Chapter 532 Urinary Tract Infections

Prevalence and Etiology

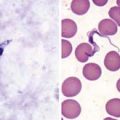

UTIs are caused mainly by colonic bacteria. In girls, 75-90% of all infections are caused by Escherichia coli (Chapter 192), followed by Klebsiella spp and Proteus spp. Some series report that in boys >1 yr of age, Proteus is as common a cause as E. coli; others report a preponderance of gram-positive organisms in boys. Staphylococcus saprophyticus and enterococcus are pathogens in both sexes. Adenovirus and other viral infections also can occur, especially as a cause of cystitis.

Clinical Manifestations and Classification

Clinical Pyelonephritis

Clinical pyelonephritis is characterized by any or all of the following: abdominal, back, or flank pain; fever; malaise; nausea; vomiting; and, occasionally, diarrhea. Fever may be the only manifestation. Newborns can show nonspecific symptoms such as poor feeding, irritability, jaundice, and weight loss. Pyelonephritis is the most common serious bacterial infection in infants <24 mo of age who have fever without an obvious focus (Chapter 170). These symptoms are an indication that there is bacterial involvement of the upper urinary tract. Involvement of the renal parenchyma is termed acute pyelonephritis, whereas if there is no parenchymal involvement, the condition may be termed pyelitis. Acute pyelonephritis can result in renal injury, termed pyelonephritic scarring.

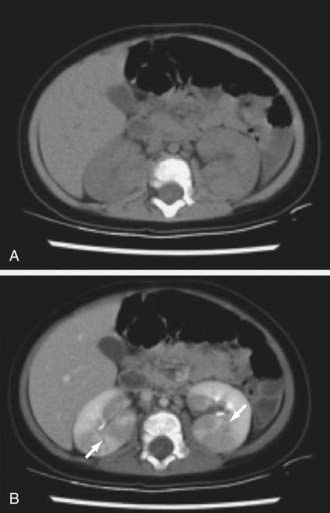

Acute lobar nephronia (acute lobar nephritis) is a renal mass caused by acute focal infection without liquefaction. It may be an early stage in the development of a renal abscess. Manifestations are identical to pyelonephritis; renal imaging demonstrates the abnormality (Fig. 532-1). Renal abscess can occur following a pyelonephritic infection due to the usual uropathogens or may be secondary to a primary bacteremia (S. aureus). Perinephric abscess (see Fig. 532-4) can occur secondary to contiguous infection in the perirenal area (e.g., vertebral osteomyelitis, psoas abscess) or pyelonephritis that dissects to the renal capsule.

Cystitis

Interstitial cystitis is characterized by irritative voiding symptoms such as urgency, frequency, and dysuria, and bladder and pelvic pain relieved by voiding with a negative urine culture. The disorder is most likely to affect adolescent girls and is idiopathic (Chapter 513.1). Diagnosis is made by cystoscopic observation of mucosal ulcers with bladder distention. Treatments have included bladder hydrodistention and laser ablation of ulcerated areas, but no treatment provides sustained relief.

Pathogenesis and Pathology

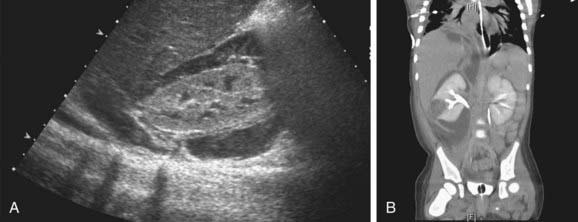

If bacteria ascend from the bladder to the kidney, acute pyelonephritis can occur. Normally the simple and compound papillae in the kidney have an antireflux mechanism that prevents urine in the renal pelvis from entering the collecting tubules. However, some compound papillae, typically in the upper and lower poles of the kidney, allow intrarenal reflux. Infected urine then stimulates an immunologic and inflammatory response. The result can cause renal injury and scarring (Figs. 532-2 and 532-3). Children of any age with a febrile UTI can have acute pyelonephritis and subsequent renal scarring, but the risk is highest in those <2 years of age.

Host risk factors for UTI are listed in Table 532-1. Vesicoureteral reflux is discussed in Chapter 533. If there is grade III, IV, or V vesicoureteral reflux and a febrile UTI, 90% have evidence of acute pyelonephritis on renal scintigraphy or other imaging studies. In girls, UTIs often occur at the onset of toilet training because of voiding dysfunction that occurs at that age. The child is trying to retain urine to stay dry, yet the bladder may have uninhibited contractions forcing urine out. The result may be high-pressure, turbulent urine flow or incomplete bladder emptying, both of which increase the likelihood of bacteriuria. Voiding dysfunction can occur in the toilet-trained child who voids infrequently. Similar problems can arise in school-age children who refuse to use the school bathroom. Obstructive uropathy resulting in hydronephrosis increases the risk of UTI because of urinary stasis. Urethral catheterization for urine output monitoring or during a voiding cystourethrogram or nonsterile catheterization can infect the bladder with a pathogen. Constipation with fecal impaction can increase the risk of UTI because it can cause voiding dysfunction.

Diagnosis

Sterile pyuria (positive leukocytes, negative culture) occurs in partially treated bacterial UTIs, viral infections, renal tuberculosis, renal abscess, UTI in the presence of urinary obstruction, urethritis due to a sexually transmitted infection (STI) (Chapter 114), inflammation near the ureter or bladder (appendicitis, Crohn disease), and interstitial nephritis (eosinophils). Nitrites and leukocyte esterase usually are positive in infected urine. Microscopic hematuria is common in acute cystitis, but microhematuria alone does not suggest UTI. White blood cell casts in the urinary sediment suggest renal involvement, but in practice these are rarely seen. If the child is asymptomatic and the urinalysis result is normal, it is unlikely that there is a UTI. However, if the child is symptomatic, a UTI is possible, even if the urinalysis result is negative.

Treatment

Children with a renal or perirenal abscess or with infection in obstructed urinary tracts can require surgical or percutaneous drainage in addition to antibiotic therapy and other supportive measures (Fig. 532-4). Small abscesses may initially be treated without drainage.

In a child with recurrent UTIs, identification of predisposing factors is beneficial. Many school-aged girls have voiding dysfunction (Chapter 537); treatment of this condition often reduces the likelihood of recurrent UTI. Some children with UTIs void infrequently, and many also have severe constipation (Chapter 298). Counseling of parents and patients to try to establish more normal patterns of voiding and defecation is most important in controlling recurrences. Prophylaxis against reinfection, using TMP-SMX, trimethoprim, or nitrofurantoin at 30% of the normal therapeutic dose once a day, is one approach to this problem. Prophylaxis with amoxicillin or cephalexin can also be effective, but the risk of breakthrough UTI may be higher because bacterial resistance may be induced. There is controversy about prophylaxis against recurrent UTIs in children with low-grade or no reflux because resistant organisms can develop, and the incidence of recurrent infection might not consistently be reduced. Other more high risk conditions for recurrent UTIs that might need long-term prophylaxis include neurogenic bladder, urinary tract stasis and obstruction, reflux, and calculi. There is interest in probiotic therapy, which replaces pathologic urogenital flora, and cranberry juice, which prevents bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation, but these agents have not proved beneficial in preventing UTI in children.

The main consequences of chronic renal damage caused by pyelonephritis are arterial hypertension and end-stage renal insufficiency; when they are found they should be treated appropriately (Chapters 439 and 529).

Imaging Studies

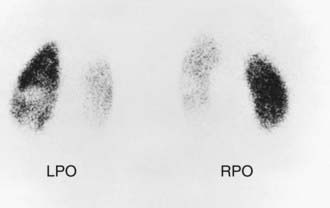

In children with their 1st episode of clinical pyelonephritis—those with a febrile UTI, or, in infants, those with systemic illness—and a positive urine culture, irrespective of temperature, a sonogram of kidneys and bladder should be performed to assess kidney size, detect hydronephrosis and ureteral dilation, identify the duplicated urinary tract, and evaluate bladder anatomy. Next, a DMSA scan is performed to identify whether the child has acute pyelonephritis (Fig. 532-5). If the DMSA scan is positive and shows either acute pyelonephritis or renal scarring, a voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) is performed (Fig. 532-6). If reflux is identified, treatment is based on the perceived long-term risk of the reflux to the child (Chapter 533). One limitation to this approach is that many hospitals caring for children with a febrile UTI might not have facilities for performing a DMSA scan in children. In these cases, a renal sonogram should be performed, and then the clinician needs to decide on whether to send the child to a facility with DMSA capability or instead do a VCUG.

In some centers, the VCUG is delayed for 2-6 wk to allow inflammation in the bladder to resolve; however, the incidence of reflux is identical, regardless of whether the VCUG is obtained acutely at the time of treatment of the UTI or after 6 wk. Obtaining the VCUG before the child is discharged from the hospital is appropriate and ensures that the evaluation is complete. If available, a radionuclide VCUG rather than a contrast VCUG can be used in girls; this technique causes less radiation exposure to the gonads than does the contrast study. However, the radioisotope VCUG does not provide anatomic definition of the bladder, allow precise grading of reflux, demonstrate a paraureteral diverticulum, or show whether reflux is occurring into a duplicated collecting system or an ectopic ureter. In boys, VCUG definition of the urethra is important to detect posterior urethral values (Chapter 534).

Barbosa-Cesnik C, Brown MB, Buxton M, et al. Cranberry juice fails to prevent recurrent urinary tract infection: results from a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:23-30.

Bouissou F, Munzer C, Decramer S, et al. Prospective, randomized trial comparing short and long intravenous antibiotic treatment of acute pyelonephritis in children: dimercaptosuccinic acid scintigraphic evaluation at 9 months. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e553-e560.

Brady PW, Conway PH, Goudie A. Duration of inpatient intravenous antibiotic therapy and treatment failure in infants hospitalized with urinary tract infections. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1-8.

Brady PW, Conway PH, Goudie A. Length of intravenous antibiotic therapy and treatment failure in infants with urinary tract infections. Pediatrics. 2010;126:196-203.

Cheng CH, Tsau YK, Chang CJ, et al. Acute lobar nephroma is associated with a high incidence of renal scarring in childhood urinary tract infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(7):624-628.

Cheng CH, Tsau YK, Kuo CY, et al. Comparison of extended virulence genotypes for bacteria isolated from pediatric patients with urosepsis, acute pyelonephritis, and acute lobar nephroma. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(8):736-740.

Cheng CH, Tsau YK, Lin TY. Is acute lobar nephroma the midpoint in the spectrum of upper urinary tract infections between acute pyelonephritis and renal abscess? J Pediatr. 2010;156:82-86.

Cheng CH, Tsai MH, Su LH, et al. Renal abscess in children: A 10-year clinical and radiologic experience in a tertiary medical center. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:1025-1030.

Cheng CH, Tsau YK, Chen SY, et al. Clinical courses of children with acute lobar nephronia correlated with computed tomographic patterns. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:300-303.

Chevalier I, Benoit G, Gauthier M, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for childhood urinary tract infection: a national survey. J Paediatr Child Health. 2008;44:572-578.

Coulthard MG. Is reflux nephropathy preventable, and will the NICE childhood UTI guidelines help? Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:196-199.

Coulthard MG, Kalra M, Lambert HJ, et al. Redefining urinary tract infections by bacterial colony counts. Pediatrics. 2010;125(2):335-341.

Coulthard MG, Lambert HF, Keir MJ. Do systemic symptoms predict the risk of kidney scarring after urinary tract infection? Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:278-281.

Craig JC, Simpson JM, Williams GJ, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis and recurrent urinary tract infection in children. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1748-1759.

Dai B, Liu Y, Jia J, et al. Long-term antibiotics for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:499-508.

Doré-Bereron MJ, Gauthier M, Chevalier I, et al. Urinary tract infections in 1- to 3-month-old infants: Ambulatory treatment with intravenous antibiotics. Pediatrics. 2009;124:16-22.

Etoubleau C, Reveret M, Brouet D, et al. Moving from bag to catheter for urine collection in non–toilet-trained children suspected of having urinary tract infection: a paired comparison of urine cultures. J Pediatr. 2009;154:803-806.

Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. Executive summary: international clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritic in women: a 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:561-564.

Ismaili K, Lolin K, Damry N, et al. Febrile urinary tract infections in 0- to 3-month-old infants: a prospective follow-up study. J Pediatr. 2011;158:69-72.

Lee MD, Lin CC, Huang FY, et al. Screening young children with a first febrile urinary tract infection for high-grade vesicoureteral reflux with renal ultrasound scanning and technetium-99m-labeled dimercaptosuccinic acid screening. J Pediatr. 2009;154:797-802.

Little P, Merriman R, Turner S, et al. Presentation, pattern, and natural course of severe symptoms, and role of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance among patients presenting with suspected uncomplicated urinary tract infection in primary care: observational study. BMJ. 2010;340:b5633.

Little P, Moore MV, Turner S, et al. Effectiveness of five different approaches in management of urinary tract infection: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c199.

Luk WH, Woo YH, Wai San Au-Yeung A, et al. Imaging in pediatric urinary tract infection: a 9-year local experience. Pediatr Imaging. 2009;192:1253-1260.

Mangin D. Urinary tract infection in primary care. BMJ. 2010;340:c657.

Mantadakis E, Plessa E, Vouloumanou EK, et al. Serum procalcitonin for prediction of renal parenchymal involvement in children with urinary tract infections: a meta-analysis of prospective clinical studies. J Pediatr. 2009;155:875-880.

Masson P, Matheson S, Webster AC, et al. Meta-analyses in prevention and treatment of urinary tract infections. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2009;23:355-385.

Miller DC, Saigal CS, Litwin MS. The demographic burden of urologic diseases in America. Urol Clin North Am. 2009;36:11-27.

Montini G, Rigon L, Zucchetta P, et al. Prophylaxis after first febrile urinary tract infection in children? A multicenter, randomized, controlled, noninferiority trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1064-1071.

Montini G, Zucchetta P, Tomasi L, et al. Value of imaging studies after a first febrile urinary tract infection in young children: data from Italian Renal Infection Study I. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e239-e246.

Mori R, Fitzgerald A, Williams C, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for children at risk of developing urinary tract infection: a systematic review. Acta Paediactria. 2009;98:1781-1786.

Mori R, Lakhanpaul M, Verrier-Jones K. Diagnosis and management of urinary tract infection in children: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2007;335:395-397.

Nguyen HT, Hurwitz RS, DeFoor R, et al. Trimethoprim in vitro antibacterial activity is not increased by adding sulfamethoxazole for pediatric Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. J Urol. 2010;184:305-310.

Olson RP, Harrell LJ, Kaye KS. Antibiotic resistance in urinary isolates of Escherichia coli from college women with urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1285-1286.

Pecile P, Miorin E, Romanello C, et al. Age-related renal parenhchymal lesions in children with first febrile urinary tract infections. Pediatrics. 2009;124:23-29.

Pennesi M, Travan L, Peratoner L, et al. Is antibiotic prophylaxis in children with vesicoureteral reflux effective in preventing pyelonephritis and renal scars? A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1489-e1494.

Preda I, Jodal U, Sixt R, et al. Normal dimercaptosuccinic acid scintigraphy makes voiding cystourethrography unnecessary after urinary tract infection. J Pediatr. 2007;151:581-584.

Roth CC, Hubanks JM, Bright BC, et al. Occurrence of urinary tract infection in children with significant upper urinary tract obstruction. Urology. 2009;73:74-78.

Roussey-Kesler G, Gadjos V, Idres N, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection in children with low grade vesicoureteral reflux: results from a prospective randomized study. J Urol. 2008;179:674-679.

Schnadower D, Kuppermann N, Macias CG, et al. Febrile infants with urinary tract infections at very low risk for adverse events and bacteremia. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1074-1083.

Shah SS, Zoric JJ, Levine DA, et al. Sterile cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis in young children with urinary tract infections. J Pediatr. 2008;153:290-292.

Shaikh N, Ewing AL, Bhatnagar S, et al. Risk of renal scarring in children with a first urinary tract infection: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1084-1091.

Shaikh N, Morone NE, Bost JE, et al. Prevalence of urinary tract infection in childhood: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:302-308.

Siomou E, Vasileios G, Fotopoulos A, et al. Implications of 99mTc-DMSA scintigraphy performed during urinary tract infection in neonates. Pediatrics. 2009;124:881-887.

Tse NK, Yuen SL, Chiu MC, et al. Imaging studies for first urinary tract infection in infants less than 6 months old: can they be more selective? Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24:1699-1703.