19

Uterine neoplasia

Introduction

The uterus consists of both the cervix and the body (or ‘corpus’ of the uterus). For many reasons, however, including their causative factors and their treatment, tumours arising from the corpus and the cervix are usually regarded as originating from two separate organs. This chapter will consider cancers arising from the uterine body; cancers arising from the cervix are discussed in Chapter 20.

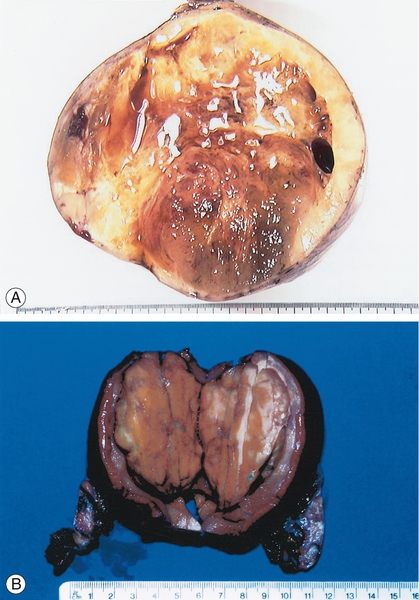

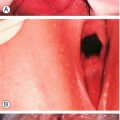

The majority of malignancies arising from the uterine body arise from the endometrium. The endometrium consists of both glandular and supporting (or ‘stromal’) elements and it is possible for either to undergo malignant change. The majority of uterine malignancies are adenocarcinomas arising from the endometrial glands (Figs 19.1 and 19.2A). Sarcomas of the muscle of the uterus, the myometrium or the stromal tissues of the endometrium are much rarer (Fig. 19.2B).

Incidence

In the UK the incidence of endometrial cancer has been increasing and is now the fourth most common cancer in women, after breast, bowel and lung cancers. There are around 7800 cases diagnosed in the UK annually.

Approximately 5% of endometrial carcinomas will develop in women under the age of 40 and 90% will be diagnosed after the menopause. There is evidence that the incidence is rising in developed countries.

Aetiology

The majority of endometrial cancers are associated with conditions in which there are relatively, rather than absolutely, high levels of oestrogen production and it is therefore postulated that oestrogen has a role in the development of the disease (Box 19.1).

High levels of oestrogen may be physiological, as with obesity (due to the aromatization in body fat of peripheral androgens to oestrogens), or with conditions such as polycystic ovarian syndrome (due to long-term anovulation) and late menopause. It is thought that a third of cases are related to obesity. The relationship between diabetes/hypertension and endometrial cancer is probably a result of the increased incidence of obesity in these groups of women. Non-physiological causes of increased oestrogen include unopposed (without progesterone to protect the endometrium) oestrogen hormone replacement therapy (HRT), which increases the risk four-fold. This risk is reduced to a relative risk of < 1.0 with opposed HRT (i.e. with the addition of progestogen for at least 10 days per cycle). Oestrogen-secreting tumours, which are rare, also increase the risk of endometrial carcinoma.

Endometrial cancer is also seen less frequently in women who have used the combined oral contraceptive pill, probably because it administers progestogens throughout the cycle. Women who smoke, and are therefore likely to reach an earlier menopause, also have a lower than expected incidence of the disease.

The more common and oestrogen-dependent type of endometrial cancer is sometimes called type I disease and is seen in women around the time of the menopause or soon after. It is generally diagnosed at an earlier stage and as a result has a better prognosis. There may be premalignant change (see Endometrial hyperplasia, below) and the tumour cells of type I disease usually have oestrogen and progesterone receptors. This form of the cancer has characteristic growth factor alterations, which distinguish it from normal endometrium.

Type II endometrial cancer is probably not related to oestrogen production. It is seen in older women, progresses more rapidly, and is not associated with a hyperplastic or in situ phase. The chances of surviving 5 years with this type of cancer are considerably lower than for the type I form, even with early-stage disease.

Clinical features and diagnosis

Abnormal uterine bleeding is the cardinal symptom of endometrial carcinoma. The bleeding is most commonly postmenopausal, and women with this symptom should be regarded as having malignancy until proven otherwise. Around 5–10% of women with postmenopausal bleeding will have a primary or secondary malignancy, most commonly endometrial cancer (80%), cervical cancer, or (rarely) an ovarian tumour. As the condition can occur in premenopausal women, any irregular uterine bleeding in those over 40 years of age should also be investigated.

A less common mode of presentation in the postmenopausal group is that of vaginal discharge – either blood stained, watery or purulent. Pain is rarely associated with early disease and usually indicates metastatic spread. Endometrial carcinoma can also present with abnormal cells on a smear consistent with endometrial origin.

Mode of spread is principally direct to involve the cervix, through the fallopian tubes and myometrium. Lymphatic and haematogenous spread may also occur.

There are four main methods of investigation as listed below. The method chosen depends on the patient’s risk factors and the local facilities. In current practice, most patients will be investigated through dedicated clinics with pre-defined investigative protocols. In many cases, these clinics will be ‘one-stop’, where all investigations are performed in one sitting.

Ultrasound

Transvaginal scanning can be used to measure the endometrial thickness, and character in postmenopausal women (Fig. 19.3). If the thickness is less than 4 mm and the endometrium smooth and regular, endometrial cancer is very unlikely.

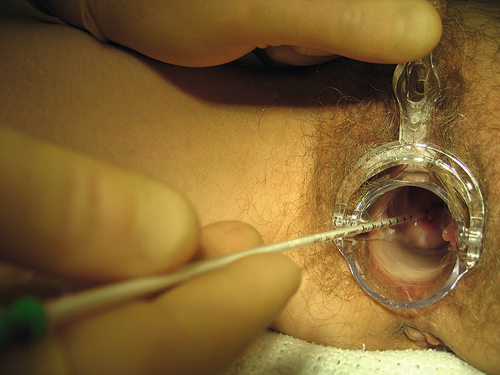

Endometrial biopsy

An outpatient biopsy can be obtained using one of a number of samplers, for example the Pipelle (Fig. 19.4). The Pipelle being a thin (3 mm diameter) plastic tube that is passed through the cervix with a plunger that is withdrawn and sucks a sample of tissue into the tube that can subsequently be analysed histologically.

Dilatation and curettage

This is usually carried out under general anaesthesia. The cervix is dilated sufficiently to allow the introduction of a sharp curette, which is used to sample the endometrium. This used to be standard of care but is now being superseded by less invasive methods. It is rarely used alone now, being combined with hysteroscopy in cases where additional investigations are required.

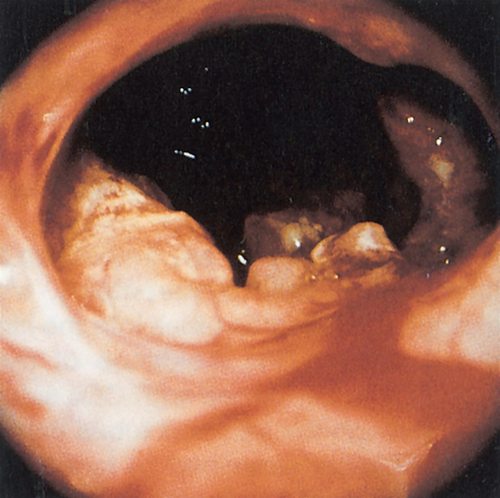

Hysteroscopy

The inside of the uterine cavity can be visualized directly using a hysteroscope (fine telescope), which can be introduced with or without anaesthesia, depending on the instrument and the local facilities (Fig. 19.1). Biopsy or curettage (see above) can also be performed at the same time. Hysteroscopy with biopsy is considered to be the ‘gold standard’ investigation.

Pathology

Endometrial pathology can be divided into hyperplasia, carcinoma or sarcoma.

Endometrial hyperplasia

Prolonged endometrial hyperplasia is a potential risk factor, which is thought to result from persistent and prolonged oestrogenic stimulation of the endometrium. The nomenclature of this condition is confusing and the terms ‘simple hyperplasia’, ‘glandular hyperplasia’, ‘cystic glandular hyperplasia’ and ‘endometrial hyperplasia’ are synonymous. Complex hyperplasia (previously known as ‘adenomatous hyperplasia’) can occur with or without cytological atypia. The atypia may be severe enough to create difficulty in distinguishing the hyperplastic state from a well-differentiated carcinoma.

To diagnose hyperplasia histologically, there should be an increase in the gland-to-stromal ratio. The glands may vary in size and shape or they may branch abnormally. Cytological atypia includes a loss of polarity of cells within the glands, an increase in the nuclear–cytoplasmic ratio, and nuclear irregularity with hyperchromatic changes, chromatin clumping and prominent nucleoli. This atypia is the only feature distinguishing benign endometrial lesions from those with invasive potential.

Simple hyperplasia often occurs in anovulatory teenagers and in the perimenopausal years. Atypical hyperplasia with cytological atypia coexists with endometrial carcinoma in 5–10% of cases, and many will progress to carcinoma. This progression depends on the severity of atypia and it is thought that about 20% will develop carcinoma within 10 years.

Hyperplasia is usually discovered by endometrial biopsy as part of the investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding. It is common to treat hyperplasia with progestogens in young women. The Mirena intrauterine device, which delivers progesterone to the endometrium is often used to manage abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal women and is likely to have a protective effect in those with endometrial hyperplasia. Hysterectomy is the usual recommendation in those with complex atypical hyperplasia with cytological atypia.

Endometrial carcinoma

Endometrial adenocarcinoma can have a variety of histological appearances depending upon whether it is purely glandular, or has areas of squamous differentiation (which may appear malignant or benign) or whether it demonstrates a papillary or clear cell pattern. The latter two forms are associated with a poorer prognosis.

Endometrial sarcoma

Endometrial sarcoma is very rare. It tends to be a locally aggressive tumour that metastasizes early and is generally characterized by a poor prognosis.

Prognostic factors

Endometrial cancer is falsely regarded as a less aggressive tumour than other gynaecological malignancies but this is simply because it more commonly presents at an earlier stage (Table 19.1). Stage for stage, endometrial cancer has a prognosis similar to that of cancer of the cervix. There are many factors that affect the prognosis, the most obvious being the stage of disease. This is an indication of how far the cancer has spread, as well as how aggressive the tumour is. The histological type of endometrial cancer is also important. Papillary serous cancer, which is more common in older women, spreads in a manner similar to cancer of the ovary and, is associated with a significantly poorer prognosis. Other factors which affect the prognosis are outlined in Box 19.2.

Treatment

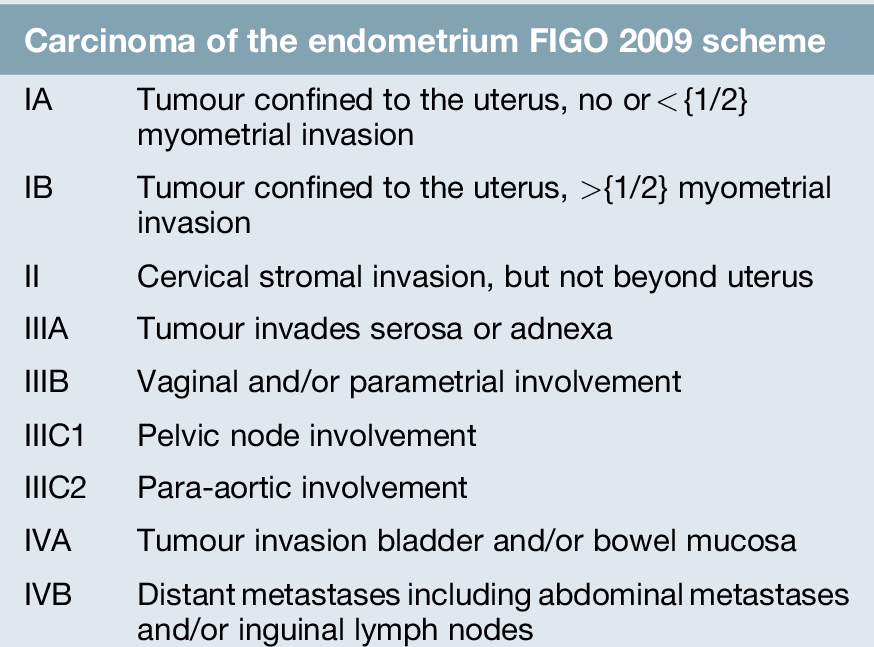

Endometrial carcinoma is staged using the FIGO scheme (Table 19.1). This is a surgico–pathological system, based on the histology results from the excised uterus, tubes, ovaries and lymph nodes and the results of peritoneal cytology. Before operation, however, in addition to the usual preoperative investigations, the patient should have a chest X-ray and liver function tests to look for evidence of metastases.

Other possible preoperative investigations to search for metastases include ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Ultrasound examination can determine the size of the tumour and predict the presence of myometrial invasion. It is also useful in determining the presence of advanced disease. MRI, which is becoming more commonly used, is able to assess the condition of the myometrium more specifically and also to determine the extent of myometrial invasion. More importantly, MRI may be used to determine whether the cervix has been invaded by the tumour (Fig. 19.5). If there is no cervical involvement, a staging laparotomy may be carried out.

The tumour extends into the endocervical canal and is invasive posteriorly at the fundus.

In addition to a hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, there is debate as to whether the pelvic lymph nodes should be removed, sampled or left alone. Any of these strategies is acceptable and none is mandatory. Nevertheless, it would seem sensible to have at least some indication if there is a risk of retroperitoneal disease, although the risk of this can be predicted from other factors such as tumour grade and depth of myometrial invasion. As with any tumour, the more lymph nodes which are removed, the more likely it is that metastases will be found. There are, however, potential complications to lymphadenectomy and the risks of surgery should be weighed against the benefits. If the tumour is of high grade, or there is deep myometrial invasion, extra-pelvic spread is more likely and a surgical assessment of the para-aortic lymph nodes may be appropriate.

If, during the preoperative investigations or at the time of laparotomy, the disease is discovered to have spread beyond the uterus, treatment should be individualized. Treatment of disease in the fallopian tubes or ovaries is with surgery, followed with adjuvant treatment. More widespread tumour, however, should be managed depending on the degree and location of spread and the condition of the patient.

The treatment of those with endometrial cancer after surgery is related to the stage of the disease (Table 19.1). Radiotherapy may be used as adjuvant (postoperative) treatment if the tumour invades the myometrium deeply, as there is a high risk of extrauterine disease. Local radiotherapy to the vault of the vagina (brachytherapy) may prevent recurrence developing in this area. Radiotherapy to the whole pelvis (teletherapy) will also prevent local disease recurring in this area, but, surprisingly, does not improve overall survival. An argument for performing formal lymphadenectomy is that if the nodes are free of tumour, then radiotherapy can be avoided in cases that might otherwise have been irradiated.

Radiotherapy may be used for treatment of local disease if the patient is medically unfit for major surgery. However, this is becoming less common as most patients’ comorbidity can be optimized for surgery. For more advanced lesions, whole pelvic radiotherapy may be used.

If disease is widespread, chemotherapy may be considered. The drugs most helpful in this situation are cisplatinum and doxorubicin. Once again, their influence on survival is controversial, as response rates to measurable disease are only of the order of 20%.

Recurrence

Most relapses occur early (i.e. within 2 years of primary treatment). Recurrences are commonest in the vault of the vagina, but may also be in the lungs, bone, vagina, liver, and inguinal and supraclavicular nodes. It should be remembered that 80% of those with recurrent disease will die within 2 years, and care should be taken to maximize the quality-of-life over this time, rather than subject the patient to treatments with high morbidity and a slim chance of success.

Those with a recurrence who have not received radiotherapy should be considered for this treatment. For the remainder, the choice is between hormonal therapy and chemotherapy. The main hormonal option is high-dose progestogens, which may give a response in around 30% of patients. This aims to slow the progression of the disease. Chemotherapy can produce tumour shrinkage in some cases but toxicity is considerable, not least because these patients are often frail and have severe coexistent medical disorders.

Summary

Endometrial cancer is often considered to be easily treatable, but, stage-for-stage, its survival approximates that of other gynaecological cancers. It is fortunate that most women present with postmenopausal bleeding in the early stages of the disease.

To ensure the best possible outcome, women who present with bleeding 6 months or more after their last menstrual period should be referred urgently for a gynaecological opinion. From there, referral to a cancer centre specializing in the treatment of gynaecological cancer is likely to be beneficial.