63 Vascular, Rheumatologic, Functional, and Psychosomatic Back Pain

Clinical Vignette

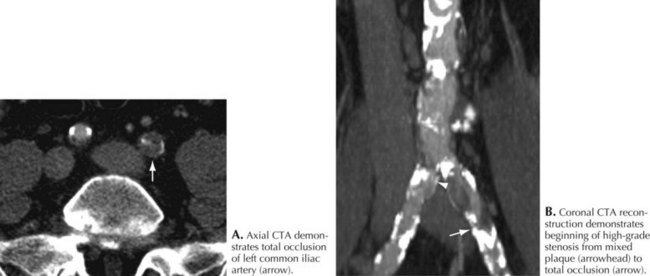

A repeat examination now demonstrated his peripheral pulses were no longer present. He now had a bruit over his left femoral artery CT angiogram demonstrated severe stenosis of the proximal left femoral and iliac artery (Fig. 63-1). Angioplasty and stenting led to immediate pain relief.

Clinical Vignette

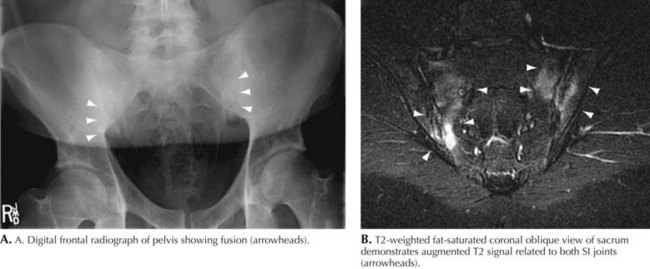

Spinal and hip radiographs demonstrated typical findings of ankylosing spondylitis. These included significant sacroiliac joint sclerosis (Fig. 63-2). A serum HLA-B27 test was positive. A rheumatologist concurred with the diagnosis and began appropriate therapy.

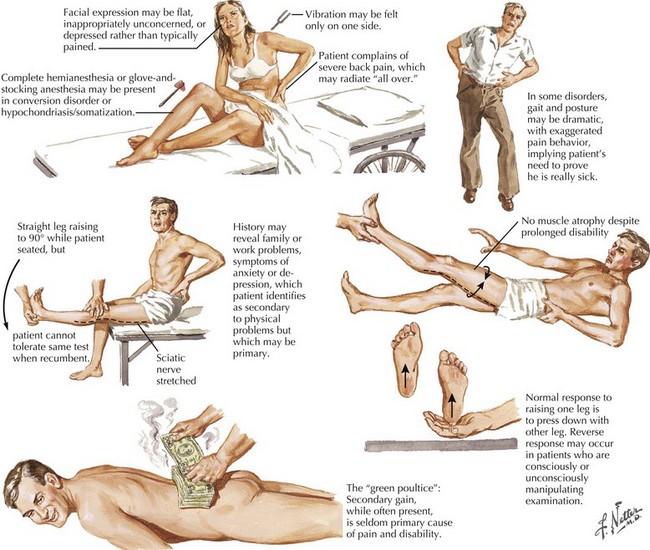

Sincere physicians often encounter difficulties dealing with disingenuous patients seeking a “free ride” or a “green poultice” (Fig. 63-3). Most often secondary gain is the primary motivating factor, particularly with the perspective of a generous workers’ compensation settlement. However, the examining neurologist must carefully evaluate each patient to search for a specific neurologic or other illness, as many patients understandably look for a simple explanation for their troubles—and it is easy to blame the workplace. Often the symptoms become embellished, not uncommonly subconsciously, to prove that a “work-related injury” truly exists. Very often these patients tend to focus on their backs, seeking to prove the presence of a posttraumatic mechanically related disorder. They most definitely want to have their neurologist diagnose a specific work-related neurologic disorder as in the second vignette.

Neurologic Examination

Another example is the well-known observation that when denervation occurs with significant peripheral nerve injury, it is followed by significant muscular atrophy. Such is generally lacking in the nonorganic setting. However, the quadriceps femoris is an exception; it may undergo significant disuse atrophy without a true peripheral nerve injury. Other useful clues and testing modalities can help to verify psychosomatic back pain (see Fig. 63-3).

Treatment

Unfortunately, some individuals with chronic low back pain are subjected to multiple surgeries for less than reasonable indications. Thus they have no chance of improving because no specific lesion such as an extruded disc has been removed. Concomitantly these surgeries, per se, are then utilized to provide justification for granting disability status per se. The patient of course feels “there must have been” an organic work-related etiology for their difficulties if a surgeon “had to operate” on them. Another subset of individuals will continue to complain until a legal settlement is reached. They are identified as having the “green poultice syndrome” (see Fig. 63-3, bottom image). This is of course dependent on gaining a financial settlement; once that is accomplished it is not uncommon to see a rapid resolution of their symptoms and ability to return to their previous activities of daily living!

Hayes J. Psychosomatic back complaints. In: Nervous System. West Caldwell, NJ: Ciba; 1986:198. Jones HR. The Ciba Collection of Medical Illustrations

Henningsen P, Zipfel S, Herzog W. Management of functional somatic syndromes. Lancet. 2007;369:946-955.

Lindstrom-Hazel D. The backpack problem is evident but the solution is less obvious. Work. 2009;32:329-338.

Murphy PL, Volinn E. Is occupational low back pain on the rise? Spine. 1999;24:691-697.

Schultz IZ, Crook JM, Berkowitz J, et al. Biopsychosocial multivariate predictive model of occupational low back disability. Spine. 2002;27:2720-2725.

Storm PB, Chou D, Tamargo RJ. Lumbar spinal stenosis, cauda equina syndrome, and multiple lumbosacral radiculopathies. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am. 2002;13:713-733. ix

Tubach F, Beauté J, Leclerc A. Natural history and prognostic indicators of sciatica. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:174-179.