71 Venous Thrombosis

• Distinction between symptoms of chronic venous disease and acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT) can be difficult. Careful attention to the time course of symptoms as reported by the patient and scrutiny of the medical record may reveal that the symptoms are less likely to be acute.

• The D-dimer blood test can be useful in the evaluation of potential DVT. Just as with pulmonary embolism, its use and interpretation need to take into account the pretest probability of disease.

• Many patients may not have classic, obvious risk factors for DVT but may still have the disease.

• The lack of 24-hour availability of duplex ultrasound, the imaging method of choice for DVT, requires a clear estimate of the probability of disease, the likelihood and timing of follow-up, and consideration of the risks and benefits of temporary empiric anticoagulation.

• Follow-up of patients is critical for monitoring the anticoagulation effects of warfarin, evaluation of progression of symptoms, and determination of the duration of anticoagulation.

Epidemiology

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a common diagnosis that may be seen in emergency department (ED) patients with minimal to no symptoms or with obvious findings on examination. DVT most typically arises in the lower part of the leg and may exist in combination with or as a precursor to pulmonary embolism (PE). Together, DVT and PE are termed venous thromboembolism (VTE). Understanding VTE as a single disease is useful because risk factors, urgency in establishing a diagnosis, and treatment are similar for both PE and DVT. The annual incidence of DVT has been estimated to be 92 cases per 100,000 persons, and the rate steadily advances with increased age (32/100,000 in persons younger than 55 years, 282/100,000 in those 65 to 74 years of age, and 553/100,000 in those 75 years or older).1

Pathophysiology

Typical DVT risk factors are summarized by the Virchow triad: trauma, stasis, and hypercoagulability. These risk factors are the same as for PE (Table 71.1). However, 25% to 50% of patients with DVT may have no identifiable risk factor known at the time of evaluation.

Table 71.1 Known Risk Factors for Acute Deep Vein Thrombosis

| RISK FACTORS | SPECIFIC NOTES |

|---|---|

| Previous history of PE or DVT | Inquire about the setting and circumstances of the previous VTE |

| Recent trauma or surgery | In general, trauma requiring admission or surgery requiring general anesthesia within the previous month. Recent long-bone, vascular, or trauma surgery may especially increase the risk |

| Cancer | In general, patients with currently treated cancer or palliative care |

| Central or long-term vascular catheters | |

| Age | Risk significantly increases above the age of 50 to 60 years |

| Oral contraceptives | Especially third-generation formulations |

| Hormone replacement therapy | Currently less common than in the past |

| Pregnancy | Risk increases along with the duration of pregnancy; it peaks at term and then decreases over a period of 4 to 6 weeks postpartum |

| Immobility | Includes casts or splints, as well as permanent limb or generalized body immobility, including that from general hospitalization |

| Factor V Leiden mutation | Most common in northern European populations. The heterozygous carrier state exists in 3% to 7% of many samples. A homozygous mutation is less common and confers three times greater risk for VTE relative to the normal genotype. |

| Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome | Very potent risk factor. Associated with large and recurrent PE. May be associated with anticardiolipin antibodies, stroke, myocardial infarction, and frequent first-trimester miscarriages |

| Prothrombin mutation | |

| Hyperhomocysteinemia | Can occur as a result of inadequate folate and B vitamin intake, as well as a genetic mutation in methyltetrahydrofolate reductase. The degree of elevation in risk is controversial |

| Deficient levels of clotting factors | Protein C, protein S, antithrombin III |

| Congestive heart failure | May result from generalized immobility or vascular stasis |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | May result from generalized immobility |

| Air travel | Primary risk with travel in excess of 5000 km (3100 miles) and concurrent other risk factors. The degree of elevation in risk is controversial |

| Obesity | The degree of elevation in risk is controversial |

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Many other diseases may be accompanied by pain, swelling, and tenderness of the leg. Box 71.1 presents a differential diagnosis of conditions that should be considered.

Diagnostic Testing

Pretest Probability

Just like any possible diagnosis in the ED for which further testing is considered, the first step should be an assessment of what the pretest probability of disease is.2,3 This can be done easily by using a clinical decision model such as that derived and validated by Wells et al.4 to stratify patients as low risk or high risk for having DVT (Table 71.2). It has been also advocated by some authors that experienced clinicians may empirically use clinical gestalt to estimate the probability of DVT as low or not low. In either case, documentation on the medical record should clearly indicate the physician’s pretest probability estimate for DVT and what the supporting evidence for this may be from the history and examination.

Table 71.2 Wells Model for Estimating the Pretest Probability for Deep Vein Thrombosis

| CLINICAL VARIABLE | SCORE |

|---|---|

| Active cancer (treatment ongoing, within the previous 6 months, or palliative) | 1 |

| Paralysis, paresis, or recent plaster immobilization of the lower extremities | 1 |

| Bedridden for 3 days or more or surgery requiring general anesthesia in the last 3 mo | 1 |

| Localized tenderness along the deep venous system | 1 |

| Swelling of the entire leg | 1 |

| Calf swelling measured to be 3 cm greater than other leg (at 10 cm below the tibial tuberosity) | 1 |

| Pitting edema in the symptomatic leg | 1 |

| Collateral superficial veins (nonvaricose) | 1 |

| Previous deep vein thrombosis | 1 |

| Alternative diagnosis at least as likely as deep vein thrombosis | −2 |

| A score of 1 or less indicates that deep vein thrombosis is not likely. | |

Adapted from Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Evaluation of D-dimer in the diagnosis of suspected deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1227-35.

Ultrasonography

Venous duplex ultrasonography is noninvasive, not associated with radiation exposure, and accurate in detecting proximal DVT. It has become the first-line imaging test for DVT. When performed by a certified sonographer and interpreted by a radiologist or other credentialed expert, it has a sensitivity and specificity of approximately 95% for proximal thrombosis. Ultrasonography does present some problems, however, including limited availability at night in many institutions, operator variability, occasional difficulty in visualization because of body habitus, and at times interobserver disagreement regarding distal DVT. Nonetheless, it is the imaging test of choice for most ED clinicians, and absence of DVT on ultrasonography should be reassuring that no DVT requiring emergency treatment is present. The question of whether to include visualization of the infrapopliteal veins and the clinical significance of isolated distal DVT are controversial.5,6

Ultrasound Performed by Emergency Department Clinicians

A limited study compared ultrasound of the common femoral and popliteal veins performed by emergency physicians versus formal duplex ultrasound performed by certified ultrasonographers in radiology or vascular departments.7–10 A sensitivity of 89% to 100% and a specificity of 75% to 91.9% were reported. However, the extent of operator training and the specific protocols used have varied widely among published studies.11 One study prospectively investigated the performance of ED-based ultrasound by a heterogeneous mix of 56 emergency physicians with varied levels of ultrasound experience and found a summary sensitivity of 70%, which is low for the evaluation of a disease with significant potential morbidity.11 Not surprisingly, sonographers with the most experience had the most accuracy in this study. It remains to be seen what the best method is to train emergency medicine ultrasonographers for evaluation of DVT and what the overall diagnostic performance would be when done outside academic centers or institutions without ultrasound fellowships and dedicated training. In the future this may be a cost-effective and safe option as this modality evolves. Presently, a clearly negative result of a limited scan performed by a properly trained emergency physician suggests the absence of DVT in the proximal leg veins. If the results are positive or equivocal or involve patients with a high probability, confirmatory studies by the radiology or vascular service should be performed.

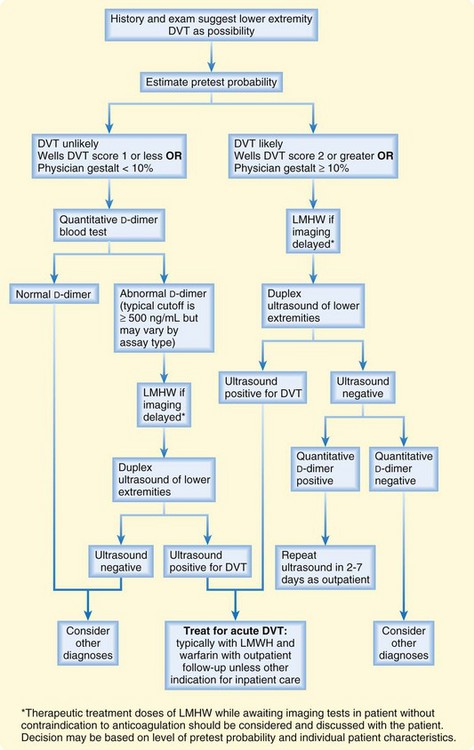

Combining of Pretest Probability, D-Dimer Testing, and Duplex Ultrasonography

This integrated strategy has been advocated as a way to optimize the speed of evaluation, cost, need for imaging, and safety. Similar to the risk stratification and D-dimer approach to PE testing, it starts with physician estimation of the probability of disease in a symptomatic ED patient. If DVT is determined to be “unlikely” by the Wells DVT score (1 or less), a D-dimer test that is negative is reassuring to stop ED testing for DVT and consider other diagnoses.12 If D-dimer is positive, ultrasound is the next step, with results guiding further decision making. One approach for those who are not “DVT unlikely” still uses D-dimer but mandates that all patients, regardless of the D-dimer result, undergo ultrasonography, and D-dimer is then used to guide who needs follow-up in 1 week for an additional ultrasound. This integrated strategy is shown in Figure 71.1.

Treatment

Subcutaneous injection of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH, including enoxaparin, dalteparin, and others) is the standard of care used to treat acute DVT and provide rapid therapeutic anticoagulation until the effects of oral warfarin are sufficient to result in therapeutic anticoagulation (usually 4 to 7 days). The goal of long-term warfarin treatment is to prevent recurrence of DVT or PE, which is achieved by targeting the international normalized ratio (INR) to a level between 2.0 and 3.0 during the treatment period. Therapeutic anticoagulation may also lower the risk for postphlebitic syndrome,13 in addition to the risk for recurrent VTE.

Special Cases Related to Treatment or Disposition Decisions

Isolated Calf Deep Vein Thrombosis

Treatment of isolated calf DVT with anticoagulants is controversial. Advocates of treatment cite the not-insignificant risk for proximal propagation and potential subsequent PE.6 Opponents argue that isolated calf DVT is less likely to be associated with clinically significant PE.5 A period of several days to a week of outpatient treatment with 325 mg of aspirin daily and ultrasound repeated within 1 week may be an option in these patients if discussed with the patient and primary physician.

Postphlebitic Syndrome

Tips and Tricks

Testing for Deep Vein Thrombosis

Physical examination alone is unreliable for the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), but duplex ultrasonography is noninvasive and the diagnostic imaging method of choice.

In patients deemed unlikely to have DVT by a Wells DVT score of 1 or less or an empiric unstructured estimate of the probability of DVT of less than 10%, DVT may be essentially ruled out by a quantitative negative D-dimer blood test.

In patients with DVT deemed to be likely by a Wells DVT score of 2 or greater or an empiric unstructured estimate of probability of greater than 10%, negative findings on duplex ultrasound should be followed by either a negative D-dimer test or a negative additional ultrasound as an outpatient before the diagnosis is excluded.

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

The superficial femoral vein is actually part of the deep venous system, and thrombosis there should be treated as acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

Age is a potent risk factor for DVT, as it is for pulmonary embolism. Although advanced age is not part of the Wells prediction model for DVT, it should be considered when estimating the probability for DVT and the need for imaging.

Patients taking warfarin may still have DVT or extension of DVT despite a therapeutic international normalized ratio.

Do not “rule out” DVT solely on the basis of the absence of risk factors.

The role of emergency department–based ultrasonography is evolving but is operator dependent, and most protocols examine only portions of the proximal deep venous system. Specific training and experience are needed. Caution may be warranted in formulating treatment decisions based on findings that may not have optimal visualization or that may be equivocal.

1 Spencer FA, Lessard D, Emery C, et al. Venous thromboembolism in the outpatient setting. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1471–1475.

2 Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Sackett DL. Users’ guides to the medical literature. III. How to use an article about a diagnostic test. B. What are the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1994;271:703–707.

3 Gallagher EJ. Clinical utility of likelihood ratios. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:391–397.

4 Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Evaluation of D-dimer in the diagnosis of suspected deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1227–1235.

5 Righini M. Is it worth diagnosing and treating distal deep vein thrombosis? No. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(Suppl 1):55–59.

6 Schellong SM. Distal DVT: worth diagnosing? Yes. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(Suppl 1):51–54.

7 Blaivas M, Lambert MJ, Harwood RA, et al. Lower-extremity Doppler for deep venous thrombosis—can emergency physicians be accurate and fast? Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:120–126.

8 Frazee BW, Snoey ER, Levitt A. Emergency department compression ultrasound to diagnose proximal deep vein thrombosis. J Emerg Med. 2001;20:107–112.

9 Jang T, Docherty M, Aubin C, et al. Resident-performed compression ultrasonography for the detection of proximal deep vein thrombosis: fast and accurate. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:319–322.

10 Jolly BT, Massarin E, Pigman EC. Color Doppler ultrasonography by emergency physicians for the diagnosis of acute deep venous thrombosis. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:129–132.

11 Kline JA, O’Malley PM, Tayal VS, et al. Emergency clinician–performed compression ultrasonography for deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremity. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:437–445.

12 Wells PS. Integrated strategies for the diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(Suppl 1):41–50.

13 van Dongen CJJ, Prandoni P, Frulla M, et al. Relation between quality of anticoagulant treatment and the development of the postthrombotic syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:939–942.