Upper extremity blocks

Sandra L. Kopp, MD, Susan M. Moeschler, MD and Denise J. Wedel, MD

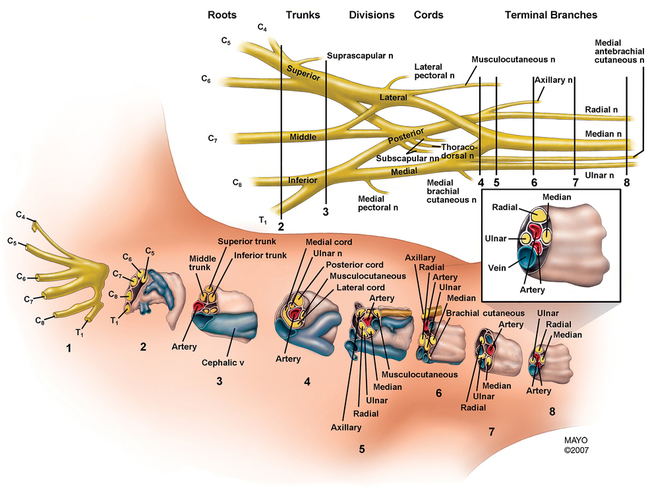

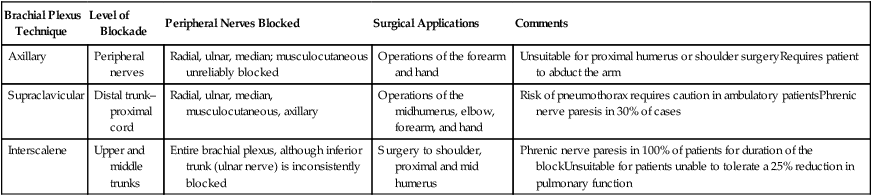

Successful neural blockade of the upper extremity requires extensive anatomic knowledge of the brachial plexus, from its origin as the roots emerge from the intervertebral foramina and of the nerves of the arm and forearm (Figure 127-1). Also important is knowledge of the side effects and complications of peripheral nerve blocks in the upper extremity, as well as the clinical application of available local anesthetic agents for these blocks. Finally, one must not underestimate the role of appropriate sedation during placement of the nerve block and during the surgical procedure (Table 127-1).

Table 127-1

Regional Anesthetic Techniques for Upper Extremity Operations

| Brachial Plexus Technique | Level of Blockade | Peripheral Nerves Blocked | Surgical Applications | Comments |

| Axillary | Peripheral nerves | Radial, ulnar, median; musculocutaneous unreliably blocked | Operations of the forearm and hand | Unsuitable for proximal humerus or shoulder surgeryRequires patient to abduct the arm |

| Supraclavicular | Distal trunk–proximal cord | Radial, ulnar, median, musculocutaneous, axillary | Operations of the midhumerus, elbow, forearm, and hand | Risk of pneumothorax requires caution in ambulatory patientsPhrenic nerve paresis in 30% of cases |

| Interscalene | Upper and middle trunks | Entire brachial plexus, although inferior trunk (ulnar nerve) is inconsistently blocked | Surgery to shoulder, proximal and mid humerus | Phrenic nerve paresis in 100% of patients for duration of the blockUnsuitable for patients unable to tolerate a 25% reduction in pulmonary function |

Adapted from Kopp SL, Horlocker TT. Regional anaesthesia in day-stay and short-stay surgery. Anaesthesia. 2010;65(Suppl 1):84-96.

Interscalene block

Technique

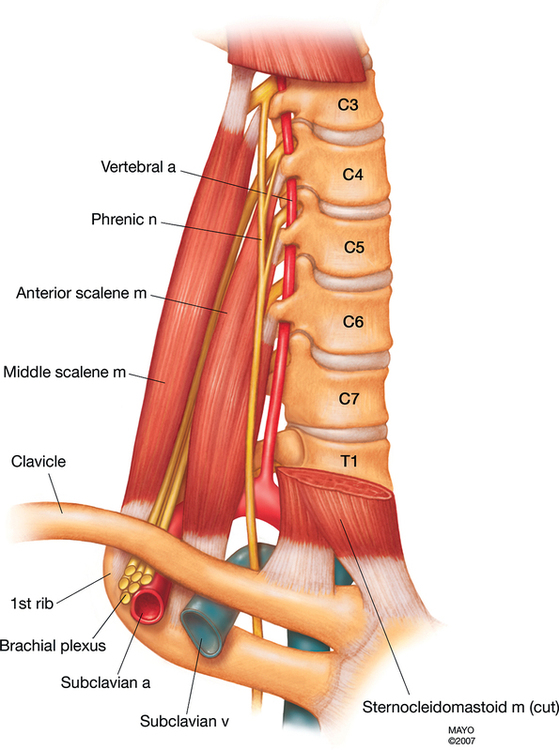

With the patient in the supine position, the patient’s head is turned away from the side to be anesthetized. The lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is palpated and marked; identification of the muscle is facilitated by having the patient briefly lift his or her head. The interscalene groove may be palpated by rolling the fingers posterolaterally from the muscle border, over the belly of the anterior scalene muscle. A line is extended laterally from the cricoid cartilage to intersect the vertical line of the interscalene groove; this represents the level of the C6 transverse process. The external jugular vein often crosses at this level but is not a reliable anatomic landmark (Figure 127-2).

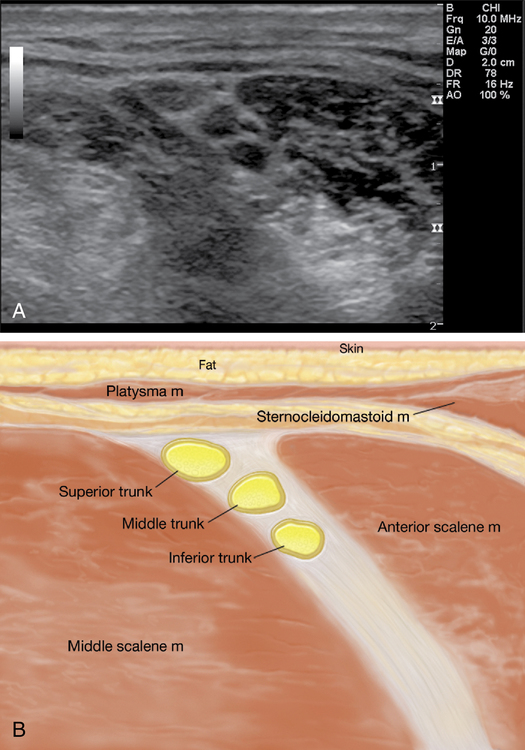

This block is very suited to the use of ultrasound guidance. It is often easiest to obtain a supraclavicular view (see description later) of the subclavian artery and brachial plexus and then trace the plexus up the neck with the ultrasound probe until the plexus trunks are visualized as hypoechoic structures between the anterior and medial scalene muscles (Figure 127-3, A and B). The needle can then be advanced in an out-of-plane or an in-plane approach to a depth of 1 to 3 cm in most patients. After negative aspiration, a test dose is administered to confirm appropriate placement of the needle.

Supraclavicular block

Technique

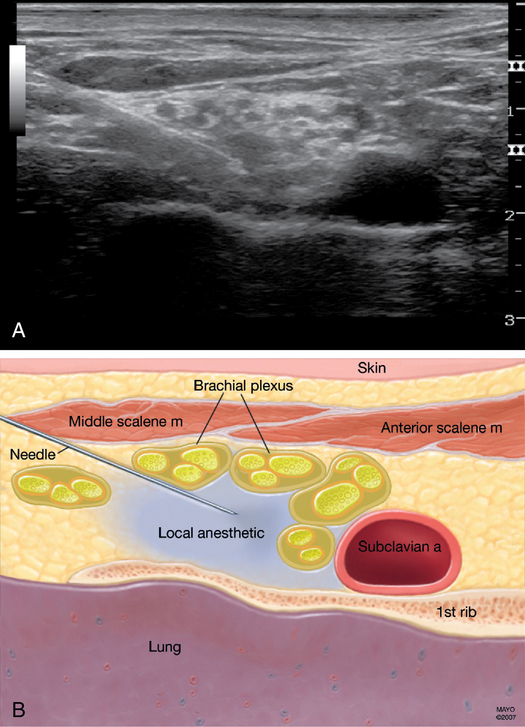

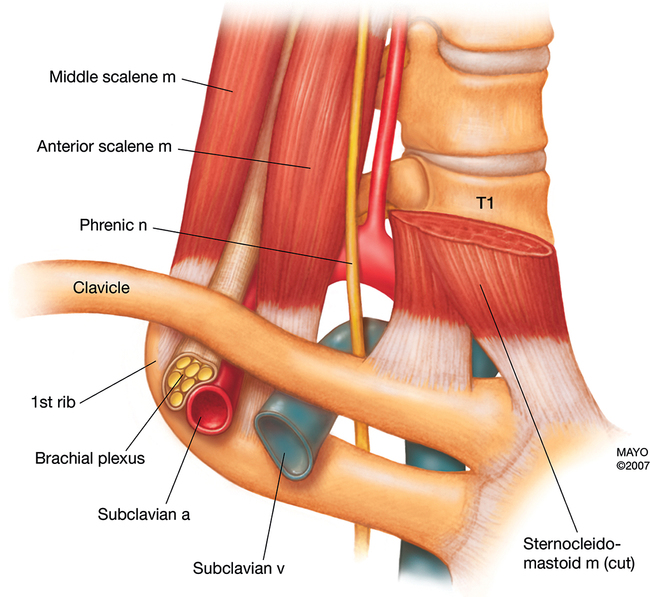

The three trunks of the brachial plexus are compactly arranged cephaloposterior to and surrounding the subclavian artery at the level of the first rib, inferior to the clavicle at approximately its midpoint (Figure 127-4).

The use of ultrasound for the supraclavicular block allows the practitioner to see the brachial plexus structures to be blocked, as well as the subclavian artery and pleura, just below the first rib, which are to be avoided. The patient is positioned as described previously, and the ultrasound probe is placed just cephalad and parallel to the clavicle. The probe is moved medially and laterally until the plexus is viewed just lateral to the subclavian artery. The needle is advanced in plane, lateral to medial, toward the plexus. Following negative aspiration, 20 to 40 mL of local anesthetic agent is injected around the plexus; spread around the neural structures can be seen on the ultrasound (Figure 127-5).

Axillary block

Technique

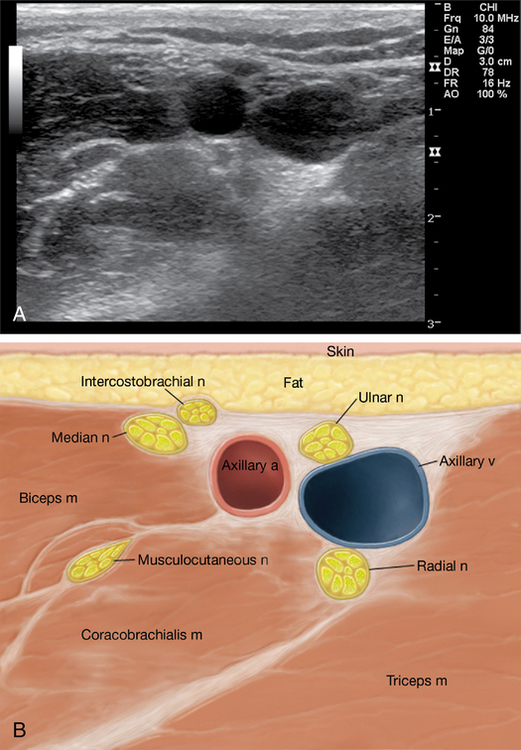

The ultrasound approach to the axillary block involves visualizing the axillary artery and surrounding distinct neural structures at various positions relative to the artery. The block requires several needle redirections to adequately deposit local anesthetic agent around each neural structure. The patient is positioned as described previously. The ultrasound probe is placed just distal and parallel to the axillary crease at a point that best identifies the artery in close proximity to the median, ulnar, and radial nerves (Figure 127-6). The needle is advanced in an in-plane approach to individually block each nerve. Finally, the musculocutaneous nerve can be identified by scanning further laterally within the coracobrachialis muscle. It should be blocked via a separate needle-insertion site.