Vasopressors

Vasopressors are drugs that produce vasoconstriction and a subsequent increase in systemic vascular resistance (SVR) and mean arterial pressure (MAP). Vasopressors differ from inotropes (see Chapter 87), which primarily produce increased cardiac contractility (inotropy). However, some vasopressors have inotropic properties as well; the predominant effect is usually dose dependent. Vasopressors and inotropes, collectively referred to as vasoactive agents, have been in use since the 1940s, but few controlled trials have assessed their efficacy in improving patient outcomes; their use is largely guided by expert opinion. Vasopressors are used in cardiopulmonary resuscitation, in the treatment of circulatory shock, and in any clinical situation in which the goal is to increase the MAP to restore organ perfusion pressure. In cardiopulmonary resuscitation, vasopressors are used to constrict the peripheral vasculature, preferentially increasing coronary perfusion pressure in an attempt to restore myocardial blood flow, oxygen delivery (![]() ), and the return of spontaneous circulation. In circulatory shock characterized by refractory hypotension, vasopressors are used in a supportive context until definitive therapy can be initiated, with the assumption that clinical recovery will be facilitated by temporarily restoring and maintaining normal organ perfusion pressure. In certain clinical situations (e.g., vasospasm following rupture of a cerebral aneurysm or during cardiopulmonary bypass) vasopressors may be infused continuously to increase MAP to a predetermined level.

), and the return of spontaneous circulation. In circulatory shock characterized by refractory hypotension, vasopressors are used in a supportive context until definitive therapy can be initiated, with the assumption that clinical recovery will be facilitated by temporarily restoring and maintaining normal organ perfusion pressure. In certain clinical situations (e.g., vasospasm following rupture of a cerebral aneurysm or during cardiopulmonary bypass) vasopressors may be infused continuously to increase MAP to a predetermined level.

Physiology

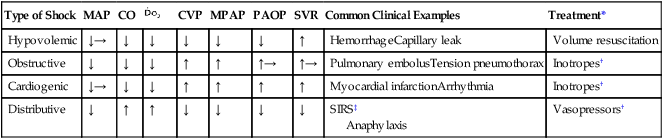

Circulatory shock is typically defined as the presence of profound hypotension such that ![]() is inadequate to meet demand. Depending on the underlying cause, the sympathetic nervous system compensation intended to restore normal organ perfusion pressure is manifested in different ways (Table 88-1). In distributive (i.e., septic) shock, the underlying pathophysiology prevents the compensatory increase in SVR seen in most types of circulatory shock, resulting in refractory hypotension despite a normal or elevated cardiac output (CO) and

is inadequate to meet demand. Depending on the underlying cause, the sympathetic nervous system compensation intended to restore normal organ perfusion pressure is manifested in different ways (Table 88-1). In distributive (i.e., septic) shock, the underlying pathophysiology prevents the compensatory increase in SVR seen in most types of circulatory shock, resulting in refractory hypotension despite a normal or elevated cardiac output (CO) and ![]() . Although the

. Although the ![]() is normal, a MAP below the autoregulatory range (e.g., MAP <65 mm Hg) results in impaired organ blood flow. This occurs because the absolute organ perfusion pressure (or driving pressure) is too low and the normal autoregulatory decrease in organ vascular resistance is insufficient to restore normal organ blood flow. This relationship is expressed by relating Ohm’s law to fluid flow:

is normal, a MAP below the autoregulatory range (e.g., MAP <65 mm Hg) results in impaired organ blood flow. This occurs because the absolute organ perfusion pressure (or driving pressure) is too low and the normal autoregulatory decrease in organ vascular resistance is insufficient to restore normal organ blood flow. This relationship is expressed by relating Ohm’s law to fluid flow:

Table 88-1

Types of Circulatory Shock and Associated Clinical Picture

| Type of Shock | MAP | CO | CVP | MPAP | PAOP | SVR | Common Clinical Examples | Treatment* | |

| Hypovolemic | ↓→ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | HemorrhageCapillary leak | Volume resuscitation |

| Obstructive | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑→ | ↑→ | Pulmonary embolusTension pneumothorax | Inotropes† |

| Cardiogenic | ↓→ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | Myocardial infarctionArrhythmia | Inotropes† |

| Distributive | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | SIRS‡ Anaphylaxis |

Vasopressors† |

*Treatment of the underlying cause of circulatory shock is the primary objective, and pharmacologic therapy with vasopressors, inotropes, or both is used as a temporizing measure to maintain organ perfusion pressure (MAP >65 mm Hg) and CO while the underlying process is corrected.

†Adequate intravascular volume is required, especially with distributive shock, before use of a vasoconstrictor.

< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mml" />

Classification

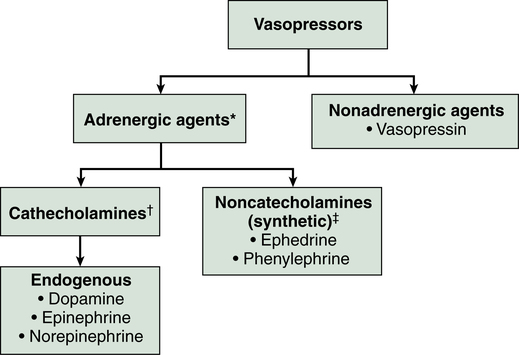

Vasopressor agents are broadly classified here by their clinical effect as either pure vasoconstrictors or inoconstrictors (vasoconstrictors with inotropic properties). Further classification of these agents is illustrated in Figure 88-1, and their standard dosing, receptor binding, and adverse effects are listed in Table 88-2. Although some adrenergic agents stimulate many receptors, producing various cardiovascular effects, their vasopressor actions are mediated via α1-receptors, resulting in arterial and venous vascular smooth muscle contraction and an increase in SVR, pulmonary vascular resistance, and venous return. The only nonadrenergic agent currently in use is vasopressin, which exerts its vasopressor effects through V1-receptor stimulation, resulting in vascular smooth muscle contraction.

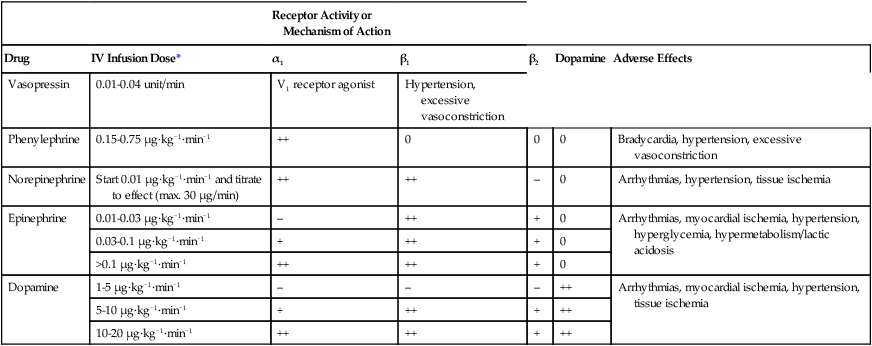

Table 88-2

Standard Dosing of Vasopressors, Their Receptor Binding (or Mechanism of Action), and Adverse Effects

| Receptor Activity or Mechanism of Action | ||||||

| Drug | IV Infusion Dose* | α1 | β1 | β2 | Dopamine | Adverse Effects |

| Vasopressin | 0.01-0.04 unit/min | V1 receptor agonist | Hypertension, excessive vasoconstriction | |||

| Phenylephrine | 0.15-0.75 μg·kg−1·min−1 | ++ | 0 | 0 | 0 | Bradycardia, hypertension, excessive vasoconstriction |

| Norepinephrine | Start 0.01 μg·kg−1·min−1 and titrate to effect (max. 30 μg/min) | ++ | ++ | – | 0 | Arrhythmias, hypertension, tissue ischemia |

| Epinephrine | 0.01-0.03 μg·kg−1·min−1 | – | ++ | + | 0 | Arrhythmias, myocardial ischemia, hypertension, hyperglycemia, hypermetabolism/lactic acidosis |

| 0.03-0.1 μg·kg−1·min−1 | + | ++ | + | 0 | ||

| >0.1 μg·kg−1·min−1 | ++ | ++ | + | 0 | ||

| Dopamine | 1-5 μg·kg−1·min−1 | – | – | – | ++ | Arrhythmias, myocardial ischemia, hypertension, tissue ischemia |

| 5-10 μg·kg−1·min−1 | + | ++ | + | ++ | ||

| 10-20 μg·kg−1·min−1 | ++ | ++ | + | ++ |

*Doses are guidelines, and the actual administered dose should be determined by patient response: ++, potent; +, moderate; −, minimal; 0, none.