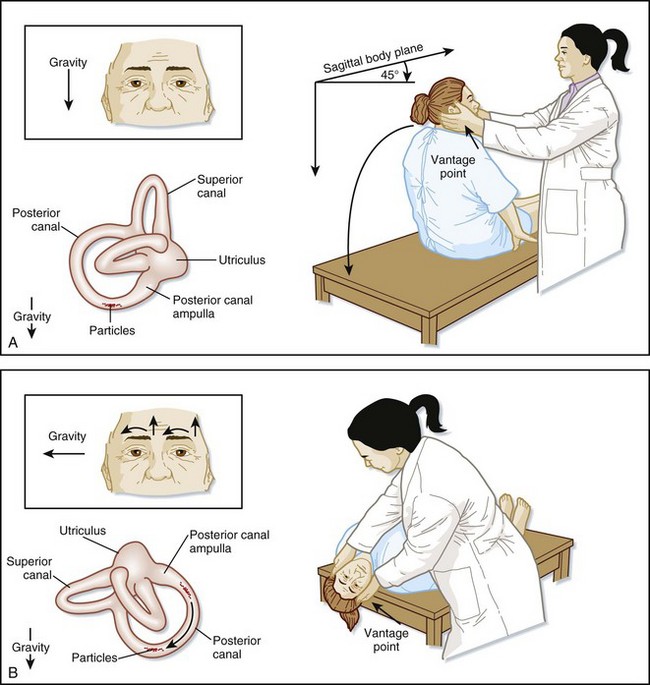

• The Dix-Hallpike test (also called the Nylan-Bárány test) can help confirm the diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

• Other causes should always be considered because the signs and symptoms of central vertigo can mimic those of peripheral vertigo.

• Central vertigo should be suspected in patients with any abnormal neurologic findings.

Peripheral Vertigo

Epidemiology

Pathophysiology

Nystagmus is an involuntary rhythmic movement of the eyes to and fro that is often seen in patients with vertigo. Nystagmus is defined in terms of the direction of the fast-phase component. The factors listed in Table 96.1 should be noted in all patients with nystagmus. It should be kept in mind that on extremes of lateral gaze, several-beat nystagmus is a normal finding in 60% of patients.

| Direction | Left or right |

|---|---|

| Axis | Upbeat or downbeat |

| Nature | Rotary/torsional or vertical |

| Duration | Seconds, minutes, or persistent |

| Associated Factors | Spontaneous or positionalEffect of visual fixation |

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

BPPV results from a mechanical defect in the inner ear. Canalolithiasis is the most accepted hypothesis. According to this premise, the culprits are free-floating otoliths that have become displaced from the utricle and inappropriately enter and activate the end-organs of the semicircular canals.2 With certain head movements, a clump of otoliths moves, causes the endolymph to move with resultant inappropriate displacement of the cupula. Movement of the cupula triggers neural firing, with consequential vertigo and nystagmus. Less commonly, otoliths can adhere to the cupula and result in vertigo. This mechanism is called cupulolithiasis.

Vestibular Neuritis and Labyrinthitis

See Table 96.2 for the pathophysiology of other causes of peripheral vertigo.

Table 96.2 Pathophysiology of Various Causes of Peripheral Vertigo

| CAUSE | PATHOPHYSIOLOGY |

|---|---|

| BPPV | Otoliths inappropriately displaced into the semicircular canals |

| VN/L | Inflammation of the vestibular nerve |

| Meniere disease | Excessive endolymph in the vestibule |

| Posttraumatic vertigo | Trauma to the occiput or temporal area |

| Perilymph fistula | Abnormal opening between the middle and inner ear |

| Acoustic neuroma | Slowly expanding tumor compressing cranial nerve VIII |

BPPV, Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo; VN/L, vestibular neuritis/labyrinthitis.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Details of the patient’s history, as well as findings on physical examination, can help narrow the differential diagnosis (Box 96.1).

Box 96.1 Evaluation of Vertiginous Patients

Consider the following factors when questioning patients during emergency department evaluation:

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

The diagnosis of BPPV is confirmed with the Dix-Hallpike test,3 also called the Nylan-Bárány test (Fig. 96.1; Box 96.2).

Box 96.2 Findings on the Dix-Hallpike Test in Patients with Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

Latency is approximately 3 to 10 seconds.

Significant subjective vertigo is present.

The intensity of vertigo escalates and then slowly resolves.

Vertigo and nystagmus last for approximately 5 to 30 seconds.

The nystagmus is upbeat (toward the forehead) and torsional toward the abnormal ear.

The nystagmus often reverses direction when the patient returns to the seated position.

Fatigability—the vertigo and nystagmus decrease and eventually subside with repeated positioning.

Vestibular Neuritis and Labyrinthitis

Spontaneous nystagmus with peripheral features may be seen on examination. Postural imbalance with a tendency to fall toward the side with the lesion is also seen. Middle ear infection or serous fluid may be present. Patients have a positive head-thrust test,4 also known as the head impulse test.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Table 96.3 presents characteristics that differentiate peripheral from central vertigo.

Table 96.3 Characteristics Differentiating Peripheral from Central Vertigo

| SYMPTOMS | PERIPHERAL | CENTRAL |

|---|---|---|

| Latency | 3-10 sec | None |

| Intensity of vertigo | Marked | mild |

| Duration | <1 min | >1 min |

| Reproducibility | Variable | Present |

| Fatigability | Yes | No |

| Habituation | Yes | No |

| Nausea/vomiting | Moderate to severe | Variable |

| Nystagmus | Rotatory | Vertical or downbeat |

| Associated neurologic findings | Absent | Present |

Diagnostic Testing

Treatment

Short-term treatment with vestibular suppressants is useful in the management of peripheral vertigo (Table 96.4). The sensory conflict theory states that a mismatch of information from vestibular, visual, or proprioceptive input will temporarily result in nausea and vertigo but will resolve as habituation occurs. This mechanism occurs via γ-aminobutyric acid, acetylcholine, serotonin, and histamine receptors. In the emergency department (ED) setting, parenteral antiemetics such as benzodiazepines (e.g., valium, 2 to 5 mg intravenously), promethazine, and ondansetron are generally most helpful. Note that the Food and Drug Administration recently recommended that promethazine be administered only via the intramuscular route when given parenterally.

| CATEGORY | DRUG | DOSAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Anticholinergic | Scopolamine | 0.5-1.5 mg transdermally q3-4d |

| Antihistamine | Diphenhydramine | 25-50 mg IM, IV, or PO q4-6h |

| Meclizine | 25-50 mg PO q6-12h | |

| Promethazine | 12.5-25 mg IM, PO, or PR q6-8h | |

| Antiemetic | Hydroxyzine | 25-50 mg PO q6h |

| Promethazine | 12.5-25 mg IM, IV, or PO q6-12h | |

| Prochlorperazine | 5-10 mg PO q6-8h; 10-25 mg PR q6-12h | |

| Ondansetron | 4 mg IM, IV | |

| Benzodiazepine | Diazepam | 2-5 mg PO qd-tid |

| Clonazepam | 0.25-0.5 mg PO bid-tid |

Vestibular exercises such as Brandt-Daroff exercises may be helpful for BPPV, poorly compensated vestibular neuritis, end-stage Meniere disease, and chronic and psychiatric vertigo.5 These exercises, which can be performed in the physical therapy unit or at home, are based on the concept of fatigue and facilitation of central compensatory mechanisms.

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

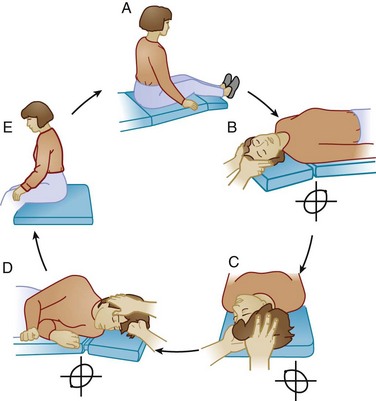

The Epley maneuver takes approximately 3 minutes and has been shown to be safe and effective in treating posterior canal BPPV.6 It is also easily performed in the ED setting. Gravity is used to move the otoliths out of the posterior semicircular canal into the utricle, where they will no longer cause vertigo.

Each position is held for approximately 30 seconds or until the symptoms and nystagmus resolve. It is currently recommended that the patient remain upright at least 20 minutes after the maneuver, which may be sufficient time for the otoliths to reattach to hair cells in the utricle (Fig. 96.2).

Fig. 96.2 Epley maneuver.

(Adapted from Timothy C. Hain, MD. Available at http://www.dizziness-and-balance.com/disorders/bppv/bppv.html.)

Patients with a positive roll test (indicating horizontal semicircular canal involvement) can be treated with the barbeque roll maneuver in which the patient is placed in the supine position with the head turned 90 degrees to the affected side as determined by the roll test. The head is then turned in 90-degree intervals in the opposite direction back to the original starting position. This requires the patient to eventually turn onto the abdomen. Each position is held for 30 seconds or until resolution of the vertigo and nystagmus. Anterior canal BPPV is diagnosed by a characteristic history, as well as by downbeat torsional nystagmus during the Dix-Hallpike test. Because downbeat (fast phase beating toward the feet) nystagmus can also indicate a central cause of vertigo and anterior canal involvement is extremely rare,7 the author cautions against making this diagnosis and recommends consideration of a central cause of vertigo.

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

BPPV is generally self-limited but recurs up to 50% of the time.7 Persistent or recurrent vertigo is managed with the maneuvers described previously. Vestibular suppressants may also be prescribed.

In some intractable incapacitating cases, patients may benefit from neurectomy or nonampullary plugging of the semicircular canal.9

Central Vertigo

Central vertigo occurs as a result of disorders of the CNS. Major causes of central vertigo are listed in Box 96.3. Migraine and stroke are emphasized in the rest of this section.

Box 96.3 Major Causes of Central Vertigo

Epidemiology

Migraine

The lifetime prevalence of migraine (16%) and vertigo (7%) leads to an expected comorbidity of the two conditions in 1.1% of the general population.10 A recent German survey, however, found a prevalence of 3.2%.11 Vestibular migraines are the most common cause of central vertigo and occur in 25% of patients suffering from migraines. Vestibular migraines tend to occur in women between the third and fifth decades of life.

Pathophysiology

Other

The pathophysiology of selected other causes of central vertigo are listed in Box 96.4.

Box 96.4 Pathophysiology of Other Causes of Central Vertigo

Lateral medullary syndrome (Wallenberg syndrome): ipsilateral ischemia (usually from the posterior inferior cerebellar artery or one of its branches) or rarely demyelination of the lower brainstem. Cranial nerves IX and X are most commonly affected.

Subclavian steal syndrome: occurs when blood is siphoned away from the central circulation to the left upper extremity, which leads to ischemia of the posterior circulation.

Rotational vertebral artery occlusion syndrome: turning of the head may cause occlusion of the vertebral artery at the C1-C2 level.

Vertebral artery dissection: sudden strain of the neck and even trivial injuries can cause dissection, which leads to ischemia of the posterior circulation. Blood penetrates the arterial wall and compresses the lumen or forms an aneurysmal dilation. Small emboli and subarachnoid hemorrhages may also occur.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Migraine

If a preceding aura occurs, the migraine will usually develop over a period of minutes and subside within an hour. This is followed by the acute onset of vertigo. Patients usually have an associated headache; however, vertigo may be the headache equivalent.12 Fluctuating low-frequency hearing loss and tinnitus can also occur (Box 96.5).

Box 96.5 Findings Associated with a Migrainous Etiology of Vertigo

Spontaneous or positional vertigo

Episodes lasting no more than a few days

Frequent recurrences within a year

Interferes with daily activities

History of motion sickness as a child

Symptoms associated with the vertigo

Migraine history according to International Headache Society criteria

Migraine-specific precipitants of vertigo

Migraine medications terminating the symptoms

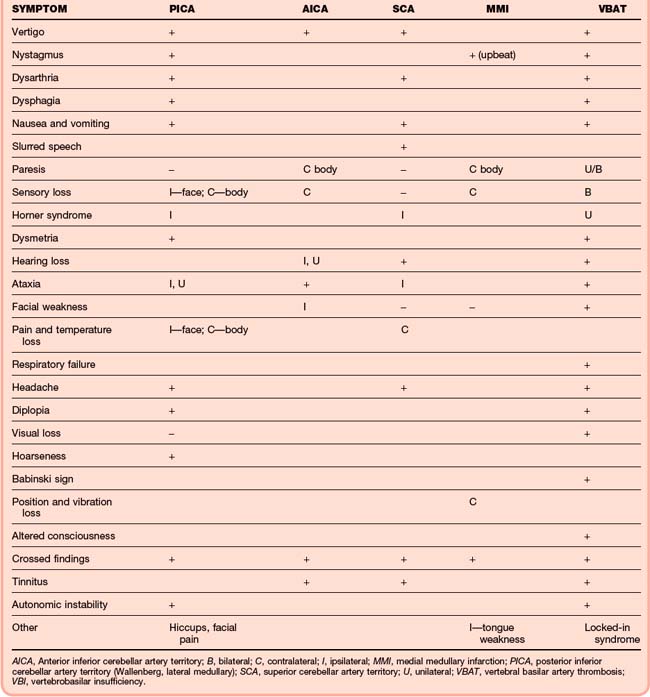

Stroke

Twenty percent of strokes involve the posterior circulation, which can affect the vestibular structures or pathways leading to vertigo. Symptoms of stroke vary depending on the affected anatomy and vasculature but often involve one or more of the “five D’s”: dizziness, diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, and dystaxia. The vascular structures most commonly affected by stroke and other lesions can be divided into anatomic territories, including the vertebrobasilar territory, the superior cerebellar artery territory, and the posterior inferior cerebellar artery territory (see Table 96.5).

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Baloh RW. Neurotology of migraine. Headache. 1997;37:615–621.

Hilton M, Pinder D. The Epley (canalith repositioning) maneuver for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2002. CD003162

Hoston JR, Baloh RW. Acute vestibular syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:680–685.

Lempert T, Von Brevern M. Episodic vertigo. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18:5–9.

Savitz S, Caplan L. Current concepts in vertebrobasilar disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2618–2626.

1 Lempert T, Von Brevern M. Episodic vertigo. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18:5–9.

2 Parnes LS, McCleure J. Free-floating endolymph particles: a new operative finding during posterior semicircular canal occlusion. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:988.

3 Dix MR, Hallpike CS. The pathology, symptomatology and diagnosis of certain common disorders of the vestibular system. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1952;61:987–1016.

4 Black RA, Halmagyi GM, Thurtell MJ, et al. The active head-impulse test in unilateral peripheral vestibulopathy. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:290–293.

5 Beyon GJ. A review of management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo; current status of medical management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:381–382.

6 Hilton M, Pinder D. The Epley (canalith repositioning) maneuver for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2002. CD003162

7 Honrubia B, Baloh RW, Harris MR, et al. Paroxysmal positional vertigo syndrome. Am J Otol. 1999;20:465–470.

8 Strupp M, Zingler VC, Niklas D, et al. Methylprednisolone, valacylovir or the combination for vestibular neuritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:354–361.

9 Minor LB. Superior canal dehiscence syndrome. Am J Otol. 2000;21:9–19.

10 Lempert T, Neuhauser H. Epidemiology of vertigo, migraine and vestibular migraine. J Neurol. 2009;256:333–338.

11 Neuhauser HK, Radtke A, von Brevern M, et al. Migrainous vertigo: prevalence and impact on quality of life. Neurology. 2006;67:1028–1033.

12 Harno H, Hirvonen T, Kaunisto MA, et al. Subclinical vestibulocerebellar dysfunction in migraine with and without aura. Neurology. 2003;61:1748–1752.

13 Montavont A, Nighoghossian N, Derex L, et al. Intravenous r-tPA in vertebrobasilar acute infarcts. Neurology. 2004;62:1854–1856.