Chapter 21 Valvular and congenital heart disease

VALVULAR HEART DISEASE

Valvular heart disease is still a common cause for symptoms and disability worldwide. In most economically developed countries the main cause is no longer rheumatic heart disease: congenital valve abnormalities such as mitral valve prolapse and bicuspid aortic valves, degenerative valve disease or infective endocarditis are more common causes.1 However, in many parts of the world, rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease are still major health problems, especially in the young.2,3 Diseases of heart valves produce stenosis, incompetence or both.

RHEUMATIC FEVER

Chronic rheumatic heart disease occurs in about 40% of those with apical and basal diastolic murmurs, and 70% with heart failure or pericarditis during the acute attacks. It is still common in the Middle East, India, Africa and South America, and causes 20–40% of all cardiovascular disease in the Third World.2 It is now rare in North America, western Europe, Australasia and parts of Asia.

MITRAL STENOSIS

Rheumatic fever is the main cause of mitral stenosis; rarer causes are:

Classic signs of mitral stenosis are:

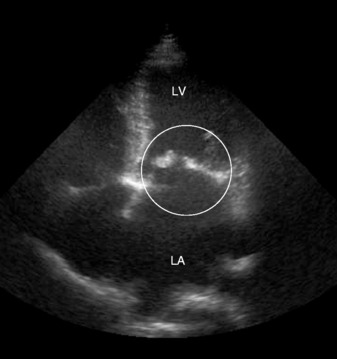

An electrocardiogram (ECG) shows a broad P-wave in lead 2 due to left atrial hypertrophy. Chest X-ray shows an enlarged left atrium and appendage, prominent upper-lobe pulmonary veins, but heart size is usually within normal limits. The diagnosis can readily be confirmed by echocardiography, which allows assessment of the valve anatomy, and estimation of valve area and gradient. Severe stenosis is considered to be present if the valve area is < 1 cm2 (Figure 21.1).

Treatment is the use of β-blockers to slow the heart rate and increase diastolic filling time diuretics, and digoxin is given if the patient is in AF. Anticoagulation is essential if there is significant mitral stenosis and AF. Mitral balloon valvuloplasty has been shown to be very successful therapy with excellent long-term outcome, and compares well with surgical treatment.5 The main contraindications to balloon valvuloplasty are significant mitral regurgitation and heavy calcification when mutual valve replacement should be done.

MITRAL REGURGITATION

There is a considerable difference between acute and chronic mitral regurgitation (Table 21.1). In chronic mitral regurgitation, there is time for the left ventricle and left atrium to adapt to the increasing regurgitation, leading to their gradual enlargement. In acute mitral regurgitation, the sudden pressure overload of the left atrium and pulmonary veins leads to severe pulmonary oedema. The treatment for acute mitral regurgitation is urgent surgery. The management of chronic mitral regurgitation is more difficult. Initially, medical therapy can be helpful, but the probability of postoperative death or persistent severe heart failure after valve replacement increases abruptly when the left ventricular (LV) end-systolic diameter exceeds 45 mm on echocardiography, or ejection fraction falls below 60%.6 In patients without mitral stenosis, mitral valve repair is preferable to replacement, and evidence suggests that preservation of the chordae improves postoperative LV function.7

| Chronic | Acute | |

|---|---|---|

| Causes | Mitral valve prolapse | Ruptured chordae |

| Rheumatic heart disease | Ruptured papillary muscle | |

| LV dilatation (IHD, cardiomyopathies, etc.) | Perforation of leaflet | |

| Prosthetic valves | Prosthetic valves | |

| Physiology | LV volume overload | Sudden pressure overload of LA and pulmonary veins |

| LV dilatation and hypertrophy | ||

| Increased LA size (mean pressure normal initially because of increased compliance) | No change in LV dimension | |

| LA may be normal size | ||

| Symptoms | Asymptomatic initially | Severe dyspnoea |

| Fatigue | ||

| Dyspnoea | ||

| Examination | Pansystolic apical murmur radiating to axilla/lower sternal edge | Harsh pansystolic murmur radiating to axilla and back |

| Third heart sound | Third heart sound | |

| Electrocardiogram | LV hypertrophy | No change (or acute MI) |

| LA hypertrophy | ||

| Chest X-ray | Increased-size LV | Normal LV and LA dimension |

| Increased-size LA | Pulmonary oedema | |

| Echocardiography | Diagnostic | Diagnostic |

| Treatment | Vasodilators and ACE inhibitors (reduce afterload) | Preload and afterload reduction and prepare for urgent surgery |

| Diuretics and digitalis | ||

| Surgery if symptoms and LV size increase (before LV end-systolic diameter > 4.5 cm or LV ejection fraction < 60%) |

MI, myocardial infarction; LV, left ventricle/ventricular; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; IE, infective endocarditis; LA, left atrium/atrial; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme.

MITRAL VALVE PROLAPSE8

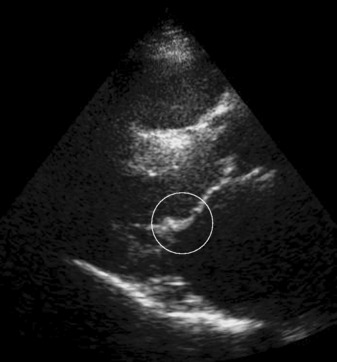

Mitral valve prolapse is usually asymptomatic, but a wide variety of symptoms have been associated, including odd chest pains, palpitations and fatigue. On examination, typical findings are a mid-systolic click and a late systolic murmur, which are separated from the first heart sound, but usually reaching the second heart sound. The murmur may have a crescendo/decrescendo quality. It is usually louder with the Valsalva manoeuvre and on standing. As the prolapse worsens with age the murmur becomes more pansystolic. Echocardiography is diagnostic, and can accurately assess the degree of severity of mitral valve prolapse (Figure 21.2). In most patients, mitral prolapse is a benign condition with a good prognosis. It poses a risk for infective endocarditis, which then leads to a substantial risk of death and need for mitral valve surgery.9 There is a very small increased incidence of embolic neurological ischaemic events.

AORTIC STENOSIS

An ECG confirms LV hypertrophy. The chest X-ray may show:

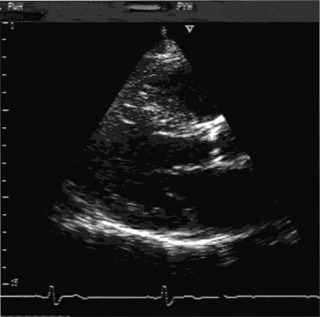

Echocardiography is diagnostic, and allows the measurement of the aortic valve area, gradient and the degree of aortic incompetence (Figure 21.3).

Medical treatment is not effective. Valve replacement should be performed as soon as the patient is symptomatic, if asymptomatic with LV systolic dysfunction, or if the jet velocity is > 4 m/s in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery.10

AORTIC REGURGITATION

The decision to undertake aortic valve replacement in patients with pure aortic regurgitation is difficult. Many patients can survive despite enlarged left ventricles. In general, patients should be advised to have an operation before LV end-systolic dimension exceeds 55 mm or ejection fraction < 60%. Medical therapy with vasodilators such as nefedipine or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors may delay the need for valve replacement.6,11 However, surgery should not be delayed for too long, otherwise irreversible LV dysfunction ensues.

Acute aortic regurgitation is a severe disease with a high mortality, usually due to endocarditis (Staphylococcus or Pneumococcus).12 There is acute LV diastolic pressure and volume overload, which leads to severe pulmonary oedema without LV dilatation. It can be difficult to diagnoseclinically, because the early diastolic murmur is very short and soft. An echocardiogram, however, is completely diagnostic, and can demonstrate severe aortic regurgitation, and, more importantly, early closure of the mitral valve. The treatment is urgent surgery without delay.

TRICUSPID REGURGITATION

Tricuspid regurgitation is usually secondary to right ventricular (RV) dilatation/hypertrophy because of pulmonary hypertension. However, increasingly, infective endocarditis (usually Staphylococcus) in drug addicts is a common cause.13 The diagnosis is made by the presence of large V-waves in the jugular venous pressure, pansystolic murmur at the left sternal edge and echocardiography. Surgery may be necessary if the degree of valvular regurgitation is severe.

INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

This is one of the most important diagnoses not to miss because untreated it is lethal.14,15 A delay in diagnosis considerably lowers the probability of survival. The old adage that ‘fever + murmur = endocarditis’ until proven otherwise remains true. In fact any unexplained illness in a patient with a murmur should raise the question of infective endocarditis. The pattern of infective endocarditis is changing; it may be acquired in the community but increasingly in hospitals particularly as a result of procedures involving vascular catheterization, especially in elderly patients. Prior invasive procedures are more common than dental procedures as a cause. Consequently Staphylococcus aureus is now more common than Streptococcus viridans or enterococci in blood cultures. Infective endocarditis may also affect native valves that were previously thought to be normal and increasingly is a problem associated with intravenous drug abuse.

Clinical features of chronic endocarditis may be misleading. The symptoms are vague ill health, weight loss, malaise with night sweats and mild fever, and many patients are assumed to have influenza. In more chronic cases, there may be nail and conjunctival splinter haemorrhages, clubbing, splenomegaly and anaemia. Regurgitant murmurs (aortic, mitral or tricuspid) are usually present, and heart failure is a bad prognostic sign. Emboli may occur, causing strokes. Cerebral mycotic aneurysms are frequently lethal due to late rupture, which may occur many months after succesful treatment of infective endocarditis (see Appendix).

PROSTHETIC VALVE ENDOCARDITIS (PVE)

The risk of infection is always present. Preventive measures are extremely important in these patients as prosthetic PVE is a cardiological disaster. Even in the best centres, mortality remains high and reoperation is often necessary. The distinction between early infective endocarditis (theatre infection) and late infective endocarditis (community-acquired) is artificial as bacteria acquired in the theatre (such as S. epidermidis) may present many months or even longer after surgery. Since the infection involves the sewing ring, vegetations may not be present but more commonly paraprosthetic leaks or abscesses are found: these usually require transoesophageal echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scanning to visualise.

DIAGNOSIS OF INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

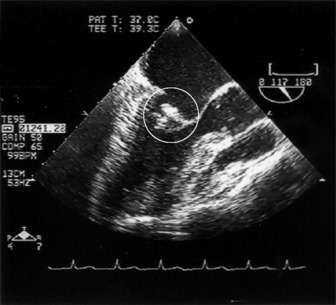

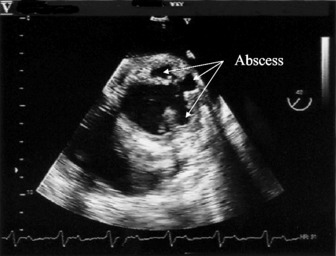

Echocardiography may show vegetations if they are > 3 mm and will give useful information on the degree of regurgitation, any intramyocardial spread (abscess formation) and LV function. Transoesophageal echocardiography is much more useful than transthoracic, particularly for mitral valve endocarditis or PVE and the detection of an abscess (Figure 21.4).16

TREATMENT

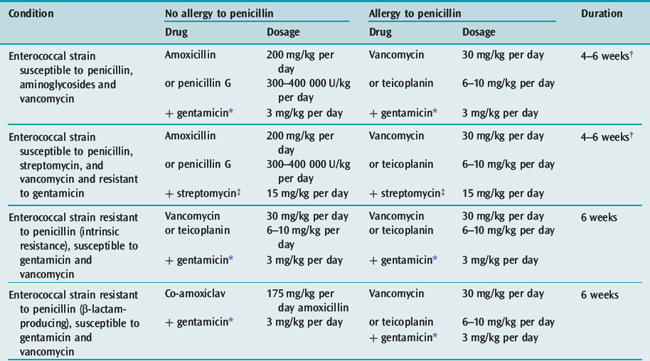

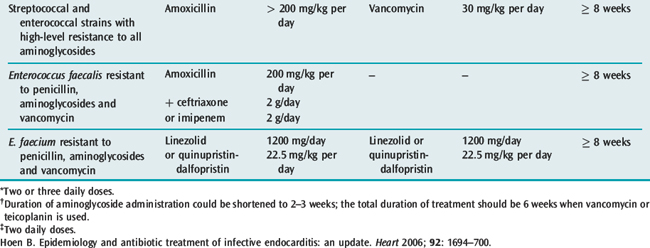

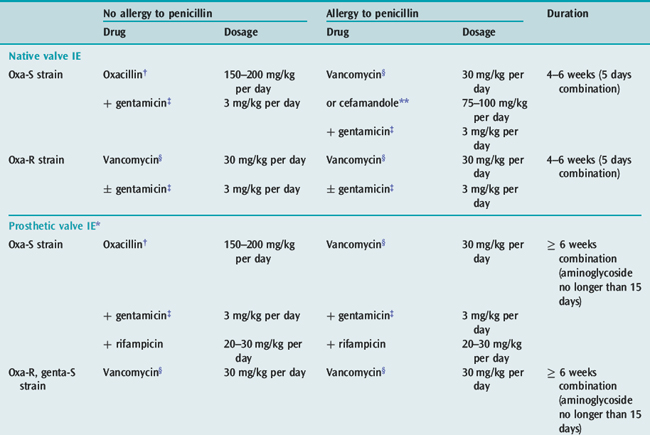

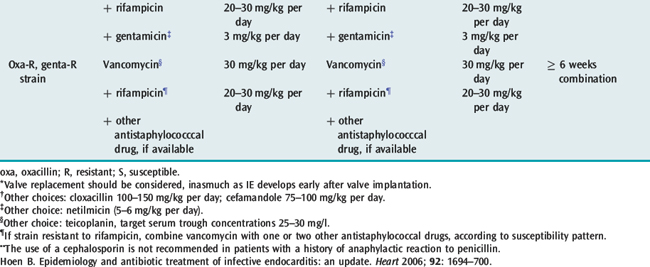

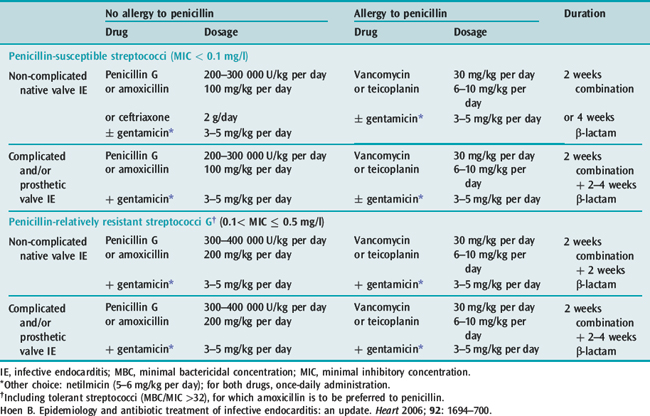

In acute endocarditis treatment should not be delayed while awaiting the results of blood cultures, although this may be acceptable in the patient who has been unwell for weeks or months. There are a number of guidelines for antibiotic treatment which can be consulted17 (for current antibiotic treatment, see Tables 21.2, 21.3 and 21.4). The duration of treatment is traditionally 6 weeks. However, shorter courses with oral therapy have been successfully used for sensitive Streptococcus infections. Treatment of C. burnetii requires treatment for 18 months to 3 years with multiple antibiotics. Current recommendations for prophylaxis can be found in appendix.

Table 21.2 Antibiotic treatment for infective endocarditis caused by penicillin-susceptible (MIC < 0.1 mg/l) or penicillin relatively resistant (0.1 < MIC ≤ 0.5 mg/l) streptococcal endocarditis

PERSISTENT FEVER

A number of possibilities need to be considered, including infection elsewhere either in the heart or outside, such as an infection of a central line which should be removed and sent for culture. Abscesses, paravalvular or intracardiac, are an important cause of persistent or recurrent fever and require surgery. It is nearly always impossible to eradicate an abscess by medical therapy only, and it is generally better to undertake surgery earlier than later. In some patients who appear to be well controlled, an abscess may be detected by transoesophagealechocardiography, but after stopping the antibiotics the infection will recur (Figure 21.5). Extracardiac infection may be due to a myocotic aneurysm which can cause fever or metastatic infection. Myocotic aneurysms of the brain can be a particular problem and may lead to rupture many months or even years later.

CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE IN ADULTS

OSTIUM SECUNDUM ATRIAL SEPTAL DEFECT

Examination typically shows a pulmonary ejection systolic murmur with a wide and fixed second heart sound.

Echocardiography, especially transoesophageal echocardiography, can demonstrate the defect and give an estimate of the pulmonary artery pressure. There is an increased risk of developing Eisenmenger’s syndrome but no risk of endocarditis. Many patients can live to a good age but overall life expectancy is not normal. Closure is by surgery or more usually now an occluder introduced percutaneously is usually recommended if the size of the shunt is > 1.5:1.0. Patent foramen ovale can now also be closed percutaneously. This is often done if there is evidence of paradoxical emboli.18

PATENT DUCTUS ARTERIOSUS

This congenital abnormality is often asymptomatic and survival is usual. At the age of about 20, the risk of infective endocarditis increases, and at the age of about 30, patients with sizeable left-to-right shunts will begin to develop cardiac failure. Patients with significant shunts should havethe patent ductus arteriosus closed by surgery or, increasingly, by transcatheter using an umbrella device.19

FALLOT’S TETRALOGY

This is the cyanotic malformation most frequently associated with survival to adulthood. In these patients, the pulmonary stenosis is usually sufficient to prevent excessive pulmonary blood flow, but not so severe as to causelarge degrees of shunting from the right to the left ventricle. An increasing number of patients who have had complete repair are surviving into adulthood, and overall outcome is excellent.20 The 30-year actuarial survival rate is 90% of the expected, and late health status is very good. However, in some RV fibrosis and damage may lead to ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death. Also there is an increased risk of conduction defects (heart block).

1 Soler-Soler J, Galve E. Worldwide perspective of valve disease. Heart. 2000;83:721-725.

2 Sanderson JE, Woo KS. Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease – declining but not gone. Int J Cardiol. 1994;43:231-232.

3 Eisenberg MJ. Rheumatic heart disease in the developing world: prevalence, prevention, and control. Eur Heart J. 1993;14:122-128.

4 Barlow JB. Aspects of active rheumatic carditis. Aust NZ J Med. 1992;22:592-600.

5 Reyes VP, Raju BS, Wynne J, et al. Percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty compared with open surgical commissurotomy for mitral stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:961-967.

6 Bonow Ro, et alACC/AHA 2006. Guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: Executive Summary. In a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:598-675.

7 Enriquez-Sarano M, Schaff HV, Orszulak TA, et al. Valve repair improves the outcome of surgery for mitral regurgitation: a mutivariate analysis. Circulation. 1995;91:1022-1028.

8 Pellerin D, Brecker S, Veyrat C. Degenerative mitral valve disease with emphasis on mitral valve prolapse. Heart. 2002;88:20-28.

9 Frary W, Devereux RB, Kramer-Fox R, et al. Clinical and health-care cost consequences of infective endocarditis in mitral valve prolapse. Am J Cardiol. 1994;73:263-267.

10 Otto C. Valvular aortic stenosis: disease severity and timing of intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2141-2151.

11 Scognamiglio R, Rahimtoola SH, Fasoli G, et al. Nifedipine in asymptomatic patients with severe aortic regurgitation and normal left ventricular function. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:689-694.

12 Benolti JR. Acute aortic insufficiency. In: Dalen JE, Alpert JS, editors. Valvular Heart Disease. 2nd edn. Boston: Little, Brown; 1987:319-352.

13 Robbins MJ, Sveiro R, Fishman WH, et al. Right-sided valvular endocarditis: etiology, diagnosis and approach to therapy. Am Heart J. 1986;109:558-566.

14 Moreillon P, Que YA. Infective endocarditis. Lancet. 2004;363:39-49.

15 Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, et al. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:633-638.

16 Rinaldi CA, Hall RJ. Echocardiography in endocarditis. In: Izzart MB, Sanderson JE, Sutton MG, editors. Echocardiography in Adult Cardiac Surgery. Oxford: ISIS Medical Media; 1999:155-156.

17 Hoen B. Epidemiology and antibiotic treatment of infective endocarditis: an update. Heart. 2006;92:1694-1700.

18 Meier B. Closure of patent foramen ovale: technique, pitfalls, complications and follow-up. Heart. 2005;91:444-448.

19 Schenek MH, O’Laughlin MP, Rokey R, et al. Transcatheter occlusion of patent ductus arteriosus in adults. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72:591-595.

20 Murphy JG, Gersh BJ, Mair DD, et al. Long-term outcome in patients undergoing surgical repair of tetralogy of Fallot. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:593-599.

APPENDIX

NICE GUIDANCE

Any infection in patients at risk of endocarditis1 should be investigated promptly and treated appropriately to reduce the risk of endocarditis.

If patients at risk of endocarditis1 are undergoing a gastro-intestinal or genito-urinary tract procedure at a site where infection is suspected, they should receive appropriate antibacterial therapy that includes cover against organisms that cause endocarditis.

Patients at risk of endocarditis1 should be: