19

Vasculitis

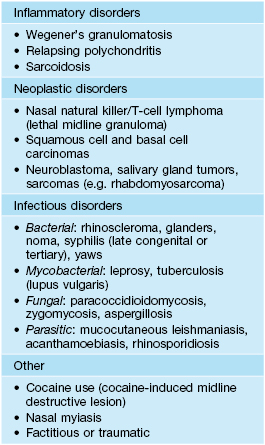

• Cutaneous vasculitides are classified based on the size of the vessels affected, which determines the morphology of the skin lesions (Table 19.1).

Table 19.1

Classification of cutaneous vasculitis.

* Cutaneous involvement is uncommon.

ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies.

• Favors adults but can occur at any age; HSP accounts for the majority of cases in children.

Cutaneous Small Vessel Vasculitis (CSVV)

• The clinical hallmark of CSVV is palpable purpura – nonblanching red-purple papules that favor dependent sites and areas of trauma (Koebner phenomenon) or pressure (e.g. from tight clothing); however, lesions often begin as partially blanching urticarial papules or purpuric macules, and occasionally other morphologies may be observed (e.g. vesicles or pustules; see Table 19.1, Figs. 19.1 and 19.2); frequently asymptomatic but can have associated pruritus, burning, or pain.

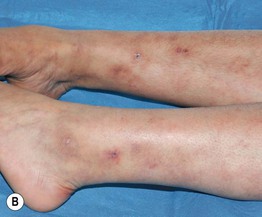

Fig. 19.1 Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. A Classic presentation of purpuric papules on the distal lower extremities; a few lesions have become vesicular. B Early lesions may be pink papules. C Central necrosis with formation of hemorrhagic crusts. A, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD; C, Courtesy, Frank Samarin, MD.

Fig. 19.2 Clinical variants of cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. A Targetoid appearance that can resemble erythema multiforme. B Hemorrhagic crusts in annular configuration. C Predominantly vesicular lesions on the foot. C, Courtesy, Karynne O. Duncan, MD.

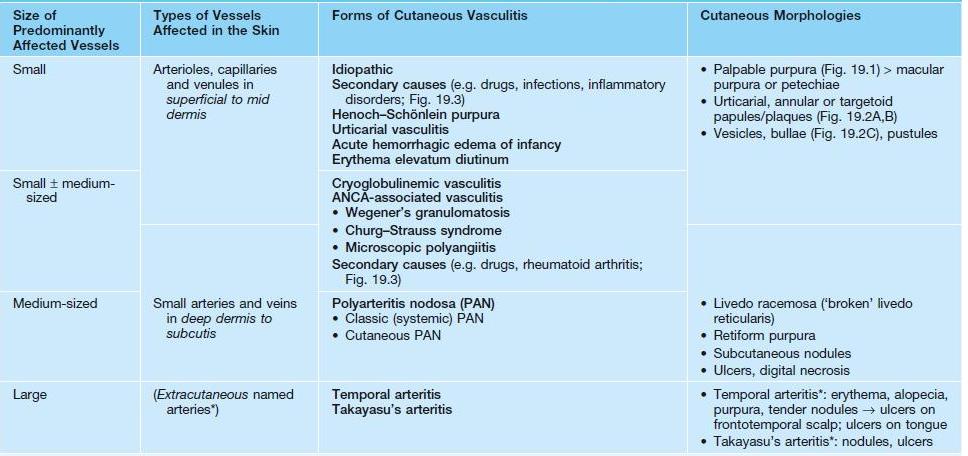

• Possible underlying conditions are presented in Figs. 19.3 and 19.4.

Fig. 19.3 Etiologies of cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. *Often associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA).

Fig. 19.4 Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis associated with systemic disorders. The underlying diseases were Sjögren’s syndrome (A) and rheumatoid arthritis (B). Note the Koebner phenomenon in (A) and the rheumatoid nodules in (B).

• Characterized by the histologic finding of leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) – transmural infiltration of postcapillary venules by neutrophils that undergo fragmentation (leukocytoclasia), leading to fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel walls (see Fig. 1.11).

• DDx: specific CSVV subtypes or systemic vasculitides (see Table 19.1 and below), morbilliform drug eruptions or arthropod bites (with hemorrhage in dependent sites), petechial viral exanthems (see Fig. 68.1), pigmented purpura, erythema multiforme, pityriasis lichenoides, septic emboli.

• Rx: eliminate possible triggers, evaluate for systemic involvement (see Fig. 19.14), and provide supportive care (e.g. leg elevation, NSAIDs); for more severe or persistent (e.g. >4 weeks) skin disease, oral dapsone ± colchicine; if rapidly progressive or ulcerating, a 4- to 6-week course of prednisone may be considered.

Henoch–Schönlein Purpura (HSP)

• Form of CSVV characterized by prominent vascular IgA deposition, which is evident via DIF of a skin biopsy specimen (see Fig. 23.2); favors children <10 years of age, often presenting 1–2 weeks after an upper respiratory tract infection (URI).

• Urticarial papules evolve into palpable purpura, occasionally progressing to bullous or necrotic lesions (Fig. 19.5); typically involves the buttocks and lower extremities, but may be more widespread.

Acute Hemorrhagic Edema of Infancy

• Uncommon CSVV variant that affects children ≤2 years of age, often following a URI.

• Presents with annular or targetoid purpuric plaques and edema favoring the face, ears, and extremities (Fig. 19.6); patients may be febrile, but extracutaneous involvement is rare and spontaneous resolution occurs within 1–3 weeks.

Fig. 19.6 Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Multiple edematous, erythematous plaques on the face and extremities of a toddler. Some of the lesions have begun to become dusky. Courtesy, Ilona J. Frieden, MD.

• DDx: urticaria ‘multiforme’ (giant annular urticaria; see Fig. 3.3), serum sickness-like reaction, urticarial vasculitis, Kawasaki disease, erythema multiforme, Sweet’s syndrome; findings sometimes overlap with HSP.

Urticarial Vasculitis

• Presents with urticarial plaques that have histologic features of LCV (Fig. 19.7); favors middle-aged women, and a hypocomplementemic subset is associated with AI-CTD (especially SLE and Sjögren’s syndrome).

Erythema Elevatum Diutinum

• Presents with persistent violaceous to red-brown plaques on extensor surfaces (e.g. elbows, knees) (Fig. 19.8); patients occasionally have arthralgias or ocular disease, and dapsone therapy is usually effective.

Small and Medium-Sized Vessel Vasculitis

Cryoglobulinemic Vasculitis (See Table 18.3)

• ‘Mixed’ cryoglobulinemia (types II and III) can lead to vasculitis of small ± medium-sized vessels; associated with hepatitis C infection > other infections (e.g. HIV), AI-CTD, and lymphoproliferative disorders.

• Palpable purpura is the most common cutaneous manifestation (Fig. 19.9); other findings can include arthritis/arthralgias, peripheral neuropathy, glomerulonephritis, and hepatitis.

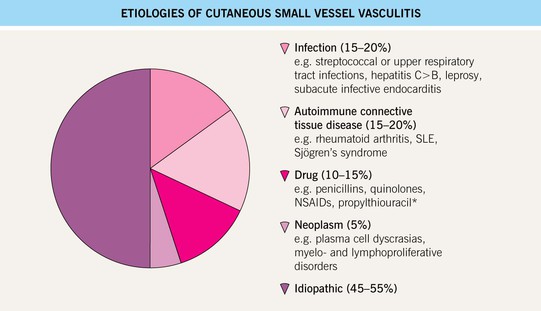

ANCA-Associated Vasculitis

• The features of specific ANCA-associated vasculitides are presented in Table 19.2 and Figs. 19.10–19.12.

Table 19.2

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides.

As in other forms of vasculitis, patients often have constitutional symptoms (e.g. fevers, malaise, weight loss), arthralgias, and arthritis. Diagnostic criteria for each disorder are in italics. Alternative criteria that do not specify a lack of granulomatous inflammation have also been proposed for microscopic polyangiitis.

* Approximately 60% in patients with limited/localized disease.

** Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, which typically presents with umbilicated, crusted papulonodules on extensor surfaces (e.g. elbows) or the face (especially in Wegener’s granulomatosis) (see Chapter 37).

† Evidence via CT represents a diagnostic criterion.

‡ Occasionally triggered by leukotriene inhibitors and/or rapid discontinuation of CS therapy.

§ Usually the initial manifestations.

¶ May be observed in biopsies of the skin, mucosa, respiratory tract, kidney, or nerve.

C-, cytoplasmic ANCA; MPO, myeloperoxidase; PR3, proteinase-3; P-, perinuclear ANCA.

Fig. 19.10 Wegener’s granulomatosis. A Palpable purpura on the distal lower extremity due to small vessel (leukocytoclastic) vasculitis. B Ulceration on the tongue. C Sharply demarcated ulcer on the leg. Such lesions may be misdiagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum. C, Courtesy, Irwin Braverman, MD.

Fig. 19.11 Churg–Strauss syndrome. A Palpable purpura on the buttocks due to small vessel (leukocytoclastic) vasculitis. B Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis presenting with crusted, firm papules on the elbow. C Purpuric dermal plaques on the palm due to vasculitis affecting a small artery (representing a medium-sized vessel). A, C, Courtesy, Kanade Shinkai, MD, and Lindy P. Fox, MD; B, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

Fig. 19.12 Microscopic polyangiitis. A Petechiae and multiple purpuric papules with central necrosis on the plantar surface. B Confluent hemorrhagic plaque on the medial aspect of the foot. Courtesy, Cora Whitney Hannon, MD, and Robert Swerlick, MD.

• Favors middle-aged to older adults, but can occur at any age.

• Requires evaluation for extracutaneous disease (see Fig. 19.14).

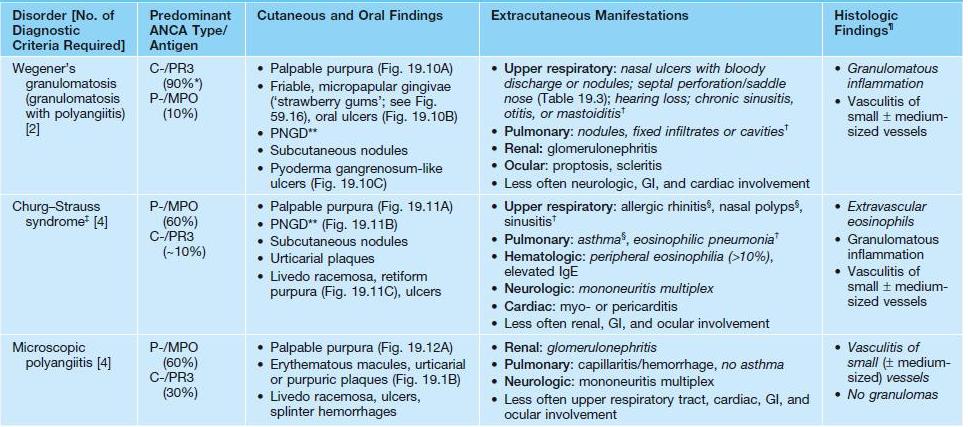

• ANCA against various antigens also occur in other diseases (e.g. ulcerative colitis, autoimmune hepatitis); cocaine use can lead to ANCA (typically against myeloperoxidase, proteinase-3, and neutrophil elastase) together with nasal destruction (Table 19.3) or (with levamisole adulteration) more widespread vasculitis or vasculopathy plus neutropenia (see Fig. 75.3).

Predominantly Medium-Sized Vessel Vasculitis

Polyarteritis Nodosa (PAN): Classic (Systemic) and Cutaneous Variants

• Favors middle-aged adults (men > women), but can occur at any age.

• DDx: other types of vasculitis; livedoid vasculopathy, antiphospholipid syndrome, and other microvascular occlusion syndromes (see Chapter 18); superficial thrombophlebitis, panniculitis.

Classic (Systemic) PAN

• Associated with hepatitis B infection in ~10% of patients.

• Approximately 25% of patients have cutaneous manifestations, including livedo racemosa, retiform purpura, palpable purpura (when small vessels are affected), and ‘punched out’ ulcers > subcutaneous nodules and digital infarcts (Fig. 19.13A).

Fig. 19.13 Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN). A Retiform purpura of the dorsal foot in a patient with systemic PAN. B Livedo reticularis of the lower extremities with multiple small ‘punched-out’ ulcers in an adolescent with cutaneous PAN. This entity can overlap with the PAN-like syndrome with anti-phosphatidylserine–prothrombin complex antibodies that responds to anticoagulation. A, Courtesy, Kanade Shinkai, MD, and Lindy P. Fox, MD; B, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Cutaneous PAN

• Accounts for >30% of childhood PAN and ≤5% of adult PAN.

• May be associated with infections (e.g. streptococcal) or medications (e.g. minocycline – may be P-ANCA+, unlike most forms of PAN).

• Tender subcutaneous nodules favoring the lower extremities, often in a background of livedo racemosa and sometimes following the course of an artery (see Fig. 19.13B); retiform purpura, ulcers, and annular plaques may also be seen.

Diagnostic Approach to Patients with Suspected Cutaneous Vasculitis

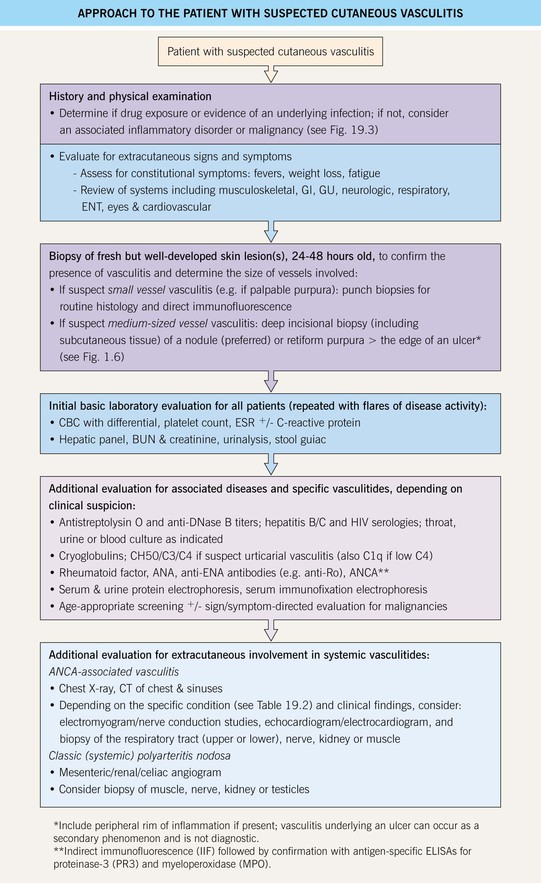

• An approach to the evaluation of patients suspected to have vasculitis, including assessment of underlying conditions and systemic manifestations, is presented in Fig. 19.14.

Fig. 19.14 Approach to the patient with suspected cutaneous vasculitis. AI-CTD, autoimmune connective tissue disease; ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CBC, complete blood count; ENA, extractable nuclear antigen; ENT, ear, nose, and throat; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; GU, genitourinary.

For further information see Ch. 24. From Dermatology, Third Edition.