14

Urticaria and Angioedema

• Urticaria (hives) is characterized by wheals: evanescent, pale to pink-red, edematous papules or plaques (Fig. 14.1); lesions often have central clearing, a peripheral erythematous flare, and associated pruritus.

Fig. 14.1 Wheals. Wheals can be small or large in size (A) as well as annular or polycyclic (B), but they still retain the classic central pallor and erythematous flare. C Occasionally, more uniform edematous plaques are seen. B, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Individual wheals last <24 hours, which can be documented by outlining them with ink.

• Angioedema represents deeper dermal and subcutaneous or submucosal swelling (Fig. 14.2); affected areas are ill-defined, have minimal or no overlying erythema, and may be painful as well as pruritic.

Fig. 14.2 Angioedema. The swelling is deeper than in wheals and may affect mucosal surfaces. Note the swelling of the lips and periorbital region and the lack of erythema. Courtesy, Clive E. H. Grattan, MD.

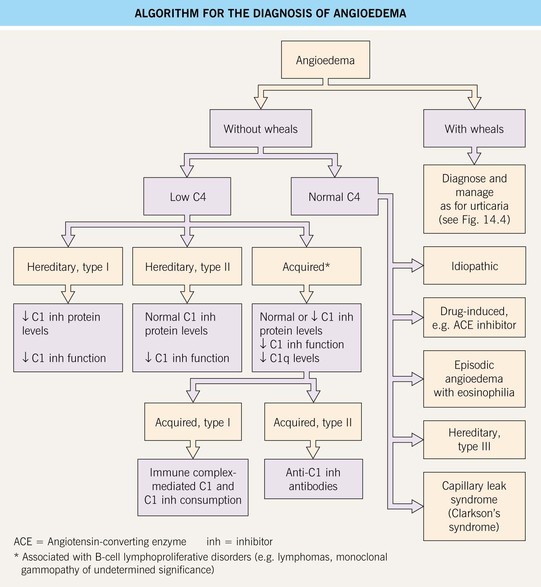

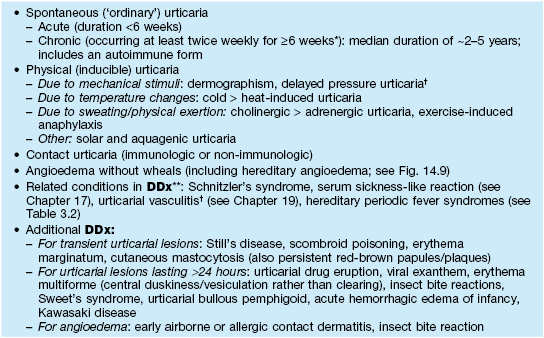

• A classification scheme and DDx for urticaria and angioedema are presented in Table 14.1; patients with angioedema may have associated urticaria, including physical urticaria.

Table 14.1

Classification and differential diagnosis of urticaria and angioedema.

* Urticaria occurring less frequently than this over a long period is referred to as episodic or recurrent.

† Individual lesions tend to last >24 hours; urticarial vasculitis features burning/pain, purpura upon resolution, and a subgroup associated with hypocomplementation and autoimmune connective tissue disease (e.g. SLE).

** Consider for chronic urticaria with associated symptoms such as fevers, pain, and arthralgias.

SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

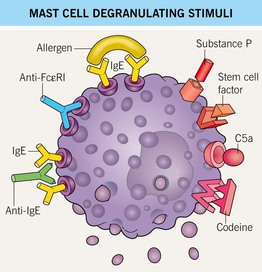

• Stimuli for mast cell degranulation are shown in Fig. 14.3.

Fig. 14.3 Mast cell degranulating stimuli. Both immunologic and non-immunologic stimuli can lead to release of mediators. Stem cell factor is also known as KIT ligand. Autoantibodies against the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI) and the Fc portion of IgE are implicated in chronic autoimmune urticaria.

Spontaneous (‘Ordinary’) Urticaria: Acute and Chronic

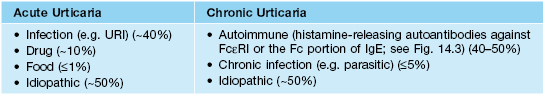

• The most frequent causes of acute and chronic urticaria are listed in Table 14.2.

Table 14.2

Causes of acute and chronic spontaneous urticaria.

FcεRI, high-affinity IgE receptor (present on mast cells); IgE, immunoglobulin E; URI, upper respiratory tract infection.

• Acute urticaria in young children often presents with large annular or polycyclic lesions (urticaria ‘multiforme’; see Figs. 14.1B and 3.3A) that tend to resolve with a transient dusky purplish hue, which can lead to misdiagnosis as erythema multiforme.

• Urticaria can result in sleep disturbances and anxiety.

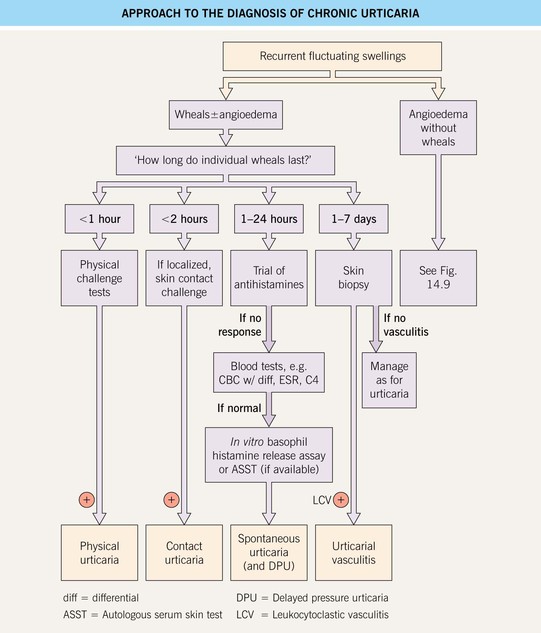

• An approach to the diagnosis of chronic urticaria is outlined in Fig. 14.4; extensive laboratory evaluations (e.g. for food allergies) are extremely low-yield and are not recommended.

Fig. 14.4 Approach to the diagnosis of chronic urticaria. In a positive ASST, a localized wheal and flare response occurs upon intradermal injection of autologous serum, providing evidence of functional histamine-releasing factors in the blood. Regulations regarding blood products limit the availability of this test. Courtesy, Clive E. H. Grattan, MD.

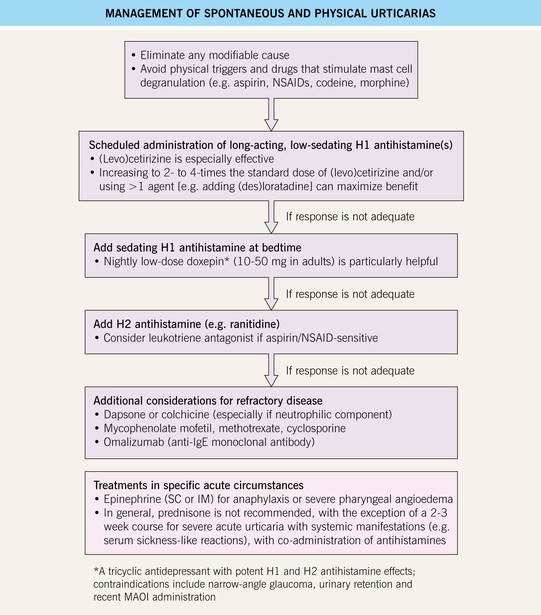

• Rx: a stepwise therapeutic approach is presented in Fig. 14.5; long-acting antihistamines are the mainstay of treatment, and systemic corticosteroids should be avoided.

Physical (Inducible) Urticaria

Dermographism (‘Skin Writing’)

• Affects at least 10% of the general population; may lead to symptoms such as pruritus.

• Linear or irregularly shaped wheals develop at sites of scratching or friction (Fig. 14.6); lesions typically resolve within an hour.

• Can elicit via stroking the skin, e.g. with a thin wooden stick or tongue depressor.

Delayed Pressure Urticaria

• Pruritic and/or painful erythema and swelling (Fig. 14.7) develop 0.5–12 hours after sustained pressure to the skin (e.g. due to tight clothing or shoes); may last several days, sometimes with associated arthralgias and malaise.

Cold Urticaria

• Can elicit via ice cube test (Fig. 14.8; 1- to 10-minute application within glove, then rewarming).

Fig. 14.8 Cold urticaria. Wheals developed on the forearm after placement of an ice cube for 10 minutes, followed by rewarming. Courtesy, Thomas Schwarz, MD.

• Usually primary; <5% of cases are associated with cryoglobulins or cryofibrinogen.

• Rare early-onset variants with autosomal dominant inheritance and a negative ice cube test: cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (see Table 3.2), familial atypical cold urticaria (wheals upon evaporative cooling; PLCG2 mutations).

Contact Urticaria

Schnitzler’s Syndrome

Hereditary Angioedema (HAE)

For further information see Ch. 18. From Dermatology, Third Edition.